By Albert Dzur

From Wicked Problems to Collaboration

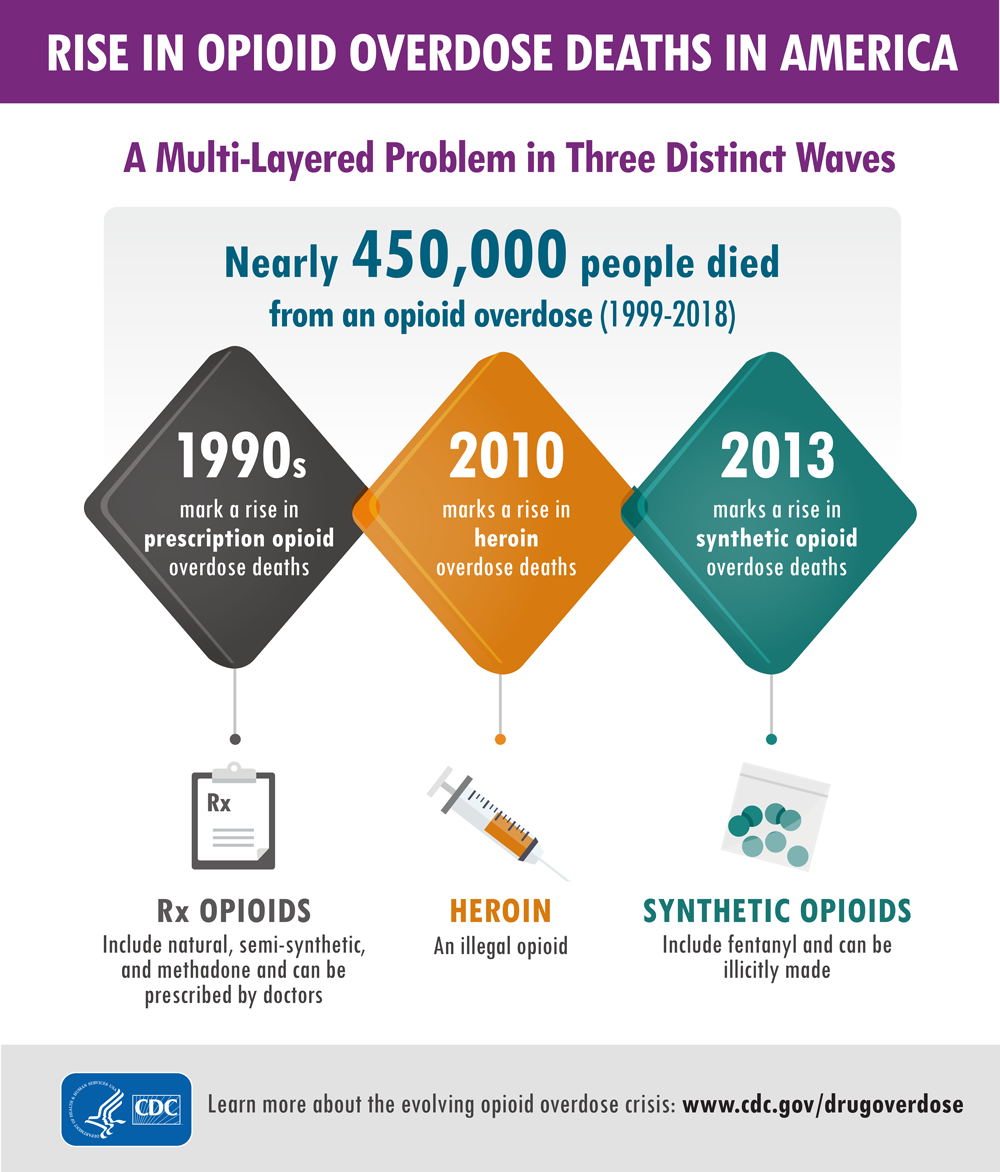

The concept of “wicked problems,” first developed by planning theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in the early 1970s, perfectly captures what some observers have called America’s “other epidemic.”1 The opioid addiction crisis is a multi-faceted social problem that is difficult to define, where possible policy solutions have unpredictable and potentially negative repercussions, about which there are a range of normative perspectives and conflicting values. A commonsense approach is to suggest a nesting of collaborative professionals in health care, law enforcement, and government working together with highly engaged and alert citizens.

