By Christian Sigman

What does the highest-ranking appointed public official do when a community issue is raging and getting worse, but the elected office holders do not seem to want to take on the issue and are not experienced in addressing issues that require a multi-disciplinary approach?

As a county administrator and city manager, I was groomed over many years to only help the elected officials form policy, develop and monitor budgets, and keep the trains running on time. We avoid advancing a personal agenda or consciously painting elected officials into a corner.

In a county or municipal government, issues are never “solved.” Crime can never be low enough, traffic congestion acceptable, taxes too low, housing sufficiently affordable, or building permits issued fast enough. If these issues were solved, what would candidates for local offices campaign on? However, skyrocketing heroin overdoses and related fatalities seemed to be “acceptable.” As county administrator, I wonder what can I do, if anything, about the human carnage of opioid addiction? Why can’t the elected officials put as much energy and interest in this issue with life-and-death consequences as they do to save taxpayers $12.32 on their annual property tax bills?

Background

In the beginning, an inmate who was just released from jail overdosed on the courthouse plaza, not 50 feet from the jail exit. For a large urban county, this is just another occasional oddity. Then, the demographic composition of the panhandlers downtown became much younger and increasingly female. Perhaps it was just the economy in recession. Then, the morgue occasionally stopped having enough room for the bodies. Then, mothers were finding used intravenous needles near the playground. Then, the billboards hawking Hepatitis-C cures appeared. The state announced that in 2015 drug overdose deaths exceeded traffic fatalities! Who is tying all of this together? It was the emergency room doctors, first responders, and the media.

The hospitals, especially just across the border in Kentucky, were sounding the alarm. In one hospital system alone, the numbers were surprising. In 2011, St. Elizabeth Healthcare saw a total of 252 heroin overdoses across its six facilities. By 2016, the number had increased to 1,584. Northern Kentucky was one-third the population of my county, but nobody was putting the pieces together.

As county administrator, I had the good fortune to meet leaders and stakeholders across many sectors, professions, and political parties. When a wide swath of these folks is saying they have employees, friends, and family members overdosing, and employer health insurance costs are skyrocketing due to opioid addiction, something is definitely not right. But who will frame the issue for action – any action – for an urban county of 800,000 people?1

I quietly started discussions with leaders in the addiction services business, the sources of the media reporting, the community groups self-organizing in our county and in the neighboring counties and cities; law enforcement officials, and first responders. I asked them about the cause, magnitude, the solutions available, the impact on service providers and responders, etc. These conversations reinforced the notion that a serious public policy issue lurked in the shadows that nobody wanted to own.

What to Do?

If the elected officials do not listen to their appointed professional administrative leaders or the impassioned pleas of a mother who lost a teenage child to opioid addiction, who will they listen to?

I initially thought of moral persuasion from the faith-based community. My first stop was an acquaintance in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Fortunately, the archdiocese covered multiple counties and carried the mantle of social justice and moral authority for a large segment of the population…voters. Turns out the Catholic Conference of Ohio had already issued a policy statement, “Prescription Drug and Heroin Addiction in Ohio.” Once again, the issue was staring me in the face, but the local governments seemed oblivious or purposely looking in another direction. The policy statement from the Catholic Conference of Ohio had three key messages: Talk About It, Get Treatment, and Get Involved. This approach profoundly spoke to me that, as the largest political subdivision in the entire metropolitan area of 2.1 million people, my county had to provide the leadership on this issue.

I spoke to some confidants, and they encouraged me to think of approaching the opioid crisis as a “collective impact” problem to solve. I had never heard of collective impact. Collective impact is a framework to tackle deeply entrenched and complex social problems. It is an innovative and structured approach to making collaboration work across government, business, philanthropy, non-profit organizations and citizens to achieve significant and lasting social change.

This framework was perfect because all the different sectors and stakeholders would provide the collective courage to, and cover for, the elected officials to genuinely engage the opioid addiction issue. This was not only county elected officials, but also municipal, township, state, and federal officials.

