By Harry C. Boyte

In today’s political climate—dominated by division, privatization of public goods, and deepening distrust—what alternatives do we Americans have? An enduring answer lies in our own civic history: commonwealth politics—a tradition rooted in the idea that citizens are central in caring for the public good, also known as “the commons.”

Defending the Commons: A Republican Stands Up for Public Lands

Ryan Zinke, Republican representative from Montana and former Secretary of the Interior, stripped an amendment from the budget bill that Republican Mark Amodei had advanced putting 500,000 acres of public lands up for sale. Zinke didn’t act out of ideological fealty to either markets or big government. He was rather motivated by his love of the commons.

Calling his stand “my San Juan Hill,” Zinke said, “God isn’t creating more land. Once it’s sold, we’ll never get it back.” His actions halted a sale pushed by fellow Republicans, an inspiring example of how care for public goods can transcend partisanship. As Michelle Nihuis wrote in the New York Times, “America’s public lands – the approximately 600 million acres overseen by the National Parks Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service – are owned by the American people.” The spiritual dimensions and awe-inspiring beauty of public lands are celebrated in the song, “America the Beautiful,” and conveyed in a new documentary about the famous song by filmmaker John de Graaf. There is also another element: public lands are beloved because they represent something everyday citizens have protected and worked for over generations. Far from pristine objects venerated at a distance, public lands have been shaped by We the People. Sometimes citizens work in concert with federal agencies. Sometimes they work independently. In either case, people’s love of public lands is deeply rooted in their own role in shaping them.

Calling his stand “my San Juan Hill,” Zinke said, “God isn’t creating more land. Once it’s sold, we’ll never get it back.” His actions halted a sale pushed by fellow Republicans, an inspiring example of how care for public goods can transcend partisanship. As Michelle Nihuis wrote in the New York Times, “America’s public lands – the approximately 600 million acres overseen by the National Parks Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service – are owned by the American people.” The spiritual dimensions and awe-inspiring beauty of public lands are celebrated in the song, “America the Beautiful,” and conveyed in a new documentary about the famous song by filmmaker John de Graaf. There is also another element: public lands are beloved because they represent something everyday citizens have protected and worked for over generations. Far from pristine objects venerated at a distance, public lands have been shaped by We the People. Sometimes citizens work in concert with federal agencies. Sometimes they work independently. In either case, people’s love of public lands is deeply rooted in their own role in shaping them.

The Legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps

A powerful example of the commonwealth in action was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a New Deal-era program that enrolled more than three million young people from struggling families over its nine-year history. From 1933 to 1942, the CCC planted more than two billion trees, erected 3,470 fire towers, helped to end soil erosion on more than 20 million acres, and built much of the national park system.

Cancelled Stamp From The United States Featuring The Civilian Conservation Corps

The CCC’s impact went beyond physical achievements. As President Franklin Roosevelt anticipated in his message to Congress calling for the CCC in 1933, “More important than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work.”

Education advisors were assigned to each camp. Tens of thousands learned to read and gained high school degrees. Many camps had a citizenship class, tying their work to larger purpose and shaping how participants understood their future jobs.

When Nan Kari and I interviewed CCC veterans for our book, Building America: The Democratic Promise of Public Work, we heard many stories of the CCC’s human impact. “We learned how to work together,” said James Ronning, describing collaboration among those from mountain, urban, and rural backgrounds in his camp. Most impressive were the veterans’ descriptions of the pride, dignity, and sense of public contribution they gained through the work. “We have this park,” Robert Ritchit, told us. “It was a wilderness before and now it’s a nice place to go. I had something to do with that. I was part of the country and of history.” They joined CCC to earn $30 a month, sending most back to their families. Many told us how they also learned they were creating American treasures. Throughout their lives they brought family and friends to see the fruits of their labor.

Camps were segregated, acquiescing to the demands of segregationist senators, but Blacks joined in a higher percentage than whites, and developed skills and confidence to become agents of change. Francis Crowdus, in an African American camp in Corydon, Indiana, was on a baseball team that won the league championship. When the league told them the team couldn’t participate in the final tournament because of segregation, they threatened a boycott of local business. League leaders relented and they went. “We won, and they hired our pitcher,” remembered Crowdus. He also remembers the intellectual energy in his camp. “Everyone would talk about things like politics. We studied history and other broad subjects. If you didn’t know how to read, you’d learn. Everyone had inquisitive minds.”

