By Michael Abels

Local governments are facing levels of political negativity and ideological polarization not foreseen by past scholars or adequately described in the public administration curricula taught at colleges and universities. The fundamental political schism that is dividing American society and our political system is placing appointed managers into unsustainable positions, so they must rethink how they identify issues and recommend policy solutions to elected bodies who are deeply divided into opposing ideological camps.

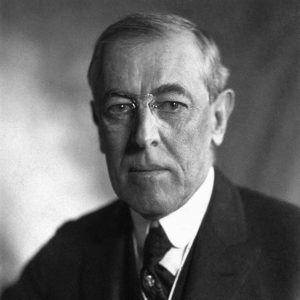

In addressing this new era of mistrust and polarization, it would be useful to look at our history and how public administration and city/county management have evolved. An excellent historical place to initiate our discussion is with Woodrow Wilson, a prominent leader in promoting the council-manager form of government and an influential scholar who some consider to be a founder of public administration in the United States.

Wilson’s foundational reputation derives in part from his 1887 article, the Study of Administration, in which he argued that government was becoming so complex that effectively managing public programs required administrative and organizational skills separate from the political skills necessary for legislatively enacting programs. Wilson’s career as a professor of political science, President of Princeton University, Governor of New Jersey, and lastly as President of the United States may provide valuable lessons for local managers and political leaders as they address today’s policy issues. But at the outset it must be acknowledged that several of the policy applications followed by Wilson provide lessons because they are the antithesis of effective leadership practices.

Woodrow Wilson Lessons for 21st Century City Management & Public Administration

To begin, the politics-administrative dichotomy that Wilson framed in the 19th century has been fundamentally transformed. Today’s operative model does not strictly separate administration from the political; instead, politics, policy, and administration are mixed into an amorphous blend that is largely shaped by the political and cultural realities of individual political jurisdictions where it is applied. Probably the foremost area of tension in the field of city management and public administration is the debate about the proper structure of organizations and the optimum form of service delivery. This tension is reflected in the dichotomy between managing hierarchical, unitary, centralized organizations versus decentralized, matrix, networked-collaborative organizations.

To begin, the politics-administrative dichotomy that Wilson framed in the 19th century has been fundamentally transformed. Today’s operative model does not strictly separate administration from the political; instead, politics, policy, and administration are mixed into an amorphous blend that is largely shaped by the political and cultural realities of individual political jurisdictions where it is applied. Probably the foremost area of tension in the field of city management and public administration is the debate about the proper structure of organizations and the optimum form of service delivery. This tension is reflected in the dichotomy between managing hierarchical, unitary, centralized organizations versus decentralized, matrix, networked-collaborative organizations.

A second increasingly fraught subject among local government managers is identifying the new role for appointed managers in recommending policy alternatives to their elected officials, who as previously mentioned, are increasingly divided into ideological camps. Assisting managers in answering this issue may become an important new mission for professional organizations who focus on public service.

As Wilson perceived in the 19th century, issues confronted by 21st century managers are very complex. This complexity is coupled with political ideological rigidity that sees political leaders interpreting the same set of facts through totally different lenses. Successful administration requires that managers search for integrative solutions, develop coalitions and networks of mutual responsibility, and delegate power to solve problems that transcend organizational boundaries. In his 1908 book, Constitutional Government in the United States, he wrote that “synthesis is the whole art of government.” Wilson displayed an excellent example of managerial synthesis with the skills he used to organize his war cabinet as well as the delegation of responsibility and authority he gave to his cabinet officers.

At the same time, using networked management to attain synthesis lacked theoretical foundation in the early 20th century. Following the central administrative philosophy of his time Wilson believed in hierarchical authority with clear lines of centralized accountability. Networked systems, which are essential in the 21st century, were not common in Wilson’s time.

In 2023, while serving as the interim city manager for Flagler Beach, Florida I witnessed two excellent examples of effective networked, collaborative management. First, the Flagler Beach City Commission persuaded Flagler County and all cities in Flagler County to jointly participate in quarterly meetings where policy-service problems were recognized, and joint solutions could be identified. Designing collaborative solutions that linked multiple governments served as a force multiplier. Through joint action each government could successfully address problems that individually they did not have the resources or authority to overcome.

