By Shayne Kavanagh and Jake Kowalski

In a time of budget cuts, it is almost inevitable that services will suffer. By taking equity into account, a local government can reduce the pain experienced by disadvantaged parts of the community and reduce the pain experienced by the community as a whole.

Many local governments are taking an interest in “equity” in budgeting. But what does that mean, and how can it be put into practice?

What Is Equity?

It helps to draw a distinction between equity and equality. Equality means treating all people the same. Equal treatment of all constituents has been a long-standing aspiration of local governments. The emphasis on equal treatment arose from a desire to combat the corruption and favoritism that was prevalent in local government in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Most people would consider it wrong to distribute local government resources according to family background, personal connections, or political affiliation, but this was once a common a practice. The push for equal treatment addressed this problem by calling for everyone to get the same resources.

Equal treatment is also a moral imperative for some local government services. For example, the 14th Amendment states that all people should be treated equally in the justice system.

Though equality is a time-honored and important principle in a democratic system, it is not perfect. There are cases where the principle of equity has much to offer. Equity means people could be treated differently in the interest of giving all people access to health, safety, and welfare (the fundamental purposes of local government). Exhibit 1 is a popular depiction of the essential difference between equity and equality. Let’s now further explore this concept, both why it is coming the forefront now and practical concerns and challenges.

Exhibit 1: Equality versus Equity

Photo Credit: State Dept./Doug Thompson

Why Is Equity Coming to the Forefront Now?

Just as the principle of equality gained currency in public management in the early 1900s in response to conditions of the time (pervasive corruption), the principle of equity is coming to the forefront today because of pervasive and material differences in wealth, safety, and health, particularly along racial lines. For example, the United States has the highest level of income inequality among the top seven largest industrialized democracies.1 This is true regardless of race, but the problem is exacerbated when race is taken into account. For example, the income gap between Black and White people has remained essentially unchanged since 1970.2 The disparities become even more pronounced when looking at the wealth gap. In 2016, the net worth of a typical White family is almost ten times larger than that of a typical Black family.3

This is important because the United States is a democratic country where popular support for our system of government is premised on, in no small part, “the American Dream.” Though there is no universally accepted definition of the American Dream, the opportunity for prosperity, success, and upward mobility are part of what the American Dream is generally held to include. Education, public safety, and essential services provided by local government support people’s ability to pursue the American Dream. If people don’t have equitable access to these services, it would be hard to argue that they have equitable access to the American Dream.

What Are the Practical Concerns with Equity in Budgeting?

A fundamental tension between equality and equity has to do with fairness. Perceptions of fairness are essential to any decision-making system—without it, the system will likely fail. One of the great advantages of equality as an organizing principle for budgeting is that it provides a simple and straightforward definition of fairness: everyone is treated the same. Equity brings a different perspective to fairness, one that is more nuanced. With this nuance comes practical concerns about measurement and allocation of resources.

For example, let’s take another look at Exhibit 1. It implies that as long as all the flowers make it over the fence, success has been achieved. However, real life is often not so clear. Consider schools teaching children to read. Imagine the fence represents reading at grade level. Now imagine that the tall flower represents a talented and/or hard-working child who would exceed the standard with the given level of support. Is it acceptable to remove the support so that child now only reaches the standard, for the sake of giving extra support to another child?

Another conundrum posed by Exhibit 1 is the redistribution of resources. Imagine our flowers paid taxes (local governments can only wish). Imagine it is a leaf-tax, where some amount is paid for each leaf. Would the taller flower be pleased with an outcome where it pays more in taxes yet gets less support and ends up with the same amount of sun as everyone else? The situation might not be so different with a wealthier taxpayer who feels they aren’t getting adequate value for their contributions to the local government budget. Psychological experiments show that people who feel they aren’t getting an adequate return from their participation in a shared resource (like a local government) will look to withdraw their participation.

