By Maura J. Casey

In April of 2015, Deanna Watson was helping her community cope with a devastating drought that threatened the future of Wichita Falls, Texas, near the border of Oklahoma. The drought had lasted four increasingly frightening years in the north Texas region. The lack of rain had completely dried up 2,200-acre Lake Wichita, killing all marine life. The reservoir was down to nearly 20 percent of reserves.

As the editor of the Wichita Falls Times Record News, Watson’s newsroom leadership and the stories her reporters produced made a difference in helping the area survive. The newspaper did this not merely through marshaling facts or by quoting learned experts and people in power, although, some of that was necessary. Rather, the staff put ordinary people at the center of many of the 250 stories written throughout the course of the drought.

As the editor of the Wichita Falls Times Record News, Watson’s newsroom leadership and the stories her reporters produced made a difference in helping the area survive. The newspaper did this not merely through marshaling facts or by quoting learned experts and people in power, although, some of that was necessary. Rather, the staff put ordinary people at the center of many of the 250 stories written throughout the course of the drought.

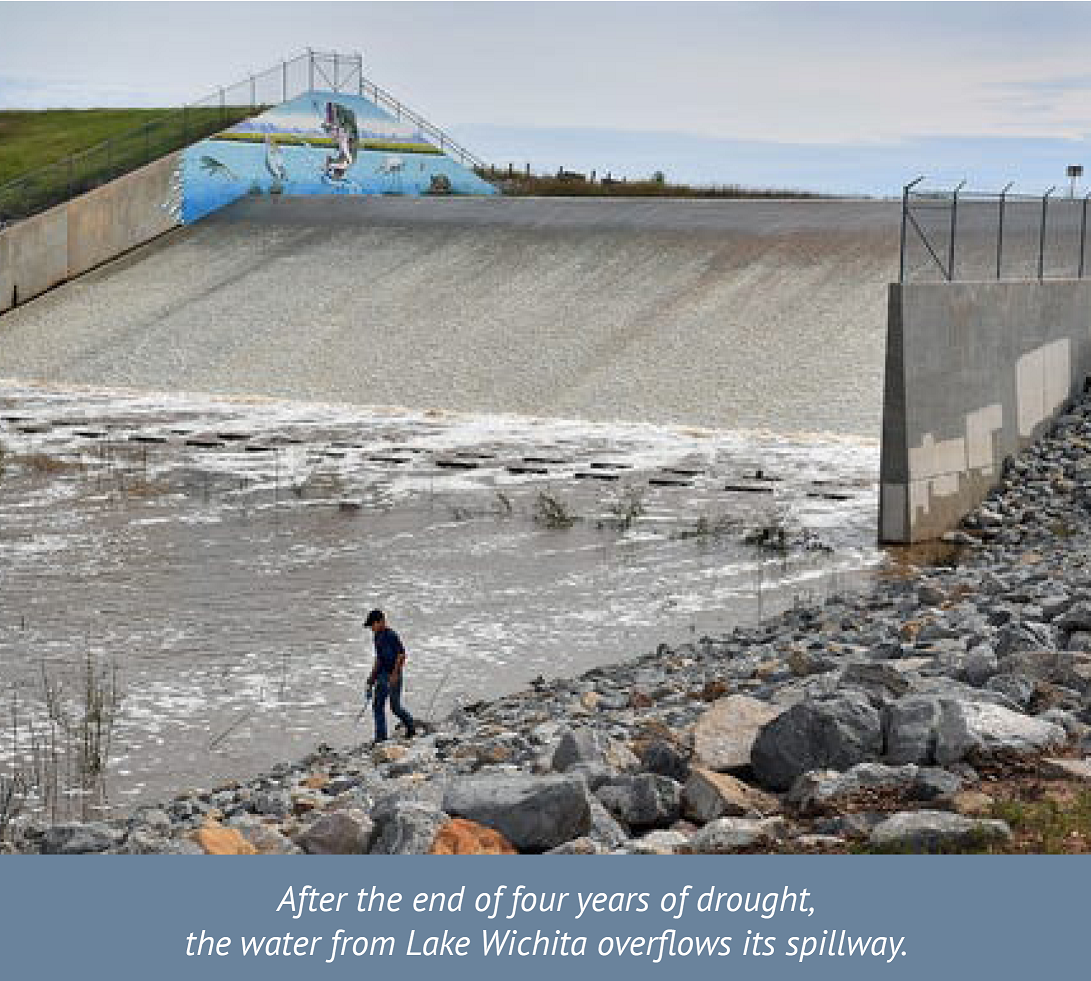

Newspaper stories and Watson’s opinion columns helped readers see that the drought was a shared public problem, and that they were all, collectively, the heroes they were waiting for. The stories centered on the many actions that ordinary individuals could perform, not just government. Saving water became a point of pride. Driving a dirty car became a status symbol. Every day Watson ran on the front page the most interesting suggestions for conserving water. And when the heavens finally opened a month later in May, when it rained day after day, people gathered spontaneously to celebrate on the shores of Lake Wichita when the water overflowed the spillway.

