By Wendy Schaetzel Lesko

We are all painfully aware of the deep feelings of disillusionment and distrust that many members of the public—especially young Americans—hold when it comes to democratic institutions. So, it is more important than ever to invite rising generations to participate in local government, but the oft-repeated phrase, “children are the leaders of tomorrow,” sends the wrong message. It tells young people to wait their turn. Delayed, token, or selective engagement with this critical demographic risks disengagement well into young adulthood and beyond.

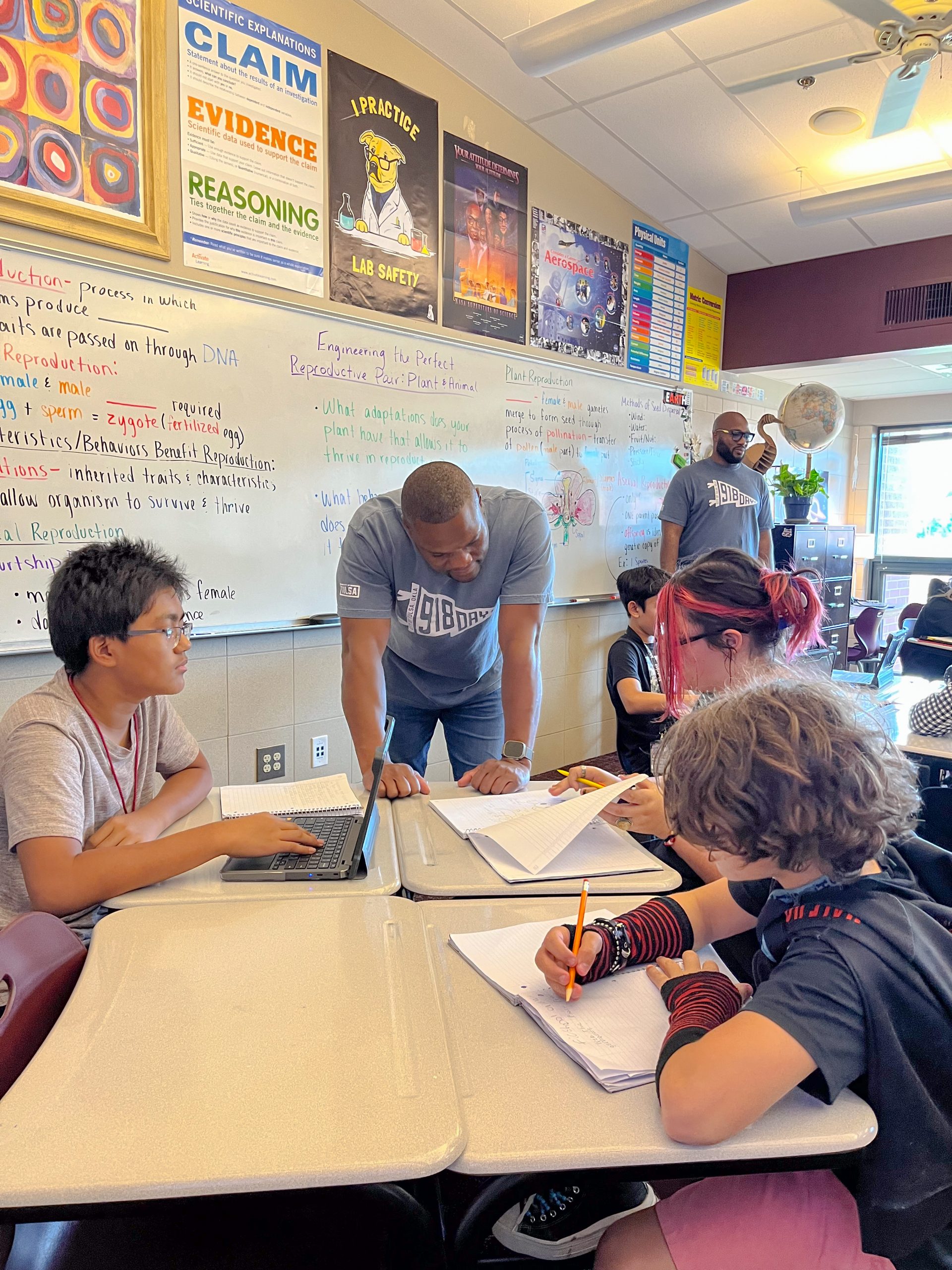

Local governments should be offering multiple opportunities for civic engagement during formative years. Although negative stereotypes about teens persist, their non-expert expertise is irreplaceable. This article highlights promising practices and examples, drawn from my two decades of work supporting aspiring teen problem solvers in the public policy arena. Visionary government leaders are building more “on-ramps” for citizen involvement that actually listen and hear “youth voices.”

Core Commitments

The biggest hurdle is convincing elected officials and their staff that those under age 18 have much to contribute. Years ago, the head of the Oregon Commission on Children and Families called for an “adult attitude adjustment.” Basic commitments set the stage for meaningful and sustained youth civic engagement:

- Support from the top. The mayor or city council champions youth integration as a core principle.

- Dedicated resources. Funding is secured for training, implementation, and evaluation.

- Presume competence. Knowledge is respected regardless of age or background.

- Team design. Young people co-create action plans for engaging their peers.

- Inclusive recruitment. Outreach intentionally attracts those most impacted and furthest from power.

- Seek unconventional thinking. Bold or imaginative ideas are met with curiosity, not dismissal.

- Compensation. Young people are valued through stipends for their time and talent.

- Extra support. Staff working directly with youth are recognized and compensated.

- Flexible scheduling. Meetings accommodate school and other responsibilities, often early weekday evenings.

- Frequent communication. One-to-one check-ins and interdepartmental collaboration are prioritized.

- Jargon-free language. A balanced information exchange is encouraged between youths and professionals.

