By George Holcomb, with help from Layne Ragsdale, Kevin Cheri, Jeanette Fitton and Beth Ardapple.

In 2002, a visiting football team stopped off at a local McDonald’s after playing a game at Harrison Junior High. It was Halloween, so the restaurant was running a special; free ice cream cones for people who showed up in costume.

A young person came in draped in a sheet, as a ghost, to collect a free cone. Some visiting athletes of color mistook the costume for a Ku Klux Klan robe, including one young player who was discovered hiding in the corner of the men’s room, quaking with fear. His friends quickly gathered the rest of the team together and hit the road.

A newspaper in Fayetteville published a letter from an adult who traveled with the team about the dangers of visiting Harrison. The local newspaper in Harrison didn’t publish it, but citizens knew about and talked about the letter.

Most of the reaction in Harrison went like this: “Why would anyone react like that? What made this young person believe that this was a dangerous place?”

Harrison Mayor Bob Reynolds heard these questions as genuine, and he understood some of the background of the town’s troubled racial history. He knew about the early 20th-century violence that drove more than one hundred Black citizens (leaving only one) from the town. He knew the outsized media presence of area white supremacist entities, including a family that claimed to be the leaders of the Ku Klux Klan.

To answer this and other questions, Reynolds convened the Harrison Community Task Force on Race Relations. “We originally thought it would take about six months,” recalled Layne Ragsdale, who joined the task force in 2003 when she was president of the local chamber of commerce. Twenty years later, the task force is still going.

Harrison’s Sixth annual MLK commemorative candlelight vigil with the Arkansas MLK Commission.

Harrison has long been an important economic hub for the region, but that was changing with the times, and the town’s reputation was part of the problem. Tourists would no longer stop for gas when passing through. Employers had a hard time moving employees to Harrison. Franchises didn’t want to invest in a town considered racist. “America is becoming more diverse and more connected all the time. We were paying a price for being perceived as outside the current of America,” said Ragsdale.

“Of course, the most important issue was whether we could be proud of our town as a community of kindness, good will, and inclusion,” she added, “but there was a pragmatic question as well. We had to address this issue because it was affecting our pocketbooks.”

In March 2003, the formation of the task force was announced in the local newspaper, and members of the community began to take an interest in the group’s work. The task force meetings were open to the public and reported in the local newspaper. But within a few weeks, a group of white supremacists came to a meeting and argued that the town’s reputation for hostility to people of color was “a good thing.”

“Like many white people, I thought racism was a lingering vestige of the past and would disappear with time,” said Ragsdale. “I thought the noisy Klan family out in the county was a foolish irritant that had no impact or influence on Harrison.”

Ragsdale said the encounter opened her eyes. The task force gathered information about the seven men who had come to the meeting to “educate” them. Six had retired to Harrison because of its racist reputation. “I realized the false image repelled the people we hoped would move here,” she said. “But it did more than that. It attracted people who weren’t going to help us move forward. “If we didn’t do something, we would soon become the racist place those young football players feared. Community survival depended on our understanding and action.

A Troubled History

A small city in the Ozark Mountains, Harrison was the site of two major race riots during the early twentieth century. After its Black residents were driven out, it joined the ranks of America’s growing list of “sundown towns,” municipalities where people of color risked becoming victims of mob violence if they remained after dark. Harrison was far from unique. There were thousands of sundown towns and counties during and after the Jim Crow years. But Harrison developed an outsized reputation for racism in part because of events that were beyond the control of local leaders and community members. In late 1990s, a man who lived in another Boone County town emerged as a national leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. His presence and a series of provocations by area white supremacists garnered media attention. News outlets took to calling Harrison, “the most racist town in America.”

It’s a label that Harrison residents such as Kevin Cheri have been working hard to dispel.

“Few communities take a good long critical look at themselves and look for ways to correct and improve themselves,” said Cheri, a member of the Harrison Community Task Force on Race Relations. “Most wait until something horrible happens before recognizing the need to address racism in America. Citizens of Harrison have become proactive in applying national discussions to their small-town community, making a difference one step at a time.”

