By Harry C. Boyte

Justice Felix Frankfurter, Supreme Court justice from 1939 to 1962, said that in a democracy “the highest office is the office of citizen.” It has never been more important to remember this role.

This election year is fraught with anxiety and fear about the future. Worry is a global pattern because of the decline in popular belief that political leaders can fix our problems. As the Financial Times recently reported, “Leaders across the developed world have rarely been this unpopular. In the developed world no leader has a rating above fifty percent.” The Times identified trends that feed declining morale such as slow economic growth, increasing inequality, and the feeling that the system is rigged against the average person. Polarization magnifies these trends. I would add others, like meritocratic education, which sorts out “winners” from common folks, and a “cult of the expert,” which exalts efficiency, detaching goals from relational contexts, disempowering everyday citizens, and epidemic loneliness.

At the same time civic ferment with democratic implications and aspirations have been growing. The National Civic League’s “Healthy Democracy Ecosystem” project maps more than 10,000 organizations promoting a healthier democracy. The Inter-Movement Impact Project (IMIP) aims at catalyzing inter-movement collective influence and impact. It sees itself “as strategically connecting pro-democracy leaders, reformers, bridgers, social justice advocates, community organizers, change agents, and constituency groups.”

Such stirrings remain, to date, largely detached from the election debate. I am convinced that this is because of shrunken meanings of democracy. We need a larger story that brings back “the citizen,” in Frankfurter’s foundational sense, recognizing that while government institutions and elections play crucial roles in democracy, they must be complemented by people’s agency and self-organizing public work if we are to animate the democracy ecosystem. This is a narrative that is “federalist,” recognizing the importance of public governance, and also “popular,” a We the People” story of the independent agency and authority of the people. It also involves bridging “civic” structures, policies and civic-minded politicians who connect popular energies to governance.

There is an enormous obstacle: the meaning of “democracy” has shrunk to a narrow focus on elections, a view deeply entrenched in politics, culture, intellectual discussion, and everyday life. In this process, the meaning of citizenship has been reduced to voting or sentimental understandings of volunteering. The civic agency of “the people,” collective capacity for self-organizing to address problems and shape the future, is missing. People feel like bystanders, consumers, clients and spectators of democracy, not as builders and co-creators of a democratic way of life. As Zeynep Tufekci documented in her study of Iowa voters for the New York Times, in turbulent and dangerous times people look for a strongman, not a civic partner. Moreover, as Katie Glueck reported in a NYT piece February 19, 2024, large numbers of citizens feel “burned out,” discouraged, and hopeless.

This thought piece is written for thought leaders, civic entrepreneurs, and organizers in the depolarization group Braver Angels. I argue that to inspire a discouraged citizenry and to renew democratic progress, we need to think about elections not as providing solutions to our problems but as choices among different resources for the whole citizenry. This is a view of government as partner, neither savior nor enemy.

Shrinking democracy

Concepts are power resources in society, shaping the public stories people use to understand the world and their place in it. In his book, Pragmatist Democracy, Christopher Ansell makes the point that while elites skillfully seek to control definitions, they “must contend with audiences who have power to arbitrate the use and meaning of concepts.” Shrinking democracy is in the service of elites, both left and right.

Recent election language illustrates the shrinking.

As the presidential election season heated up in the spring and summer of 2015, Republican and Democratic presidential candidates often talked about democracy. Bernie Sanders, the most progressive candidate in the race, voiced the views of candidates on both sides. “We know what democracy is supposed to be about,” said Sanders. “It is one person, one vote, with every citizen having an equal say.” For all the candidates, the epicenter of politics and democracy’s meaning was elections. Similar views were expressed by Hillary Clinton, George Bush, and Donald Trump.

Such a view reflects conventional wisdom. As the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) puts it: “The United States is a representative democracy. This means that our government is elected by citizens. Here, citizens vote for their government officials. These officials represent the citizens’ ideas and concerns in government.”

