By Rebecca Trout

No two communities are the same, nor do they face the exact same challenges or have the same resources at their disposal. The differences that make communities across the country wonderfully unique and diverse also require solutions that consider variables specific to place.

This uniqueness is perhaps the best case for civic engagement and grassroots problem-solving. When community leaders take the time to engage and involve residents to name problems as they see them and collaboratively develop and implement solutions unique to local stakeholders and resources, outcomes improve, and communities are strengthened. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the communities designated as 2020 All-America Cities. This year’s winners hail from ten different states, each of varying sizes, climates, histories, cultures and political persuasions. All ten applied under the theme of enhancing health and well-being through civic engagement and all ten addressed issues—specific to their communities—with tailored and unique solutions.

Algoma, Wisconsin

Algoma, Wisconsin, a small town on the shores of Lake Michigan, was experiencing a decline in population and employment opportunities. Young people were leaving in search of education and employment and not returning. To stop this trend, the local school district started the Live Algoma Initiative, a local community coalition engaging residents in their personal wellbeing.

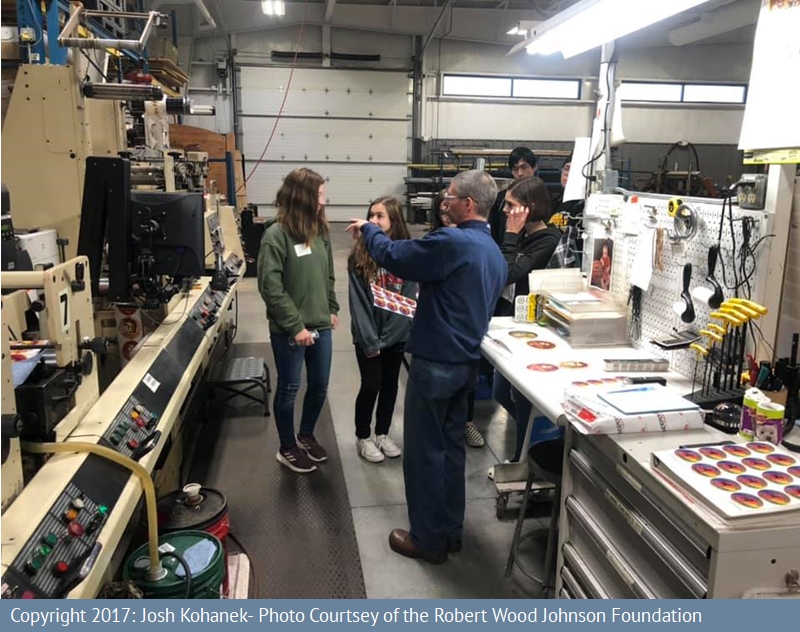

Community conversations indicated that local businesses were calling for better skilled workers and high school graduates needed better education, training and employment opportunities. So, in 2012 Wolf Tech was created with the dual intention of providing manufacturers with skilled labor and offering youth opportunities to explore possibilities for local careers. The program is a series of middle and high school classes that work together with local businesses. Students are given the opportunity to develop practical skills outside of the classroom and businesses get the chance to interact with youth and show them the opportunities in their industry.

Community conversations indicated that local businesses were calling for better skilled workers and high school graduates needed better education, training and employment opportunities. So, in 2012 Wolf Tech was created with the dual intention of providing manufacturers with skilled labor and offering youth opportunities to explore possibilities for local careers. The program is a series of middle and high school classes that work together with local businesses. Students are given the opportunity to develop practical skills outside of the classroom and businesses get the chance to interact with youth and show them the opportunities in their industry.

Students learn and work with professionals in various fields, ask them questions, and potentially obtain a job right out of high school. When certain criteria are met, students can also work before or after school to earn wages. Projects have included building race cars, wood working, welding, blueprint creation, auto maintenance and machinery building.

Students learn and work with professionals in various fields, ask them questions, and potentially obtain a job right out of high school. When certain criteria are met, students can also work before or after school to earn wages. Projects have included building race cars, wood working, welding, blueprint creation, auto maintenance and machinery building.