- Feedback loops. Decision-making processes are transparent and inclusive.

- Adult-youth equity. Organizational policies maximize participation through shared power.

- Adaptation. Continuous experimentation refines practices for sustained and expanded inclusion.

- Affirmation. Cities are the laboratories for the country, so it is vital to share the innovations and impacts of youth engagement.

Intergenerational Interactions as the Norm

The invitation for youth perspectives can catalyze a lifelong habit of civic participation. Often, one activity plants the seed. Multiple entry points increase the odds of sustained involvement.

Take Jayzen Cruz, who recalls being “very shy and withdrawn.” Encouraged by his brother, he joined a subgroup of the Mayor’s “Youth Voice, One Vision” at his local rec center in Rochester, New York. Soon he spoke publicly during the city’s $200,000 participatory budgeting project. He then contributed ideas to the city’s 15-year comprehensive plan. By 16, Jayzen held a part-time position in workforce development—proof that early opportunities can reshape trajectories.

Young people serving on city commissions represent another entry point. Transportation is one issue that motivates City of Woodbury, Minnesota, to seek out the voices of those with different experiences and insights. High school junior Daniel Song, who served on the planning commission, says he appreciates, “learning from my fellow commissioners who are so knowledgeable, and the city council takes our feedback super seriously and some of our amendments and proposals are actually added to the final plan.”

Two young representatives in Rochester Hills, Michigan, sit on every advisory committee including liquor licenses, public safety, water quality and even cemeteries.

The city of Hampton, Virginia, has employed two youth city planners since the 1990s. These high school students work part-time, seeking feedback not only from the youth commission but also from community groups. Their listening sessions led to a design revamp of a $30 million facility for competitive swimming teams. This 2022 AquaPlex provides recreational features and swim lessons for all second graders. In the words of Terry O’Neill, who served as chief city planner for decades, “Young people are an equal part of the conversation that led to a whole number of decisions that made a far better investment of the city’s dollars than what we were originally thinking.”