Finally, Exhibit 1 does not explicitly distinguish between equity in opportunity and equity in outcomes. Put another way, is equity intended to “level the playing field” or “even the scoreboard”? This difference is critical for two reasons. First, the type and scale of government intervention in the community would differ dramatically, depending on the government’s goal. Second, any time government proposes to change the scoreboard, hard questions about fairness may soon follow—especially where a citizen’s own agency has an important impact on the extent to which they achieve the outcome in question and where government intervention may be seen as overreach into private affairs.

Fortunately, there are strategies for addressing these concerns when applying the equity lens to budgeting.

Applying Equity in Budgeting

Let’s start with an illustration of how the difference between equity and equality might be applied. The mobility of the population is important to people for accessing economic opportunities. The condition of the road system supports mobility. An equal system of funding would fund road repair at the same level in every area of the community. An equitable system would allocate more funding where poor road conditions are most impeding people’s access to economic opportunity. This approach gets everyone the road system mobility they need to realize economic opportunity.

The equity principle can help us look even deeper and question if the public budget is best spent on road repair to enhance people’s mobility. For example, one city found that a neighborhood with a predominantly Black population had higher traffic fatalities, although the pavement conditions were acceptable. The budget was therefore used for enhanced traffic controls instead of improving pavement quality. Another city found that in a working-class neighborhood, people relied more heavily on the bus system to get to work. Reaching the bus stop in the winter can require walking through a great deal of snow. Therefore, the city devoted extra resources to clearing the sidewalks of snow in that neighborhood. This gets everyone the resources they need for mobility without making anyone worse off.

The equity principle can help us look even deeper and question if the public budget is best spent on road repair to enhance people’s mobility. For example, one city found that a neighborhood with a predominantly Black population had higher traffic fatalities, although the pavement conditions were acceptable. The budget was therefore used for enhanced traffic controls instead of improving pavement quality. Another city found that in a working-class neighborhood, people relied more heavily on the bus system to get to work. Reaching the bus stop in the winter can require walking through a great deal of snow. Therefore, the city devoted extra resources to clearing the sidewalks of snow in that neighborhood. This gets everyone the resources they need for mobility without making anyone worse off.

These examples show how the equity principle can be applied to a few specific situations. But how can equity be applied to budgeting more systematically?

