Riding the Waves of Democracy Innovation: The Pressures, People, and Ideas Shaping the Future of Citizenship

The terms “democracy” and “citizenship” aren’t usually associated with innovation. People tend to think of them as historic ideas that don’t change over time. In fact, democracy and citizenship are dynamic: many innovations have emerged in the last thirty years, all over the world, at all levels of governance.

These adaptations and reforms are spurred by various crises and pressures, they are aimed at many different public problems, and they are intended to uphold many different public values, from racial justice to social cohesion to economic vitality to public health. Most of these innovations embody a broader definition of “democracy” – it is not just about voting, but about other ways of encouraging citizens to help make public decisions and solve problems. Most of them also take a broader view of “citizenship” – it includes everyone, not just people who are citizens in a narrow legal sense.

For the most part, these innovations have not been connected. Though there are some common influences, and some of the same basic practices have been shown to work in different contexts, these are very decentralized developments. Scientific innovations often occur because researchers compare notes, see each other at conferences, and critique each other’s papers and patents. Unfortunately, many of today’s democracy innovators think they are alone.

This essay is too short to give you more than a brief glimpse at the pressures, people, and ideas shaping the future of citizenship and democracy. For more, consult resources such as Participedia, DemocracySpot, the Civic Tech Field Guide, Thirty Years of Democratic Innovations in Latin America, Catching the Deliberative Wave, Democratic Innovations, Imagining Better Futures for American Democracy, or the book that Tina Nabatchi and I wrote, Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy. Soon you’ll be able to get a bird’s-eye view of the American part of this landscape with the release of the Center for Democracy Innovation’s Healthy Democracy map at the National Conference on Citizenship. We’ll present a bird’s-eye view of the American part of this landscape – both the new innovations and the more time-honored varieties of democracy-strengthening work. The map contains thousands of organizations categorized by the different kinds of democratic work they do, all of which aim to enhance the quality of civic life in America.

The table below lists at least some of the main waves of innovations, when they emerged, what inspired them, and who was involved. The innovations are listed in alphabetical order, as are the key figures. The table includes innovations that emerged in other countries and then were adopted or adapted in the U.S. Many of these innovations are based on or revivals of older practices; the table focuses on developments from the 1990s onward.

Three caveats:

- The category of election reforms is difficult to summarize because there are so many people and ideas at work in that space, and because many of the reform ideas being debated belong to an earlier period of innovation, in the late 19th-early 20th Century. I’ve only listed innovations that emerged more recently.

- Most of these innovations owe much to the ideas that came before them – some of them are simply older innovations that have been renovated for current conditions (for example, by adding digital tools and practices).

- Not everything good is innovative, and not everything innovative is good. There are many time-honored practices, like voting and volunteering, that are good for democracy. And readers can and should critique these innovations and identify their strengths and shortcomings.

The table is not intended to be exhaustive or definitive. It will no doubt spur debates! Consider it a starting point for trying to survey the innovation landscape.

| Wave | When and where did it start? | Why | Some key figures | Some representative innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civic journalism, public journalism, citizen journalism | Early 1990s in Wichita, Kansas, Seattle, Washington, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and other places | Rebuild trust and interaction between journalists and citizens | Darryl Holliday, W. Davis “Buzz” Merritt, Maria Ressa, Jay Rosen, Robert Rosenthal, Maria Ressa, Jan Schaffer | Interactive candidate forums, nonprofit media and investigative reporting organizations, community “documenters” |

| Deliberative forums | Early 1980s | Gather informed input on public decisions, galvanize people to help solve public problems | Betty Knighton, Carolyn Lukensmeyer, David Mathews, Daniel Yankelovich | 21st Century Town Meeting, National Issues Forums, study circles |

| Dialogue and problem-solving to strengthen race relations and racial justice | Mid-1990s, first in Los Angeles, California and Lima, Ohio, then in many other places | Address root causes of civil disturbances, address structural inequities in Los Angeles, other cities | David Campt, Rob Corcoran, Lani Guinier, Glenn Harris, Martha McCoy, Pedro Noguera, john powell, Lori Villarosa, Iris Marion Young | Dialogue-to-Change programs, study circles, action forums |

| Digital direct democracy | Early 2000s | Use Internet to reveal and galvanize large-scale public support for policy positions | Marci Harris, Eli Pariser | e-petitions, live polling, open law portals |

| Digital deliberation | Early 2010s | Use Internet to gather informed input on public decisions | Amy Lee, Michael Neblo, John Richardson, Audrey Tang | Pol.is, Ethelo, Deliberative Townhalls |

| Digital ideation and crowdfunding | Late 2000s | Use Internet to collect, rank, and refine ideas, and raise money and volunteer commitments, from large numbers of people | Erin Barnes, Clay Shirky | AllOurIdeas, ioby, Kickstarter |

