By Nick Vlahos

Introduction

For more than a century, the council-manager form of government has been the gold standard of ethical, professional, and efficient municipal administration. Championed by the National Civic League (NCL) and codified in its Model City Charter, this form emerged from the Progressive Era’s push to depoliticize local government and restore public trust. Yet, as the League’s Ninth Edition of the Model City Charter (2021) underscores, the landscape of civic governance has changed. The 100-plus-year history of the League is attributed to the core governance challenge of modernizing and innovating government and, by association, democracy. At the time, in the mid-to-late nineteenth century and even into the early twentieth century, various pressures related to clientelism and patronage required new mechanisms for accountable decision-making.

Contemporarily, there are mounting twenty-first century pressures and challenges related to democratic deficits, all of which call for specific reforms to facets of existing governance models. Public confidence in government is fragile. Surveys by the Pew Research Center and others show historically low trust in national institutions. Elected officials repeatedly face hostile public attitudes and treatment. At the same time, residents increasingly expect transparency, dialogue, and responsiveness, beyond efficient service delivery. Despite the sometimes very good, concerted efforts of local governments to crowdsource public input, public engagement efforts generally lack teeth and a consistent, visible throughline from ideas to implementation. In other words, the formal integration of public decision-making is missing from modern models of governance.

The events of the past decade, from racial equity movements to pandemic response disparities, have placed diversity at the forefront of local governance. Cities are no longer judged solely on how well they manage budgets or deliver services, but on how fairly and inclusively they do so. The Ninth Edition of NCL’s Model City Charter explicitly frames equity and engagement as core governance principles, calling on cities to embed them in their charters and practices. In this article, I propose taking this a step further to define some of the structural components of advocacy for more “engagement.”

Indeed, there are plenty of exemplary individual practices to draw from, but not necessarily a comprehensive system of overlapping processes that overlays with and replaces outdated facets of traditional models of government policy-making and implementation. The past twenty years have seen a quiet revolution in democratic innovation: Participatory budgeting (PB), pioneered in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and now practiced in various U.S. cities, invites residents to decide directly on portions of municipal budgets. Studies show PB enhances trust and civic knowledge. Citizens’ assemblies and juries, used widely in Europe and increasingly in the U.S., e.g., Petaluma, California (2022), Deschutes County, Oregon (2024), Fort Collins and Boulder, Colorado (2025), and Raleigh, North Carolina (2026), demonstrate how deliberative processes can yield legitimate, informed recommendations. Digital co-governance platforms, such as Barcelona’s open-source Decidim, allow residents to track, propose, and co-design policies transparently, asynchronously, and digitally.

Alongside traditional government and public service delivery professionalism, residents now expect equity, inclusion, and meaningful participation to be pillars of local democracy. This evolving context opens the door to a Resident-Model of Government. The field has been pushing to make participation legal, but the next step in the evolution of thinking about how to embed public decision-making could be to make it a new model of governance. This model would be added to the council–manager and mayor-council systems of government where they exist in different cities, but reimagine residents as co-governors, not merely constituents. This new model would embed formal, charter-level mechanisms for resident collaboration directly into municipal governance.

Council-Managers and Mayor-Councils in Perspective

The council-manager form of government was born in the early 20th century out of frustration with corrupt, patronage-driven political machines. Dayton, Ohio, became the first major U.S. city to adopt this system in 1914, appointing a professional city manager to administer operations under the policy direction of an elected council. The idea was simple but revolutionary: politicians should make policy, while trained professionals should run the city. Over time, this model spread rapidly, notably among small- and medium-sized municipalities, becoming synonymous with efficiency, accountability, and ethical stewardship.

In contrast, the mayor-council form retained stronger political leadership. Under a mayor-council system, a directly elected mayor serves as the chief executive, wielding appointment, budgetary, and veto powers. Some argue that this form demonstrates visible, decisive leadership. Authority often rests collectively with the council or is shared with a professional administrator.

Each form reflects a different democratic theory: the council-manager form emphasizes competence, continuity, and insulation from partisanship, and the mayor-council form centers political accountability and decisiveness. Both have served communities in various ways. Yet each form of government has limitations in resident engagement, which have become evident in an era when governance legitimacy increasingly depends on collaboration and public trust rather than on professional hierarchy alone.