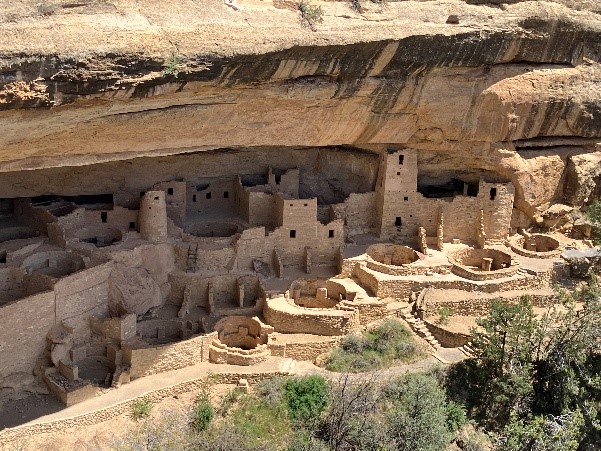

Recently, I took a birthday trip through national parks in Colorado and Arizona. In Colorado, I learned that Mesa Verde National Park, signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, memorializes the history, artistic, architectural talents, and culture of Pueblo tribes. The park also testifies to organizing by local citizens who got the bill through Congress including ranchers like the Wetherill family and leaders of the Women Clubs movement like Virginia McClurg and Lucy Peabody, who founded the Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association. They lobbied effectively, joining with Native leaders in a communications campaign of letter writing, articles, and tours of Mesa Verde for members of the press. It changed the views of people across the region, leading to the park legislation that protected the area from vandalism and looting.

Pueblo cliff dwelling, Mesa Verde

Down the road in Arizona, when I asked the ranger at the welcome center of the Petrified National Park what he thought of the CCC, he responded with enthusiasm. “The CCC guys won the Second World War,” he said. “They learned how to work together across their differences for a big cause. They became citizen soldiers, taking that straight into the war against fascism.” He directed us to the Painted Desert Inn, an old hotel reconstructed by hundreds of CCC enrollees in the 1930s. With help from Pueblo Revival architect Lyle Bennett and Hopi artist Fred Kabotie, the Inn became known for its beautiful decorations. It was a civic commons, a meeting ground for the region and a site for special events. When the National Park Service scheduled its demolition because of cracking walls, the community rallied to save it. The Inn is now a National Historic Landmark.

Hopi art in Painted Desert Inn

Community involvement with the parks continues. The sixty-three designated national parks draw more than 300,000 volunteers each year. Friends of the Petrified Forest Park, for instance, has a mission to “help ensure that the Petrified National Park is preserved as a natural area for education and recreation, to help educate the public about ways to preserve and enjoy the natural beauty of the park, and to help educate the public about the park’s natural and cultural resources.” Tribes and federal agencies signed hundreds of agreements to partner in stewarding public lands.

Reclaiming the Commonwealth Tradition

Framing democracy as a question of voting and delivery of government benefits—rather than empowerment of citizens– is a mistake. As Trygve Throntveit and I observed in a Time magazine article earlier this year, President Jimmy Carter’s shift away from civic populism in 1978 marked a turning point in public policy. His speech promised a government for the people, omitting Lincoln’s full phrase: “of the people, by the people.” The shift was subtle but profound. Loss of the language of active citizenship may well have contributed to Carter’s loss of the election in 1980.

Ironically, in his farewell address, Carter returned to the heart of the matter: “The title of citizen is more important than that of president.” He lived out those words in his post-presidency, committing to efforts which advanced the general welfare around the world.

An expert-knows-best dynamic tied to a marketplace mindset has been at work across all of society, enclosing the commons by privatizing and commodifying public things. Delivery of goods and services for a citizenry of customers and clients has become the progressive paradigm. It devalues citizens and shrinks democracy. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has sought to take the “civil” out of civil service, undermining government workers’ standing and reputation.