The concept of “wicked problems,” first developed by planning theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in the early 1970s, perfectly captures what some observers have called America’s “other epidemic.”1 The opioid addiction crisis is a multi-faceted social problem that is difficult to define, where possible policy solutions have unpredictable and potentially negative repercussions, about which there are a range of normative perspectives and conflicting values. A commonsense approach is to suggest a nesting of collaborative professionals in health care, law enforcement, and government working together with highly engaged and alert citizens.

There is an important distinction to be marked, however, between collaboration with fellow professionals and collaboration with citizens, a process I will call “coproduction” or “doing with” in this article. The former may be much easier to accomplish than the latter. Looming large in the background for Rittel and Webber was public distrust of professionals. Despite modern advances in public health, education, transportation, and infrastructure, chronic problems drove skepticism about professional expertise and ability.

In Rittel and Webber’s era, public distrust was fostered by a growing sense that professionals’ problem-solving capacity was more limited than the professionals themselves believed. The capacity of professionals to adequately define problems and design clear solutions that would best serve public good seemed limited across all major policy fields—from crime control and school curricula to tax rates. Today too, those coping with addiction or working on the opioid epidemic in counseling, policing, medicine, and government often speak of shattered trust in professionals, lost faith in community organizations, and wavering belief in social norms.2

Rittel and Webber never developed a constructive model of professionalism that could rebuild trust in the face of wicked problems. Later scholars, drawing on their argument, advocated a professional humility and increased openness to ground-level learning.3 Wicked problems like the opioid epidemic create pressures, motivations, incentives, and opportunities for health care providers, criminal justice professionals, and government officials to listen, learn, and work with lay citizens.

Horizontal collaboration, while more inefficient and time-consuming for handling routine tasks would become the default mode of professionalism for actors and organizations facing wicked problems. As former Hamilton County city manager Christian Sigman has recently written in these pages, the opioid epidemic demands “an innovative and structured approach to making collaboration work across government, business, philanthropy, non-profit organizations and citizens to achieve significant and lasting social change.”

Tensions and Limits of Collaboration: Public Challenges

Professional collaboration with communities on a wicked problem like the opioid epidemic is sensible, but it contains three buried assumptions: the wicked problem exists “out there” in the world, detached from the ways that professionals conceptualize and act on it; institutional flexibility, professional teamwork, and innovation can solve the problems without major institutional changes; and professionals lead the way, with citizens invited in as needed as helpers.

These assumptions can frustrate citizens who feel side-lined, as evidenced in a number of public forums held in Ohio in the past two years. Collaboration among professionals may not involve transformation of any given agency’s or organization’s mindset—one may still revolve around penalty, another around treatment, even if they are working together—nor may it involve much listening to citizens. Combining different narratives central to different professions may still be stigmatizing to their loved ones, as when “mental illness” is fused to “illegal drug use.”

Public Forums in Buford Mills

With a mixture of agriculture and light manufacturing as its economic base, and a population of 20,000 situated within 50 miles of one of the state’s biggest cities, Buford Mills looks like any one of a hundred Ohio towns. (All the names in the Buford Mills case, including the name of the town, have been changed to preserve anonymity.) Though residents view it as a safe community and one with little violent crime, “Drugs are a MAJOR problem,” according to Buford Mills’ city manager. “Drugs are on everyone’s mind.” She reports that during a recent trip to a café, the owner said, “I can’t find anyone to work for me. Everyone’s on drugs. Nobody wants to work.” A county agency providing treatment for alcohol and substance use handled over 500 cases in the year prior to the public forums, the majority of which were opioid related.

In late winter and early spring 2018, an academic center, working closely with Buford Mills’ city manager and professionals from the town’s public health department, organized two deliberative public forums. The first was structured following the National Issues Forum format: facilitated small group discussion informed by an issue guide tailored to the participants, with background data on addiction drawn from the Buford Mills area. Held at the library on a weekend morning, some 25 people were in attendance.

