By Rebecca Trout

In recent years, environmental concerns have slipped down the list of national problems, both in media coverage and in the public’s mind. In fact, a recent Gallup poll found that only 2 percent of respondents identified the environment, pollution, or climate change as the nation’s top problem (Gallup, 2024). Instead, attention has shifted toward the economy, immigration, international conflict, and the health of democracy. Yet the impacts of climate change have not gone away, and by all accounts, are worsening. Natural disasters are becoming more frequent and severe, the planet continues to warm—2024 being the hottest year on record (NOAA, 2025)—and rising sea levels continue to threaten human and natural habitats.

Against this backdrop, the National Civic League sought to bring these urgent challenges back into focus by inviting communities across the geographic and political spectrum to share how they are strengthening local environmental sustainability, alongside residents and local partners. The 2025 All-America City Award process showed us that despite waning public attention and shrinking funding, communities nationwide are making tangible progress through creative, inclusive, and sustained action.

“The All-America City Awards brought together an incredible group of local leaders who are finding creative ways to expand opportunity and build stronger communities. These changemakers are showing us what democracy looks like when it works from the ground up. It’s inspiring, and I look forward to following their progress and cheering them on.” – Derek Kilmer, Senior Vice President of US Program and Policy for The Rockefeller Foundation, during his keynote remarks at the 2025 All-America City Award Event.

Renewing Waterways

Historically, America’s vital waterways have served as dumping grounds for garbage, industrial runoff, and untreated sewage, turning rivers, streams, and oceans into health hazards. This was certainly the case in Akron, Ohio, where the infamous Cuyahoga River caught fire dozens of times due to years of pollution and oil spills. But the community didn’t throw up their hands, they got to work, together.

To take back their river, Akron invested more than $1 billion in 26 major infrastructure projects, including constructing storage basins, separating portions of the combined sewer system, installing storage tunnels, and upgrading the wastewater treatment plant to increase capacity.

The city also integrated green infrastructure projects to complement more traditional storm and wastewater management systems and provide added benefits for the community and environment. These include rain gardens, rainwater harvesting systems, permeable pavements, complete green streets, and more.

Given the technical nature of the work and the significant financial burden on residents, robust community engagement was essential. Residents were involved through the educational and entertaining Blue Heron Homecoming Festival, public meetings, and rain barrel and tree giveaways.

The results have been transformative. The Cuyahoga River now meets or exceeds water quality standards, supports a thriving ecosystem with the return of key species, and is poised to offer expanded recreational access along its banks.

“We didn’t just build tunnels and green spaces, we renewed trust” – Akron delegation member during the city’s presentation in Denver.

650 miles southwest of Akron, Jacksonville, North Carolina, faced similar challenges. During Jacksonville’s AAC presentation, one of the delegates shared that:

“The degradation became abundantly clear in June of 1995, when 22 million gallons of untreated hog waste spilled into the tobacco fields and flowed into the New River. Scientists warned of a large fish kill as the huge brownish red plume slowly moved down the river, but it didn’t happen, because the river was organically dead.”

Living in the only county where the New River both begins and ends, residents recognized their unique responsibility for its fate. The Jacksonville City Council issued a “moral call to action,” convening community summits to chart a path toward recovery. From these conversations emerged the Wilson Bay Initiative—an innovative plan to use oysters, nature’s own water filters, to revive the river.

Volunteers of all ages helped “chub”—or plant—oysters and placed them in Wilson Bay, while the city shut down its aging wastewater treatment plant and adjacent landfill. In their place, the community created green space and the Sturgeon City Environmental Education Center. Meanwhile, the city invested $50 million in a new land-application wastewater treatment facility on 6,300 acres, where treated water irrigates pine forests, replenishes groundwater, supports wildlife habitat, and generates $300,000 annually through sustainable timber harvests.

The results were dramatic: fecal coliform levels dropped by more than 600 percent, wetlands were restored, and marine life returned. In 2017, Jacksonville built on this success with the “Oyster Highway,” placing more than 10 million oysters across 12 living reefs to further filter the water, restore habitat, and boost recreational fishing.

Once considered beyond saving, the New River now stands as a national model of environmental recovery and civic leadership.

While in Jacksonville, a single spill exposed a decades-old environmental crisis, in Carrboro, North Carolina, a slow, persistent erosion from stormwater runoff crept across property lines and damaged the community’s beloved Bolin Creek.

Because the persistent erosion created safety hazards across both private properties and land parcels owned by the HOA, residents recognized the need for coordinated action but lacked the technical expertise and resources to address the problem alone.

