Larry Schooler

In the last few decades, the field of public deliberation has experienced significant growth in the number of practitioners focusing on public engagement as a profession or occupation. Across the country, a growing number of practitioners are receiving specialized training and making their living in the design and convening of public engagement.

At the same time, more and more governments–particularly at the local level but also in counties, regions, and states–have worked with such professionals to evolve their public engagement strategies away from the “three minutes at the microphone” public hearings that satisfy few citizens’ needs and give the impression that important decisions have already been made. The profession has helped governments involve citizens earlier and more meaningfully than in past hearings held the night of a vote. Decisions made by those governments incorporate more of the public’s interest and often prove more politically sustainable.

So, where might that leave those who care deeply about including the public in political deliberation but who have another professional calling? What about those who have retired and lack the stamina for a full-time job but would love to be involved? What about full-time students focused on academics but interested in internships, course credit, or community service?

For every one professional athlete, thousands of amateurs play pickup games in the spare time. For every Broadway actor, hundreds take up theater as a hobby on a community stage. For every band with a hit single, there are dozens of musicians jamming in garages or playing covers in bars.

The “professionalization” of these activities, or forms of art, has obviously not stopped those with far less training and skill from taking up the craft. If anything, we often see an upsurge in hobbyists when a professional rises to prominence—think of the impact Tiger Woods had on golfing, or how “American Idol” inspired shower singers to take the stage. Why shouldn’t the professionalization of public deliberation encourage more “amateurs” to participate in community planning and problem-solving efforts?

Across the country, governmental and nonprofit organizations are finding that volunteers can play a critically important role in the success of public engagement endeavors.

The number of public engagement “professionals” (defined as those who make most or all their living doing this work) does not seem to meet the demand for public engagement nationwide–especially in cities where engagement may happen on multiple topics simultaneously. Moreover, government agencies have rarely been able to find funding to create these positions internally or to train staff on best practices in public engagement, leaving a gap between their needs and the resources to meet those needs. Volunteers can help fill that gap.

Consider the difference between what a professional and a volunteer (or an amateur) might bring to their work in this field. Those who come to this work as volunteers often bring the perspective of their other profession or career and a different way of framing questions to discuss with the public or respond to comments made during dialogue. They may also bring a special level of passion and commitment to their opportunity to facilitate; they may view it as a unique opportunity for them in ways that professionals doing the work every day might not.

Additionally, while many public engagement professionals or volunteers do work in their own communities and are recognized and trusted by community members, they often “parachute into” a community where they lack relationships that local volunteers might have. Using trusted members of the community might make others feel more comfortable participating in a public dialogue, particularly if the volunteers are hosting dialogue in their homes or in familiar local hangouts, rather than governmental facilities.

All these assets (and others) have led several communities to embrace the role of volunteers in public engagement. For instance,: in Arizona, Project Civil Discourse has involved volunteers as facilitators of small group discussions held at forums on issues affecting quality of life in the state. They call upon all participants to follow a pledge: “I pledge to engage in the basic principles of civil discourse: to respect diverse points of view, listen with an open mind and speak with integrity. I call upon all civic leaders to meet the challenge of solving difficult social issues by adhering to these principles, thereby creating a better world for ourselves and future generations.”

In the Pacific Northwest, the Countywide Community Forums empowered residents in the greater Seattle area to discuss local issues facilitated by volunteer hosts. Participants could register online to find conveniently located meetings and join a group of between 4 and 12 participants discussing a common topic, introduced by a video. Participants and their volunteer host even decide on a meeting place and time. In an evaluation of the program, the King County Auditor’s Office reported, “Overall, participants are satisfied with this engaging, nonpartisan effort and report that they learn about the topic and King County policies.” The auditor recommended that the Forums “engage [volunteer] citizen councilors and others in providing feedback and ideas and helping make the program more attractive to users.”