Regular interactions with younger minds, formal and informal, can oxygenate the thinking of experts and professionals alike.

Invest in Critical Coaching

Young people often wrestle with imposter syndrome. Kyla Reed, a Hampton youth city planner, recalls: “When I first started at 16, I felt so awkward sitting in a room full of people who had been to college and were doing amazing things. But they really tried their hardest to make us feel like regular city planners with just as much input as they had.”

Overcoming intimidation and unlocking youth potential depends heavily on supervisors. Confidence and trust are built through a careful balance of encouraging ambitious ideas while setting realistic expectations about things such as the slow pace of policymaking processes and constraints such as state preemption.

Turnover also creates challenges—among both young participants and lower-level staff often tasked with managing youth initiatives. Contracting with a non-profit community organization with a track record of collaborating with young people can make an enormous difference. These professionals bring special skills in facilitation, training, and civic processes such as drafting legislation or reviewing grant applications.

Tulsa Changemakers in Oklahoma serves as the official partner with the city council and the Department of Resilience and Equity. This close coordination resulted in the youth council interviewing over 150 people across Tulsa and holding meetings with city employees, which resulted in generating five proposals, including addressing a shortage of school bus drivers and developing a peer-led driver safety curriculum.

Tulsa Changemakers in Oklahoma serves as the official partner with the city council and the Department of Resilience and Equity. This close coordination resulted in the youth council interviewing over 150 people across Tulsa and holding meetings with city employees, which resulted in generating five proposals, including addressing a shortage of school bus drivers and developing a peer-led driver safety curriculum.

Two staff-members in the young adult department of the San José Public Library coordinate the city’s 11-member youth commission and also collaborate with 50 more teens who participate in hyper-local youth advisory councils that initiate their own proposals, for example, a juvenile diversion program.

Shift from Volunteer to Paid

More cities now realize that recognition alone is not enough. Pizza and gift cards no longer suffice. “Compensation is now a given,” says Carina Lieu, Inclusive Community Engagement Officer in Oakland, California. “School is a young person’s full-time job, and many have family responsibilities. They are paid for their valuable expertise and moral authority, usually $25/hour.”

In San Jose, California, youth commissioners spent months drafting a proposal to broaden representation. The city council unanimously approved this change to the municipal code providing a stipend of $200/month for future commissioners designed to attract diverse participants by those who cannot afford to volunteer.

While many youth leadership initiatives in city government remain volunteer-based, providing compensation and/or other incentives is increasingly becoming the norm.

Building New Pathways for Youth Inclusion

Despite clear progress, pathways for meaningful youth participation remain limited. Long-established youth commissions are evolving but too often remain symbolic. It is up to elected leaders to go further, engaging young people not only in planning events and identifying issues but also engaging in deliberations over controversial issues ranging from curfews to extending voting rights to 16- and 17-year-olds.

As Addie Lentzner, a youth leader advocating for expanded shelter services, reminds us: “There is an entire community that makes up our world that is not being accurately included due to our internalized biases about what they are capable of. It is up to all of us to design organizations and structures WITH young people for the benefit of ALL.”

Her words are a clarion call. Token gestures are no longer enough. Cities that succeed in this work are those willing to open the door wide—to see young people not as future assets, but as present-day partners with imagination, urgency, and moral authority.

The next chapter of civic renewal depends on it. To overcome disillusionment and distrust in our democracy, we must harness the talent of the rising generations right now. Genuine youth infusion is not a side project or photo op. It is a necessity if we are to rebuild trust, strengthen communities, and design solutions that reflect the full wisdom of every generation.

Wendy Schaetzel Lesko covered the US Congress for print and radio, co-founded the Youth Activism Project and most recently coauthored with 19-year-old Denise Webb “Why Aren’t We Doing This! Collaborating with Minors in Major Ways.”