The Bolin Creek Stormwater Collaborative was created to coordinate the response, bringing together HOAs, private homeowners, environmental groups, the Town of Carrboro’s Stormwater Division, and state agencies to design a sustainable, community-led solution. After the town secured a federal grant, the collaborative got to work.

“The solution was two-pronged: an attractive natural stone channel to filter the stormwater, plus a large-scale community effort where over 150 volunteers worked together to plant more than 2,000 native grasses, flowers, and shrubs to save the soil and protect the creek.”—Bolin Creek Stormwater Collaborative member during Carrboro’s AAC presentation

In addition to planting days, educational workshops and community events built awareness and strengthened neighborhood connections. HOAs also developed joint maintenance agreements, reserve funds, and signage to ensure the system’s long-term care.

What began as a localized erosion problem has become an award-winning model for watershed restoration, demonstrating that stormwater management is a shared responsibility and that lasting solutions emerge when neighbors work together.

From restoring rivers and creeks to protecting neighborhoods from stormwater damage, these communities show how environmental recovery can be rooted in civic action. Others are taking a similar community-led approach to redesign public spaces for resilience, tackling heat, flooding, and pollution.

Community-Led Green Design

“Chelsea carries heavy burdens: noise, dust, and the industry that powers Boston. But what defines us isn’t what we face, it’s how we face it, together!” —Judith Garcia, a local state representative during Chelsea, Massachusetts’s All-America City Award presentation.

With only three percent of land dedicated to parks, 80 percent impervious surfaces, and just two percent tree canopy, the city suffers from extreme heat, flooding, and poor air quality—conditions that disproportionately affect its largely immigrant, working-class population.

In response, residents launched the Cool Block Initiative, transforming one of the city’s hottest streets into a greener, healthier, and more resilient place. In collaboration with Boston University’s School of Public Health and the Boston Society of Landscape Architects, neighbors mapped heat hotspots, gathered data, and co-designed solutions.

Over 60 street trees were planted through the resident-run Tree Keeper Program, boosting the survivability rates of trees from 30 percent to 87 percent. A reflective white roof was installed on the Boys and Girls Club to deflect sunlight and reduce surrounding temperatures, while residents designed and successfully advocated for a new green space, which received unanimous city council approval.

The next phase includes planting 150 more trees and expanding the Tree Keeper Program citywide. The Cool Block is effectively cooling streets, improving health, and proving that those most affected by environmental injustice can lead the way toward lasting change.

Like Chelsea, Hampton, Virginia proves that climate resilience works best when residents lead the design process. In the historic neighborhood of Phoebus, chronic flooding and a damaged waterfront park became the focus of a yearlong, equity-driven visioning effort led by the Phoebus Partnership—a joint business and civic association—working alongside the American Flood Coalition. They sought to reimagine the park not just as a green space, but as a shared neighborhood asset shaped by the people who use it.

Even during the pandemic, the Phoebus Partnership found creative ways to engage neighbors through pop-up events, surveys, Facebook updates, yard signs, and even front-yard potluck cookouts that sparked authentic conversations about what the park meant to residents and how it could be improved. Their feedback guided a plan to restore the park’s living shoreline, expand green space, and make the area more welcoming.

Volunteers, neighbors, and partner groups came together for two full-day work sessions to remove invasive plants and install native vegetation. The city supported the effort by adapting its Adopt-A-Spot program to allow long-term stewardship.

“The city owns the land, but it’s our park, and we maintain it!” —Hampton representative during their All-America City presentation.

The project not only improved shoreline resilience and public access but also strengthened partnerships and sparked new momentum, positioning Phoebus to secure additional funding, host more events, and continue shaping its future.