Government-centered definitions of democracy and politics inform main currents of academic literature. The influential report of the American Political Science Association’s Task Force on Inequality and American Democracy, chaired by Lawrence Jacobs, a professor at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, included stellar democracy scholars and theorists. Its report, American Democracy in an Age of Rising Inequality, drew stark conclusions about widening inequality and declining public voice in government for middle- and low-income citizens. The report also defined democracy entirely as a constellation of government-centered processes. Its list of “political activities” included “making financial contributions to candidates, working in electoral campaigns, contacting public officials, getting involved in organizations that take political stands, and demonstrating for or against political causes.” It made no reference to the civic culture as the setting of democratic activity. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2020 report, Our Common Purpose, subtitled “reinventing democracy for the 21st century” noted the importance of strengthening associational life. But recommendations for government and election reform make up the great bulk of the report. It neglects workplaces, workers, professions, and institutions such as libraries, schools, businesses, unions, faith communities, nonprofits, colleges, health clinics, museums, sports programs and many others as civic sites and places for developing civic muscle, our capacities for collective action on our challenges.

These views are reflected in the current political and policy debate. The Biden administration’s fact sheet on its infrastructure plan, published March 31, 2021, pledged to “spur the buildout of critical physical, social, and civic infrastructure.” Biden named the stakes he saw a few days earlier. “This is a battle between the utility of democracies in the twenty-first century and [that of] autocracies,” he said. “We’ve got to prove democracy works.” The public works factsheet short reference to “civic infrastructure” was an advance on the rhetoric of 2016 politicians. But mainly the document stressed pledges for government to repair, invest, create, protect, rebuild, modernize, upgrade, revitalize, and train. As Trygve Throntveit and I argued in an essay for the journal Democracy at the beginning of Biden’s administration, the public had disappeared from “public works.”

The president’s State of the Union address on March 7 had allusions to the people in the aftermath of COVID: “In thousands of cities and towns the American people are writing the greatest comeback story never told.” But Biden gave no examples. Instead, the election focuses on what government can do for citizens on the Democratic side. Republicans, line up behind Donald Trump and promise a strong man in a world of chaos. We need to remember the much larger story.

Citizen-centered democracy

The original view of Greeks who invented the word democracy (from the Greek words people and power) focused on popular agency. As the classical scholar Josiah Ober shows in his essay, “The Original Meaning of Democracy,” democracy for the Greeks did not mean voting. It meant, “more capaciously, the empowered demos… not just a matter of control of a public realm but the collective strength and ability to act within that realm and, indeed, to reconstitute the public realm through action.”

In American history, two contrasting meanings of democracy and democratic governance co-existed from the beginning of the United States. One emphasizes politicians and government and the other the agency of the people.

Most founders saw the country as a republic not as an active democracy based on the demos. Thus James Madison in Federalist Papers #10 famously argued that “the delegation of the government [is] to a small number of citizens elected by the rest.” In his view, such a system could “refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations.”

Thomas Jefferson had a different view. “I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of society but the people themselves,” he wrote in a letter to J.C. Jarvis in 1820. “If we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion the remedy is not to take it away from them, but to inform their discretion by education.”

Jefferson may have been aware of the Greek understanding of democracy as popular power, but he drew directly on the work of immigrants who built communities in ways that created a sense of popular agency and authorship. This sense was reflected in the constitutional Preamble. Unlike governments emerging from the distant past or descended from monarchies, the United States’ government was created by “we the people,” a concept closely associated with the term commonwealth, growing from the experience of settlers who built public goods such as congregations, schools, libraries, wells, roads –and local government. As the historians Handlin and Mary Handlin put it in Commonwealth, “For the farmers and seamen, for the fishermen, artisans and new merchants, commonwealth repeated the lessons they knew from the organization of churches and towns . . . the value of common action.”

This culture of civic agency deepened across the country despite the exclusions in the founding sense of “we the people.” In his classic Democracy in America, written in the early 1830s, the French observer Alexis de Tocqueville wrote: “In democratic peoples, associations must take the place of the powerful particular persons.” The people as agents of democratic change continued over the sweep of American history both in the constructive “barn raising” work of building communities, schools, libraries, business associations and cultures and in the great democratic social movements which challenged the exclusions. As the sociologist Robert Bellah put it, “political parties [in America] often come in on the coattails of successful popular movements rather than leading them.” In The Story of American Freedom, Eric Foner shows this dynamic in the 1930s. “It was the Popular Front, not the mainstream Democratic Party, that forthrightly sought to popularize the idea that the country’s strength lay in diversity and tolerance, a love of equality, and a rejection of ethnic prejudice and class privilege.”