The disappearance of citizenship among both Democrats and Republicans is vivid in the language of recent presidential elections. In the 2000 election, George Walker Bush campaigned on a call for civic values. After the election, Bush said in his Inaugural Address, “I ask you to be citizens, not spectators, to serve your nation, beginning with your neighborhood.” Barack Obama also ran his 2008 campaign on a message of citizenship. Announcing his campaign in Springfield, Illinois., on February10, 2007, he said, “This campaign has to be about reclaiming the meaning of citizenship, restoring our sense of common purpose.”

By the Democratic National Convention in the summer of 2024, citizenship had disappeared. The campaign slogan switched from “yes we can” to “yes she can,” a slight of hand by Obama himself. Obama said that democracy must prove it can produce tangible results, but his version of democracy no longer included work of the people. Meanwhile, Donald Trump said he alone could fix our problems.

We urgently need to revitalize the public philosophy of the commonwealth. “Commonwealth” has had several meanings in America, as I have described elsewhere. One is republican or popular government, descended from the English Civil War of the seventeenth century when Parliamentary forces overthrew the king in 1649 and established a Commonwealth. Four states (Massachusetts, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky) officially are Commonwealths.

Commonwealth also meant the civic infrastructure or local commons all depend on. For many immigrants, America represented a chance to recreate commons that had been destroyed or privatized by elites in European societies. Settlers cleared lands and built many kinds of commons: schools, congregations, libraries, meeting halls, roads, and local government itself. In New England many villages are organized around village greens which convey the idea. Such civic labors created “we the people” language of the Preamble to the Constitution, conveying government as the people’s creation.

The country became a theater for self-organizing citizen efforts, which Alexis de Tocqueville described in his classic Democracy in America. David Mathews, former Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) for the Ford administration, recounted such work in the creation of public schools in his book, Reclaiming Public Education by Reclaiming our Democracy. “Nineteenth-century self-rule… was a sweaty, hands-on, problem-solving politics,” Mathews writes. ““The democracy of self-rule was rooted in collective decision making and acting—especially acting. Settlers on the frontier had to be producers, not just consumers. They established the first public schools. Their efforts were examples of ‘public work,’ work done by not just for the public.”