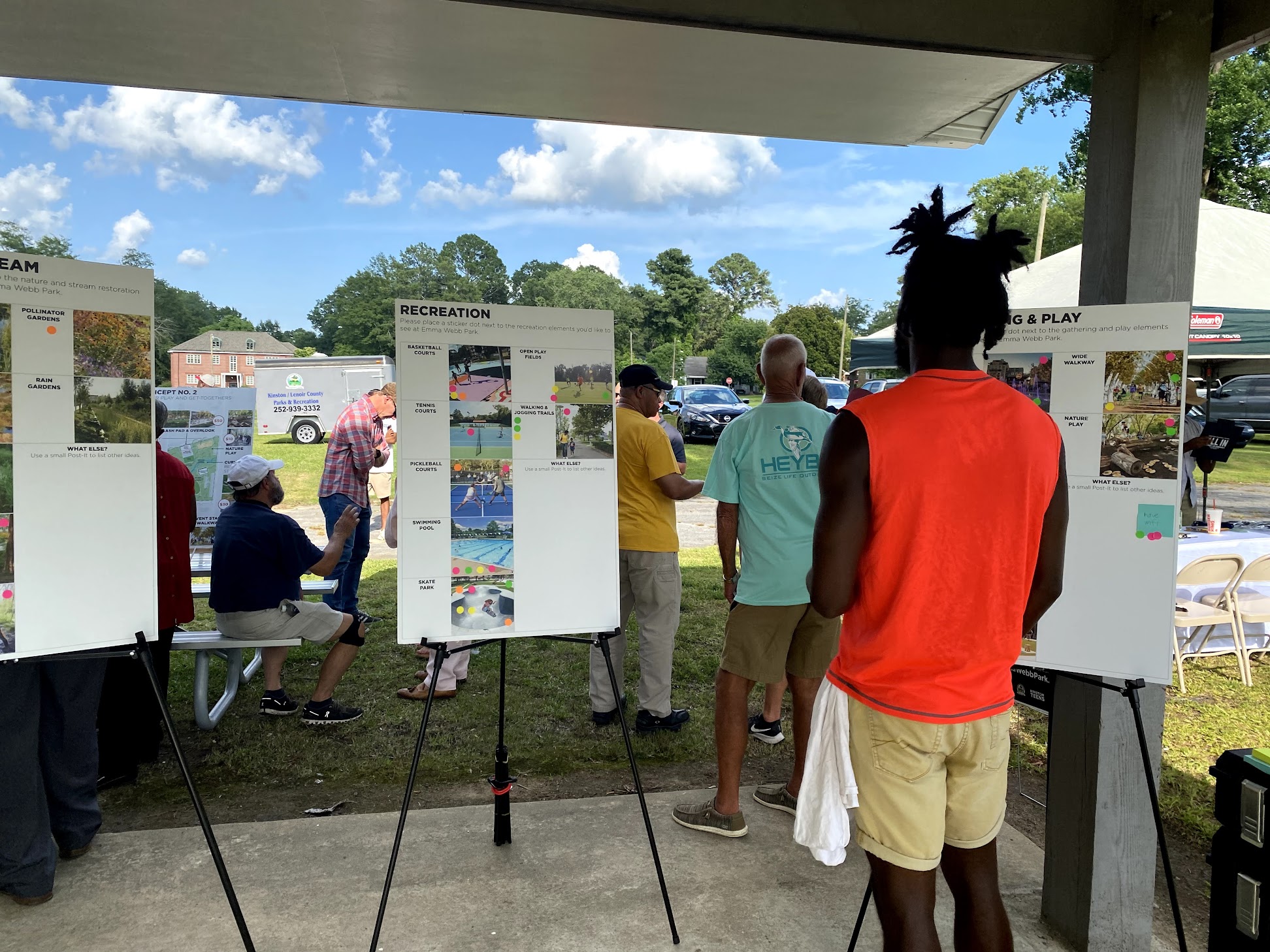

Building on the theme of community-led green design, Kinston, North Carolina, transformed Emma Webb Park, a seven-acre historic park long plagued by flooding, degraded stream systems, and outdated amenities. The city partnered with the American Flood Coalition, Design Workshop, and Kinston Teens to launch an inclusive engagement process, ensuring residents shaped the park’s future.

As one member of the Kinston delegation shared during their All-America City presentation:

“For us, engagement doesn’t end at feedback, it begins there. Every project reflects community voice and input, especially those that were historically left out.”

More than 350 community members contributed through surveys, listening sessions, pop-up events, and door-to-door outreach led by youth, prioritizing flood mitigation, accessibility, and recreational needs. Their input guided the Emma Webb Park Master Plan, which includes stream restoration, walking trails, a splash pad, basketball courts, and an ADA-accessible playground.

With $1 million in local and state funding, phase one construction is underway, and future phases will integrate public art, climate education, and cultural programming. The project demonstrates how combining resilience, equity, and hands-on community participation can turn an underutilized, flood-prone space into a safe, inclusive, and vibrant neighborhood asset.

There’s something to this whole resident-led trend, because Port St. Lucie Florida’s residents are also leading the way in shaping the city’s green future.

Port St. Lucie’s unusual beginnings as a planned retirement community divided its land into 80,000 quarter-acre lots, aiding the city’s early development, but resulting in limited and fragmented open space. As Vice Mayor Jolien Caraballo explained during Port St. Lucie’s AAC presentation:

“The original developer replaced forests with rows of homes, but what makes a city isn’t where it starts. It is the people who walk it, shape it, and grow it.”

