By Nick Vlahos and Matt Leighninger

Introduction: A Quiet Revolution in Public Meetings

Public meetings are a bedrock of local democracy, involving spaces where policy meets the people. Yet public engagement in these meetings is in crisis across the United States. Surveys show declining trust in government at the federal level. Nationwide, 85 percent of Americans say elected officials don’t care what ‘people like them’ think, and only about 25 percent feel heard by local officials. That distrust is even more acute among younger, lower-income, and BIPOC individuals, many of whom report feeling excluded from decision-making processes.

Creating civic contextual opportunities for people to feel heard is vital to today’s contested and sometimes polarized political atmosphere. This especially rings true for public meeting formats, which have been criticized for amplifying the loudest voices, sidelining historically underrepresented groups, and prioritizing performance over genuine dialogue. Traditional meeting structures, often codified in sunshine laws, guarantee transparency, not equity or impact. That said, the laws that codify public opportunities in official meetings tend to be broader than often assumed, leaving space and maneuverability for innovating meeting structure and public engagement.

For example, in Boulder, Colorado, a new experiment is unfolding. In collaboration with the National Civic League, the City of Boulder launched a bold pilot: the Community and Council Forum. This article unpacks this innovation’s design, impact, and implications, focusing on how one city is reshaping its civic infrastructure.

Context: Boulder’s Civic Ecosystem and the Problem with Public Meetings

Before the Forum, Boulder’s city council meetings looked like many across the U.S.: a standardized format with a standard public comment period during meetings when residents have two minutes to speak through a microphone to elected officials on a dais, with no guaranteed response. Despite relatively high civic interest in the community, engagement skewed toward the same familiar faces, with some meetings dominated by performative outrage. To be fair, this scenario is omnipresent. If there is any opportunity to participate in person, nearly every official public meeting in America revolves around this traditional formal comment period (varying mostly in name rather than in opportunities and content).