Organizers accustomed to drawing sparse groups to previous public forums on other topics were impressed by the number and by the attention and energy of the participants. “Moms and dads who’d lost a kid,” one organizer reported, “grandparents who were struggling to find money to help a grandchild in recovery, a retired prosecutor, treatment people, law enforcement. These were people really involved in the issue and people really affected by it.” By the end of the three-hour forum, the attendees were motivated for action: “talk, talk, talk,” one said, “we want to do something!” Soon after, the organizers worked with some of the attendees to form an advisory committee to hold a second deliberative forum with the objective of planning strategic community actions.

Two months later, the second event took place, with double the numbers of citizens attending for more than three hours. The city manager and other officials, a former prosecutor, public health agency staff, and a number of families directly affected by opioids were in attendance. This forum was structured as a World Café style event, with four different groups of professionals sitting at their own tables in separate conference rooms. Each group had a 25-minute session in which the professionals passed around prepared materials, made a brief presentation, then opened the floor for a general discussion of three set questions: “What do the professionals do? What else would people like them to do? What can citizens do for the professionals?”

After participating in each of these sessions, all the attendees moved to a large group session to discuss what they had talked about in the small groups and offer reflections on where the community needed to go to deal with its problem. The large group agreed on the goal of establishing a more formally organized county-wide committee for citizens to work on the issue, and seven attendees immediately agreed to serve on the committee.

Reflecting afterwards on the themes emerging from the forums, organizers drew attention to a professional/public divide along four major issues: citizens’ interest in more voice in problem solving; citizen willingness to do something to help; professional overconfidence; and professional reluctance to see citizen perspectives—namely, citizens’ stake in problem framing and problem solving. Comments voiced during the small and large group sessions and written comments collected by the organizers clearly illustrate this divide.

The comments frequently reveal the professionals putting themselves forward as the acting subjects of the story and expecting citizens to be supporting characters to help them with their difficult tasks. One law enforcement official attending the forum, for example, exemplified this standpoint by using a mechanistic analogy: “There are various aspects…There is a treatment aspect of it, there is a law enforcement aspect of it. There may be a spiritual aspect of it. Each one of those, as I see it, if the cylinders are all hitting, the main goal is for it [substance use] to be driven down.”

In the professionals’ narrative, citizens did have significant roles to play in an effective problem-solving division of labor, but these were rooted in the familial private sphere. Professionals commented that citizens should “value spending time with your children above any other events;” “lead by example…[by being] kind to children;” “encourage parent-child bonding, eat dinner together, have game nights;” and “be careful with your meds [by storing] them securely and [turning] in your old meds.”

Yet citizens pushed back against their place in this division of labor and against professional control of the issue. In their comments, citizens wondered: “Can families be empowered to deliver Narcan? What can people do to help users overcome stigma? How can we help kids at school feel welcome and not alone? How can peer-led anti-drug groups be formed in schools? Can we do a community needs assessment with addiction questions included?” Citizens desired to do more than just “stay in our lane” and they challenged the insularity of the professionals’ perspective. Citizens wanted professionals to do something different from being the best police, emergency responders, public health workers they can be on the professional’s own terms; what they wanted is for professionals to work differently with citizens on this problem.

Forum organizers also recognized tensions involved in the citizen/professional divide. One noted that while some professionals came out of the forum with the message that police, emergency responders, and public health workers needed to communicate better to the public about the good work already being done, citizens seemed to want more: namely, the creation of safe and un-stigmatizing public institutions in which citizens themselves had roles to play. “Until we get a handle on the stigma, it doesn’t matter what we do” said a forum attendee whose daughter had died in an overdose just six months earlier. “That’s the thing I heard from my daughter again and again, ‘People hate me. People want me to die.’” Another attendee, whose son had died in an overdose, testified to the confusing patchwork of treatment help available: “I just kept running into so many brick walls.”