As a result of addressing the unique challenge of brain drain with existing community stakeholders and resources, local businesses and students alike have benefited. Direct relationships with students have enabled businesses to recruit them for future business endeavors, and youth have been given the opportunity to work with professionals in the community, obtaining education, skills and in some instances, jobs right out of high school.

Danville, Virginia

The health challenges faced in the Dan River region, home of Danville, Virginia, are large and complex. Rates of chronic disease, obesity, poverty, and unemployment are higher than the state and national averages. As a result, The Health Collaborative (THC) was established to take a long-term approach to addressing the community’s health needs. To address health in their community, collaborative members participated in idea-generating activities, reviewed existing data, evidence and case studies, went on site visits to other communities, conducted focus groups, and prioritized strategies. Over 400 individuals shared their ideas and time to create a shared vision and mission to be carried out by several community action teams. One of the action teams launched the Community Health Worker (CHW) initiative to increase the community’s ability to manage chronic diseases.

The health challenges faced in the Dan River region, home of Danville, Virginia, are large and complex. Rates of chronic disease, obesity, poverty, and unemployment are higher than the state and national averages. As a result, The Health Collaborative (THC) was established to take a long-term approach to addressing the community’s health needs. To address health in their community, collaborative members participated in idea-generating activities, reviewed existing data, evidence and case studies, went on site visits to other communities, conducted focus groups, and prioritized strategies. Over 400 individuals shared their ideas and time to create a shared vision and mission to be carried out by several community action teams. One of the action teams launched the Community Health Worker (CHW) initiative to increase the community’s ability to manage chronic diseases.

The primary goal of the CHW project is to decrease avoidable emergency department use. CHWs provide one-on-one care coordination assistance to individuals at risk of being non-compliant with their chronic illnesses. They educate and encourage health and wellness to these individuals by establishing goals during their time in the program.

The workers are community members who are culturally competent and often share ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and life experiences with the members they serve. They reach community residents where they are with home visits over a period of up to 90 days. CHWs focus on medical and social-support service delivery, with the goal of promoting self-management and transitioning the client to a medical home.

The workers are community members who are culturally competent and often share ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and life experiences with the members they serve. They reach community residents where they are with home visits over a period of up to 90 days. CHWs focus on medical and social-support service delivery, with the goal of promoting self-management and transitioning the client to a medical home.

This regionally specific issue, being addressed in a culturally competent and community-specific manner, has resulted in 428 individuals graduating from the program with over 300 connections made to primary care physicians.

Watch Danville’s presentation.

El Paso, Texas

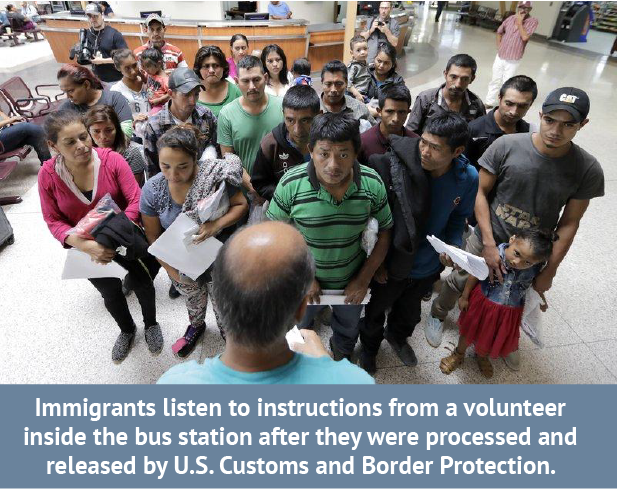

The issue of refugees and asylum seekers made national headlines in 2019, with opinions entrenched largely along partisan lines. But for El Paso, Texas, the issue was more than another sticking point of political partisanship, it was a humanitarian crisis.

In 2019, according to U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, the number of migrants coming from mostly Central America grew by 340 percent, with El Paso experiencing a 1,698 percent increase. It is important to note that a large percentage of the migrants are escaping violence in their own countries, seeking a better life for themselves and their children. Destitute and tired, they reach the border and learn about the thousands more that came before them – waiting, going hungry, and not knowing if their petition for asylum will be heard, much less granted.

