In 1878, a young New York attorney named William Dudley Foulke, moved to Richmond, Indiana, to open a law practice. Founded by abolitionist Quakers, Richmond had been an important stop on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War. After the war it was home to Earlham College, a center of Quaker religious thought, and the “Richmond School,” a celebrated group of American impressionist painters.

In 1878, a young New York attorney named William Dudley Foulke, moved to Richmond, Indiana, to open a law practice. Founded by abolitionist Quakers, Richmond had been an important stop on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War. After the war it was home to Earlham College, a center of Quaker religious thought, and the “Richmond School,” a celebrated group of American impressionist painters.

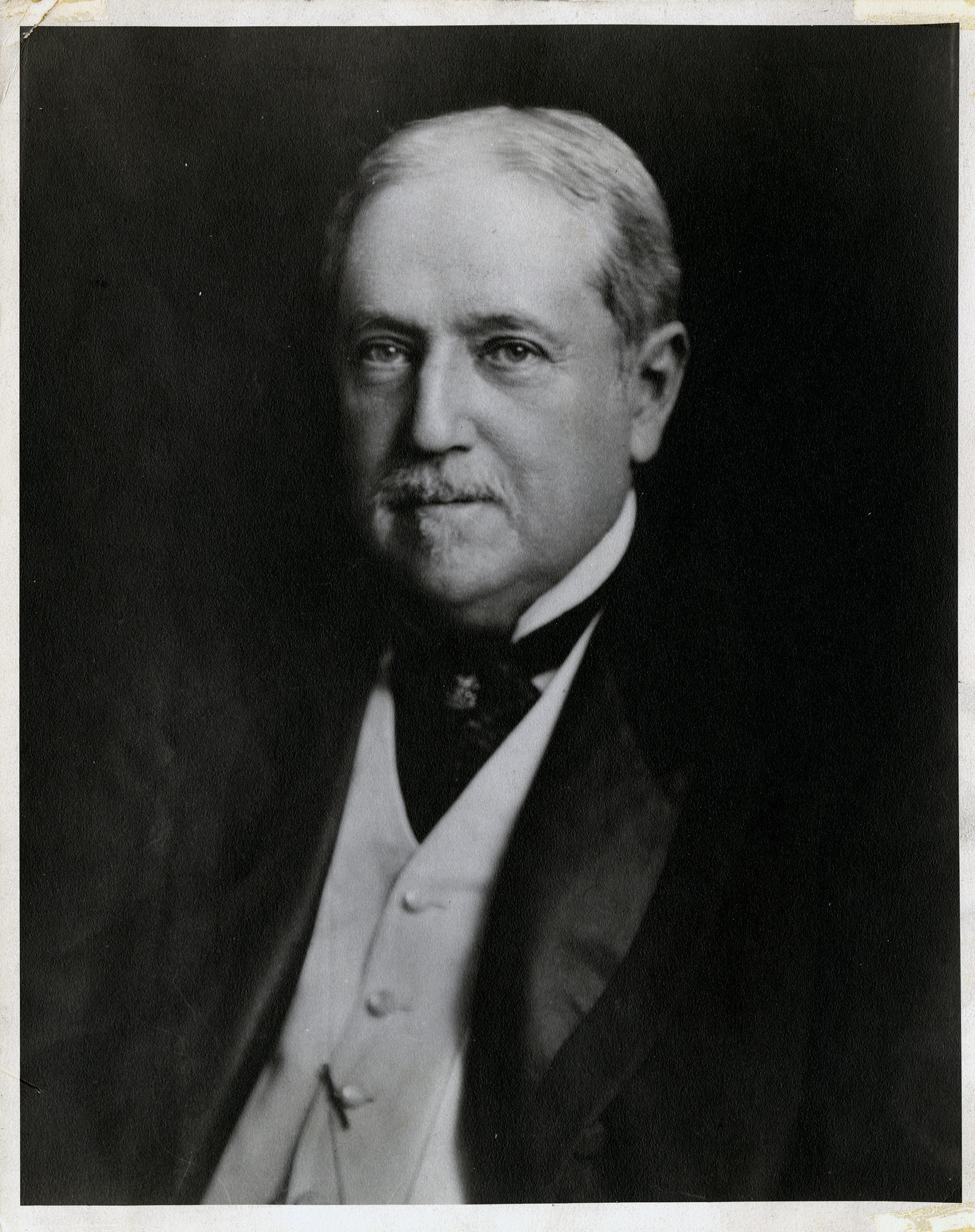

Foulke, who had been raised in the Hicksite tradition, a strain of Quakerism that emphasized religious liberty and a strong sense of personal duty, quickly became immersed in the cultural and political life of the small midwestern city with a large social and cultural footprint.