The strengths of the council-manager model include professionalism and stability, and it is the League’s model. City managers bring expertise, continuity, and a management focus insulated from electoral cycles. They provide ethical safeguards by separating politics from administration, reducing opportunities for corruption or patronage. They also offer clear accountability lines between council (policy) and manager (execution), enhancing efficiency. That said, this type of professionalism has limitations by inadvertently creating a gulf between government and community; residents often perceive decision-making as technocratic and opaque. In addition, without a singular, charismatic figure, cities sometimes struggle to communicate vision or rally civic energy in moments of crisis. Lastly, most engagement occurs reactively via public hearings, comment periods, or advisory boards rather than as part of governance design.

By contrast, it is sometimes argued that the mayor-council model entails unified leadership that enables swift decision-making and coordination across departments, as well as public accountability, since voters know who to credit or blame for city performance. However, the limitations of this model include the risk of politicization of appointments, and limited checks and balances on authority while in office. Also, administrative decisions often fluctuate with partisan electoral priorities, and centralized decision-making may overlook neighborhood-level or equity concerns. Both traditional forms of government manage cities, but today’s expectations for shared governance challenge them to formalize opportunities for public decision-making.

The Resident-Model of Government

The resident model of government would propose a formalized, charter-backed structure that recognizes residents as ongoing actors in governance. The aim would be to combine the professionalism of the council-manager and mayor-council systems with the democratic legitimacy of shared decision-making. It would require creating new processes and building on existing structures to rebuild trust in democratic institutions.

The specific term for this model is up for debate, and one could use “citizen,” “civic,” “public,” or even “community.” In North America, the term “citizen” is deeply complicated. While it carries symbolic associations with democratic participation, it is also associated with national identity, legal status, racialized exclusion, and historic patterns of disenfranchisement. It has gravitas and weight that make it suitable in some ways, but it risks exclusion in others, and this balance needs to be maintained when using the term. Moreover, words like “civic” can be conflated with voting, elections, and participation in formal hearings, and “public” might not necessarily mean the people at large but rather those holding public office or the public sector.

Whatever term is used to describe this specific model of government, it must reflect the lived reality of who actually participates in local civic life in various ways, including grassroots, neighborhood, cultural participation, as well as within governmental processes. It needs to align with the municipal responsibility to serve all city residents. The term should have a value placed on belonging and agency but not assume that people’s sense of civic duty or responsibility is automatically conferred because of status.

For these reasons, “resident” is used as a place-based, inclusive term, as it does not presume that legal status and rights automatically confer political capacity, and it does not preclude being a decision-maker based on immigration status. The core of this model is that it structures political agency through institutional design, making civic practice regular and embedded in governance rather than an implied duty.

Core principles of the model include:

- Institutionalized Public Engagement: Participation moves from optional to obligatory. Mechanisms such as participatory budgeting, civic assemblies, and inclusive, equitable roundtables are codified in city charters or ordinances. For example, a city charter might require that a certain percentage of the operating and capital budget be allocated to participatory budgeting annually, with the council obligated to adopt winning projects or to formalize standing civic assemblies that regularly propose policies.

- Equity as a Governance Pillar: major policy and budget decisions include an equity impact review. Resident “equity auditors” or advisory panels assess distributional effects.

- Collaborative Policy Development: Policies emerge through co-creation. Residents participate in structured forums with staff and council members before policies are finalized. The mechanisms could or would include deliberative assemblies, neighborhood planning boards, or online policy co-design spaces.

- Transparent, Two-Way Communication: Engagement platforms, public participation dashboards, and feedback loop requirements to ensure residents see how input shapes outcomes.

The Resident Model outlined here is intended to overlap with existing council-manager or mayor-council structures, serving dual purposes: creating spaces for resident decision-making and implementation, and improving formal public connections within policy-making and service delivery among elected officials and professional administrators. Some possible institutional features of the resident model of government could include:

Charter-Level Codification

- Mandate participatory budgeting or civic assemblies as standing elements of governance.

- Create Resident Advisory Boards with formal scopes (e.g., budget oversight, equity review, planning input).

- Require annual impact reports, jointly reviewed by council and public.

Resident Governance Roles

- Resident Engagement Director (within City Manager’s office): coordinates or supports participatory processes and ensures outcomes integrate into policy cycles.

- Resident Co-Chairs for neighborhood planning initiatives.

- Community Auditors, drawn from trained resident fellows, who assess service equity and performance.

Professional–Civic Staffing

- Blend professional administration with resident collaboration by employing civic engagement professionals trained in facilitation and outreach/organizing.