In 2019, according to U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, the number of migrants coming from mostly Central America grew by 340 percent, with El Paso experiencing a 1,698 percent increase. It is important to note that a large percentage of the migrants are escaping violence in their own countries, seeking a better life for themselves and their children. Destitute and tired, they reach the border and learn about the thousands more that came before them – waiting, going hungry, and not knowing if their petition for asylum will be heard, much less granted.

El Pasoans came together to volunteer at local shelters operated by various organizations, such as the Catholic Diocese of El Paso and Annunciation House. Residents from all walks of life served as volunteers, taking ground level posts, facilitating food lines, providing clothing and orienting the  participants to showers and beds. Other faith-based and community-based organizations also stepped in to aid in this ongoing crisis. Churches throughout the area held food and clothing drives, identified parishioners for volunteering, and raised funds to help shelters better manage the strain on their capacities.

participants to showers and beds. Other faith-based and community-based organizations also stepped in to aid in this ongoing crisis. Churches throughout the area held food and clothing drives, identified parishioners for volunteering, and raised funds to help shelters better manage the strain on their capacities.

The united approach brought together local community-based agencies, civic leaders, and countless volunteers who donated time, food, medical care, and personal hygiene products to address the immediate needs of the asylees and other migrants.

Franklin, Tennessee

Located in the southern state of Tennessee, the City of Franklin decided it needed to address the legacy of its past as it relates to slavery, the Civil War and segregation.

Since 1899, Franklin’s Public Square has been home to a monument honoring Confederate soldiers who fought in the Civil War. Seeking to avoid racial conflicts such as those in Charlottesville, Virginia, and to be more inclusive of the entire community, Franklin came together to address the divisive issue. Earlier conversations about the monument had drawn criticism from both those wishing to see it remain and those hoping for its removal. In 2018, several local leaders worked closely with the city to develop The Fuller Story, an initiative to deal with Franklin’s past, including the controversial Civil War statue.

Where the statue stands marks the spot where the old courthouse once stood and where African Americans were bought and sold in a slave market. After several conversations with stakeholders, elected officials and residents, a compromise was reached that two African American history markers would be placed on the sidewalk circling the statue. Three additional markers and a U.S. Colored Troops (USCT)* statue will go on the Public Square near the historic courthouse.

The new markers were unveiled as hundreds gathered reverently on the Public Square. The markers represent the Franklin Riot of 1867, U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), Reconstruction, the Courthouse/Market House, and The Battle of Franklin.

In a separate effort, a local battlefield preservation group erected a headstone to honor those who died while enslaved. The stone makes note of those who came to Tennessee from Africa, only to be enslaved until the Civil War’s end.

Watch Franklin’s presentation.

*This was the official name of black soldiers fighting for the Union during the Civil War. The original name is being included for historical accuracy.

Miami Gardens, Florida

Miami Gardens, Florida was incorporated in 2003 out of a quest for self-determination. At the time, escalating crime levels, a dilapidated park system and flat line economic growth were at the heart of residents’ angst; conditions perceived by many to be the effects of a long history of neglect by county officials. Since 2003, significant strides have been made to improve the overall health and well-being of residents.

A grant was used to establish Live Healthy Miami Gardens (LHMG), a concerted, collaborative effort to unite residents, government, nonprofit practitioners, funders, businesses and researchers. Backed by more than 100 stakeholders, LHMG was born from the realization that health is largely influenced by an individual’s choices and the conditions of the community that affect one’s ability to make healthy choices such as access to safe places to play and exercise, good public transportation and housing, and access to high quality and affordable food.

During the 18-months long planning period, a community check-in process was conducted, consisting of focus groups and surveys from more than 700 residents. With the help of over 100 stakeholders, 5 health impact areas were selected, and a community action plan was developed with short and long-term strategies.

Since its inception, this community-driven project has formed Students Working Against Tobacco (SWAT) Clubs; trained residents in cooking classes to promote healthy eating; started a Healthy Restaurant Project; conducted a Mental Wellness Forum to demystify and normalize mental wellness; developed and implemented a Worksite Wellness Program; and launched a “Take Your Loved One to the Doctor” campaign.