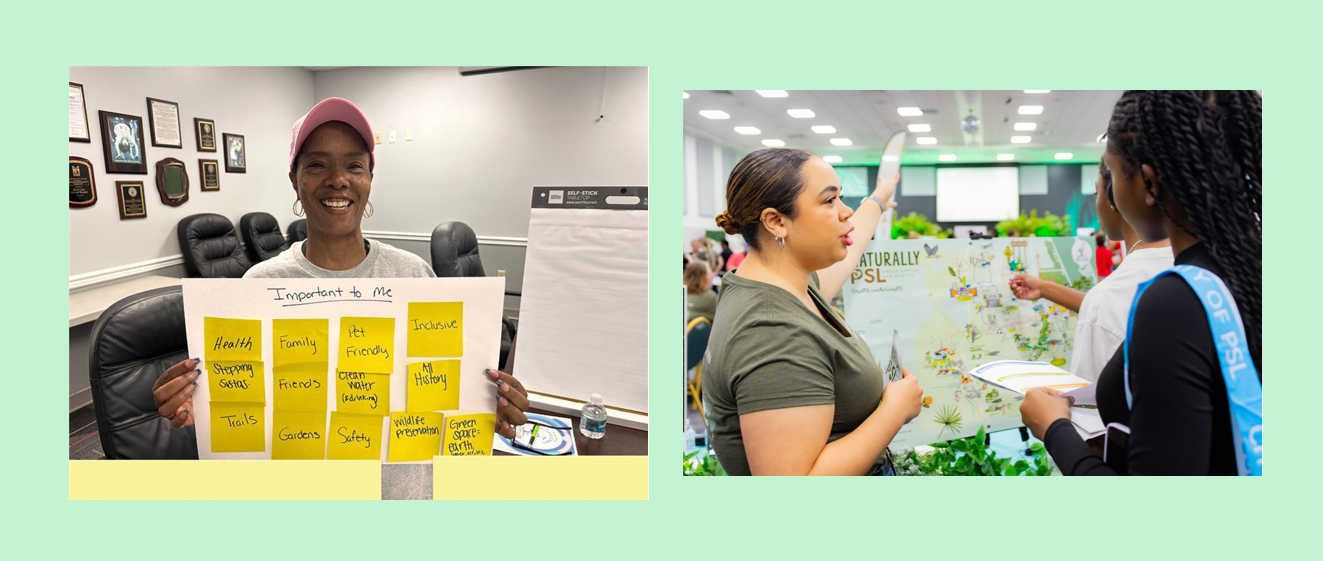

Today, with more than 250,000 residents—and nearly 50,000 added since 2020—land scarcity and concerns about disappearing green space have intensified. At the 2023 Citizen Summit, residents made their priorities clear: “Preserve more. Not everything needs to be built upon.”

In response, the city launched Naturally PSL: Green Spaces and Places, guided by High-Performance Public Spaces (HPPS), which integrate stormwater management, recreation, conservation, and even economic development into multi-functional green spaces.

A partnership with the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative helped the city engage more than 900 residents through interviews, walking tours, and design sessions, generating over 1,000 ideas.

Among the most popular ideas were:

- Buzz Stops – pollinator-friendly gardens atop bus shelters.

- Explore PSL – maps and signage to connect residents with over 40 miles of trails and parks.

- Green Land Bank – a dedicated fund for conservation land acquisition and maintenance.

Launched at the 2025 Citizen Summit, Naturally PSL now includes a citywide trail map, a Conservation Corps, and a Stewardship Award program, proof that resident-led action can redefine growth and preserve the natural character of a fast-growing city.

The Power of Planning

Comprehensive planning, especially in larger municipalities, helps communities navigate the complex tradeoffs between economic utility, quality of life, and environmental and aesthetic priorities. The best plans are created with residents and community partners—businesses, schools, civic associations, and faith-based institutions—so that shared priorities can be translated into clear, measurable, and achievable goals. While comprehensive plans have become commonplace (and often legally required), sustainability and environment-specific plans are still relatively new. Yet, as several of our 2025 All-America City Award communities demonstrated, they are essential for building cities that are both livable and environmentally sustainable.

From the 1970s through the early 2000s, Memphis responded to population stagnation by annexing more than 100 square miles of suburban land, doubling the city’s footprint without increasing density. With no comprehensive plan in place for nearly 40 years, the city’s strategy left behind fragmented development and deep disinvestment in core neighborhoods.