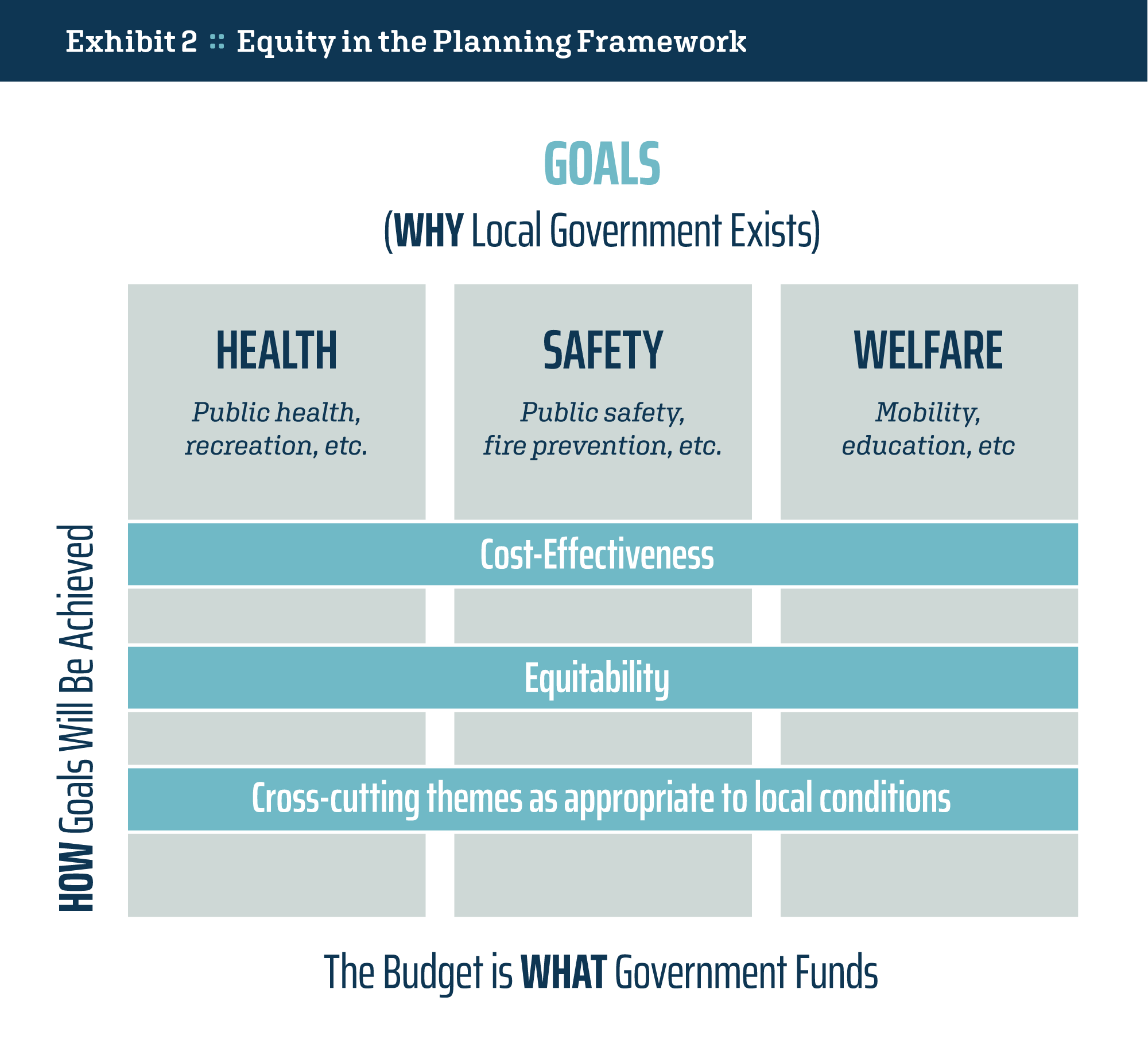

First, let’s recognize that budgeting will be most effective when it is preceded by planning. For example, it is a long-standing GFOA best practice that a budget should be linked to a strategic plan. Exhibit 2 shows a basic representation of a planning framework. A local government has goals that describe why government exists in the first place. In Exhibit 2, we have used the goals of health, safety and welfare to correspond with the basic purposes of local government, but each local government will have its own goals.

Next, the exhibit shows cross-cutting themes that describe how the goals will be achieved. It includes “cost-effectiveness” an example of a theme that all local budgeteers should recognize. Equitability is another such theme. Exhibit 2 shows that not only should local government define the goals it will work toward, but also that how it achieves those goals matters. It is not enough that some people experience health, safety, and welfare—all people must.

Exhibit 2: Equity in the Planning Framework

A number of governments have established consensus around goals that define why the local government exists, often as part of a strategic planning process. Fewer have achieved consensus around equity as a cross-cutting theme. A thought experiment that can help build consensus for equity is called “the veil of ignorance.” It can be used when designing any kind of system, such as a local government’s budget and the public services that it funds. This thought experiment asks us to use our imaginations to place ourselves behind a veil of ignorance where we know nothing of ourselves or our positions in society—in other words, imagine that we don’t know characteristics like our own sex, race, income, place of residence, and so on. We then design the system from behind this veil of ignorance. When people imagine that they don’t know these characteristics about themselves, they tend to want a system (budget) that is fair, no matter what characteristics they find themselves with when the veil is lifted. Therefore, if we find that people are disadvantaged by their race or socio-economic class, we’d want a system that mitigates those disadvantages.