Watch Miami Gardens’ presentation.

Muncie Indiana

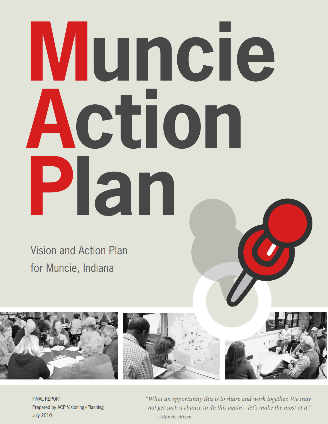

A decade ago, a diverse group of citizens came together to chart a course toward a common future that reflected Muncie Indiana’s shared values and aspirations. Over 2,000 residents and key stakeholders participated in facilitated conversations that resulted in the Muncie Action Plan (MAP) report which created a compelling agenda for the future. The Whitely Neighborhood and Schools Within the Context of Communities project was launched under the MAP umbrella.

A decade ago, a diverse group of citizens came together to chart a course toward a common future that reflected Muncie Indiana’s shared values and aspirations. Over 2,000 residents and key stakeholders participated in facilitated conversations that resulted in the Muncie Action Plan (MAP) report which created a compelling agenda for the future. The Whitely Neighborhood and Schools Within the Context of Communities project was launched under the MAP umbrella.

Faculty members from Ball State’s Teachers College have collaborated with the Whitely Neighborhood and the Whitely Community Council to develop a groundbreaking teacher preparation program called “Schools Within the Context of Community” (SCC). This multi-disciplinary, immersive program prepares socially-just, equity-focused teachers by providing them with unique opportunities to understand the complex contexts in which children are growing and learning.

Pre-service teachers are immersed in the Whitely community to learn from and with community members. The students complete a practicum in the neighborhood’s schools, assist with after school programs, and participate in guided discussions with multiple faculty members and Whitely residents, school administrators, service providers, local pastors, and community elders on issues such as race, language, socioeconomic status, privilege, and power.

Further, each student is “adopted” by a community mentor or mentor family who serves as his/her cultural ambassador. Students and mentors attend family gatherings, worship services, community meetings, and other events together. This provides valuable cultural and contextual insights for working with children and their families both in and out of the classroom.

SCC students also work with Whitely Community Council members to accomplish neighborhood priorities, such as a massive fundraising endeavor to sustain the local community center, grant writing for expanded after-school programs, and the restoration of a historic church in the neighborhood.

This unique approach to teacher development and neighborhood enrichment emphasizes the importance of utilizing community assets and engaging the community to develop collaborative and productive relationships.

Pitt County, North Carolina

Counties often carry the burden of managing the criminal justice system. “Overall, counties invest $70 billion dollars annually on law enforcement, court and legal services and county corrections systems.”1 In addition to the cost, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that 44 percent of prisoners released across 30 states in 2005 were re-arrested during the first year following their release, and 83% were re-arrested at least once during the nine years following their release. To reduce these high rates of recidivism, the Local Reentry Council (LRC) was established to help previously incarcerated individuals navigate through the difficult transition period of reentry. LRC coordinates community resources and addresses service gaps to help recently released inmates become financially independent and productive members of society.

The LRC convened stakeholders and developed innovative strategies and solutions to the problems faced by incarcerated individuals. LIFE of NC—tasked with coordinating all aspects of the reentry process—provides a central location that offers case management, job placement, employment training, legal counsel, substance abuse support, mentoring, transportation assistance, temporary housing, education and vocational rehabilitation through over 45 service providers and employers.

One of those partners is the Third Street Education Center which developed a Business and Workforce Development program that acts as a bridge to gainful employment. Once employed with Third Street through one of their four business areas, participants are provided with assistance in obtaining their GED and National Career Readiness Certification.

