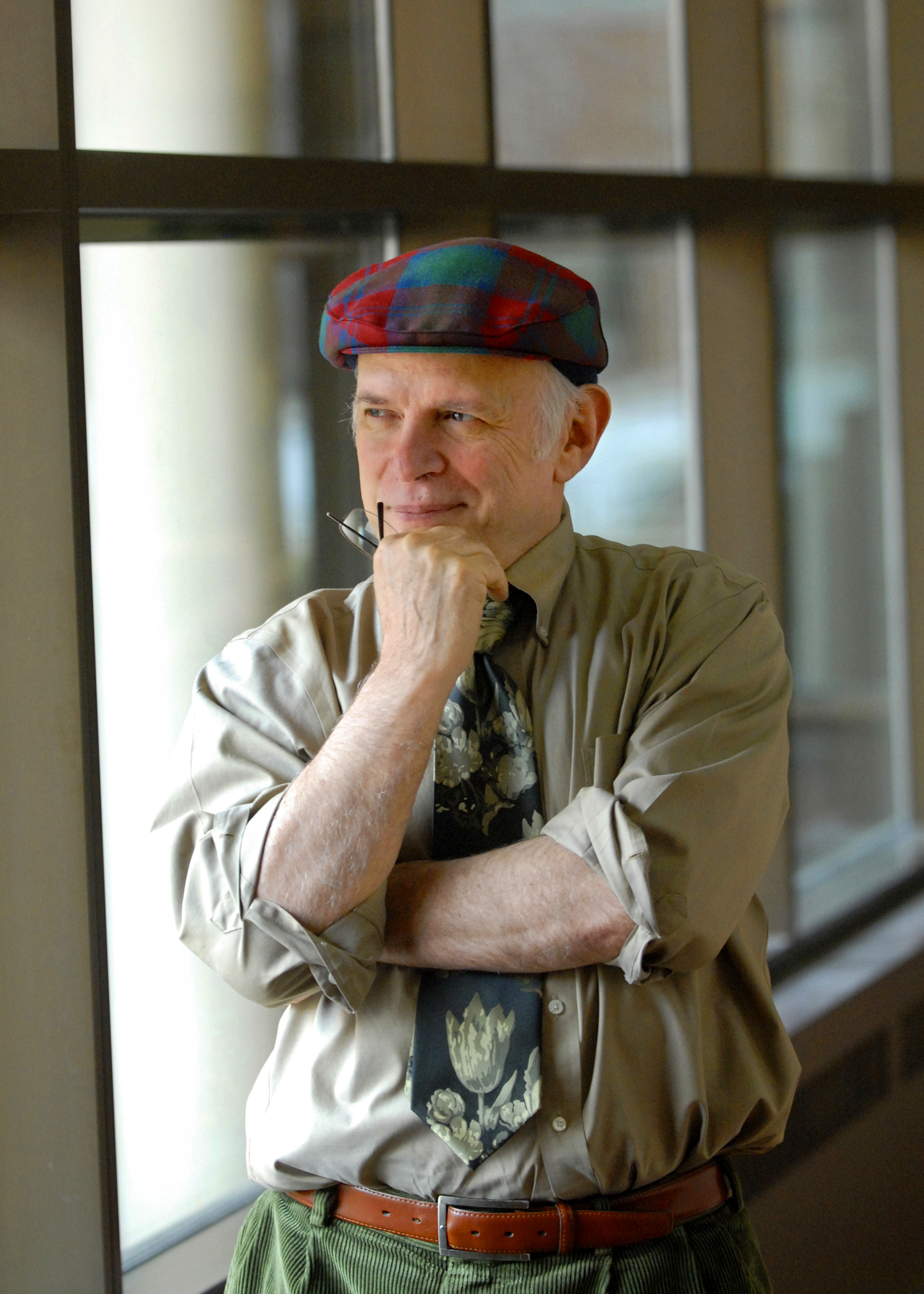

Editor’s Note: Harry C. Boyte is Senior Scholar in Public Work Philosophy at Augsburg University and founder of Public Achiement, a youth civic engagement program. As a young man, he worked as a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Martin Luther King’s organization, in the civil rights movement. Boyte’s public work approach to civic engagement and democracy has gained world-wide recognition for its theoretical innovation and its practical effectiveness in translating lessons from community organizing into institutional and professional change. Boyte’s most recent book, Awakening Democracy through Public Work: Pedagogies of Empowerment, is an introduction to his thinking on citizen action, social change, and civic education.