Opioid addiction is complex, but elements of the response already existed across the region. Among them: groups advocating for additional funding and insurance coverage for treatment services; groups focusing on prevention and education; a group focusing on reducing overdoses and the spread of Hepatitis C and HIV due to needle sharing; a group focusing on enforcement.

Unfortunately, the range of organizational ability, reach, funding, sustainability varied widely from community to community. “Community,” in this case, was not limited by governmental boundaries, but rather embodied by a church, a health center, a treatment services provider, a social service agency, or a group of folks operating a needle exchange program in known hot spots.

Establishing the Next Level Framework

The framework was easy because the non-profit sector was active around the issue already. Supported by Interact for Health, a private health foundation, community leaders from our county had already organized to write a strategic plan “REVERSING THE TIDE: Hamilton County’s Response to the Opioid Epidemic,” released in late 2014. Interact for Health had funded similar strategic plans concerning opioid addiction in other “rim” counties. Most of the plans addressed four areas:

- Treatment

- Prevention

- Reducing Harm

- Supply Reduction

Unfortunately, while the framework was already established, activating the response plans at scale in the public policy arena was much harder. The “stakeholder” group did not include stakeholders that decide budgets, decide priorities with operating departments, or influence collaboration across jurisdictions. There was a good plan, but it needed to become relevant in the policy and funding circles of the county administrative building and city hall.

Not wanting to reinvent the wheel, I adopted this framework. However, how do I bring the groups together for action at scale in a manner where nobody is being told what to do or forced to reallocate precious few resources, but to share a common mission? I needed their passion, reach, connections, credibility, expertise, etc. I needed them to have a collective vision of success.

Treatment: Treatment means different things to people. Treatment of opioid addiction is needed at every stage. This ranges from folks beginning withdrawal in the jail to the folks on maintenance meds stopping by the clinic every day before work. I went down to the Northern Kentucky Med Clinic early in the morning and watched the process and the clients. If you want to understand opioid addiction, just spend 30 minutes at the clinic Friday morning at 5:15 when folks are getting their weekend meds. This for-profit “clinic” will gladly take cash from the afflicted who are trying to avoid the pain of withdrawal. As I sat in the lobby, the process seemed devoid of any next level support or coordination…you are just a number, but only if you can pay.

The county did have several treatment providers, but no mechanism existed to hand off patients from one program to another, or even worse, one state to another. Additionally, public funding to this provider was primarily allocated to other programs, namely alcohol abuse. Convincing policy makers to fund treatment programs in the jail was hard enough, so asking for funding to help folks after they leave the jail was, at first, a non-starter.

Consequently, the strategy was to get the entire framework established, show some good results in other areas and then make the push for additional treatment funding. Once we could show structure and activity in the areas of law enforcement and first-responder support, then it would be, in theory, safer to ask for treatment funding. While treatment services still receive inadequate funding, I believe the collective impact approach moved the needle enough to at least have meaningful discussions versus the initial head-bobbing from the elected officials holding the purse strings.

Prevention: This element was probably the easiest because PreventionFIRST! was firmly established as a region-wide entity. PreventionFIRST! had a great model for public education for teen drinking and drug abuse, but the usual consumers (i.e., schools and parents) were not fully aware of the opioid epidemic’s societal reach. The organization’s bread and butter document “Strong Voices, Smart Choices,” a Parent’s Guide: Talking with Kids about Drugs, was out of print. Having PreventionFIRST! at the table was having the most strategically important stakeholder for its mission was the least controversial, its communications reach the cheapest to fund, and its board comprised a group of recognized community leaders.

Reducing Harm: This was also an easy element to tackle, but the one with the biggest political risk. Police officers had to start administering Naloxone “Narcan” (one agency’s union leadership thought this activity was subject to collective bargaining). EMS responders had to accept that revived opioid overdose patients are frequently ungrateful and occasionally overdose again the very same day. Elected officials had to look beyond dogmatic notions that needle exchange programs just enabled addicts. Pharmacists needed to be more emphatic, and everybody needed to look the other way when “good Samaritans” (who are occasionally dealers or enablers) called 9-1-1 for help. The county’s efforts focused on getting Narcan to the first responders across 40+ law enforcement agencies in the county. Additionally, by providing the Narcan, we gained an insight into actual usage and better understanding of the issue at the street level.