After establishing a consensus on the goals and the cross-cutting themes, the local government can find where there are opportunities to do better. This starts by deciding how to measure the goals. For example, if public health is a goal, then maternal and child health, as measured by percent of pre-term births, could be a measure. Or if mobility is a goal, then walkability of neighborhoods could be a measure.

Next, the local government can check to see if there are important differences among groups on the measures, currently. Local governments that have had the most success with equity in budgeting have found that it is important to focus equity efforts on a few specific groups. Race and socio-economic class are usually the most relevant groupings to consider. And geography often correlates with race and/or socio-economic class. For example, perhaps a neighborhood with poor walkability also has lower income residents.

With this information, a local government can better think about what it might fund differently, via the budget process.

This thought process can be guided by five interlocking principles that help local governments avoid the potential for perceptions of unfairness and other concerns associated with equity.

Avoid creating zero-sum competitions. A zero-sum competition is where one person can only win if another person loses. Exhibit 1 implies a zero-sum competition is inherent in equity, but our examples of equity in mobility show that is not necessarily true.

Avoid either/or thinking and encourage both/and thinking. Exhibit 1 and our example of children and reading at grade level implied that we might have to choose between either helping talented/hardworking children or disadvantaged children. Some educators have recognized that this is false choice, and it is possible to support both talented/hardworking children and disadvantaged children at the same time. For example, personalized learning is a strategy where students are provided with content and exercises that are tailored to their ability. “Both/and” thinking is more difficult than “either/or” thinking, but there are structured and proven ways to encourage it. For example, the earlier side bar described how an equitable strategy for road repair would actually be a more cost-effective approach for the entire community. The road repair example reveals that thinking about how equity can prevent problems from occurring in the first place (e.g., roads deteriorating too far) is a powerful way to make equity a “win-win,” rather than a “win-lose” proposition.

Create procedural justice. The reality is that not everyone can get 100 percent of what they want from a budget. However, if people feel the process used to reach budget decisions was fair, they are much more likely to be willing to live with the outcomes. Procedural justice requires that decision makers are doing their best to be objective, that the process is transparent, and that people are given the opportunity for input and are taken seriously.