Years ago, when Cheri was offered a park ranger position at Harrison’s Buffalo National River, he was told, “You will be the only Black person within a fifty-mile radius of the park.” Being a young, naive, recent college graduate, he jumped at the opportunity to start a career with the federal government despite the area’s demographics. Until he later came across police reports describing threats against his life by locals, he had no idea how unsafe he was. One threat implied that someone would kill him, saying, “He won’t last long.”

Cheri had been on the job a few months when he made that discovery. He decided that if he was careful, professional, and respectful, he would be okay. Other than having his car tires slashed once, Cheri said, he enjoyed two and a half positive years at the park. He felt well-accepted locally and experienced no other blatant acts of discrimination. He also realized the positive impact his presence had in dispelling many stereotypes and negative impressions of minorities, especially Blacks.

Twenty-seven years later, Cheri moved back to Harrison to accept the Buffalo National River Superintendent’s position. Now married and raising children, he was careful in weighing his decision to return to Harrison, but park service associates and friends still living in the area convinced him his family would be safe. Soon, Cheri and his management team began to achieve success in recruiting other minorities.

In 2012, Cheri joined the Task Force on Race Relations. “The commitment of these community volunteers to stand up to racism in their town, and to battle an exaggerated label was impressive,” he said. “I admired their pursuit of change despite significant pushback from other community members, family, and friends who felt talking about it would only make matters worse. I felt a responsibility to share my experience, to help the community that welcomed me and my family. This seemed like a golden opportunity to help something good happen.”

A Chronology of Task Force Activities

2003

In January articles and an editorial were published in the Harrison Daily Times placing the issue of race before the community. In March came the announcement of the formation of the task force. In May, a National Day of Prayer was observed in Harrison’s downtown square to demonstrate unity.

2004

Task force member Scott Hoffmann produced “Silent No More,” a video featuring prominent community members announcing anti-racism actions and intent.

2006

The task force took out a double full-page spread in the Daily Times denouncing racism, signed by more than 700 residents. The city council passed a resolution denouncing racism. A documentary called “Banished” told the story of three communities, including Harrison, that violently ejected their Black residents, and the task force hosted showings and discussions of the film with clergy, business leaders and students.

2007

Task force members participated in the 50th anniversary of the integration of Little Rock High School, including an advertisement in the celebration magazine, local posters and a free showing of “The Ernest Green Story,” a documentary about one of the Little Rock Nine, the Black students who integrated the high school. A Harrison student won the Little Rock Nine essay contest.

2008

High School seniors in Harrison formed a Diversity Council. The book Buried in the Bitter Water: The History of Racial Cleansing in America by Elliot Jaspin includes Harrison. The task force hosted a showing, with discussion, of the “Mississippi Innocence” documentary about two Black men found to be innocent after spending a total of 32 years in jail. The men, their families and the producers all attended and received a standing ovation at the end.

2010

The task force hosted the National Council for Community and Justice, which provided community training.

2011

A Harrison area jury was the first to convict a defendant under the 2009 Federal hate crimes law.

2012

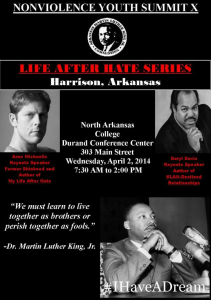

The Non-Violent Youth Summit was held in Harrison, organized by the Arkansas Martin Luther King Jr. Commission.