Reducing Harm: This was also an easy element to tackle, but the one with the biggest political risk. Police officers had to start administering Naloxone “Narcan” (one agency’s union leadership thought this activity was subject to collective bargaining). EMS responders had to accept that revived opioid overdose patients are frequently ungrateful and occasionally overdose again the very same day. Elected officials had to look beyond dogmatic notions that needle exchange programs just enabled addicts. Pharmacists needed to be more emphatic, and everybody needed to look the other way when “good Samaritans” (who are occasionally dealers or enablers) called 9-1-1 for help. The county’s efforts focused on getting Narcan to the first responders across 40+ law enforcement agencies in the county. Additionally, by providing the Narcan, we gained an insight into actual usage and better understanding of the issue at the street level.

All was not easy, though. Certain cities and townships did not want to take the free Narcan or have needle exchanges in their community. As of this writing, Narcan is a staple of most public safety responders without question, and resistance to needle exchanges appears to be weakening.

Supply Reduction: This element was merely a logistical issue as the inter-agency relationships already existed. The county provided the space for the investigators from multiple jurisdictions to work together. We also provided the funding for investigative equipment and computers. For a large urban county, these were relatively easy to provide. The police chief from one of the smallest communities in the region had already pulled together a small group of investigators through the county police chiefs’ association. His energy and passion were infectious; his team just needed space, equipment, etc. He was the empathic human face, and the only public official trying to address opioid addiction long before it was fashionable for elected officials to adopt the cause. This group of investigators did a deep dive into every overdose fatality to identify the source of the drugs.