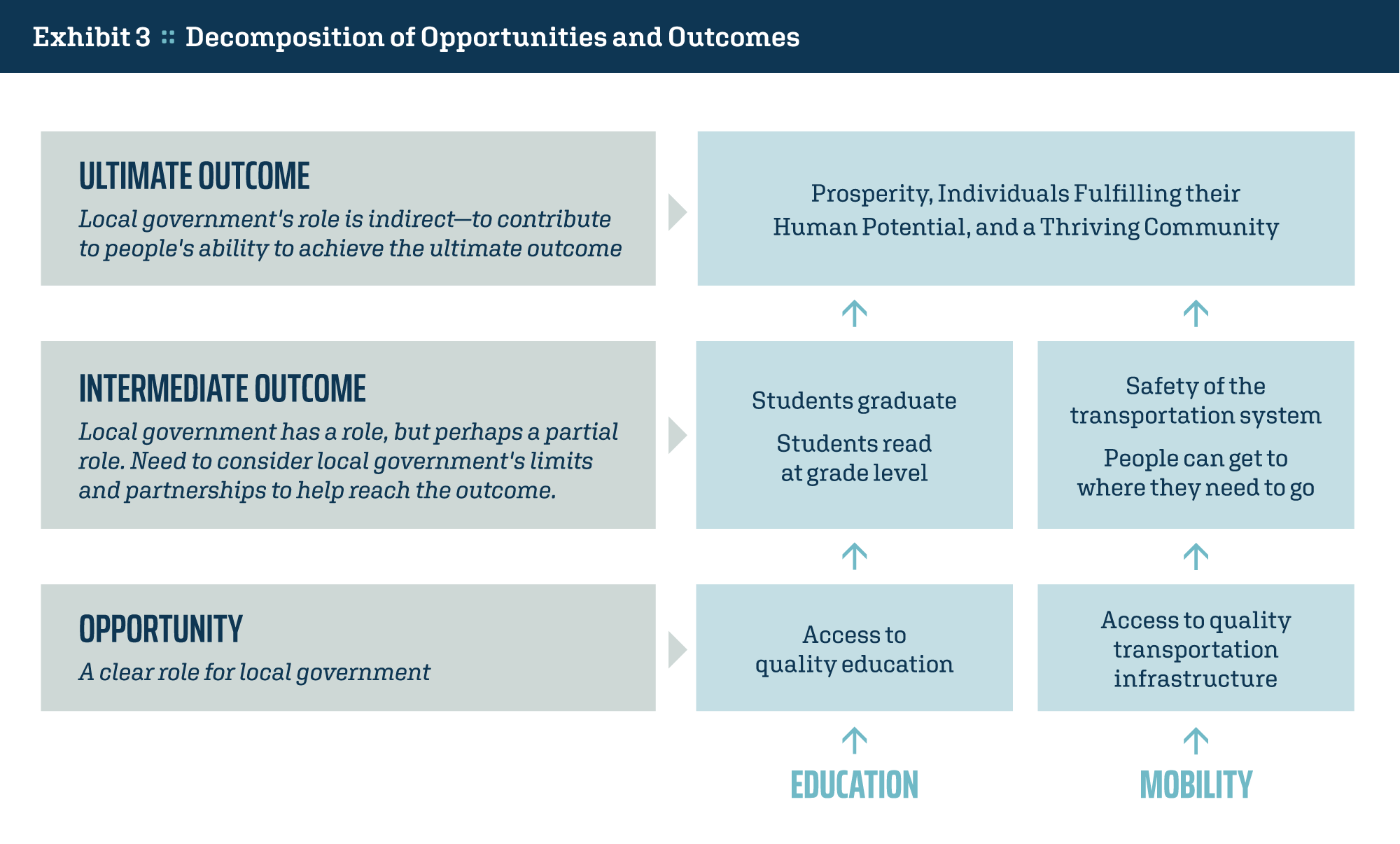

Decompose outcomes. Earlier we described the dichotomy between opportunities and outcomes. This is useful conceptually but may be too simplistic for the real-life issues government faces. It can be helpful to decompose outcomes into ultimate outcomes and intermediate outcomes, and then consider the role for local government. Exhibit 3 illustrates a decomposition for education and mobility, building on the examples we have already explored in this paper.

At the bottom of Exhibit 3, we have opportunities like access to quality education and transportation infrastructure. Providing these services is a traditional role of local government, and a local government can examine its budget to see if these opportunities are provided to all members of the community.

As we move up Exhibit 3, we arrive at intermediate outcomes. Local governments have a role in intermediate outcomes too, but sometimes that role is only partial. Local governments can do a lot to influence all of the intermediate outcomes shown in Exhibit 3. However, there are also things that are outside of a local government’s control. For example, a student’s success in school is a product of many things, not just the efforts of the school system. Local governments can increase the chances of student success by forming partnerships with other organizations that can influence factors that are outside the school’s control. For example, if students come to school distracted by hunger, then they are less likely to succeed in their studies. Some schools have partnered with social service organizations to provide “wrap around” services to get students ready to learn when they arrive at school by addressing food, shelter, clothing, and other basic needs. This is an example of how equity can be put into practice for students from a disadvantaged socio-economic background.

Finally, at the top of Exhibit 3, we have ultimate outcomes. For instance, if students graduate from school ready for college and/or a career, then they are better positioned to achieve prosperity. While success at the intermediate outcomes increases the odds of success in the ultimate outcomes, it does not guarantee it, so the local government’s role is indirect. Whether local government can or even should attempt to play a more direct role is questionable.

So, when local governments consider equity in planning and budgeting, they should differentiate among opportunities, intermediate outcomes, and ultimate outcomes. Planning and budgeting can then focus on where local government has the clearest role, where it may need to form partnerships, and where its role is indirect.