Another forum organizer noted a significant amount of professional turf protection: from “tough on crime” law enforcement objections to siting treatment facilities closer to Buford Mills, to public health agency claims that, despite citizen comments on brick walls to the contrary, “we have enough treatment; people just have to be serious about it.” Strikingly, because of the gap between what citizens were saying at the forum about unmet needs and what professionals were claiming about available resources, the Buford Mills city manager reported that she did not know whom to trust. In the weeks following the forum she turned to a citizen-led for-profit recovery organization for advice on how to coordinate efforts.

Your Voice Ohio Forums

The public voices articulated in Buford Mills are no exception. A dozen forums on the opioid epidemic, organized by the Your Voice Ohio public journalism project in late 2017 and early 2018, surfaced similar tensions. Your Voice Ohio forums were held all across the state, with regional news organizations sending journalists to local events and publicizing them to their readerships. More than 500 people participated in these forums, with a demographic makeup estimated by organizers as 50 percent citizens, 30 percent officials and recovery specialists; and 20 percent journalists. As in Buford Mills, organizers involved in the project were surprised by the level of attendance and the energy of the citizens involved.

The two-hour long forums were organized in a World Café format, in which small groups of participants sat around a table to talk, then reported out to the larger group, then changed tables and repeated the process. Each round of table discussions included the following questions: “What do you know about the opioid (or addiction) crisis in your community? What do you think are the causes? What do you think are the solutions?”

For Doug Oplinger, one of the project’s chief organizers, the professional/citizen divide was a prominent overarching theme in the forums. Summarizing his experience in two op-ed essays, he notes that some professionals at the very heart of the issue did not even attend: “Interestingly, in our first two community meetings, doctors and dentists didn’t show up. Elected officials also were in short supply.” Those who did attend were often absent in other ways: “I saw a deep chasm between those crying for help and, in some communities, the people in power—often college-educated and among those who fared better in the deep recession. In fact, there was a tinge of arrogance.”4

Oplinger perceived “a dramatic divide between the terror and desperation in families struggling with opioids and a variety of players who have a role in the crisis—public officials and in particular, the medical industry. Heard over and over in the community meetings was this idea: Every person can gain from participating in conversation with all the stakeholders and thinking about a small role he or she can play in order to make a difference. And meeting participants took note: Doctors and hospitals writing prescriptions for opioids were largely missing from the conversations.”5

A journalist attending three of the forums came to realize professionals were part of the problem they were also desperately trying to solve. Stigma, for example, that kept substance users and their families from seeking assistance, appeared inextricably connected to the ways in which institutions and officials, particularly law enforcement, interacted with citizens. In one forum she attended, the officials were standoffish with the other attendees. The sheriff in a nearby town, taking a tough stance on illegal drug use, had refused to let his officers carry the resuscitation medication naloxone, following a de facto policy of “letting addicts die.”

County officials, mental health and recovery workers, and other professionals at this forum just sat at their “professional table” and refused to circulate. They said, “we have this, we offer that, there’s no problem with access to treatment,” while at a nearby table citizens were bearing painful witness to the road blocks they were facing: “I didn’t see any of that when my brother needed treatment,” said one. “We couldn’t find anything. We couldn’t connect to that.” Such conflicting attitudes, the reporter came to realize, indicated “a real disconnect between the professionals and the citizens in terms of what is out there and available.”

In a report submitted to state policymakers, forum organizers noted stark conclusions:

There is a belief that the crisis is a symptom of far deeper issues in Ohio, with roots in the economy, education and culture of the people and leadership.

There is deep-seated anger and hurt regarding the stigma with addiction, especially as it pertains to opioids.

Arrogance: Media, policy makers and the health care industry must come to grips with the idea that they are no longer trusted. Those professions are different, disconnected, and have not been patient enough to listen.

Citizens are willing to help, the report notes, but find it hard to engage with professionals who see themselves as the primary actors: “People want to help. The most experienced and passionate people are those from families who lost a member to opioids. Who is harnessing this power? Who can guide these families in helping others?” Professionals need to listen more and “engage reflectively in community discussion.” They must recognize that they do not have all the answers and that the problem will not be solved without working with affected communities. “Visit the web site of each county as if you are in a life-and-death situation,” the report urges, “and get an understanding of how difficult it is to find help.”