By the mid-2010s, residents were demanding a voice, so city leaders launched Memphis 3.0, the city’s first comprehensive plan in decades. Determined to build a plan rooted in community voice, the city partnered with nearly 50 organizations, hosted neighborhood walking tours, and held more than 400 public meetings. More than 15,000 residents shaped the plan’s vision, prioritizing walkability, neighborhood identity, and equitable economic growth.

“For me, it means the city finally listened to kids and families. It means my neighborhood matters.” —Resident reflection during Memphis’ jury presentation.

The plan centers growth around “anchors”: walkable, transit-connected hubs tailored to each neighborhood’s character and needs. Aligned with broader sustainability goals, Memphis 3.0 advances denser, mixed-use development that reduces emissions while enhancing quality of life.

Since its unanimous adoption in 2019, the plan has engaged more than 73,000 residents and spurred about $900 million in local investment. Now in its fifth year, Memphis 3.0 is undergoing its first update, continuing to chart a resilient, resident-driven future.

Seattle, Washington, is no stranger to planning. From the robust One Seattle comprehensive plan to targeted efforts on housing, tribal engagement, food access, and more, the city regularly works with residents and partners to plan for a future that everyone can get behind.

With transportation being the largest source of climate pollution in Seattle, responsible for nearly two-thirds of the region’s greenhouse gas emissions, it’s no surprise that Seattle City Light (SCL) launched its first Transportation Electrification Strategic Investment Plan (TEISP) in 2020. Over the next four years, the utility installed more than 905 EV chargers, supported fleet transitions, and helped electrify public transit. By 2024, one in four new vehicle sales in King County was electric.

Despite this progress, affordability and access remained major barriers, especially for low-income and BIPOC communities disproportionately harmed by transportation-related pollution. In 2024, SCL began updating the TEISP by partnering with Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods, Community Liaisons, and nonprofits to ensure the plan reflected community priorities. Outreach efforts reached 500+ residents across 10 neighborhoods and 24 cultural communities through events, interviews, surveys, and hands-on activities.

Adopted in January 2025, the updated 2025–2030 TEISP prioritizes grid readiness, public and workplace charging, green workforce pathways, and sustained partnerships with community-based organizations to ensure inclusive and resilient transportation electrification.

“We’re not done yet, we know innovation and resilience already exist within our communities and it’s our job to resource that resilience.” —Angela Song from SCL during Seattle’s presentation.

In Tallahassee, Florida, “When everybody has a seat at the table, we soar to new heights.”

And they’re going to need to soar if they’re going to meet the ambitious goal of their Clean Energy Plan (CEP), adopted in 2019, which aims for 100 percent net clean renewable energy by 2050.

Community engagement was central to the plan’s creation. The city hosted forums, conducted surveys, and formed stakeholder advisory groups involving local universities, businesses, and advocacy organizations. More than 2,400 residents participated in surveys, and more than 300 attended public sessions. Outreach to underserved communities included translated materials and tailored workshops to ensure equitable participation.

This extensive community input made sure the plan emphasized sustainability, affordability, and grid resilience, especially for underserved communities. Key actions include expanding solar energy, implementing energy efficiency programs, and enhancing grid resilience with smart technologies and battery storage. Since its launch, solar capacity has tripled, and energy burdens for thousands of households have decreased. The city has also improved energy reliability, particularly during severe weather events.

During Tallahassee’s widely viewed All-America City Award presentation, we learned that:

“Tallahassee was the first city in Florida to power all city municipal building with our own solar energy.”

Tallahassee’s energy transition is supported by strong partnerships, including collaborations with Florida A&M University and Florida State University. The city’s efforts have earned a LEED Gold certification and strengthened public-private partnerships. With continued focus on renewable energy expansion and equitable access, Tallahassee is on track to achieve its 2050 goal, fostering a sustainable, inclusive future for all residents.

Despite the myriads of issues competing for our time, attention, and resources, we cannot ignore one of the most pressing and all-encompassing threats to our waters, lands, and health. The interventions showcased here—waterway restoration, green design, and bold sustainability planning—are not just projects, they are reminders of what’s possible when communities come together with creativity and purpose. But possibility alone is not enough. We must continue to resource, support, and amplify the work of this year’s All-America City Award recipients and of all communities daring to build a more sustainable and thriving future.

Rebecca Trout is the Senior Director of Programs and Partnerships at the National Civic League and Director of the All-America City Award Program.