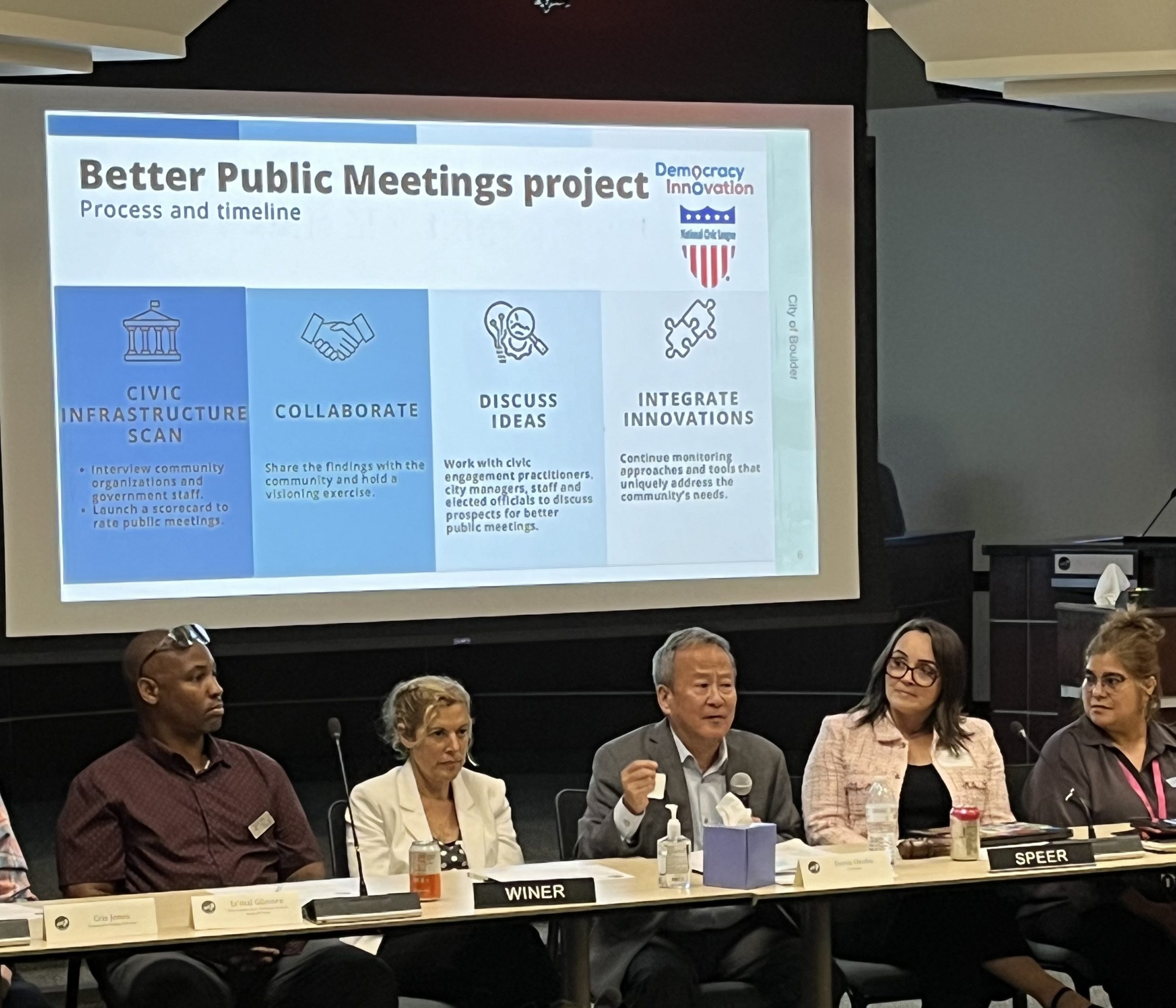

This pain point was the foundation for a project funded by the AAA-ICDR Foundation to measure and embed civility in public meeting spaces. The Center for Democracy Innovation (CDI) launched its Better Public Meetings project in 2023, with the goal of working with three pilot communities. Boulder was joined by Mesa, Arizona, and Fayetteville, North Carolina, as the three pilots.

CDI set out to collaborate with the City of Boulder’s City Council Subcommittee on Engagement and a Welcoming Council Environment and the Community Engagement department to innovate city council meetings. The process included two-pronged community-engaged research. On one hand, the research team interviewed a cross-section of local leaders. On the other hand, a scorecard was used in city council meetings for four months to get initial resident feedback on how people participate, what they like and thoughts on what to innovate. This process culminated in a civic infrastructure scan, a community forum to reflect on the recommendations, and animated resident conversations in local media. Then, one of the recommendations was implemented, namely, experimenting with a change in the format of public comments.

The scan outlines how Boulder has strong participation networks through nonprofits, advocacy groups, and neighborhood associations, as well as a highly educated population, but a weak bridge between those networks and the city’s formal policymaking spaces. The report highlighted a need for new formats that could foster civil dialogue, broaden participation, and create genuine opportunities for residents to shape decisions.

Data-Driven Insights: What the Scorecard and Interviews Revealed

Before the Forum, CDI conducted a Civic Engagement Scorecard across seven council meetings. The findings revealed that:

- 14 percent of participants were first timers

- 76 percent felt they had a chance to be heard, but 60 percent did not understand how their input influenced decisions

- Participation skewed white and older; 14 percent asked for greater demographic diversity

- Most common feedback: make meetings more interactive, accessible, and responsive

Relatedly, in-depth interviews provided additional nuance:

“There’s a difference between being heard and being listened to.”

“Public comment happens after decisions are made. It’s too late.”

This qualitative feedback underscored the emotional dimension of civic alienation. People didn’t just want to speak, they wanted acknowledgment, dialogue, and impact. They might be allowed to speak, but there’s rarely acknowledgment, clarification, or indication that their input is considered. One interviewee reflected that “the structure itself is the barrier,” emphasizing how the conventional setup, like the time-limited speaking slots, lack of back-and-forth, and absence of response, creates an atmosphere that discourages meaningful interaction. “It tells you your voice doesn’t matter.”

Others described the experience of public comment as “cathartic but not collaborative,” noting that many community members are “talking to straight faces who aren’t responsive,” particularly when public input comes “after decisions are made, it’s too late.” One participant described this dynamic as “performative inclusion,” where public comment satisfies legal requirements but offers little substance in shaping policy.

Another emphasized the psychological toll of these environments: “If you say something people don’t like, it’ll be screenshotted and posted on Twitter.” Others expressed that without transparency around decisions or who speaks to which issues, “it feels like council already knows how they’re voting.” The lack of feedback loops breeds a perception of futility, particularly among underrepresented voices who already face cultural or linguistic barriers. As one community leader put it: “There’s 108,000 people in Boulder, and there’s probably 107,000 people we never hear from.”