These are, of course, only snapshots in time, but what is striking about the Buford Mills and Your Voice forums is that even while motivated to come together with each other and with citizens from affected communities, professionals cannot seem to shed traits and tendencies that repel citizen participation in problem solving. While wicked problems may motivate professionals to be more open to teaming up with others like themselves, they still find it difficult to work with citizens. Indeed, wicked problems may generate a kind of defensiveness to protect against conflict (and also against major institutional change). Collaboration yes, but not coproduction.

From Collaboration to Coproduction

As the public forums suggest, and as Rittel and Weber were well aware many years ago, the common-sense collaborative approach to wicked problems is complicated by the history of professional-citizen relations. Humility in the face of complexity and willingness to engage citizens are wise attitudes, to be sure, but professionals must also take sober recognition of three issues: iatrogenesis, prescriptive power, and labeling.

First, professionals have not just failed to solve the opioid crisis but have actually contributed to it through the normal exercise of their specific skills. This is known as iatrogenic harm, inflicted in the course of certified professional treatments such as pain management, criminalization of opioid possession, and insurance coverage that pays for opioids but not physical therapy. (“Iatrogenic” refers to physician-caused harm, but the term is often extended to other professions. Within the legal profession, law-caused harms are sometimes referred to as “critogenic.” Such harms occur in the normal operation of professional work and has nothing to do with “bad apples” among professionals, such as overprescribing doctors or overly punitive police officers.) The consequences of iatrogenic harms among those treated include distrust, fear, isolation, and secrecy.

Second, professionals have a kind of prescriptive power—to dispense drugs, therapies, penalties, and policies—that has accumulated for centuries and is difficult to share. Consequences of asymmetries in prescriptive power between citizens and professionals include community disempowerment, loss of social capital, hopelessness, and the fragmentation of resources as a citizen must see one professional for this part of her problem and another for that part.

Third, professionals have played a major role in labeling not just problems but people who become walking embodiments of problems—the addict, the dealer, the criminal.6 The consequences of labeling include stigma, alienation, and peer reinforcement.

In all these ways, even as they have tried to help, professionals have created institutions that can be incredibly disempowering for citizens. As Beth Macey writes:

[F]amilies operate inside the sizable gaps that have opened up between the two institutions tasked with addressing the opioid epidemic: the criminal justice and health care systems. While shame too often cloaks these gaps in secrecy, some doctors, drug dealers, and pharmaceutical companies continue to profit mightily from them. The addicted work to survive and stave off dopesickness while desperate family members and volunteers work to keep them alive.7

To register the professionals’ own contributions to fostering and exacerbating facets of social problems that make them difficult to resolve, it may help to re-examine the buried assumptions mentioned earlier. The opioid epidemic is not a complicated thing existing in nature, it is a field of failed institutional action in which professionals have held sway for quite some time.

Those aspects of professional relations that mark power over citizens must be addressed straightaway by reform-minded professionals, with a realistic plan for changing professional attitudes and practices, for any genuine doing with citizens to be established. Problem solving is not accomplished by professionals’ punishing, treating, or governing better, more effectively, or in a more closely calibrated way, or by new forms of teamwork, or better service delivery. As one Ohio Emergency Medical Services director notes in a collection of Ohio Opioid narratives, there is “not enough Narcan in the world” to solve this problem.8 Fundamental re-sets in professions and institutions are needed, influenced reflexively by those who have been punished, treated, governed.

Ostrom’s Insights on Coproduction

Collaboration can mean teamwork and cross-disciplinary communication without much more than symbolic attempts to work with citizens. Indeed, symbolic citizen engagement appears to be the public administration default, especially in cases involving under-resourced, marginalized, or norm-breaking citizens.9 Coproduction, by contrast, is where citizens have a co-equal role, as noted by Elinor Ostrom, a chief proponent. Ostrom believed that routine citizen power-sharing is required to effectively provide a wide range of public goods and services. Her research documented and analyzed many cases in which citizens self-organized to solve problems that professionals and state officials had convinced themselves were theirs to handle.