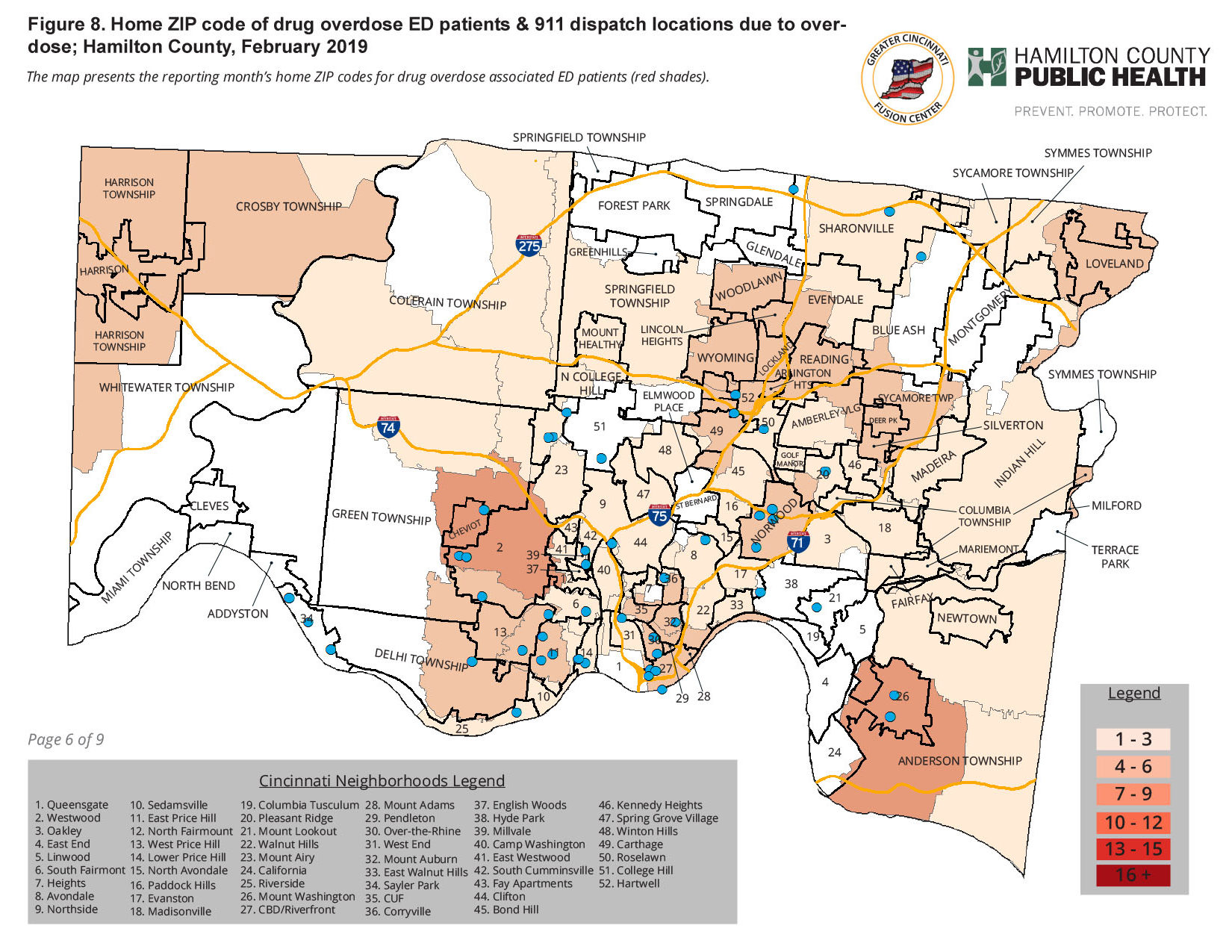

One of our biggest successes was the implementation of a county-wide GIS tracking system for all incidents involving opioid addiction and drug activity across 40 plus police departments and 400 square miles. Since the county provided the wireless data system for these agencies, adding an icon to the mobile data computers to document an overdose call, a found used syringe, etc. created a vast amount of information for the investigators.

Forming the Coalition

The framework was instrumental in determining the membership of the Hamilton County Heroin Coalition. Once again, many of the same stakeholders were asked to join the coalition, but HCHC was established for action, not study.

If the coalition wanted to be action-oriented, the decision-making process and meetings needed to be structured to facilitate action. For example:

- Notify coalition members of actions that were being studied and implemented while seeking advice and counsel, but not unanimous permission. This approach requires a lot of pre-meeting communications, so members are ready at the meeting. It is also possible to be less formal when there is trust in the professional judgment and leadership of the steering committee members.

- Implement efforts with notice only. Meetings were initially 3-4 months apart, so many efforts were just implemented with notice to the coalition members.

- Bill the initial efforts as pilots with the intent to ask for larger sums when the next property tax levy cycle came around.

- Encourage and support self-initiated responses. For example, one township developed quick response team (QRT) to follow-up on every overdose call. The coalition supported the township’s efforts publicly and prioritized Narcan distribution to this community. This program has subsequently expanded to multiple teams across the county.

- Pre-sell next steps for 6-9 months out. For example, I overtly mentioned at every meeting that the pilot efforts were building up too much larger budget investments.

- Be careful not to distinguish the county from any other city, township, or village as well as not distinguish between public entities and the nonprofit service provides. It was a team effort and unified voice. A county versus city dynamic would have derailed the entire effort. In this case, some city officials realized they were late to the party and tried to hijack the effort.

Changing the Narrative: Inject Hope

The framework was formalized, the coalition and institutional roles established, incremental funding secured, but the issue was still in the shadows of the community. The public sector’s response was gaining steam, but the community had not come together on the issue.

The public narrative concerning opioid addiction needed to evolve from fear and dogma to action and hope. It was no different than the evolution of AIDS / HIV as a public health issue.

Once we were all in on the collective impact approach, we needed a message / image / brand for the effort. We wanted Smoky the Bear or McGruff the Crime Dog. We did not want “This is your brain on drugs.”

Fortunately, Cincinnati probably has the world’s highest concentration of brand consulting and product design companies due to the global headquarters of Proctor and Gamble (P&G). One of the companies supporting P&G is Landor (think Pringles or Tide). Landor had recently helped a county-wide ballot campaign for the $225 million renovation of the historic Union Terminal. Landor created the slogan “Save our Icons” for the public campaign, which can be found online. It was simple, catchy, and cute.