People of color and non-native English speakers felt especially marginalized. One Latino participant noted, “We don’t really know how to speak the language they use in meetings,” and described meetings as “intimidating and uncomfortable,” especially when condensing their concerns into two minutes at a microphone. This can be compounded by a sense of invisibility, when members of marginalized communities serve on boards or commissions, they sometimes feel tokenized.

The qualitative data revealed that public dissatisfaction isn’t just about altering procedures; people want to feel seen and respected, not simply permitted to speak. The call was to foster two-way communication early into a policy process and actively demonstrate how feedback is used. Trust in institutions grows when people understand how their voice contributes to decisions. Without that, even the most well-intentioned engagement efforts risk alienation.

Designing Deliberation: The Community and Council Forum

After various iterations and presentations before the city council, the innovation that would be implemented was reimagining the traditional study session as a space for structured dialogue. On September 26, 2024, Boulder piloted its first Community and Council Forum (the Forum), co-developed by CDI, city staff, and a city council subcommittee. Instead of a dais and time-limited comment periods, the event featured:

- Roundtable seating that dismantled physical hierarchies

- Randomly selected and demographically balanced participants (10 residents were from historically excluded communities to draw upon their lived experience, and another 10 from a general public call)

- Plenary presentations to ground discussion in shared knowledge

- Facilitated breakout groups combining officials and residents

- Post-event evaluation to capture feedback and improve design

More than a public meeting, the Forum was a democratic reframe of the study session, a type of official council meeting typically closed to public input. By design, the Forum fostered learning, listening, and co-creation. Five facilitated breakout tables, each with council members and residents, engaged in deliberation around economic vitality: what it means, what barriers exist, and what solutions are possible. A culminating plenary allowed groups to share takeaways and pose questions.

The Forum also featured an intentional participant recruitment strategy: half were invited from less often heard constituencies (e.g., youth, renters, Spanish speakers), and the other half were drawn from a public lottery. This structure reflected a core value of deliberative practice, balancing inclusiveness with representativeness. Moreover, the theme of economic vitality was topical and relevant to the community.

Community Reactions: Building Trust, Dialogue, and Mutual Respect

The Forum’s reception was overwhelmingly positive:

- Staff praised the event’s atmosphere: “People had more nuanced conversations instead of rushing 2-minute comments.”

- Council members noted: “Great dialog with people I might never have talked to.”

- Residents shared: “I met people I enjoyed learning from… it was dynamic and I felt heard.”

Post-event scorecard ratings improved across every metric: perceptions of meeting efficiency, sense of being heard, and quality of civil dialogue all rose. Even initially skeptical council members expressed support for making the format recurring.

The Forum also shifted expectations around power and process. It humanized governance by removing the dais, inviting dialogue, and embedding deliberation within the legislative rhythm. Participants who were skeptical at first expressed surprise and gratitude for being part of something meaningful. The Forum’s proof-of-concept success was grounded in its design to create procedural equity and relational trust. This mirrors Jonathan Collins’s 2021 findings that more participatory and deliberative meetings increase trust in local government and willingness to attend future meetings, particularly among marginalized communities.

From One Pilot to Civic Infrastructure: Opportunities and Next Steps

The Forum feeds into a larger civic strategy. In fact, the city has implemented a community assembly on their Comprehensive Plan. The city is exploring ways to expand deliberative opportunities within formal governance. These efforts contrast with older paradigms of public engagement that prioritize transparency (e.g., sunshine laws) but rarely include public deliberation and decision-making or early-stage participation. Sunshine laws might ensure openness but do little to improve engagement quality. Boulder’s pilot, by contrast, inserts structured dialogue and learning directly into the legislative process, shifting from reactive to proactive public engagement.

Feedback from the Forum helped shape Boulder’s Economic Vitality Strategic Plan. The plan now includes expanded support for BIPOC and micro-businesses, participatory budgeting models, flexible zoning, adaptive reuse incentives, and an “Affordable Commercial Space” initiative. Informed by the Community and Council Forum, the plan now includes:

- Equity and Inclusion: Community members, including BIPOC entrepreneurs, home-based business owners, and nonprofit leaders, emphasized the need to reduce systemic barriers. In response, the plan expands technical assistance, develops microloan programs, and broadens outreach and contracting opportunities to historically excluded businesses.

- Economic Vibrancy: Participants challenged the notion that vibrancy means growth alone. Instead, they called for preserving Boulder’s distinct identity while fostering innovation. The plan includes stronger city coordination that is less reliant on intermediaries like chambers, and proposes streamlined navigation tools, business education supports, and targeted outreach to underserved sectors.