In 1882, he ran for the Indiana Senate and was elected to represent Wayne County on the Republican ticket. One of his first duties was to chair an investigative committee looking into allegations of corruption and cruelty at a state-run asylum for the mentally ill.

The mental hospital had been staffed with patronage-seekers and supporters of the political machine that had proposed the bill that funded the institution. One state senator secured jobs for his daughter, a nephew, three nieces and a number of friends. There were no tests or background checks to determine the fitness of employees of the asylum.

“The character of the attendants procured by this political system was so bad that acts of neglect and cruelty were frequent,” wrote Foulke in his autobiography. “Visitors to the asylum saw patients slapped severely, struck with the fist, shaken, kicked, dragged by the neck and teased both by attendants and by their fellow patients in the presence of attendants who did not interfere.”

A long struggle between supporters of the hospital’s corrupt board of trustees and would-be reformers ensued, and eventually the crooked trustees were removed. In 1895 the state “benevolent” institutions were placed under the control of a nonpartisan commission.

Foulke later emerged as leading national advocate of the “merit system” for hiring and promoting government employees. In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to the U.S. Civil Service Commission. His commitment to ethics and professionalism in the public sector brought him into the orbit of the National Municipal League (the original name of the National Civic League), an organization founded to serve as a clearinghouse for new ideas about local governance.

The historian Richard Hofstadter once wrote that the Progressive Era was a time when “almost every aspect of American life…was being reconsidered.” Between 1900 and 1920, four constitutional amendments were adopted, including the 17th Amendment (the direct election of Senators) and the 19th Amendment (women’s suffrage). The first food safety regulations were adopted, as well as anti-trust legislation, the popular initiative and the recall of elected officials.

One of the most active (and least remembered) reform leaders during those years was Foulke, who served as president of the National Municipal League from 1910 until 1915. An attorney, author, translator and state senator, Foulke developed friendships with the era’s leading social and political reformers, including Theodore Roosevelt, Julia Ward Howe and Jane Addams.

Foulke’s passion for reform causes encompassed every issue from women’s suffrage to proportional representation. He was one of the leading advocates for freedom and democracy in Czarist Russia and an outspoken critic of the Ku Klux Klan.

In his youth, Foulke helped organize the Young Men’s Municipal Reform Association in New York City, where he was active in efforts to fight the corrupt political machine of William M. Tweed.

He experienced political corruption firsthand while serving as an election observer. When the vote came in, the Tweed-backed candidate had fewer votes, but the precinct’s chief election officer reversed the tally. “This was done in a perfectly mechanical way,” he later observed, “as if the conclusion was a matter of course, and not one of the election officers appeared to notice it.”

During his tenure as president, the National Municipal League published the Model City Charter of 1915, a revision of the organization’s proposals for local governance that was three years in the making. It was a major departure from the League’s original model, which recommended a powerful mayor with executive duties.

The bones of the new form of government—non-partisan elections, a small council and an appointed manager with professional training—are still elements of the League’s Model City Charter, which is currently in its eighth edition. Thousands of U.S. cities have adopted this model of governance.

Foulke’s lifelong service included terms as president of the Proportional Representation League, the American Woman Suffrage Association and the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom. He helped organized the League to Enforce Peace, a precursor to the League of Nations, and served on the platform committee of the short-lived Progressive Party.

Foulke represents a strain of progressivism that has been largely forgotten or misunderstood by modern critics from both the left and the right. According to a stereotype embraced by many historians and political thinkers, municipal reformers of the Progressive Era were middle class moralists who adopted a “corporate vision” of local governance that consolidated the power of business groups at the expense or working class and immigrant voters.

Of course, some supporters of municipal reform did fit the stereotype, but not Foulke. His lifelong commitment to progressive causes combined a staunch advocacy of ethics and professionalism in government with a deep concern for the plight of the oppressed.

For instance, in the early 1920s, when the Ku Klux Klan emerged in the Hoosier State as an anti-immigrant organization with a mass base of supporters that included mainstream religious and political leaders (for instance, the governor and half the state legislature), Foulke was outspoken in his opposition to the hate group.

Because of this opposition, the elderly reformer received an anonymous letter, which ended with this threat. “Now unless you cease your activity you will receive a good flogging! The fiery cross is here to stay!”

In 1925, the state’s “Grand Dragon,” D.C. Stephenson, was convicted of raping and murdering a schoolteacher. The publicity surrounding the grotesque crime and the sensational trial led to the demise of the Klan in the Midwest.

Foulke, who never did receive a flogging, lived long enough to see the Klan’s popularity evaporate. He died in 1935 at the ripe old age of 87.

For readers interested in the history of American political reform and the National Civic League, Foulke’s memoir, Fighting the Spoilsmen: Reminiscences of the Civil Service Movement, is well worth reading.