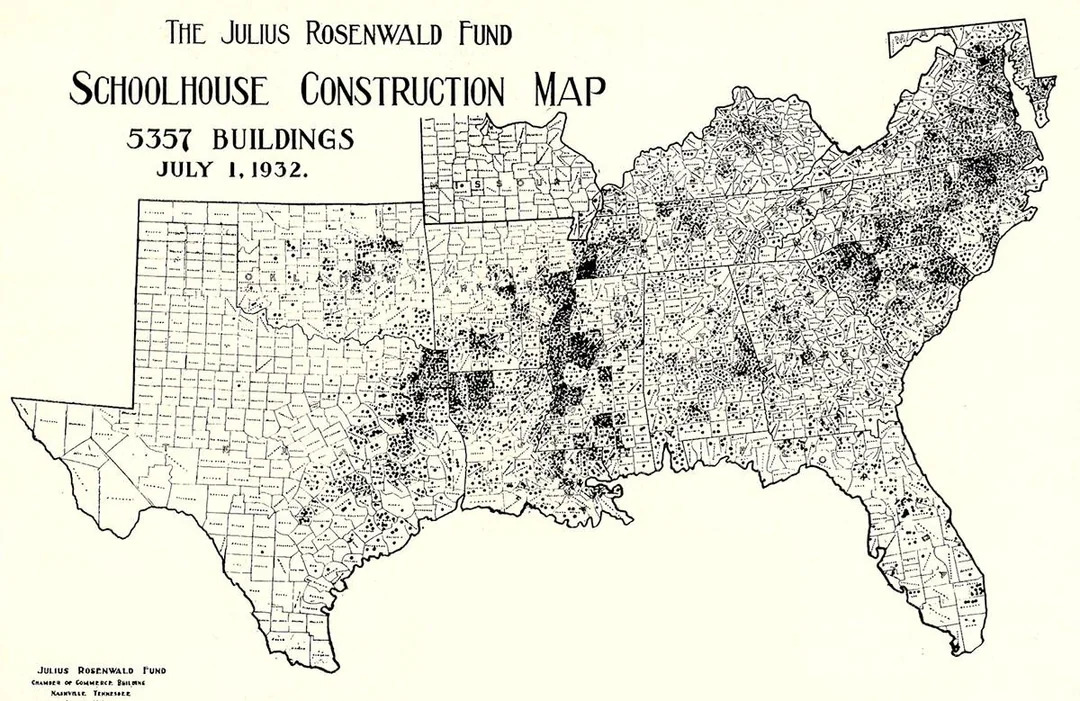

A little-known but remarkable story of the commons are the “Rosenwald” schools and libraries built by Black communities during the era of Jim Crow. A fund that Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, created at Tuskegee provided one-third of the cost of building the schools and libraries. Communities raised the rest from fish fries, church bazaars, sweat equity labor, and winning support from local school boards. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Black communities built more than 5,000 Rosenwald schools and thousands of libraries across the segregated South, which educated one third of all southern Black children until the end of segregation. The schools and libraries were community commons, centers of community life, power, citizen education, and leadership development. John Lewis, Coretta Scott King, Maya Angelou, Medgar Evers, and thousands of local leaders were schooled by the Rosenwald movement.

A little-known but remarkable story of the commons are the “Rosenwald” schools and libraries built by Black communities during the era of Jim Crow. A fund that Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, created at Tuskegee provided one-third of the cost of building the schools and libraries. Communities raised the rest from fish fries, church bazaars, sweat equity labor, and winning support from local school boards. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Black communities built more than 5,000 Rosenwald schools and thousands of libraries across the segregated South, which educated one third of all southern Black children until the end of segregation. The schools and libraries were community commons, centers of community life, power, citizen education, and leadership development. John Lewis, Coretta Scott King, Maya Angelou, Medgar Evers, and thousands of local leaders were schooled by the Rosenwald movement.

In Minnesota, the commonwealth built through citizen labor continued as a public idea through the mid-twentieth century, crossing partisan and economic divisions.

“The Cooperative Commonwealth Program” of the Farmer-Labor Party in 1934 helped elect candidates for governor, the state legislature, Congress, and many local offices. It represented a landmark in civic and economic vision and policy, growing out of farmer, labor, cooperative and educational reform movements. The program contrasted with both state centered policy and unbridled markets, focusing on support for small businesses, cooperatives, and family farms as foundations of civic autonomy and virtue.

The term, commonwealth, was also used by civic and business leaders. Minnesota’s early European American settlers came from New England Yankee backgrounds, where stewardship of the commonwealth was central to the idea of leadership. Bertha Heilbom reported in the St. Paul Pioneer Press issue commemorating statehood. “Those who grew up in Minnesota during the period immediately after the Civil War saw Minnesota emerge from a frontier state and grow into a modern commonwealth.” Leading citizens helped to build libraries and schools, colleges, orchestras, art centers, and theaters beside the growth of business. Until the 1960s, businesses gave back 5 percent of their profits for civic improvement projects. Lotus Coffman, President of the University of Minnesota from 1920 to 1938, titled his inaugural address, “The University and the Commonwealth.”

The Commonwealth Today

More and more people sense that public problems are too complex for government or experts to fix by themselves. The corollary is recognition that self-organized citizen efforts are essential. Braver Angels (BA), the country’s leading organization in addressing the large problem of deepening polarization, illustrates this insight.

BA was founded after the 2016 election with a citizen-centered approach, recognizing that while political and other prominent leaders who espouse a less toxic message are important, “we the people” must drive the process of repairing the sense that Americans are united in a common story and a common project, what can be called America’s narrative commons. BA has developed methods that effectively overcome what is called “affective polarization,” hatred of those with other views. Their workshops have proven highly successful in helping individuals learn to respect others with different opinions and overcome their own stereotypes. The organization has grown to more than 120 local alliances using these methods.