| Digital data-gathering and feedback on public problems and services | Early 2010s | Use Internet to engage large numbers of people to detect public problems (as small as potholes and graffiti) or give reactions to public services or initiatives | Heidi Grunwald, Nigel Jacob, Chris Osgood, Tom Steinberg | FixMyStreet, SeeClickFix, online survey panels |

| Digital tools for grassroots relational organizing | Mid-2000s | Use Internet to complement older face-to-face methods for grassroots organizing and collective action | Marshall Ganz, Hahrie Han, Rinku Sen, Makani Themba | Outreach Circle, student voice organizations, protest mapping |

| Digital tools for voter information and education | Early 2010s | Use Internet to help people understand how to vote and give them information they want on candidates | Seth Flaxman, Sara Gifford | TurboVote, Ballotpedia, ActiVote |

| Election reform ideas (see also digital tools for voters, below) | Many of the electoral changes being debated today first emerged in a much earlier period of innovation, in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries | Deal with increased gerrymandering, fewer competitive elections, increased influence of money in politics, decreasing trust in elections, and other challenges related to elections | (Innumerable innovators, architects, and advocates) | Electronic voting, independent redistricting commissions, ranked-choice voting |

| Food-centered community-building initiatives | Early 2010s in Chicago, Illinois, Detroit, Michigan, towns in West Virginia | Strengthen social networks and build relationships among large, diverse numbers of people | Cheryl Hughes, Sean Mann | Detroit Soup, “Meet and Eat” (West Virginia), “On the Table" (Chicago and other cities) |

| Hyperlocal online networks | Early 2000s in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota, Vermont, and many other places | Use Internet to facilitate information-sharing, problem-solving, and community-building among people who live in the same neighborhood or town | Steve Clift, Nirav Tolia, Michael Wood-Lewis | e-democracy.org, NextDoor |

| Impact volunteering | Early 1990s in Seattle and other cities | Inspire volunteerism and help Americans (young people in particular) learn from their service experiences | Jim Diers, Myung Lee, Peter Levine, Scott Warren | Love Your Block, action civics, microgrant programs |

| Mini-publics (deliberative processes with citizens selected randomly) | Late 1990s for consensus conference (Denmark) and deliberative polling (Texas), mid-2000s for citizens assembly (British Columbia) and Citizens’ Initiative Review (Oregon) | Overcome legislative gridlock by gathering informed input from a microcosm of the population, to submit recommendations either to officials (on a policy decision) or to voters (on a ballot initiative) | Ned Crosby, Jim Fishkin, Janette Hartz-Karp, Lars Klüver, Art O’Leary, Jane Suiter | Citizens’ assembly, citizen jury, Citizens’ Initiative Review, consensus conference, deliberative polling |

| Participatory budgeting | 1989 in several Brazilian cities; early 2000s in Chicago, then New York City and others | Give citizens a meaningful say in how public funds are spent, and in the process to reduce poverty and strengthen community connections | Shari Davis, Olivio Dutra, Brad Lander, Josh Lerner, Joe Moore, Tarson Núñez | Participatory budgeting (PB), digital PB, school-based PB, district-based vs. city-wide vs. national PB |

| Participatory planning | Early 1990s but based on many earlier ideas | Give people meaningful roles in designing, planning, and managing the built environment and how land is used, so that public spaces work better for the people who use them | Peter Dienel, Jane Jacobs, Fred Kent, Elinor Ostrom | Planning charrettes, placemaking, community land trusts |

| Truth and reconciliation processes | Mid-1980s (Argentina), mid-1990s (South Africa), early 2000s (Greensboro, NC) | Investigate, reveal, and address injustices and broken trust related to past wrongdoings | Raúl Alfonsín, Murray Sinclair, Desmond Tutu | Truth and Reconciliation Commissions |

There are many other sets of innovations, such as serious games, participatory grantmaking, and texting-based engagement, that are noteworthy and interesting but may not qualify as a “wave” of innovation.

The table above presents a whole menu of options for people to decide how they want to make citizenship and democracy more participatory, equitable, and meaningful. Most of these ideas are compatible with one another rather than in conflict, but they do represent different choices and priorities for us to consider. What all these innovations have in common is that they amplify, inform, and support the voices of citizens in governance.

Waves of innovation in democracy have carried citizens, communities, and institutions to our current position: a point where we can make some significant decisions about how we want to govern our communities and country. We should face them now, before the next wave of technological changes – powered by the increasing sophistication and influence of Artificial Intelligence – makes our political reality even more complicated and hard to control. Events like the National Conference on Citizenship and the All-America City Awards can help us celebrate, connect, and learn about both the waves of innovation and the choices we now face.

*The author would like to acknowledge several anonymous contributors for their helpful comments on a draft of this piece.

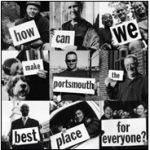

- Portsmouth (NH) Listens, 1998

- Pol.is and vTaiwan 2016

- The Government Asks, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2014