They knew their immediate worries were over, but they haven’t stopped saving water, Watson said. “We as a community continue to conserve at remarkable levels. We’re like Depression era kids who don’t waste water even though we have enough,” Watson wrote in an email.

Her story illustrates something I have learned, not in my opinion-writing career spanning three decades and four newspapers, but at the Kettering Foundation of Dayton, Ohio where I am a senior associate and where I heard Watson discuss the drought coverage at a meeting of journalists. Democracy is far more than a system of governance, checks and balances. It is organic, woven into traditions, everyday habits and routines, some professional and some personal.

The Times Record News reporters helped people see their role in our democracy by putting them at the heart of how they covered the story. This kind of reporting fits into the approach of the Kettering Foundation, which researches how democracy can work as it should. The foundation isn’t in the news business., but it does look at practices across many professions that help people in their work of citizenship, laboring with others on issues, or what the foundation refers to as shared public problems. Those problems can be very different from one another, involving something as relatively minor as the need to fill potholes to the national problems of affordable health care, the scope of gun violence, or a regional drought.

Six democratic practices

Simply put, when people gather and say to one another, “What should we do?” about a public problem, the Kettering Foundation gets intrigued and tries to learn from whatever happens next. The Foundation works with journalists and others who want to encourage people’s ability to recognize a shared public problem and see a role for themselves in addressing it. The Foundation regularly brings together radio, broadcast and print reporters who are experimenting with ways to help people see themselves as central to, not detached from, addressing shared public problems.

The foundation’s research has identified six core democratic practices that help people work on issues together naming, framing, making decisions deliberately, identifying resources (even intangible ones, like enthusiasm) organizing actions and collective learning that keeps actions going and creates change. Some journalists have applied these practices to their own work.

The first two practices, naming and framing, involve something every journalist does every day. Some stories are obviously simple. If there is a car accident on the highway, asking who was hurt, why it happened, when it happened and where it happened, will likely suffice.

But most other issues cry out for a more thoughtful approach. Naming and framing require listening carefully to how people talk about issues, putting terms into ordinary language and being willing to question the language of experts. Speaking in ordinary language also helps identify a wide range of actions as solutions.

For example, when soaring real estate prices in Nashville caused affordable housing to be harder to find, the Tennessean’s Opinion and Engagement Director David Plazas didn’t hear people use expert terms such as “gentrification” to talk about the issue. Instead, while taking a bus to his job, he heard people say things like, “I just don’t recognize my neighborhood anymore.”

Plazas’ actions were significant because he listened first. “He tapped into a conversation that was already going on,” observed David Holwerk, the Kettering Foundation’s communications director and a former newspaper editor. Plaza’s listening helped him realize the nature of the issue and he convened citizen forums to talk more. The resulting series examined every aspect of this topic and laid out a very wide array of choices for the public with suggestions that came from citizens themselves, not just experts.

People want journalists to help them connect to one another, not just feed them facts from above, say reporters and editors who question the traditional media approach. When a journalist helps people connect to issues and their community, it strengthens democracy and has the potential to create more trust in the media. In return, reporters often get stories rich in nuance, with far different angles than they would have gotten without listening to people first.

Connection, not just information

When I look back on my career, too often I was on automatic pilot when it came to naming and framing. And I suggest that many of my brother and sister journalists are too. With the benefit of hindsight, I would argue that not questioning—rigorously—the name of issues or how the issues are framed at the beginning of the reporting process not only leads to stories that are less interesting, it leads to a lack of trust, and the perception on the part of the public that journalists don’t care. It has had a troubling impact on the media at all levels.

For example, I was taught in journalism school to cover public issues by attending a hearing, interviewing the politicians or experts at the hearing, interviewing one or two people who attended the hearing, and writing the story.

But that, too often, means covering government – not the governed.

Adopting the terms and words that experts and lawmakers use, and putting them at the center of stories, embraces how they frame the issue. The practice unintentionally sidelines ordinary people from politics and public life.

Doug Oplinger, a journalist of 50 years experience and project manager of Your Voice Ohio, would go further. Your Voice Ohio has in the last five years helped 60 newsrooms engage with their communities. Currently, Oplinger is working with more than 50 news organizations in an Ohio election collaborative. Several years ago, he joined the Kettering Foundation for its Katharine W. Fanning Residency in Journalism and Democracy. The residency enabled Oplinger to work for five months at the Foundation, meeting with journalists and doing research on ways to strengthen the media and democracy.

Oplinger believes that journalists need to listen to ordinary people first before they begin to frame their stories, despite the time pressures with which reporters must contend. He also thinks that instead of being satisfied with merely covering the sides of an issue, reporters need to find solutions to problems and report on them – whether or not those answers are mentioned at a public hearing.