Chicago developed a model replicated in other cities (including Columbus, Ohio) known as “On the Table,” in which thousands of volunteers host dinner dialogues to discuss the challenges and opportunities facing the local community. Some 55,000 people participated in roughly 3,500 volunteer-led dialogues in 2016, with dinners occurring in private homes or offices and public spaces (up to the host’s discretion). The Chicago Community Trust, which helped organize the day of dinners, reported that out of the respondents from 2016 who participated in On the Table in previous years, 57 percent participated in follow-up conversations over the past year; 46 percent stayed in contact with other attendees and 24 percent worked with one or more attendees on an idea.

One third of surveyed 2016 participants also said they made specific plans to work with one or more attendees. More than three-fourths of those surveyed said the dinners helped them better understand both community issues and how to address them. Everyday Democracy’s Anchor Partner InterFaith Works in New York hosts a similar dinner dialogue program, aimed at promoting deep inter-faith conversations.

In nearby Oak Park, Illinois, Dinner & Dialogue gave community volunteers a chance to host discussions in their homes over meals paid for by the City of Oak Park on various topics, including diversity, race, and inclusion.

Some communities have created nonprofit organizations to recruit and train volunteers to facilitate dialogues and conversations regularly. Others have received help from universities or libraries that have active public deliberation programs. In Fort Collins, Colorado, Colorado State University’s Center for Public Deliberation trains students who volunteer in the community in this way.

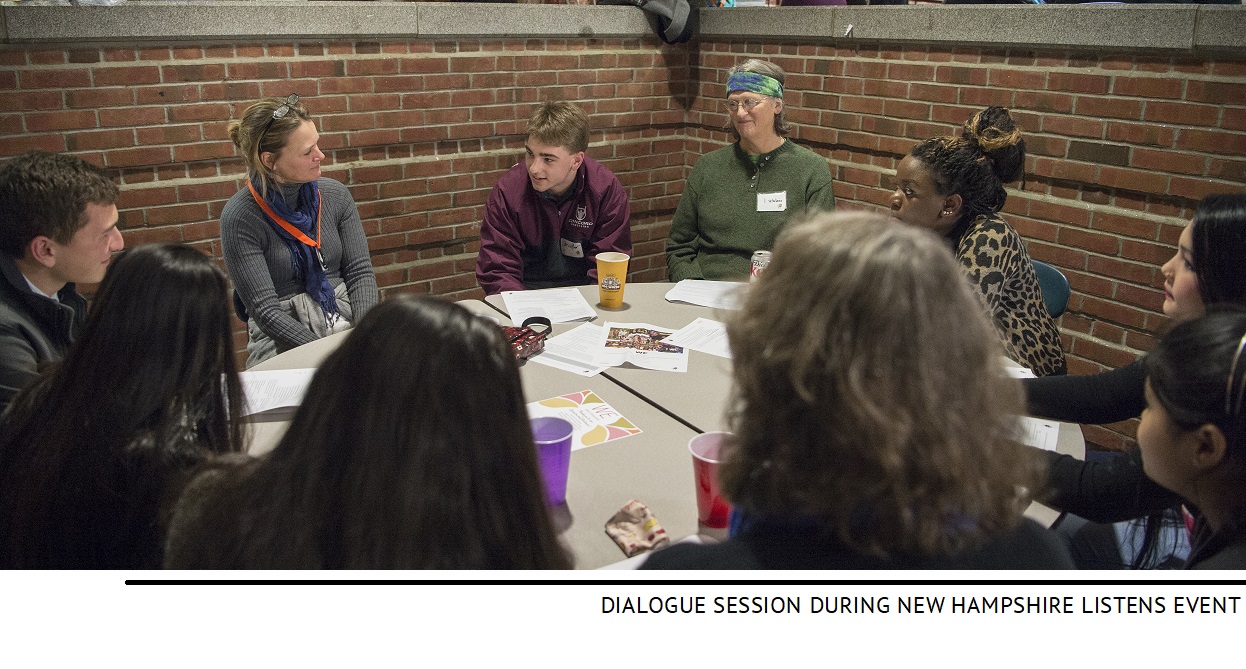

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and other communities across the state, Everyday Democracy Anchor Partner New Hampshire Listens, and its affiliate Portsmouth Listens, recruit volunteer facilitators to host multiple dialogue sessions, often in their homes and on consecutive weeks, and to guide their small groups towards consensus on a local issue. Portsmouth’s process involves volunteers from the get-go:

Portsmouth Listens volunteers and city officials form a Steering Committee drawing together stakeholders in the question or issue. This committee frames the dialogue question to be given to the study circles. For example, ‘How do we balance the tax burden and level of services needed to make Portsmouth the best place to live and work for everyone?’…Portsmouth Listens recruits and trains neutral facilitators and develops a study guide for the four two-hour sessions that the study circles will deliberate….Citizens in the small groups or Study Circles deliberate for two hours a night over four weeks to answer the question….The individual Study Circles write their conclusions in a report, and present their findings. The reports are presented to relevant government bodies (city council, planning board, etc.) in person, and their written reports are published in the newspaper.

Building on New Hampshire’s Model, in Austin, “Conversation Corps” has recruited and trained hundreds of volunteers to host dialogue throughout the city on topics recommended by the City of Austin, the Austin Independent School District, and the public transit agency, Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Through carefully designed discussion guides, volunteers could give participants an overview of the topic and some background statistics and pose specific questions that agencies felt would yield information helpful to their policymaking. As Austin transitioned into a single-member district City Council, with ten members representing districts instead of six members elected at-large, conversations in all ten districts helped better connect voters to their elected officials and gave a more accurate picture of public opinion across the city. To date, more than 200 volunteers completed training.

Building on New Hampshire’s Model, in Austin, “Conversation Corps” has recruited and trained hundreds of volunteers to host dialogue throughout the city on topics recommended by the City of Austin, the Austin Independent School District, and the public transit agency, Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Through carefully designed discussion guides, volunteers could give participants an overview of the topic and some background statistics and pose specific questions that agencies felt would yield information helpful to their policymaking. As Austin transitioned into a single-member district City Council, with ten members representing districts instead of six members elected at-large, conversations in all ten districts helped better connect voters to their elected officials and gave a more accurate picture of public opinion across the city. To date, more than 200 volunteers completed training.

Additionally, models like the “meeting in a box” utilized in multiple cities and “Text, Talk, Act,” a project of Everyday Democracy and several other partners, drew upon the energy of volunteers to bring topics that would have been discussed at a public meeting into their circles of friends, community organizations, and the like. These self-facilitated discussions did not require host training or volunteer coordination as much as a willingness on the part of the initiating participant to report group findings back to the sponsoring entity at the conclusion. In an evaluation of the Text, Talk, Act dialogue on mental health, a study found:

participating in Text, Talk, Act leads to an increase in participants’ ability to recognize a peer in need, ability to reach out to a peer in need, ability to talk about the topic of mental health, likeliness to seek additional information, and likelihood to implement information or skills from TTA. Furthermore, participants reported positive experiences based on the technology used by TTA, clarity of TTA purpose, and the relevancy/usefulness/quality of TTA content. These satisfaction indicators support the participants’ likelihood to recommend TTA to others…Also, when participants were asked, ‘what are the best ways to engage youth on the topic of mental health,’ TTA was voted to be the third most effective or popular method (after face-to-face conversation and social media).

Countless other examples exist of volunteers contributing to the work of public engagement, but this brief overview illustrates various ways in which those charged with engaging the public can multiply their forces and improve their reach into their target populations. While volunteers may lack the time and expertise that public engagement professionals bring to the table, they can entice those disinclined to participate to change their minds, and they can bring about a revolution in the ways the public engages.

Larry Schooler is a mediator, facilitator, and public engagement consultant and senior fellow at the National Civic League and the Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at the University of Texas at Austin. His work has appeared in newspapers, Governing magazine, the Huffington Post, National Public Radio, and Voice of America. He lives in South Florida with his family.