2013

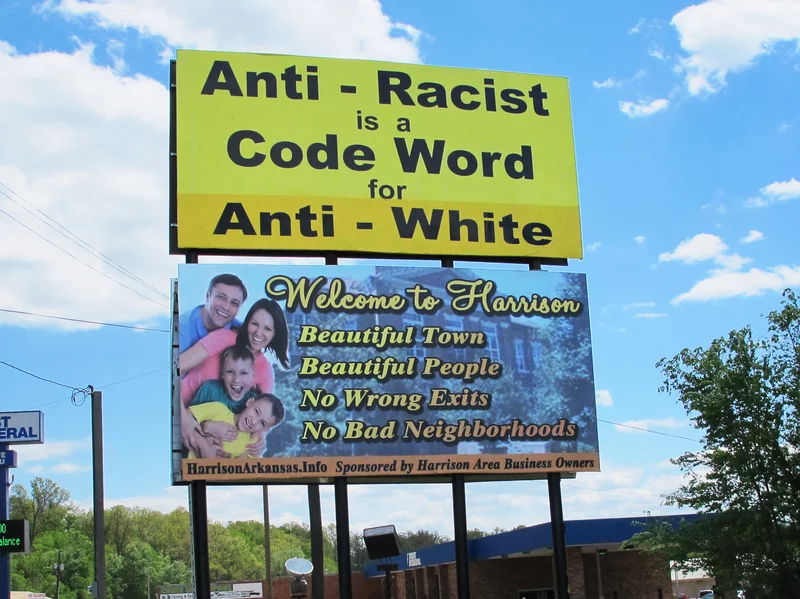

When area white supremacists put up two billboards in Harrison, including one that said “Anti-racist is a code word for anti-white,” the task force and the community responded in the press, picketed the sign, and started the “Love your Neighbor” campaign with billboards, t-shirts, and yard signs. The singer/songwriter David LaMotte was brought to Harrison by the Rotary Peace Forum as a part of the campaign.

Racist billboards prompted the Task Force to launch a city-wide ‘Love Your Neighbor’ campaign.

2014

Task force member Carolyn Cline put up a display “Harrison 1900 to 1909” at the local library with photos of Black Harrison residents, maps of where they lived and worked as well as the history of racial expulsion during that period. In March, the group held a Love Your Neighbor Day honoring members of the Fire and Police services with food and activities at Minnie Harris Park as a response to a proposed White Man’s March by the white nationalists.

Burying Racism in Harrison, a ceremony conducted during the 2014 Unity in the Community Fall Festival.

2016

The task force received the Dream Keeper Award from the Arkansas Martin Luther King Jr. Commission at the MLK Jr. Day celebration. In April, comedian W. Kamau Bell’s CNN series, the United Shades of America, featured Harrison and the task force in the first episode. Bell later received an Emmy Award for the series.

Task Force members and Harrison Mayor pose with Dream Keepers Award.

2017

Harrison Mayor Dan Sherrell publicly denounced hatred, bigotry, and white nationalism after the Charlottesville riots. Harrison citizens signed commitment cards pledging to stand in support of the people of Charlottesville against racism and bigotry. Mayor Sherrell gathered the commitment signatures and forwarded them to the Charlottesville mayor.

2019

Local lawyers worked with landowners to fully understand their property rights and how they could legally prevent racist billboards from being erected on their properties. The only racist billboard still standing in the Harrison area was installed by Harrison Sign Company on land owned by their president, Claude West. Neither West nor his business partner, David Frye, live in the Harrison area.

2020

A video of a white man being shouted at in Harrison for holding a “Black Lives Matter” sign went viral. In September the city, chamber and county leaders passed a resolution denouncing racism and forming the Diversity and Inclusivity Committee to identify opportunities and develop initiatives to promote diversity and inclusivity in the community. Various articles and television interviews occurred as the press began to acknowledge Harrison as a community dealing with its racial history and present racist reputation.

Also in 2020, the Harrison Regional Chamber of Commerce added diversity goals to its strategic plan and a diversity web page to its site. In November, after COVID cancellations of planned in-person events, the task force, mayor, and Arkansas Martin Luther King Commission held a virtual conversation about race relations with Bernice King, the daughter of Martin Luther King Jr. and the CEO of The King Center in Atlanta.

Learnings

Some of these activities were highly successful, while others less so. For instance, it took five years before racist billboards began coming down, and one remains. But looking back over the task force’s history, Layne Ragsdale has identified five major takeaways:

- Take the time to define your mission clearly and stick to it.

“It took months for us to define what we were trying to do,” she said. Most of our group were faith leaders, and I teased that they certainly had an eternal timeframe. But it was essential to spend the time to get it right, and we haven’t changed our focus in twenty years.”

- Relationships and allies are everything.

One of the task force’s most important allies was the Arkansas Martin Luther King Commission. Members of the commission reached out to the task force, and the relationship has deepened over the years. Task force members have marched in the Commission’s MLK parades, attended its Juneteenth celebrations, traveled to Atlanta for training at the King Center, and partnered with them in 3 youth summits, two of which Harrison hosted.

Arkansas Martin Luther King Commission’s Executive Director DuShun Scarborough receives Keys to the City of Harrison 2021.

In 2020, the MLK Commission accepted the Harrison Chamber of Commerce’s membership invitation. In laying the groundwork for that offer, the task force engaged business leaders, political office holders and candidates, law enforcement, schools, and residents.