In the summer of 2023, BA described itself as part of a larger movement for civic renewal. A Civic Renewal Support Team was convened by Steve Saltwick, “red” (Republican) cofounder of the BA field operation, and includes prominent Republican leaders like David Eisner, former CEO of AmeriCorps during the Bush administration, as well as Democrats and Independents. Its statement reads in part:

“Braver citizenship is far more than a trip to the ballot box. It is an empowering, self-organizing effort to improve the local community. It strives to include all perspectives of the community. It reflects the traditions and learnings from difficult chapters of the American Experiment – our founding, the Civil War, the civil rights movement, the establishment of equal education opportunities, and much more.”

Braver Angels articulates a language with which to frame citizen-led solutions elsewhere. For instance, hundreds of poor and working-class communities cooperate to create common goods and build civic capacity through the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), the nation’s oldest and largest citizen network, more diverse and institutionally grounded than traditional community organizing.

In their new book, Democracy in Action: Collective Problem Solving in Citizens’ Governance Spaces (Oxford, 2025), Albert Dzur and Carolyn Hendricks identify a distinct kind of civic initiative in which “citizens define the problem and rethink it; develop and experiment with feasible solutions; generate knowledge and networks; and evaluate and refine their approaches.” Unlike social innovations directed by government or seeded by corporations or philanthropies, in citizens’ governance spaces citizens initiated and self-organize, working independently but sometimes in partnership with government, business, and civil society organizations, sometimes on a significant scale.

Such efforts suggest the revival of the civic entrepreneurial spirit which Alexis de Tocqueville found so striking. In some cases, they generate diverse spaces that can be called civic commons.

Repairing the Commons

The US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy in 2023 declared a “national epidemic” of loneliness and social isolation last year, warning that about half of adults experience levels of loneliness which affect physical, mental and social health. One response is a movement to renew local commons as sites for community building and problem solving.

Reimagining the Civic Commons, launched in 2015 by several foundations in partnership with local organizations, identifies urban public spaces that are often overlooked resources, turning them into community assets that promote social trust, bridge socioeconomic divides, and enhance civic life. It defines civic commons broadly, including libraries, parks, trails, community centers, libraries, and public gardens. Beginning in 2015 in Philadelphia, the initiative has taken root in ten major cities, including Detroit, Michigan, and Akron, Ohio, cities historically affected by economic hardship and disinvestment. Its goals include enhanced civic engagement, mixing of diverse demographic groups, environmental sustainability, and creation of new public values. Evaluations included measurable improvements. Twenty percent of visitors volunteered their time to support community activities. Income diversity among visitors increased significantly, with a broader mix of income levels interacting in the civic spaces. Unemployment rates declined, signaling positive economic shifts. In the Fitzgerald neighborhood of Detroit, 93 percent of residents now feel safe during the day—an increase of 13 percent since 2017.

In Minnesota, our Institute for Public Life and Work helped develop the curriculum for a rural-urban exchange sponsored by Civic Bridgers, a service organization formed by Libby Stegger after the election in 2016. Civic Bridgers’ Campus Bridging Initiative immerses students from rural and urban community colleges in two weekends of cross-cultural learning and collaboration. It aims to help rural and urban college students overcome stereotypes, learn about students from different backgrounds, and develop skills of action that bridge divides.

We suggested material about the commonwealth history of Minnesota be added to the curriculum and that it include a “commons” exercise in which students draw maps of commons in their communities.

Student map of local commons in Rochester, Minnesota

In her blog post on the exercise mapping Winona, Minnesota, Angelina Rueda wrote:

“I loved this activity. I imagined the places I frequent in town, where I come together with people, and where I feel community most intensely and as I imagined, my asset map became more and more filled…I snuck a peek at all the other maps around me. Many maps had green spaces, local coffee shops, libraries, and other places that exist in almost every town. Others had completely unique spaces or spaces that expanded my conceptions of what a commons could be. When we began to present our maps, the towns stopped being unfamiliar and I started to recognize how others value their spaces to the same degree.”

The enthusiasm among the students for community commons suggests new forms of service and student community engagement across the country.

