By Jared Ross

In the past ten years pedestrian deaths have risen by 75 percent,1 and, while they have fared better, cyclist fatalities are not far behind. Larger and more powerful vehicles, bad road design, and even increasing ideological and political division have contributed to this problem. Though city officials are not able to address things like vehicle design standards directly, they can design and implement streets that mitigate the hazards posed by larger vehicles, and they can implement zoning and subdivision standards that lead to safer forms of development.

In the past ten years pedestrian deaths have risen by 75 percent,1 and, while they have fared better, cyclist fatalities are not far behind. Larger and more powerful vehicles, bad road design, and even increasing ideological and political division have contributed to this problem. Though city officials are not able to address things like vehicle design standards directly, they can design and implement streets that mitigate the hazards posed by larger vehicles, and they can implement zoning and subdivision standards that lead to safer forms of development.

Though pedestrian and cyclist deaths have increased in almost all municipalities nationwide, some have increased at a much lower rate than the national average. It is difficult to isolate a single reason for a particular community’s success, but many of these stand-out cities have put forth policy and funding efforts focused on implementing evidence-based treatments, elements, and features. Some of the data focuses solely on pedestrians or cyclists but both share many of the same safety issues and therefore have similar safety solutions. I term both biking and walking as “active” modes of transportation throughout this article and what I say about either biking or walking can generally apply to both.

Problems to Overcome

Policy makers tend to place greater economic value on the time drivers spend driving than the time pedestrians spend walking. This tendency leads to policies that prioritize the wants and needs of drivers over the preferences and safety of those that partake in active transportation. The way we track statistics on automobile accidents involving pedestrians or bicycles further undermines the problem. In such an accident, the non-driving party is more likely to be incapacitated and therefore unable to recount their side of the story. Furthermore, when someone dies from medical complications days after an accident, it is unlikely the official cause of death will mention an impact with a motor vehicle—instead something like “internal bleeding” may be all that is recorded.

Policy makers tend to place greater economic value on the time drivers spend driving than the time pedestrians spend walking. This tendency leads to policies that prioritize the wants and needs of drivers over the preferences and safety of those that partake in active transportation. The way we track statistics on automobile accidents involving pedestrians or bicycles further undermines the problem. In such an accident, the non-driving party is more likely to be incapacitated and therefore unable to recount their side of the story. Furthermore, when someone dies from medical complications days after an accident, it is unlikely the official cause of death will mention an impact with a motor vehicle—instead something like “internal bleeding” may be all that is recorded.

A lack of density can be a major impediment to active transit. Many commuters who do not bike list the distance of their commute as a major reason why they drive instead. Single use zoning that does not allow for more compact development is a major roadblock to active travel. Along with that, many cities require too many parking spaces in new developments. Excess parking encroaches on the space needed for active transportation facilities and discourages compact development (density). Dedicating more space to automobiles encourages people to drive instead of walking or biking, and this lack of density increases travel distance, making active travel less convenient. In turn, this reduces the number of people who bike or walk in a community making active transit more dangerous.

Safety Solutions: Physical Treatments

Most treatments in the built environment involve an element that separates vehicles from active travelers in time and/or space. Traffic lights for bicycles provide a separation in time between when bikes and cars can occupy an intersection. Buffered bike lanes provide a physical gap of space between bicyclists and drivers and separated bike lanes incorporate this space separation and add a physical barrier.

Most treatments in the built environment involve an element that separates vehicles from active travelers in time and/or space. Traffic lights for bicycles provide a separation in time between when bikes and cars can occupy an intersection. Buffered bike lanes provide a physical gap of space between bicyclists and drivers and separated bike lanes incorporate this space separation and add a physical barrier.

The particulars of a physical treatment can affect its safety. If a separated bike lane places cyclists too far away from an automobile drive lane, drivers making right turns are less likely to see cyclists traveling straight. While this increased separation may make cyclists feel safer because they are further away from automobiles, this sense of safety is misleading.

Many safety elements may be at odds with perceived interests of automobile drivers.

For instance, departments of transportation will often remove large trees if they deem them too close to a road, assuming that the trees pose a safety hazard for drivers. But trees alongside a roadway slow traffic speeds and provide separation for cyclists and pedestrians. Even though these trees may pose a risk to drivers who veer off the road, their speed-reducing quality may increase safety for all other drivers anyway. Many design choices that reduce the total number of accidents between automobiles on a roadway may increase the number of fatal accidents. This dynamic is often more pronounced when examining accidents between an automobile driver and an active transit user.