Albert Dzur is a Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Philosophy at Bowling Green State University and a National Civic Review contributing editor. His most recent book is Democracy Inside: Participatory Innovation in Unlikely Places. He began his conversation with Harry Boyte with a question about Mike Huggins, a former city manager in Wisconsin, who worked with county officials to launch the Clear Vision Eau Claire, a communitywide public engagement initiative. After retiring, Huggins continued to work with the nonprofit organization that emerged from the initiative. Huggins wrote about the evolution of Clear Vision Eau Claire in the summer 2018 issue of the Review. Read Dzur’s review of Awakening Democracy through Public Work.

By Albert Dzur

Beyond Technique: Towards a More Democratic Form of Professionalism in Public Administration

Albert Dzur: You end your new book, Awakening Democracy, by talking about city government in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. What can city managers and public administrators learn from this story?

Harry Boyte: People can take a number of things from Mike Huggins’ experience in Eau Claire, from the quotidian to the larger scale. It is obviously a very powerful story of a city manager who became a citizen professional, or democratic professional, and that meant a different identity and a different set of practices. And also, a different sense of possibility. I don’t think, actually, that this can be underestimated. In any constrained, rationalized, instrumental environment these days, just breaking this sense of fatalism is foundational.

Harry Boyte: People can take a number of things from Mike Huggins’ experience in Eau Claire, from the quotidian to the larger scale. It is obviously a very powerful story of a city manager who became a citizen professional, or democratic professional, and that meant a different identity and a different set of practices. And also, a different sense of possibility. I don’t think, actually, that this can be underestimated. In any constrained, rationalized, instrumental environment these days, just breaking this sense of fatalism is foundational.

Mike Huggins is a good example of a citizen professional. I was trying to distill out from the stories in the book a simple definition of citizen professional that could resonate easily. A citizen professional is someone who learns to work in a collaborative way to turn whatever setting they have authority over, or around–it could be a school or a library, it could be a beauty parlor–into a more purposeful, humane, democratic, empowering, and community-connected site or environment.

All the powerful stories in the book are about that kind of transformation. But Mike’s is a community-wide story, which actually shows the tremendous potential of city managers if they learned to develop a different understanding of themselves and their work, to develop the skills and the confidence to do it, to build the support networks, and to take advantage of the political openings. Mike’s story has all those features.

It is also an important story for our time. Across the board from liberal to conservative, to political theorists to journalists, what could be called the democracy imaginary has radically shrunk. A lot of things feed that, and theory is not an insubstantial factor. It’s amazing to see the shrinking of definitions of democracy in the work of someone like Robert Putman, whose first book, Making Democracy Work, was on the interaction between regional governments and the civic culture. And in his last book he goes straight to Robert Dahl and says democracy is what happens in government. Wow!

The Eau Claire experience counters such shrinking of the democratic imagination with a story of re-growing a broad, inspiring, energizing understanding of democracy and then nourishing that with sustained practices and intense civic education. It’s still a work in progress, of course, but democracy has come to life in Eau Claire.

Dzur: I want to pick up on a word you just mentioned: “identity.” A change in identity led to innovative practices, led to a bigger sense of possibility. I’m wondering what catalyzed this shift in identity?

Boyte: There are several things in Mike’s case. One is that Mike loved Eau Claire. He decided not to go on the typical track of an ambitious city manager and on the look for bigger and more prestigious jobs. He and his family loved the place. They thought there was something special about it. They appreciated the rich civic history there. And they created a lot of relationships there. The importance of that can’t be underestimated.

Then on top of that are some key factors he identifies in his own experiences in Eau Claire. One is the underage drinking project with eight communities that our Center for Democracy and Citizenship worked with in the 1990s, along with the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Minnesota. The department took a traditional medical expert-knows-best “fix-it” approach, which they called community organizing. So, we had this lively debate with them for three years. I argued that what they were talking about wasn’t organizing. They knew exactly what they wanted the communities to do. They had a predetermined outcome, and they wanted us to get them to do it. We said, “Well, you can find someone to do that, but that’s not what we do.”

Dzur: What we see all around us, though, are community engagement efforts facilitated by professionals that are more managerial than democratic. They’re intended to justify or legitimate whatever it is that the city wanted to do to begin with. I’m struck, when I talk with city managers who are otherwise amenable to the idea of community engagement, by how unsettled many are by the thought of real power-sharing and public engagement. I wonder if their concern about instability is an obstacle to becoming more of a democratic city manager. How do you overcome that fear of the unstable or chaotic public?