Cultural Stirrings

In the spring issue of National Civic Review, Monte Roulier described a public health-related movement spreading across the country. It builds on an empowering civic framework called Vital Conditions, expanding a rich history of public policy supporting capacity-building among “we the people.” Bobby Milstein, a long-time leader in health policy and practice with the group ReThink Health, led a large collaboration of community, civic, religious, and health groups during the first year of COVID, which produced a landmark report, Thriving Together Springboard, which Roulier helped to edit. The report highlights “belonging and civic muscle” as centrally important to community well-being and argues that “stewards in the Thriving Together movement go beyond the limits of a service marketplace… expanding the belonging and civic muscle we need to shape a more vibrant, thriving commonwealth.”

As Roulier puts it, the movement “begins with everyday people and organizations committing to something larger than themselves, acting as stewards of the common good.” He gives several examples that show the receptivity of these ideas and practices. In Northwest Washington, the “Accountability of Health” Network includes 247 partner organizations including eight Tribal Nations.

Signs of change in institutions of higher education also intimate the idea of colleges as commons, retrieving ideas from educational history that stressed local roots and democratic purposes.

Higher education today faces large challenges including a broad assault from the new presidential administration, which is taking advantage of a growing partisan divide and declining public support, as recent polling by Gallup and the Lumina Foundation illustrates:

Confidence has dropped among all key subgroups in the U.S. population over the past two decades, but more so among Republicans. Confidence in higher education among Republicans today is nearly a mirror image of what it was nine years ago. In 2015, 56 percent of Republicans had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence, and 11 percent had little or none. Now, 20 are confident and 50 have little or no confidence.

While colleges have reacted in defensive ways, a longer term view has also emerged in groups like the Institute for Citizens and Scholars, which addresses the lack of what is called “viewpoint diversity.” Thus, for instance, the Black political theorist Danielle Allen has helped to develop a new intellectual framework called pluralism, beyond DEI, which helps students navigate constructively the conflicts that inevitably arise in communities where people have different backgrounds and views. As a recent New Yorker article, “What Comes After DEI,” described, “pluralism demands that conservative evangelicals who don’t believe in same-sex marriage be welcomed to campus alongside gay students, and that political conservatives who oppose affirmative action have fruitful discussions with people of color.”

Calls for pluralism rather than ideological orthodoxy are welcome, but a commonwealth framework adds another dimension that raises questions about what Michael Sandel, a colleague of Allen at Harvard, calls “meritocracy.” Meritocracy is a sorting machine with narrow understandings of excellence. It separates out “winners” from “losers,” “smart” from “stupid,” successful from those left behind, correlating strongly with partisan politics. As Sandel puts it, “Insisting that a college degree is the primary route to a respectable job and a decent life creates a credentialist prejudice that undermines the dignity of work and demeans those who have not been to college.”

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have much to contribute to the conversation about the future of higher education because they include a much broader range of talents and a richer view of knowledge than the present dominant system.

Benjamin Mays, Howard Thurman, Anna Julia Cooper and others were architects of what the historian of Black education Kipton E. Jenson calls “pedagogical personalism.” This educational philosophy “stressed the sacred or otherwise inviolable dignity of persons…[and] promoted an educational process which activated the potential of individuals within and across diverse institutions.” It emphasized “the social benefit of awakening the power of the person’s individual potential… the harmony of means and ends in pursing social justice; and the importance of negotiating through institutions and acting politically for social and structural change.” And it aimed at preparing graduates of HBCUs to be change agents in an unjust and unequal society. As I described last year in my NCR essay, “Return of the Citizen,” nine HBCUs in Texas have recovered and are building on this legacy. Their achievements include an HBCU Caucus in the Texas legislature, with both Democratic and Republican members.

Toward a Future Commonwealth

In all these efforts, we see a renewed civic spirit and sense of shared responsibility for the whole of the American commons: public lands defended, public problems addressed across partisan divides, local civic commons built and rebuilt, institutions reimagined— with the driving force citizens themselves.

We do not need to invent a new tradition or study how to “reach” everyday Americans. We need to remember and revive a tradition with roots which reach back before the Revolution: The American commonwealth. In the commonwealth, democracy is a verb, not only a noun. It is not something done for us or to us, but what we do together.

Harry Boyte, founder, former director and co-director of the Center for Democracy and Citizenship at the University of Minnesota, is Emeritus Senior Scholar in Public Work Philosophy at Augsburg University. As a young man, he was a field secretary for Martin Luther King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.