“These events happened in a community that has been labeled ‘the most racist town in America,’ a politically conservative, rural town that people of color have avoided for a hundred years because of its reputation,” said commission director Dushun Scarbrough.

“It shows America what is possible.”

Task Force members talked to every city office candidate about the importance of the city’s image. Realtor Jerry Jackson took an interest early on, and years later, when he became mayor, he shepherded the community through Black Lives Matter marches and racist billboard messages. He utilized task force members and the Arkansas MLK Commission as a sounding board when he needed to think through problems.

Harrison hosted 3 Black Lives Matter protests and marches that were peaceful and generated support.

Harrison pastors were founding members of the task force. Early on the group reached out to an AME church in Helena, Arkansas (250 miles away), engaging with the parishioners there and helping with work on repairing the church building.

When the local community college sought to host a regional championship tournament, several coaches nixed Harrison. They didn’t want to subject their players to a town with Harrison’s reputation. Task force members stepped in and made their case to the site selection committee, pleading with them to reconsider. When those appeals succeeded, the task force organized volunteers to greet players with small gifts and warm welcomes. Members talked to local restaurant owners to make sure visitors felt welcomed.

- Never do anything that would prevent an adversary from becoming an advocate. Ugly actions or angry rhetoric breaks communication and can embarrass our community and allies.

All of us live on a spectrum of cultural competency, defined as the ability to understand, appreciate, and interact with people from cultures or belief systems different from our own. We can find unlikely allies in unusual places if we take the time to interact with respect.

During its early days, the task force was invited to address a local Sons of Confederate Veterans meeting. They assumed the group would be opposed to the task force. Instead, task force members found a group with a clear understanding of the damage caused by white supremacist falsehoods and the misrepresentation of symbols – the very things we were learning.

“Here was a group of people who understood the issues better than we did!” said Ragsdale. The task force also learned more about the group’s mission of honoring military veterans and documenting Civil War activity in the Missouri/Arkansas border area, where the war’s impact was deep and personal.

“Military service is highly respected in our community. Once we understood their mission, it opened up a path to work together,” said Ragsdale. “We have even done media interviews together. They help us respect the facts of history without the fanaticism of the white nationalist movement.”

- Emotions, not facts, move people. Movies, shared events, and personal stories are powerful tools as people learn to understand, appreciate, and interact with people from different cultures or belief systems.

Like thousands of similar small communities, Harrison struggles with a simple fact; it doesn’t provide as many occasions for cultural interaction as in larger, more diverse places. “We’re learning,” Ragsdale said, “so we work hard to do music exchanges, bring in ball teams, hold youth summits, and try to provide our students with experiences that would be common in a more diverse setting.”

“If you want to advance cultural competence in the community, you must be very intentional,” she added. “You need to make a plan and stick with it. Films, documentaries, speakers, and musical events can touch peoples’ emotions, to move them forward in cultural competency.”

- Don’t give up. Lasting change takes time and things will occasionally go badly. Perseverance brings progress and lasting change.

Members consistently look for opportunities to engage. Sometimes it goes well, sometimes it goes wrong, but the willingness to be vulnerable to making mistakes and being criticized is a measure of commitment to the task force’s goal: “a cohesive, warm community [for] all people of peace and goodwill, regardless of race.”

“I believe for a town of our demographic and culture, we have done more than anybody would have expected,” Ragsdale said. “As a community, we’re trying to address racism by learning and educating ourselves.

“There will always be critics. When we started, many people felt we were making a bigger issue than warranted. They said we were just creating more problems. Today, people say, ‘Well, are you doing enough? Why isn’t this fixed? We’ve gotta do better. Why aren’t you doing more?’ That’s a good problem to have.”

George Holcomb is the Secretary of the Harrison Community Task Force for Race Relations.

Layne Ragsdale is a Founding Member, Co-Chair and Public Relations Officer of the Harrison Community Task Force for Race Relations.

Kevin Cheri is a member of the Harrison Community Task Force for Race Relations and a former Buffalo National River superintendent.

Jeanette Fitton is a Social Media Officer and Co-Chair of the Harrison Community Task Force for Race Relations.

Beth Ardapple is a member of the Harrison Community Task Force for Race Relations.