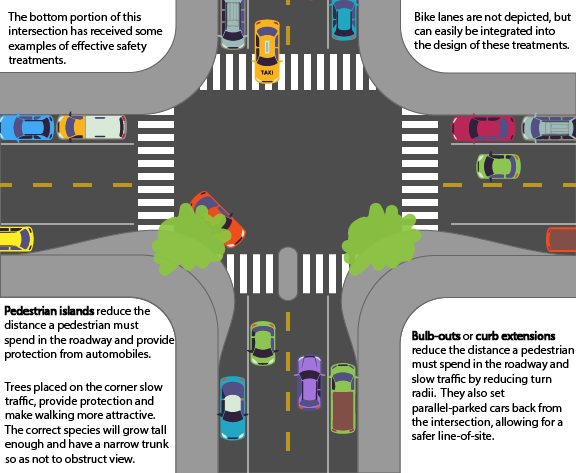

Many features that help pedestrians feel more comfortable and increase their safety also slow speeding vehicles. Curb extensions that bulb out and pedestrian islands both reduce the distance a pedestrian must travel to cross the road, but they also narrow the drive lane and therefore reduce vehicle speeds. Features that reduce vehicle speeds are far more effective at ensuring vehicles drive at safer speeds than simply lowering the speed limit with a sign that drivers often ignore.

Provided they don’t hurt safety outcomes, efforts to make active travelers feel safer can often indirectly increase actual safety. When cyclists and pedestrians feel safer, they are more likely to walk or bike more often. The safety in numbers concept holds that if more people engage in active transportation, their safety outcomes improve per capita. The more cyclists or pedestrians there are, the safer they all become. Safety in Numbers is one reason why less dense development is bad for active transit safety.

There are also physical elements that may not directly address real or perceived safety issues but encourage greater pedestrian activity. The presence of trees or certain building design standards have been shown to increase pedestrian activity in a particular area. Zoning and subdivision regulations that encourage compact, mixed-use development and building design elements such as ground-level, street-facing window requirements lead to increased pedestrian activity.

Safety Solutions: Urban Form

Wide drive lanes and fewer intersections may mean smoother traffic flow, faster driving speeds and fewer fender-benders, but it is precisely this unobstructed traffic flow that makes a road more deadly.2 Planners have found that neighborhoods with wider, curvilinear and cul-de-sac street designs lead to worse street safety outcomes than older, grid-like streets with stop signs at every intersection.3 Wide, curved streets mean that when a toy inevitably escapes the safety of the driveway, a pursuing child is less likely to be noticed.

Cul-de-sacs may seem as though they limit traffic and keep non-residents out of the neighborhood, but they prohibit better street connectivity, which means that people must travel farther on less direct routes to get to their destinations. Arterials are larger, faster through-streets, designed to carry high volumes of traffic for longer distances. They are the most fatal road type in our transportation infrastructure and are often used to compensate for the loss of efficiency created by poorly designed, sprawling neighborhoods with bad connectivity. A house on a cul-de-sac may be a safer option if the residents never leave the neighborhood, though even that is debatable.

Cul-de-sacs may seem as though they limit traffic and keep non-residents out of the neighborhood, but they prohibit better street connectivity, which means that people must travel farther on less direct routes to get to their destinations. Arterials are larger, faster through-streets, designed to carry high volumes of traffic for longer distances. They are the most fatal road type in our transportation infrastructure and are often used to compensate for the loss of efficiency created by poorly designed, sprawling neighborhoods with bad connectivity. A house on a cul-de-sac may be a safer option if the residents never leave the neighborhood, though even that is debatable.

It is no coincidence that many of the gridded neighborhoods were built during a time when the automobile was not the central focus of city design. Narrow streets make drivers less comfortable driving at excessive speeds and make them pay closer attention to their surroundings. Straight streets give drivers better line-of-sight to see activity along the side of the road.

Some cities are removing arterials and reaping the rewards. The City of Milwaukee removed a large spur of the Park East Highway that was dividing neighborhoods in its downtown and successfully redeveloped the area. There was strong apprehension in the community over this decision, with citizens speculating it would hurt the city, but this removal led to economic prosperity for the area and increased property values. Syracuse, New York, is just the latest municipality to remove a major highway and restore a grid street design to a neighborhood. While it is difficult to change an existing street pattern, projects like these prove it is possible.

More dense neighborhoods have higher rates of cyclist commuters, so policies that lead to moderate building density accompanied by mixed land use are an effective way to increase pedestrian rates. Street type, building type and building density all work together to raise rates of pedestrians. Sixteen dwelling units per acre is the threshold where neighborhoods become walkable, local businesses are supported, and transit is supported and viable.4 Few areas of American cities reach this level of density, and it would be unreasonable to expect cities in their entirety to meet this threshold. Density is just part of the equation when figuring out what makes a neighborhood walkable; often allowing for a mixture of land uses in or near neighborhoods and encouraging commercial and employment uses can be even more important.