Secondly, in 2022 a series of storms devastated the coastal beach and city fishing pier. The federal Corps of Engineers, the state Department of Transportation, Flagler County, and the city all had discreet areas of responsibility but could not solve their issues unilaterally. Therefore, all four jurisdictions formed a collaborative team in which “all were in charge-all were accountable,” and collaborative approaches to repairing the comprehensive damage to the coastal areas were designed. Fulfilling my interim position, I concluded that the integrative solutions designed by this collaborative team represented the optimum solution for effectively addressing cross jurisdictional problems. Following the traditional single jurisdictional command and control model will fail when an issue transcends the jurisdiction of one government entity. Today, most significant issues affect multiple governmental bodies.

Observing this excellent example of collaboration, an additional conclusion was reached. Forming networks and facilitating collaborative partnerships is much more difficult to establish at the higher levels of political-organizational command because there, political influences become dominant in shaping decision making. Because of this reality, networked collaborative systems are best designed and implemented by managers at the operational field level.

What additional Wilsonian lessons can serve as a guide for managers in our era of multi-jurisdictional problems?

Brian Cook, in his book analyzing Wilson and public management, states that Wilson saw leadership anchored on emotions and believed that leaders must first appeal to the public’s emotions before they considered rational solutions. Ideas advanced by leaders must be simple and easily understood. Cook’s analysis is supported by an 1890 commencement address made by Wilson titled “Leaders of Men.” Wilson said that men could not lead without “insight into the heart rather than the intellect” of those they lead. Wilson saw emotional empathy as a critical skill necessary for leaders to gain the confidence of those they lead. Wilson enhanced this point by saying logic should not necessarily be a strict value for public leaders.

He also said that public leaders are trained to assume that one plus one equals two and that the public understands this reality. He refuted this line of reasoning by saying that if the people believe that one and one equals something other than two, political leaders will have to legislate based on that reality. However, political leaders following Wilson’s reasoning and legislating on false beliefs are contributors, if not the cause of today’s political and societal dysfunction. Contrary to Wilson’s conclusion, political leaders must first be truthful educators of the public with the courage to remain steadfast in their role as truth tellers even when doing so confronts them with personal political peril.

In the speech Wilson also called for leaders to set policy through a focus on the short-term (and not for a future) that people were not currently experiencing. He said leaders “must lead your own generation, not the next.” This idea could explain why environmentalists find it difficult to rally the public around solutions that have immediate costs but whose benefits are designed to address long-term damages caused by climate change.

People are reluctant to incur immediate costs for problems they cannot readily identify in the present. Countering this reality and rejecting Wilson’s conclusion about the telling of truth are especially pertinent in our era of ideological division. In their leadership role public administrators, elected and appointed, must be educators as well as positive visionaries, helping the public understand the truth of our current reality and how policy must be designed to ensure a prosperous future for the generations to come.

Leadership anchored by emotional influence, confined by a short-term horizon runs counter to the rational analysis, optimum solution model taught as a management practice in public administration. In our time of extreme political division with public fear generated by conditions spawning uncontrollable life events e.g. climate change, the administrative and political understanding of the public’s emotional fears is a critical skill. In Flagler Beach I saw the necessity to plan public initiatives by first responding to the emotions of affected citizens. To address climate-generated flooding issues that threatened people’s homes, we first had to ensure citizens believed staff understood their urgency and that cost would not be the determining factor in deciding the solution to implement.

In his writings, public administration luminary Marshall Dimock wrote that Wilson recognized government must look outward and be responsive to divergent public interests. Dimock concluded that while Wilson advocated hierarchical chain of command systems, he also believed that government could not be solely driven by efficiency. Cook agreed with Dimock when he referred to Wilson’s writing in Congressional Government, which suggested that administration must be somewhat inefficient as it responds to conflicting public needs.