The civil rights movement demonstrated how people and government both had distinctive and necessary roles in dismantling the legal system of segregation. Building on a remarkable and largely unknown history of democratic citizenship in communities over many decades, the civil rights movement activated millions of people. In the process government was a necessary but often shaky ally. President Lyndon Johnson made crucial differences, helping shape the public narrative, making federal appointments, protecting civil rights workers and championing legislation like the public accommodations bill of 1964 and voting rights in 1965. But most civil rights leaders saw government as an instrument of the people, not as a solution or savior. Bayard Rustin, brilliant organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, understood this particularly well. When the White House extended an offer for the president to speak, he argued with others that the March should not be co-opted by the Kennedy administration. The March needed to be the expression of the people themselves.

The “organizing wing” of the movement – Septima Clark, Ella Baker, Myles Horton, Dorothy Cotton and others – all saw democracy as a living concept and practice. Clark, an architect of the movement’s citizenship schools whom Martin Luther King called “the mother of the movement,” articulated their purpose in this way: “To broaden the scope of democracy to include everyone and deepen the concept to include every relationship.” Vincent Harding, a great public intellectual in the movement and sometime speechwriter for King, argued similarly. “The civil rights movement was in fact a powerful outcropping of the continuing struggle for the expansion of democracy in the United States,” he wrote. “It demonstrates…the deep yearning for a democratic experience that is far more than periodic voting.” The nonviolent philosophy of the movement played a crucial role in the people-centered view of democracy. It created a sense of equality, dignity, citizenship, and “somebodiness” among Blacks that inspired the whole country and rippled around the world.

In recent years, a shrunken view of democracy as a democratic republic has become conventional wisdom, while the views of those like pragmatists William James and John Dewey, settlement house leaders like Jane Addams, and Black philosophers of education, culture and the civil rights movement like Alaine Locke, James Weldon Johnson, W.E.B. DuBois, Benjamin Mayes, Howard Thurman, Anna Cooper, Septima Clark, Ella Baker, Martin Luther King and many others who saw democracy as an empowering way of life have been forgotten. It is time to remember.

Democratic stirrings

In the broad, diverse civic ferment of the present moment, there are examples of efforts that clearly build on and revitalize the tradition of citizen-centered problem solving. Here are three:

Black Education

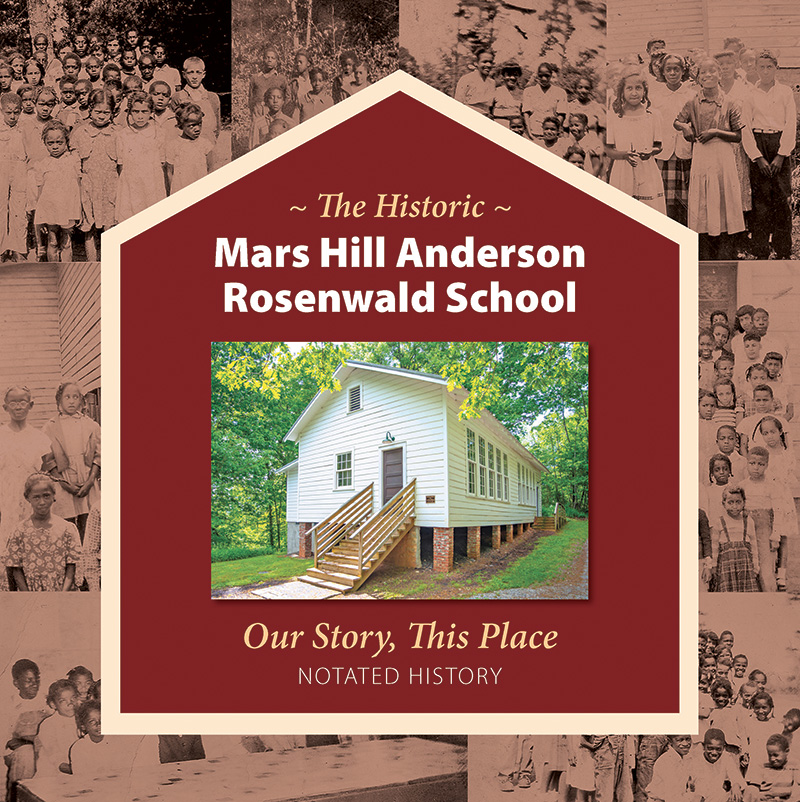

In an essay in the new publication of the University of Texas, Freedom Schools: A Journal of Democracy and Community, I tell the story of thousands of “Rosenwald” schools and libraries built by Black communities during the era of Jim Crow and their close ties to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). They were centers of community life, civic leadership and hope. John Lewis, Coretta King, Medgar Evers, Maya Angelou, Bobby Austin, Eugene Robinson, and thousands of local leaders were schooled by the Rosenwald movement. A network of Black teachers called “Jeanes teachers,” educated at HBCUs, did most of the organizing of communities to build the schools. In Hope and Healing: Black Colleges and the Future of American Democracy, former Morehouse president John Silvanus Wilson, Jr. shows how HBCUs have led the rest of higher education in civic education.

The citizenship focus of the Rosenwald movement and HBCUs fed into the hundreds of adult education citizenship schools sponsored by SCLC’s Citizenship Education Program (CEP), where I worked. From 1961 to 1968, local folks were trained at Dorchester Center, returned to their communities, and created citizenship schools in Rosenwald sites, beauty parlors, libraries, churches and elsewhere. Participants learned how to organize voter registration drives and also how to better their communities. Dorothy Cotton, director of CEP, described the philosophy: “We intended to establish and deepen the concept and awareness of ourselves as citizens. I would always say, ‘You will discover your capacity and your obligation to help solve the problems we face in communities, as a people, as a society. If things are going to change, you will have to change them.’” They were what historian Sara Evans and I call “free spaces”: sites where people learn active democracy as a way of life and hone civic skills to cross bitter divisions.

Such understandings of democracy and citizenship are reappearing in an alliance of Texas HBCUs called “Democracy Schools.” Black students of Robert Ceresa, director of the Politics Lab at the Janes Farmer House at Huston-Tillotson University in Austin, have provided much of the organizing and energy for the alliance, which is working with the cross-partisan community organizing group Central Texas Interfaith. The University of Texas Press’ new journal Freedom Schools surfaces the civic heritage of Black education and describes and analyzes current expressions. The Austin Public Libraries have invited a partnership to help make this history visible and also to shape libraries as vital civic sites in communities. Organizers seek to deepen the democratic mission and practice democratic work. The rationale for support of HBCUs in Texas, developed for the third annual conference of the alliance, explicitly makes the point: “[Our] practice reclaims and revives democracy and citizenship defined as “We the People,” the uniquely American story, practice, and ideal of democracy as the work of everyone, not simply politicians and government.” At the third annual Democracy Schools conference meeting at St. Philips College in San Antonio, state legislators announced a HBCU legislative caucus to advance such aims.

Braver Angels

Braver Angels is another example of citizen-centered democracy, a leading organization in addressing the problem of deepening polarization. It was founded after the 2016 election with a citizen-centered approach, recognizing that while political leaders who espouse a less toxic message are crucial partners, “we the people” have to drive the process, with the understanding that depolarization is a necessary condition for a “return of the citizen.” The second national BA convention in 2019 expressed this view. The platform declared BA’s aim “to renew our trust in one another and build our civic muscle,” and to strive for “’the beloved community’ of Dr. Martin Luther King…and ‘the more perfect Union’ of the Founders.” In 2020, Braver Angels joined with a group of former congressional members in a series of webinars with politicians from both parties, to advance the possibility for a cross-partisan public problem solving with civic dimensions. In 2023, two leaders of the group, Dennis Ross, a former Republican congressman from the 10th district of Florida, and Donna Edwards, a former Democratic congresswoman from Maryland, participated in a Former Members of Congress webinar on the Rosenwald legacy. Edwards told stories of her mother and aunt, who went to Rosenwald schools in North Carolina.

Braver Angels is another example of citizen-centered democracy, a leading organization in addressing the problem of deepening polarization. It was founded after the 2016 election with a citizen-centered approach, recognizing that while political leaders who espouse a less toxic message are crucial partners, “we the people” have to drive the process, with the understanding that depolarization is a necessary condition for a “return of the citizen.” The second national BA convention in 2019 expressed this view. The platform declared BA’s aim “to renew our trust in one another and build our civic muscle,” and to strive for “’the beloved community’ of Dr. Martin Luther King…and ‘the more perfect Union’ of the Founders.” In 2020, Braver Angels joined with a group of former congressional members in a series of webinars with politicians from both parties, to advance the possibility for a cross-partisan public problem solving with civic dimensions. In 2023, two leaders of the group, Dennis Ross, a former Republican congressman from the 10th district of Florida, and Donna Edwards, a former Democratic congresswoman from Maryland, participated in a Former Members of Congress webinar on the Rosenwald legacy. Edwards told stories of her mother and aunt, who went to Rosenwald schools in North Carolina.