Boyte: That’s a great question. On one level, it’s a matter of people with positional power who are worried about what could happen if they weren’t in control. This is a very old dynamic. When Sara Evans and I were doing the Free Spaces book, we found this quote from a minister who in 1859 refused women the right to have a prayer meeting in his congregation saying, “Who knows what they would pray for if they did it by themselves.”

During the period when we were working with the Clinton Domestic Policy Council, I remember our first meeting in the Roosevelt Room with a number of agency leaders and undersecretaries, convened by William (Bill) Galston of the Domestic Policy Council. We brought in David Brown, who had worked with questions of professional practice for many years and was a keen observer of the challenges. David said to the whole group,

“Now look, we can talk about civic engagement ‘til the cows come in, but the fact is almost all of your agencies and managers are scared to death about what would happen if they don’t know the outcomes in advance.”

-David Brown

Dzur: That seems exactly right.

Boyte: And so, there’s need for trust in people’s capacities and intelligence and talent and also in the process, that people are going to be creative if they are self-directed. This is something we have also found, of course, in a different way, with our Public Achievement civic education and empowerment initiative, in the case of teachers. Creating a free space where kids are actually taking the lead in their own projects and making the rules is very threatening. It’s also threatening for city managers.

I think there are things that help to assuage the fear. One is seeing things and telling stories and talking to people. Peer relationships and hearing from other city managers who have had success makes a difference. One cannot underestimate the simple fear and anxieties involved.

Dzur: Among city managers who are interested in a more democratic form of professional identity, they recognize that they’re working in a dysfunctional political environment, but many are still looking for a technique. They’re looking for a gold standard way of engaging the public, an established protocol, a best practice. But that’s not how it works, is it? It’s not a technique.

Boyte: No, it’s why the jazz metaphor is useful, I think, whether in Public Achievement or more broadly in co-creative, public work politics. It’s an iterative, open process. There are skills, capacities, talents. There’s a craft and art to it. But it’s an open process and you can’t predict that outcome. You can affiliate such co-creative politics with complexity science and so forth, and the concept of emergence is pretty useful, but on the ground, it’s simply a different kind of politics that has to be learned.

Broadening and Deepening Civic Education: An Action-Oriented Philosophy

Dzur: I was struck by some of the stories in your book of schools where Public Achievement had been thriving, but then faltered because of a change in school administration. That’s not an uncommon thing to happen with democratic innovation. What are your thoughts on how to overcome these difficulties in order to sustain democratic practices?

Boyte: One can’t minimize the difficulties. The challenge is that in rationalized, efficiency-minded education these days, it’s really counter-cultural to sustain something different and democratic.

Dzur: Right.

Boyte: It takes a bold leader who not only has a vision, but also the skills to work with people differently and to inspire. The dynamic is clear in many democratic experiments. One of my mentors is Deborah Meier, whose Central Park East schools in Harlem became national models. Some of the principals who succeeded her over the years were on the same wavelength. And Mission Hill in Boston has pretty much continued. But Central Park East’s democratic spirit has faded, in her view.

In tight, constricted, rationalized educational cultures teachers feel cowed, under the gun, judged, and insecure, so they don’t want take much risk. And principals don’t usually know how to help. So, in the main, sustaining democratic cultures is difficult. But then there are also contrasts, as you can see in the book. As difficult as the challenges are in American schools, Eastern Europe is a lot more difficult.

Dzur: That reminds me of a Midwestern saying, when you ask someone how they’re doing: “It could be worse.”

Boyte: On the other hand, I don’t think we’ve seen anywhere in America where there was the kind of natural resonance of African communities in which Marie Ström has worked. In places like Burundi, where she worked with a network of adult educators to ground and root public work concepts in the local culture through storytelling and other means, public work politics has had tremendous resonance and impact.

Professional Education and the Role of Universities in Democratic Renewal

Dzur: This raises the question of the role of higher education. One thing that struck me when researching democratic schools like those Deborah Meier is devoted to is just how absent professional education is in this. In fact, people who become democratic teachers or democratic principals have to go against their training!

Boyte: Deborah Meier said the first thing that happened in Central Park East when they were getting going was they had to unlearn what they had learned in teacher colleges. They’d learned to think that education was about imparting knowledge through various kinds of instructional pedagogies rather than building relationships with kids or parents. That was completely outside of the teacher education.

Dzur: What has always impressed me about your work is that you’ve never pushed an anti-professionalism line of argument. You’ve always felt that you can do professionalism differently. To be more democratic does not mean becoming a less professional teacher or public administrator.

Boyte: Right.