- Commercial Vacancy and Zoning Reform: Concerns over increasing downtown vacancies and rigid land-use policies led to new strategies that promote adaptive reuse, flexible zoning for emerging business types, and incentives for filling empty storefronts.

- Affordability for People and Businesses: Echoing concerns about cost-of-living and commercial displacement, the plan promotes affordability by supporting employee ownership transitions, piloting the Affordable Commercial Space initiative, and offering tools to help small businesses reduce operational expenses.

- Sustainability and Resilience: Reflecting a call to align economic goals with climate action, the plan embeds sustainability through support for green business practices, disaster preparedness resources, and incentives for resilient economic infrastructure.

- Transparency and Participation: Many residents expressed a desire to better understand how public dollars are spent and to shape future investments. In response, the city is piloting participatory budgeting elements, improving communication around funding, and embedding feedback loops through mechanisms like the Civic Engagement Scorecard.

These changes demonstrate how structured dialogue can yield tangible policy shifts, advancing transparency, trust, and impact. With continued support from city staff and council, the Economic Vitality Strategic Plan signals Boulder’s commitment to making economic development more responsive to voices in the community.

Lessons and Implications: Redesigning Democratic Institutions from Within

Boulder’s Forum demonstrates that democratic innovation is possible within government. Unlike citizen assemblies or external mini-publics, this was a formal council meeting, subject to public records laws, televised, and part of the legislative calendar.

Key takeaways include:

- Design matters: Space, structure, and facilitation influence who speaks, who listens, and what is possible

- Trust is built through interaction, not just transparency

- Inclusion must be intentional, from participant selection to language access

- Institutional buy-in is essential: support from council and staff allowed the pilot to be resourced and taken seriously

- One event is not enough: continuity and feedback loops are crucial to legitimacy

- Expand engagement channels: Initiatives like Boulder’s Community Connectors program, where residents serve as liaisons to specific neighborhoods or communities, show promise in reaching underserved populations. When paired with tools such as Lakewood Speaks (Colorado), which allow asynchronous input, cities can design ecosystems that support layered participation.

This experiment supports other research that suggests meeting structure influences civic trust and participation. Passive attendance at deliberative meetings can build confidence in local democracy, especially among underrepresented communities.

Other opportunities to further iterate on public meetings include:

- Rotating forums across neighborhoods to reduce geographic and logistical barriers.

- Embedding deliberation in council retreats. The forum’s success opens the door to broader institutional redesigns. One promising idea is democratizing the city council retreat. These behind-the-scenes strategy sessions shape policy priorities but typically exclude public input. Integrating pre-retreat public engagement, joint learning sessions during retreats, and post-retreat evaluations would help ensure community priorities are baked into the city’s agenda.

- Leveraging asynchronous participation. Time remains a key barrier to equitable engagement. Many residents can’t attend in-person evening meetings. Platforms, like People Speak, offer asynchronous input methods that allow comments to be submitted before meetings during non-traditional hours. Interestingly, the highest volume of participation often occurs midday, not during the live hearing itself. The implication? Deliberation must not be confined to a single room or time slot. Well-designed asynchronous tools can democratize participation even further.

- Using the Civic Scorecard as a feedback loop. Boulder’s Civic Engagement Scorecard served not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a feedback mechanism. It captured shifts in sentiment before and after the pilot, offering a way to track progress over time. Expanding this tool, or embedding it in other engagement initiatives, can help ensure iterative learning across departments and projects.

Conclusion

Public meetings can either alienate or empower people. Boulder offers an example of the latter, which is possible by redesigning existing institutional processes to gather feedback from the community earlier in the policy-making process and creating feedback loops for the public to reflect on how their input is being utilized. Public meetings matter most when they are responsive, trusted and inclusive of community voices. The community and council forum format offers an opportunity to learn from and iterate on new experiences with official public meetings. It is important to note that for a first attempt at such a process, it was a positive and successful experience. However, there is still more work to fine-tune the process to be more inclusive, accountable, transparent, and accessible. Boulder will continue to hone its approach; meanwhile, the next cohort of communities undertaking Democracy Innovations for Better Public Meetings will strive to integrate innovations and outreach strategies to diverse audiences unique to their contexts.

Nick Vlahos is Deputy Director of the Center for Democracy Innovation at the National Civic League.

Matt Leighninger is Director of the Center for Democracy Innovation at the National Civic League.