Exhibit 3: Decomposition of Opportunities and Outcomes

Engage citizens in the conversation. Exhibit 2 defined the general role of local government as promoting health, safety, and welfare, but a deeper purpose of local government is to promote democratic engagement. This means that decisions on distribution and redistribution of public resources—and who decides—should be informed by conversations with citizens from across the community. Citizens don’t need to decide specific budget allocations. But if the following conditions exist—public agreement among citizens about values and community priorities, transparency in the decision-making process, and accountability for results—then public trust and confidence in government can be built. Citizens will know their interests are being served and their voices heard, and public officials can be more certain that budget decisions are addressing the highest priorities of all of the constituencies that local government serves.4

Tools for Applying Equity to Budgeting

Deliberations on how to apply equity to budgeting can also be greatly enhanced by conducting a program inventory. A useful program inventory can be developed in a matter of weeks. A program inventory expresses local government activities in units (programs) that are directly relevant to how citizens experience public services. For example, instead of focusing the budget on a department like “public works,” a program inventory identifies a program or service that the department provides, such as removing snow. The city that recognized the importance of removing snow from the sidewalks for the mobility of working-class residents did so with the aid of a program inventory. The program inventory allows a local government to ask: How does a proposed expenditure expand opportunity and access for individuals to the needed government services?

Even if a local government doesn’t have a program inventory, it can still apply the equity principle to budgeting. In today’s environment, many budgeting decisions are about what to cut back. Spending cuts will likely reduce the quality of or access to services that a government delivers. Local governments should consider if a proposed spending cut risks making existing inequities worse. Questions to ask could include:

budgeting. In today’s environment, many budgeting decisions are about what to cut back. Spending cuts will likely reduce the quality of or access to services that a government delivers. Local governments should consider if a proposed spending cut risks making existing inequities worse. Questions to ask could include:

What is the potential for reduced access to services? This includes fewer places to receive service, fewer hours of service delivered, fewer employees to provide a service, longer response times.

What is the potential for reduced quality of service? Cuts will likely lower the quality of service, perhaps to the point where it no longer meets the public’s needs.

Where is the service delivered, and to whom? Services that are delivered to a specific community usually pose the greatest risk to exacerbating inequities, if cut. Examples include schools, recreation centers, libraries, community health centers, or emergency medical service units.

Conclusions

In a time of budget cuts, it is almost inevitable that services will suffer. By taking equity into account, a local government can reduce the pain experienced by disadvantaged parts of the community and reduce the pain experienced by the community as a whole.

(This article was originally published in the Government Finance Review.)

Shayne Kavanagh is senior manager of research for The Government Finance Officers Association.

Jake Kowalski is a public finance consultant at The Government Finance Officers Association.

Notes

1 Katherine Schaeffer, “6 Facts about Economic Inequality in the US,” Pew Research Center, February 7, 2020.

2 Schaeffer, ibid.

3 Kriston McIntosh, “Examining the Black-white wealth gap,” Brookings, February 27, 2020.

4 This section was contributed by Valerie Lemmie, Director of Exploratory Research, Kettering Foundation

(Authors’ Note: The following members of GFOA’s Rethinking Budgeting Project provided invaluable help with the concepts presented in this article: Harpreet Hora, Budget Manager, Roswell, Georgia; Marc Fudge, Interim-Chair, Department of Special Education, California State University San Bernardino; Tammy R. Waymire, Professor, Middle Tennessee State University; Tara Baker, Treasurer, City of Guelph, Ontario; Scott Huizenga, Director OMG, City of San Antonio, Texas; Vicky Carlsen, Finance Director, City of Tukwila, Washington; Stephen M. Wade, Budget and Performance Manager, City of Topeka, Kansas; Krista Morrison, Deputy Director of Business Operations (Parks and Recreation), City of Kansas City, Missouri; Amelia Merchant, Director of Finance, City of Roanoke, Virginia.)