He said that journalists tend to cover an issue as if there are only two sides, missing the complexity that exists and, in fact, what people yearn for in news coverage. And, he said, news consumers are looking for ways to improve life. Reporters who go deep into complexity – examining competing interests and life experiences – and emerge with shared values and solutions become of greater value to the people in their communities. Shared values and solutions aren’t likely to emerge from coverage of public meetings. They require new forms of reporting and interviewing that rely on dialogue and engagement.

In Oplinger’s view, journalists should “stop telling people their lives suck. They already know that. Tell them some solutions to help them,” he said, and work with people to hear what solutions they have to offer.

Stop worrying about advocacy

Yet many journalists believe this approach would require them to take sides and would make them advocates instead of impartial observers.

“We have to get out of the debate in our heads about advocacy,” Oplinger said. “Journalists say, ‘if I cover solutions, then I become an advocate.’ But if you just cover government and what special interests say, you are already being advocates and you are leaving 11 million Ohioans out of the conversation.”

As an editorial writer for more than 30 years I was paid to have opinions, so I didn’t have to worry about being seen as an advocate. But too often, I unthinkingly adopted the language of experts, which often can create barriers to communication instead of a broader understanding of the issue.

For example, when writing about education, I often used the term, “the achievement gap.” This is shorthand for referring to the gap in educational test scores between well-off, often white students who perform better than their poorer fellow students. Yet using this expert term takes this crucial issue out of the realm of citizens and puts the subject squarely in the hands of educational officials. The “achievement gap” is not a term that ordinary people in their right minds would use. Yet I used it repeatedly.

The term is limited, bureaucratic, and doesn’t begin to convey the subject’s complexities. For maybe the issue isn’t merely underperforming on tests. Maybe it is a hunger gap. Maybe it is the lack of transportation – the inability of a student to stay late for extra help because no buses will be available for a ride home. Maybe class sizes are too large, or teachers overwhelmed.

Obviously, news stories must contain information gained from highly educated, expert sources who have a deep understanding of issues. But if journalists pay attention when they talk with ordinary people affected by those issues, they often realize that these non-experts discuss issues in terms of what is important to them, using words unlike the language of experts. Instead, the terms that ordinary people use very often reflect fundamental concerns such as freedom, security or fairness that are crucial reflections of their own life experiences, which can often shed new light on a story. Putting an issue into ordinary terms also can help journalists, readers and viewers identify a whole range of options for solutions.

Michelle Holmes, who in 2014 was vice president of content for AL.com, steered the news site into what she calls, “connected journalism,” that which helped communities connect with residents and helped citizens connect with each other and solve shared public problems. She championed projects that offered ideal conditions for a feeling of human connection, transformation and healing through storytelling. She saw a role for journalism in helping people feel less alienated and powerless.

The news site’s prison reform series in 2014 exposed conditions in Alabama’s prisons and sparked citizens to demand change. It also led to an insight. The issue was framed as prison overcrowding, but readers didn’t buy it. Readers believed that the prisons were overcrowded because people were being imprisoned who should not have been sent to prison in the first place.

Ordinary people framed the issue as one of fairness. It was not about having too few prisons, but having too many prisoners – a big difference.

Media tensions and the pandemic

There are many innovative organizations that have formed in the last decade to help the media adjust its approach, among them Solutions Journalism, Resolve Philly, Hearken, City Bureau and Spaceship Media. But the push for the media to cover stories differently comes at an increasingly perilous time for newspapers in particular. Even newsrooms that are open to change contend with the competing pressures of falling revenue, many more stories to cover with fewer journalists, and an increasingly contentious atmosphere. The conditions are not optimal. And did I mention that the country is in the middle of a pandemic?

The Covid-19 pandemic is easily understood as a shared public problem, one in which the actions of many ordinary people will help determine the health of the community.

“There are a lot of similarities to the drought,” said Watson, and when the challenge of the virus became apparent, her region swung into action just as it did in conserving water years before. Women began to sew masks and most people wore them in public without complaint. Businesses switched to curbside service. The community, hungry for information, turned to the newspaper, where the Covid-19 stories have gained a wide readership.

But there are tensions also, Watson said. During the drought, she pointed out, the U.S. didn’t have a president who routinely attacked the media, calling them the “enemies of the people.” “Fake news” was an unknown term. And during the drought, the newsroom staff was much larger than it is now. They have managed to produce just as much content this year as last, despite the difficulties. But the pressures facing journalists and the media are unrelenting.

Can the journalists help people see their own roles in public life, in democracy, in civic life, soon enough to improve their lives and help media companies survive?

Oplinger hopes so. “There are so many crises right now that if we are unable to help people through this, we have committed suicide,” he said.

With regard to the pandemic, Oplinger said he has seen too many stories on the groceries that the upper class can have delivered, and not enough from the viewpoint of people who have to catch a bus to go to a store and purchase just enough food as they can carry home.

“Journalists need to ride the bus,” he said. “We need to listen to people’s problems and how they are solving them. If we write stories about regular folks, their tribulations and successes, that is useful journalism.”

Maura J. Casey is a former editorial writer for The New York Times and a senior associate of the Kettering Foundation.