Dzur: It’s about becoming a professional teacher or public administrator in a different way.

Boyte: I would say that is really key. I’ll give a genealogy of public work here. We started in 1987, when the first theoretical statement was the CommonWealth book, looking in more depth at the Industrial Areas Foundation network. I was impressed by their leadership development, and also in the transformative change in some of the professionals I’ve talked to. But they never found a way to name that. In fact, I had a debate with Ed Chambers, director of IAF, in 2004 at Duke. I said, “You know, you’re missing out on democratic professionals.” He said “Bullshit.” He could be an irascible guy. “That’s just a bunch of crap! The only professional who is any good is an organizer. Every other one is an enemy.”

Dzur: That’s not an uncommon argument, and it is a really strong element in some otherwise very useful theories of organizing.

Boyte: My animus in the beginning of our work through the Humphrey Institute (now school) was to recognize that the rich civic learning cultures in groups like the Industrial Areas Foundation were also imprisoned by their organizational form. Their democratic dynamic doesn’t break out into the main life of the society. They are oases of democratic life in a desert of technocratic and market practices, so they don’t have a large cultural impact.

Our original mission was to name the democratic practices of the freedom movement and IAF as a politics, called citizen politics, that could be taken elsewhere. I didn’t explicitly name it as a non-violent politics, although that’s what it was. I brought Dorothy Cotton in all the time to talk about the movement. Our question was, “What happens when you take nonviolent citizen politics into institutions?” We had a cohort of institutions in what was called Project Public Life including Minnesota extension, the College of St. Catherine, schools like St. Bernard’s, the Metropolitan Regional Council and Augustana Nursing Home. E.J. Dionne had given me good counsel, saying, “You should find a group of institutions close to home, in Minnesota, that you can work with over time and see what happens.” And that was wise. It allowed a lot of cross-institutional fertilization.

As soon as we began bringing citizen politics and civic organizing practices into institutions, the constraints and the narrowness and the bubble cultures and the sub-disciplinary specialties of work rose straight up to the top.

We were fighting cultures where critical care nurses in the nursing home didn’t know how to talk to the occupational therapists, much less the residents. That was when we started talking about the public qualities of work, and the purposes and the practices undergirding all that.

Dzur: It’s not an easy program to articulate because professional training and professions themselves have promised so much. Police promise security. Prosecutors and defense attorneys and judges promise justice. Teachers promise education.

Boyte: And doctors promise health.

Dzur: Exactly. Health and well-being. So, this alternative approach has to cut down on those promises. But that’s a very seductive discourse, to say, “We deliver the goods.” And the critical discourse has to say, “No you don’t deliver the goods, but here’s what else you could do.”

Boyte: Absolutely. And say, also, “You can be a catalyst. You can have tremendous and greater power, but a very different kind of power.” I think that the power thing is really important.

Dzur: Right.

Boyte: Young people really respond to the idea of citizen professional. We see this all the time in the undergraduate class of Dennis Donovan, at the University of Minnesota. It’s a most remarkable class with every political ideology, football players, women’s basketball players, business students, always racially diverse. They love the diversity and the fact that they mix it up. In their papers, many get most excited about the idea of the becoming a different kind of professional, and all of the associated terms and phrases like “on tap, not on top,” “working collaboratively,” and the biblical example of Nehemiah. It opens up a way to imagine making a difference in the world through one’s work. And even in the richest civic engagement experiences in colleges, these ideas are not much discussed.

I actually think that is the new frontier and we just have to figure out how to make it happen, because the civic movement in higher education doesn’t do this.

Dzur: That indicates that mainstream technocratic or managerial professionalism may be losing some attraction.

Boyte: There’s no doubt with young people today. Students want something else.

Dzur: They don’t really believe in the hollow promises of mainstream professionalism.

Boyte: They don’t. And they’ve never even had a way to name an alternative. And they’ve never had examples.

Dzur: Maybe this is an iterative process: as different kinds of courses are offered and different ways of looking at professions become more common, students will demand more.

Boyte: I think it is an iterative process. Students will demand something different if they know it’s possible. Rick Battistoni and Tania Mitchell published a longitudinal study, in Diversity in Democracy last June, a study of alumni from three different institutions over about ten years. These were Providence, U-Mass Amherst, and Stanford, all of which have pretty robust civic engagement cultures. And the thing that overwhelmingly comes out in this research is that students don’t want to stop having a public life when they get out. They don’t want to be off-hours volunteers; they want to figure out how to bring these things into their work, and they don’t know how to do it.