BA has developed a variety of methods that effectively overcome what is called “affective polarization,” hatred of those with other views. Their workshops are successful in helping individuals learn to respect others with different views and overcome their own stereotypes. In its convention in the summer of 2023, BA described itself as part of a larger movement for civic renewal. Local BA Alliances are starting to develop civic skills and the entrepreneurial spirit to better whole communities through cross-partisan action. As Steve Saltwick, “red” (Republican) cofounder of the BA field operation and its first Senior Fellow, puts it, “Civic Renewal empowers the nation to restore ‘the office of the citizen’ as the highest office in our American democracy.” He tells a recent story to make the point”

BA has developed a variety of methods that effectively overcome what is called “affective polarization,” hatred of those with other views. Their workshops are successful in helping individuals learn to respect others with different views and overcome their own stereotypes. In its convention in the summer of 2023, BA described itself as part of a larger movement for civic renewal. Local BA Alliances are starting to develop civic skills and the entrepreneurial spirit to better whole communities through cross-partisan action. As Steve Saltwick, “red” (Republican) cofounder of the BA field operation and its first Senior Fellow, puts it, “Civic Renewal empowers the nation to restore ‘the office of the citizen’ as the highest office in our American democracy.” He tells a recent story to make the point”

The town of Newfield, New York, had argued about whether to put a stop sign and crosswalk on Main Street for years. There were arguments – many heated – about the sign. It seemed that there was no solution – until the citizens of the town used their skills and techniques of Braver Angels to depolarize first. Then they captured diverse perspectives on the crosswalk in a Town Hall. They decided to build the crosswalk. The citizens took action. Most agreed – the citizens had made their community better.

For Saltwick, the crosswalk is “democracy in action.”

Civic Governance

In the health field a new and empowering civic framework in government called Vital Conditions is emerging to build on and expand examples of policy and government action supporting community capacity building among “we the people.” Bobby Milstein, a long-time leader in health policy and practice, led a large collaboration of community, civic, and health groups during the first year of COVID, which produced a landmark report, Springboard: to Thriving Communities. It highlights “belonging” and “civic muscle” as centrally important to community well-being and has led to wide ferment in federal agencies and policies concerned with community well-being. In this approach, government shifts from savior or enemy to partner and resource. As Rachel Levine, Assistant Secretary for Health, put it in her keynote address to the American Public Health Association annual meeting last November:

“The vital conditions framework identifies the core elements needed to create a thriving community rather than…descriptions of vulnerabilities or negative determinants in a community. This work asks us to make philosophical shifts in how we work and what we are trying to realize…”

Levine proposes that the new initiative, People and Places Thriving, “provides shared concepts and language through which the federal government can better engage civil society.” It likely has generated resources for the comeback stories that Biden referenced in his State of the Union.

Such examples renew traditions of catalytic governance with roots in the New Deal and earlier. They are also theorized by the new transdisciplinary field of “Civic Studies,” whose core concepts are agency and the citizen as co-creator of communities. The late Elinor Ostrom, one of the co-founders, won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for her research which showed that common pool resources, the commonwealth, is best sustained when created and taken care of through relatively independent community action. Her Nobel Prize Economics lecture in 2009 was “Beyond Markets and States.”

What is democracy? What kind of politics advances it? And where are the public-minded citizens we urgently need and how are they developed?

These are crucial questions for wide discussion this year and Braver Angels is ideally suited to take leadership in the process.

Harry Boyte was founder, director, and co-director of the Center for Democracy and Citizenship at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey Institute (now school) of Public Affairs and is now Senior Scholar in Public Work with the Institute for Public Life and Work. He coordinated the cross partisan “Reinventing Citizenship” initiative which worked with the White House Domestic Policy Council from 1993 to 1995 and co-chaired the civic policy subcommittee of the Obama 2008 campaign. Boyte is founder of Public Achievement, an international youth civic education initiative and co-founder of Civic Studies. As a young man he was a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.