Self-organizing entities are neglected in policymaking and Ostrom’s goal was to bring them forward as real alternatives: “until a theoretical explanation—based on human choice–for self-organized and self-governed enterprises is fully developed and accepted,” she wrote, “major policy decisions will continue to be undertaken with a presumption that individuals cannot organize themselves and always need to be organized by external authorities.”10

Doing for rather than doing with attitudes among public officials are deeply entrenched:

All public goods and services are potentially produced by the regular producer and by those who are frequently referred to as the client. The term “client” is a passive term. Clients are acted upon. Coproduction implies that citizens can play an active role in producing public goods and services of consequence to them.11

Not enough attention has been paid, she thought, “given the gulf perceived between public and private spheres to the problem of relating citizen and official inputs.” Coproduction “requires as much change in the attitude and operational routines of public agencies as it requires input from residents in all phases of the project.” Such culture change began, she believed, from the recognition that coproduction delivered the goods, so to speak, and was “crucial for achieving higher levels of welfare.”12

Ostrom’s case studies showed citizens all over the world engaging in rule making and rule enforcement at high levels of complexity regarding conflict-prone common pool resources such as water or fisheries. She also showed how public services related to education, health, and well-being were being deliberated, creatively produced, and delivered by citizens who had self-organized for that purpose. And while Ostrom was careful to stress that state actors and institutions like judges and courts were highly valuable, on the side, they could also be impediments if they insisted on doing for rather than with. Coproduction, for Ostrom, is not citizens going it alone; nor is not top-down coordination of community involvement by professionals; rather, her ideal is a horizontal playing field in which respect and power are more evenly divided.

What was being coproduced in Ostrom’s cases was nothing short of new institutions. Rules, practices, enforcement procedures were emerging from citizen-led efforts that lead to significant outcomes: sustainable agriculture, fisheries, education, and social order.

This point about institutional change is critical for the opioid case. When an official takes citizens or a citizen organization seriously regarding the coproduction of a public service or good, this entails shifting an institution’s framing of the services, goods, and the various goals they are meant to achieve. In Dayton, for example, “East End, an organization that historically served as an advocate for low-income individuals, helped the police take a more community-centered approach that focused on treating substance misuse instead of criminalizing it.” Coproduction entails exactly this kind of institutional reflexivity: working with and learning from citizens leads to changes in how a public agency’s objectives are named, framed, resourced, and carried out.

Glimpses of Coproduction and Institutional Reflexivity in the Opioid Crisis

Alongside the collaborative partnerships emerging under the epidemic’s pressure are also instances of load-bearing citizen participation in governance work. The least formally organized is the completely citizen-led governance work being done in the private and public spheres. This includes familial care for substance users and former substance users along with care for their dependents. There is also the Samaritan work of resuscitative and emergency treatments like naloxone. Librarians and other community groups have had to lobby for and sometimes protest to share these prescriptive powers of pharmacists and doctors.

Without citizens shouldering these responsibilities in nearly every neighbourhood, the opioid crisis would be far worse. Though it may sometimes appear unorganized and merely personal in motivation—as implied by some of the professionals attending the Buford Mills public forum—what is happening in the private sphere should be understood as governance work. This work includes the painstaking and all too necessary tasks of helping a relative, friend, or neighbour secure resources and connect the dots in a maze of NGOs, public agencies, and for-profit treatment clinics.

More organized governance work, which is still completely citizen-led, is being done by community and activist groups. Needle exchanges, peer support, and therapeutic groups are often initiated and run by those with first-hand knowledge of opioid use. Recovery shelters set up and run by citizens can give a lifeline to substance users lacking family support. While sometimes appearing as simple volunteering, these citizen-led efforts are actually delivering public services and keeping people alive and as healthy as possible. Citizen groups also perform crucial monitoring work, as exemplified by the Your Voice Ohio public journalism project, which gathered important public health information, kept an eye on policymaking, and tracked progress, while making all these resources available on a convenient website.