I sought out the local Landor leader and scheduled a meeting. I approached it very carefully, as a company with clients like P&G may not want to be associated with the opioid crisis. To my pleasant surprise, I found a company that threw its entire creative talent into the effort. I know what companies pay for this type of brand consulting, so I will be forever grateful for the contributions from Landor. The resulting “brand” to change the narrative on opioid addiction was Inject Hope.

Please visit this link for additional background.

This campaign became Landor’s most awarded pro-bono project globally. It was a finalist at Fast Company’s 2017 World Changing Ideas Awards and chosen to appear in Communications Arts magazine.

The Inject Hope “brand” was used to develop an umbrella for regional messaging, centralized access to how to get involved, get help, and more. Inject Hope brought the regional collective impact approach to its full potential.

Growing Pains

The aforementioned activities covered an 18-month period in 2015 and 2016. A framework was developed and lots of big-hearted people were willing to help, but barriers were identified, and lessons were learned. For example, who is at the table? Once the effort received media attention, everybody wanted in. Those who wanted to get involved included some of the very elected officials who dogmatically opposed offering needle exchanges or providing Narcan to persons without a prescription.

We learned that wording and imagery were important. I did not know that the image of a needle was actually a trigger for some addicted persons. Subsequently, the needle image was dropped and “Inject Hope” was slowly phased out. I did not appreciate how hard it was going to be to get treatment providers and other counties to use a single platform that would enable people in need to get information across the entire tri-state region. It is not uncommon for a loved one to live in a different state, county, or city from the person needing help.

I did not recognize that interest by some elected officials was situational. Once the election was over, or the pressure from a higher-ranking party member waned, or when leadership decisions to provide meaningful funding for treatment services was needed, some elected officials were just content with pointing to the Inject Hope logo as the government’s coordinated and purposeful response to opioid addiction.

Results

Addressing opioid addiction has matured from an issue to be avoided politically to one that is firmly established as a top priority public health issue (not a crime issue as crack cocaine response was framed in the 1990s). First responders, treatment providers, and medical professional were bought together by Interact for Health to develop a response plan. The response plan was adopted into a collective impact effort facilitated by the county administration to bring it to scale, to sustain a level of effort both fiscally and politically and change the narrative.

The Hamilton County Heroin Coalition is still guided by a small steering committee of nine, but a coalition member organization now exceeds 50. The steering committee meets monthly and has a grant-funded program officer. Goals and results are published regularly. As of February 6, 2018:

- 900 pounds of prescription drug were collected at “Take-Back” boxes.

- A 16-bed engagement center was established to assess, divert, triage overdose patients after an emergency room visit

- 2,000 Narcan doses are distributed monthly across 40+ law enforcement jurisdictions

- Every overdose is tracked and investigated

All these efforts, and much more, were accomplished by collaborating in a different way and fostering partnerships for collective impact.

Perceptions of opioid addiction have changed across the entire community. Institutions work more closely together. Some additional funding was provided for treatment services, but not nearly enough.

Prologue

The heroin coalition’s formation did not consciously follow the collective impact framework, but the shared goals, a dedicated core steering committee, and consistent and open communication were key elements of the effort. The collective impact approach is gaining traction in local government, but the approach is firmly rooted in the nonprofit sector. The National Council of Non-profits provides an excellent resource to learn about developing a collective impact approach as well as evaluating the success of the collective impact approach.2

As county administrator, I should not be credited with any of the results of the Hamilton County Heroin Coalition. It was a team effort of many much more capable leaders in the community. I would like to think that I just helped them come together a little faster and more openly.

I have since relocated to Brookhaven, Georgia. I used this same collaborative approach for an affordable housing task force in my new city. Again, the city manager does not push a personal agenda, but utilizing the position to galvanize existing resources and stakeholders to reach a shared vison for success can move the needle on complex community problems.

Christian Sigman is City Manager of Brookhaven, Georgia, and a Richard S. Childs Fellow.

12015 Ohio Drug Overdose Data: General Findings, Ohio Department of Public Health

2 www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools-resoruces/collect-impact