- Support Resident Fellows or Neighborhood Liaisons as compensated, rotating positions within departments.

Accountability and Performance

- Publish an annual impact report tracking progress on resident priorities.

- Maintain public dashboards using resident-generated metrics alongside traditional key performance indicators for transparency and accountability.

Reimagining Civic Infrastructure

If the resident-model of government is to succeed, it must modernize the civic infrastructure cities already have, in addition to creating new institutions and processes, such as boards, commissions, neighborhood councils, and regional advisory bodies, into platforms that reflect today’s values of equity, collaboration, and innovation. These structures were initially designed to provide resident input, yet too often they function as procedural gatekeepers rather than engines of civic creativity. Official public meetings are usually limited to specific types of engagement, and these tend to leave people frustrated and wanting to feel heard.

Reforming Boards and Commissions

Across the country, boards and commissions are vital but frequently under-representative, opaque, or siloed. A resident-driven approach calls for reform on three fronts: one is composition, by replacing volunteerism-by-application with demographically representative recruitment through civic lotteries or targeted outreach to underrepresented populations. Another involves new mandates with each board having a clearly defined purpose, measurable deliverables, and a public ‘reason-response’ obligation when its recommendations are accepted or rejected, as well as better on-ramping and integration in legislative decision-making. Lastly, there should be a commitment to resident innovation teams or university partnerships to pilot solutions that emerge from deliberations, ensuring ideas move beyond advice to experimentation.

Empowering Community and Neighborhood Councils

Neighborhood-based structures should be essential for grounding citywide decisions in place-based lived experience. Yet, they often lack the resources, embeddedness, remit, and support needed to be integral to policy cycles. Under a resident model, councils gain co-planning authority over neighborhood improvement projects and can allocate a portion of participatory budgeting funds locally. Each council elects or appoints a Resident Liaison to sit within the “City Manager’s Civic Engagement Office,” bridging local concerns with citywide operations. Councils participate in annual “Neighborhood Impact Reviews” involving public forums where departments report back on service equity and progress toward resident-identified goals.

Linking Local to Regional Voices

Many policy issues, such as housing, climate resilience, and transportation, extend beyond municipal borders. A resident-driven framework can scale upward by establishing “Regional Resident Assemblies” or “Metropolitan Advisory Forums” composed of delegates from neighborhood councils and community boards. Regional planning agencies and civic assemblies could also co-host collaborative policymaking sessions to align local priorities with regional strategies. To keep these structures dynamic, cities can use open-data platforms to track project outcomes, ensuring public learning from successes and failures alike.

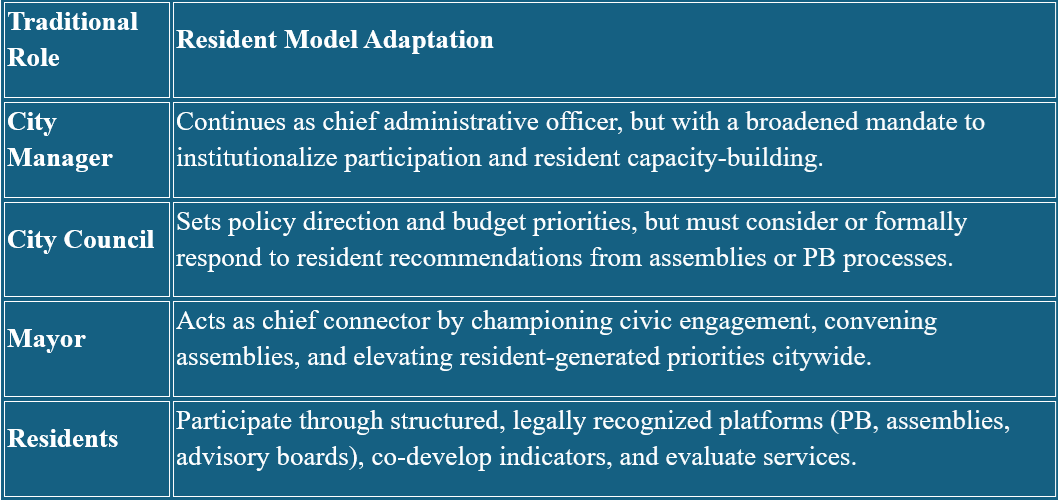

Table 1: Division of Roles Under the Resident Model

This design preserves professionalism and efficiency while expanding democratic legitimacy and responsiveness.