Opportunities for coproduction have emerged as well in formal government institutions. Specialized drug courts, which predate the opioid epidemic, aim to separate out people charged with drug offenses from other offenders and proceed methodically towards therapeutic treatment rather than penal sanctions. Some have integrated peer support programs, staffed by former users, to help people navigate the criminal justice system and the therapeutic services world while also dealing with the expectations of the surrounding community. As one online resource site suggests: “The focus of long-term peer recovery support goes beyond the reduction or elimination of symptoms to encompass self-actualization, community and civic engagement, and overall wellness.”

Former users have roles to play, too, in rapid response teams made up of law enforcement and public health personnel. They may also be part of wellness check-ups, in which law enforcement teams visit the residences of people who suffered an overdose a few weeks after the event. As one recovering substance user notes, “My experience is preparing me well to help others. Addicts don’t want to have someone just read from a medical book or get advice from some kid with a college degree who’s never been through this. To reach them, they need—they want—someone who has been through addiction and loss. That’s something I can share with people like me, addicts.”13

Coproduction involves a blurring of lines separating professionals from citizens. A librarian may take on a public health or emergency responder task by injecting a patron with naloxone or by retrofitting a library restroom to make sure patrons who nod off in a stall are made accessible to treatment. Likewise, a police officer in a Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative or a judge in a drug court have shifted the boundaries of their roles, taking on more therapeutic and community development skills in the process. And if the citizen staffing a recovery house has moved some distance into the formal realm of governance, probably more than she had ever planned on doing pre-epidemic, so too has the professional working hand and hand with a peer responder moved some distance into the public world of everyday citizens, who are no longer simply voters, constituents, or clients.

Conclusion

One criticism of the perspective taken here is as follows. Shouldn’t criminal justice and public health and government professionals just do their job? Aren’t you adding more work to their already burdened schedules by asking them to work with rather than for citizens? But if I am right about the implications of public forums like Buford Mills and Your Voice Ohio, “just doing their job” is exactly what needs to be reframed and extended. “Doing their job” cannot be coherently understood without including what citizens, both organized and non-organized, have to say about it and about what they can contribute to it. The opioid epidemic has melted away rigid job descriptions and built up increasing pressure for coproductive practices and the institutions fit to foster and house them.

There are specific benefits of the kind of civic agency seen emerging in the opioid epidemic: for former substance users, for professionals, for institutions, and for communities. Trust building is one benefit, but there are many others too: a sense of pride and place among former substance users, educational opportunities for professionals as they work alongside citizens, and the creation of more open and responsive institutions that learn as much as they teach. Coproduction in the opioid epidemic means becoming better able to meet our shared future.

Albert Dzur is a Distinguished Research Professor of Political Science (with a joint appointment in Philosophy) at Bowling Green State University and Contributing Editor, National Civic Review.

1 Rittel, Horst W.J. and Melvin M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4.

2 “Ohio’s experience with opioids has eroded trust to such an extent that we are not always sure which words are appropriate, which are to be trusted, and which are part of an attempt to either evade responsibility or score political points.” Skinner, Daniel and Berkeley Franz (eds). 2019. Not Far from Me: Stories of Opioids and Ohio. Columbus: Trillium, Ohio State University Press.

3 Crowley, Kate and Brian W. Head. 2017. “The Enduring Challenge of ‘Wicked Problems’: Revisiting Rittel and Webber.” Policy Sciences 50.

4 Oplinger, Doug, “What I Heard Ohioans Say About the Opioid Crisis.” Akron Beacon Journal (Feb. 9, 2018).

5 Oplinger, Doug, “Doctors are Seen as Cause, Solution to Crisis.” Wilmington News Journal (April 4, 2018).

6 See Becker, Howard. 1973. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Free Press.

7 Macy, Beth. 2018. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America. NY: Little Brown.

8 Skinner and Franz.

9 See Wagenaar, Henk. 2007. “Governance, Complexity, and Democratic Participation: How Citizens and Public Officials Harness the Complexities of Neighborhood Decline.” The American Review of Public Administration 37 (1).

10 Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

11 Ostrom, Elinor. 1996. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development 24 (6).

12 Ostrom 1996.

13 Skinner and Franz.