A city’s subdivision regulations and zoning code can ensure development takes a more desirable form. Many cities are reducing or eliminating minimum parking requirements. Subdivision regulations should require active transit facilities or certain levels of density. Zoning codes should allow mixed-use development, and cities should employ methods to financially incentivize commercial and employment centers that are dispersed throughout their boundaries.

Safety Solutions: Education and Information

People must know active transit facilities or features exist and how to use them or these efforts will go to waste. One of the best ways to help cyclists feel more comfortable and to increase their level of safety is through informational programs. For example, Fort Collins, Colorado, has a local Bike Map with color-coded, low stress routes. It also contains extensive safety information and infographics on how infrastructure, street markings, street signs and intersections are designed to operate. Fort Collins also has a Bike Skills Hub with full scale examples of bike facility infrastructure where riders can practice the safe riding techniques mentioned in the handout. City employees often have tables at non-planning events to inform potential cyclists of existing facilities and help them feel more comfortable to take up biking as a form of transportation in the city.

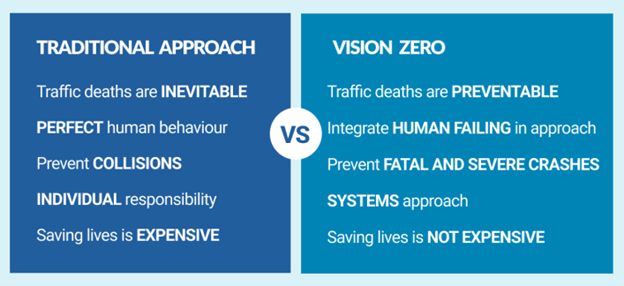

Vision Zero

Vision Zero is an international effort to reform the way we think about traffic fatalities and the way municipalities respond to these fatalities. The Vision Zero philosophy supposes it is possible to eliminate all traffic deaths. It is an effort to move the status quo away from assuming that some traffic deaths are inevitable. The idea is that as long as there are any traffic deaths, a municipality should consistently make efforts to improve safety. Many municipalities have fully adopted Vision Zero, while others have incorporated the philosophy into some of their policies. Vision Zero, as a non-profit organization, certifies cities that have made enough of an effort to fit their criteria, and they provide resources for cities that wish to reduce traffic deaths.

Source: https://visionzeronetwork.org

An Example

As it happens, Minneapolis is a certified Vision Zero Community. I spoke with two city staff members, Alex Schieferdecker, Pedestrian and Bicycle Coordinator, and Burruss Fontaine, Senior Transportation Planner, to learn about what the city has been doing to address active transportation safety. Minneapolis has seen increased safety outcomes as the city re-works its street infrastructure. Since much of the city was developed around streetcars, street layout and design tend to be friendly to active forms of transit. This provides more space than older city layouts while avoiding the sprawl created by automobile-oriented cities of the 1950s. Minneapolis has been successful in planning and street design for active travel, in part because the city has not experienced any major booms or busts, which means that neighborhoods were planned on a smaller scale and when there is a national real estate crash, large portions of the city are less likely to be left vacant. In Minneapolis, student housing was built earlier on in the more recent wave of development. This provided a good functional example of substantial growth without adding many parking spaces, which helped alleviate potential parking concerns from the public moving forward. Minneapolis has a great park system, encompassing many of its lakes. Much of the city was built during the railroad boom and now many of the old railways have been converted into multi-use paths connecting many of these parks.

The city has used these circumstances to their advantage and aggressively developed a robust network of separated bike lanes as they replace streets in need of repair. Their design standards dictate building a raised bike lane along any street that gets reconstructed. Alex and Burruss felt confident they had the tools to virtually eliminate pedestrian and cyclist deaths, despite many circumstances outside of their control.

Conclusions

Just about everyone will inevitably become a pedestrian at some point. Once they park their truck, hybrid, or bicycle, every citizen will resort to walking on the way to the entrance of their destination. Vehicle size, weight and power have all increased over time and these are certainly contributing factors to the increase in active transit deaths. Planners and policymakers still have plenty of agency over the matter; they simply must incorporate urban design and policy that prioritizes traffic calming and the needs of more vulnerable travelers. Efforts to reform vehicle design could be beneficial in reducing fatalities, but national policies are much more difficult to change.

Jared Ross is a recent graduate of the University of Colorado Denver where he received a dual Master of Public Administration and Master of Urban and Regional Planning degree. His background is in community organizing and sustainable policy.