Connecting Invented and Invited Spaces: Micro-Grants, Neighborhood Planning Tables, and the Resident-Model as Civic Connector

A truly resident-centered model of government would recognize that civic life doesn’t begin or end at City Hall. Across neighborhoods, faith communities, mutual aid groups, and local associations, residents continually create “invented spaces” or self-organized venues for dialogue, care, and advocacy. At the same time, local governments maintain a constellation of “invited spaces” such as boards, commissions, public hearings, and consultation sessions where civic input is formally requested. The challenge for twenty-first century governance is to connect these parallel worlds so that community energy and local expertise flow directly into policymaking.

- Micro-granting programs of small funding streams for resident-led projects can bridge this divide. These programs do more than seed local projects; they serve as civic on-ramps, bringing residents into direct contact with city administration. Grantees become co-producers, and staffers gain early insight into emerging needs and ideas before they escalate into policy issues.

- At the meso-level, “Neighborhood Planning Tables” might institutionalize collaboration between residents and city staff. Each table comprises residents, community organizations, and relevant department representatives, each focused on integrated planning issues such as housing, mobility, or parks. Unlike traditional advisory committees, these tables would operate on shared work plans and joint deliverables, with city staff providing technical analysis and residents contributing place-based knowledge.

- Because the resident model of government situates engagement within the city’s operational framework, it would also become a continuous community outreach mechanism. Rather than waiting for feedback, managers and elected officials could use resident structures such as assemblies, liaison networks, and planning tables to surface emerging concerns, test policy options, and build consensus early. This two-way relationship transforms participation by having residents help define problems and solutions.

Linking invented and invited spaces requires a porous interface between places and processes that allows community-generated ideas to enter government workflows without losing authenticity. By investing in connective tissues such as micro-grants, planning tables, and hybrid fora, cities make participation both tangible and iterative, cultivating a relationship between grassroots imagination and institutional responsiveness.

Conclusion

The council-manager form transformed local government a century ago by professionalizing administration and curbing corruption. Today, an arguable political and public rupture of the existing social context beckons toward the next chapter in local government models and one in tune with resident-centered governance. The resident model of government retains the efficiency and integrity of its predecessors but redefines democratic practice for the 21st century. Just as the early reformers once reimagined cities around managerial expertise, today’s reformers can reimagine them around public knowledge and lived experiences as a form of civic expertise.

In an era when democracy must be both competent and co-owned, the resident-model of government offers a practical, principled path forward by establishing parallel and integrated means for an embedded, participatory, and deliberative democracy alongside representative governance. The resident model is timely and possibly transformative if it inserts engagement and equity structurally into governance. This also builds legitimacy and restores confidence in institutions by two-way, rather than top-down professionalism, along with a continuous need to ensure responsiveness and shared learning around changing community needs. Therefore, institutionalizing residents as co-governors is an evolution of professional administration as well.

The resident model of government aligns disparate approaches and ideas into a cohesive governance model, beyond being merely single, disconnected, or even embedded instances of democratic innovation. In other words, the objective is to move beyond single cases of political renewal and renovation. Instead, the goal is to formalize and embed “innovation” as a series of processes and mechanisms that are part and parcel of the regular machinery of governance, placing residents in an active problem-solving capacity at various steps, i.e., before, during, and after the policy-making cycle.

One of the central challenges to democratic innovation is the fear of attempting change at the scale being proposed. This is why this article began by tracing the lineage of the League’s reform-era focus on local governance and the adoption of the council–manager form of government. What began as a single city experimenting with a new model of local governance quickly spread and is now commonplace across the country.

Alongside this shift, municipalities used local charters to formalize core democratic structures and processes: periodic and free elections, terms of office, voting systems, and the respective roles of elected officials, appointed leaders, and public servants. Today, however, there is some resistance to explicitly naming new democratic innovations and resident decision-making institutions within these same charters.

This resistance reflects a deeper assumption: that established democratic practices are the only legitimate processes requiring formal recognition. As a result, alternative pathways for democratic participation, particularly those that give residents a more active and sustained role in decision-making, remain underdeveloped or absent. Yet without mechanisms that allow residents to see their voices have real, recurring influence on issues they consider essential, it is unlikely that today’s democratic climate will shift toward a more accountable and responsive system of governance.

Nick Vlahos is Managing Director of the Center for Democracy Innovation at the National Civic League.