Important Lessons Wilson Provides to 21st Century Leaders

In the era he identified with complex change, Wilson failed as a collaborative leader. From proposing dramatic academic changes at Princeton University to successfully implementing vital domestic programs as president, Wilson perceived how the demands of the future necessitated fundamental policy change in academic and national domestic policy. The League of Nations was a visionary concept Wilson endorsed to ensure world peace. Like his major reforms at Princeton University, this initiative failed because of his ultimate weakness as a collaborator. However, the wisdom of Wilson’s vision was demonstrated years later through the collaborative formation of the United Nations and other internationalist organizations.

For today’s leader Wilson’s history yields two additional lessons. First, leaders must be oriented to the future by identifying that future through collaborative strategic planning. Secondly, leaders must not have preconceived ideas of how the future will develop or what initiatives must be implemented to shape the forecasted future. Organizational stakeholders must collaboratively concur with the planning process outcomes as well as the implementation strategy designed to attain that future.

As this article describes, there was a dichotomous, ineffective side to Wilson. Without question, Wilson was an idealist who strove to accomplish visionary change. Arthur Link described Wilson’s self-perceived mission as one of believing he was serving all of mankind. Because of his conviction about the self-righteousness of his mission, coupled with his belief in a strong executive working through unified party government, Wilson excluded influential Republicans such as William Howard Taft from serving on the team he took to Paris for negotiating the Treaty to end WWI. Upon returning from Paris, he hosted a luncheon with the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee. His foremost Republican adversary, Henry Cabot Lodge, and other influential Republicans attended this luncheon. For three hours Senators rationally questioned aspects of the treaty, especially the League of Nations.

While providing answers to those questions Wilson never explored with those Senators acceptable reservations that could be incorporated as part of the legislation but would not require amending the treaty. Wilson’s advisors pleaded with him to accept some reservations to the treaty because their support would be needed to win approval in the Senate. Wilsons failure to follow this advice was especially egregious, since in 1918 both houses of Congress were controlled by the Republican Party and the need for Republican support to attain two-thirds approval of the Senate was self-evident.

While in Wilson’s writing and executive actions, he referred positively to synthesis and negotiated solutions, historians view his leadership style in terms of viewing policy through a moral, righteous lens. He believed compromise was equivalent to a loss of integrity. In “Leaders of Men” Wilson stated that leaders are “champions of moral principle” and “do not always wear the harness of compromise.” Wilson’s unyielding philosophy led the Senate and thus the United States to ultimately reject the League of Nations. As Wilson had forecast, by rejecting the League of Nations the United States “broke the heart of the world.” As he and others feared that rejection was a significant factor that would lead to a second world war.

Lessons Managers & Elected Officials Can Use Today

The management-leadership principles developed and practiced by Woodrow Wilson provide wisdom, fundamental contradictions, and in some cases antithetical leadership guidance to today’s public managers and elected officials. Wilson’s speeches offer positive insight to the 21st century public leader when he identifies that public leaders must appeal to the emotions of citizens as a foundation for solutions to public problems, and, that leaders must understand that the public is short-term oriented. However, Wilson wrongly concluded that, as the foundation of policy, leaders should accept the public’s incorrect conclusions about facts. Instead, effective leaders must unwaveringly educate the public about the facts surrounding societal issues and the policies being considered to address them.

The wisdom of visionary leadership Wilson expressed in his writings, speeches and his presidential policies formed the basis of the progressive programs known as New Freedom. Many programs in New Freedom, for example, the Federal Reserve Act, approval of an income tax, continue to serve as a foundation for 21st century national policy. However, Wilson’s moralistic decision to not compromise on the League of Nations represents the antithesis of effective leadership and is refuted by the effective collaboration described in this article, where governments unified to address multijurisdictional problems and four levels of government jointly designed solutions to beach destruction caused by storm events generated from climate change.

Woodrow Wilson’s history provides us with three important guideposts. Foremost, leaders in the 21st century must be collaborators, mobilizing all who are impacted by current issues. Secondly, leaders must address issues considering the emotional needs of their affected citizens. Emotional reality must be a priority component of rational analysis. Efficiency of the solution will be a lower priority than addressing emotional fears and needs of citizens. Lastly, effective leaders will be educators of current and historical truth and guide their communities in identifying a common vision that will benefit future generations.

Michael Abels is a retired lecturer and a former city manager.