In addition to employment, another barrier to reentry is drug addiction. The Sheriff’s Heroin Addiction Recovery Program (SHARP) is a voluntary recovery program that addresses opioid abuse by offering a structured environment where staff provide selected inmates with a strict regimen of classes and activities throughout the day. Pitt County partners with the students from a local stakeholder, East Carolina University, to facilitate a weekly curriculum to develop healthy relationships and life skills, and doctoral psychology students provide weekly psycho-educational sessions with participants.

Since 2015, over 500 individuals have transitioned into the community through the LRC with a 15.9 percent recidivism rate, well below North Carolina’s average recidivism rate of 43 percent.

Watch Pitt County’s presentation.

Portsmouth, Ohio

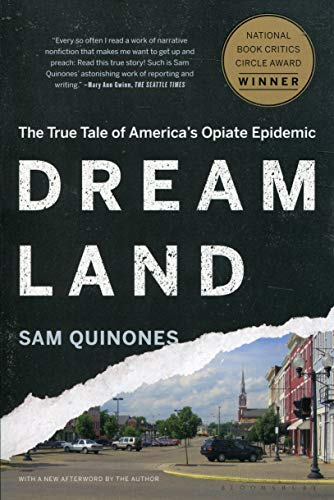

Portsmouth, Ohio was a major manufacturing hub for most of the 20th Century, but changes in both the global and national economy led to deindustrialization and depopulation. This disruption effected economic stability, as well as the larger social order, making it vulnerable to a variety of social problems. Portsmouth was hit hard by the Opioid Epidemic, ultimately being identified as the epicenter, as chronicled in the book Dreamland by Sam Quinones.

Portsmouth, Ohio was a major manufacturing hub for most of the 20th Century, but changes in both the global and national economy led to deindustrialization and depopulation. This disruption effected economic stability, as well as the larger social order, making it vulnerable to a variety of social problems. Portsmouth was hit hard by the Opioid Epidemic, ultimately being identified as the epicenter, as chronicled in the book Dreamland by Sam Quinones.

The first step in dealing with this scourge was to form a coalition of community stakeholders, led by the Portsmouth City Health Department, to provide better treatment and public health resources. The Scioto County Drug Action Team Alliance began to address the drug crisis comprehensively, focusing on prevention, treatment, and drug interdiction.

Interventions, among others, included:

- Educating prescribers on controlled substance prescribing guidelines.

- Conducting community forums to educate the public.

- Implementing youth-led prevention initiatives in 8 school districts.

- Establishing a treatment-friendly Supreme Court Certified Juvenile and Family Drug Court.

- Reversing potentially fatal overdoses through Community-Based Naloxone Education.

- Installing permanent Prescription Drug Drop Boxes throughout the county.

- Securing and condemning drug houses.

- Shutting down illegitimate pain management clinics.

- Providing civil immunity to people who respond to/report an overdose.

- Increasing state-certified addiction treatment centers from 1 to 14 from 2010 to 2019.

- Enhancing access to Medication-Assisted Treatment for opioid use disorders.

Over time, these efforts have led to significant reductions in youth substance use and improved health outcomes in the population; however, more work was needed to repair Portsmouth’s spirit and sense of community pride.

After years of negative media attention and community trauma brought on by the opioid epidemic, Portsmouth needed to boost the morale of residents.

Portsmouth took a creative approach to improving community pride by hosting several events designed to break Guinness World Records. Plant Portsmouth broke the Guinness World Record for the most people potting plants simultaneously and residents attending Winterfest, broke the world records for the most people Christmas caroling and wrapping presents simultaneously.

In addition to community-building events, historical spaces that were previously assigned negative connotations as symbols of decline are now being transformed into symbols of Portsmouth’s resurgence. McKinley Pool, significant to Ohio’s civil rights movement, received its most substantial funding, allowing for improvements to pool facilities. Additionally, the Spartan Municipal Stadium, a stadium that was once home to the former National Football League team, the Portsmouth Spartans, was made safer and more secure.

Watch Portsmouth’s presentation.

Rancho Cucamonga, California

In Rancho Cucamonga, California’s first General Plan, the community stated its aspiration to conserve land with a series of rural neighborhoods and open spaces located in the foothills, just outside the city limits. Over the course of three decades, several unsuccessful attempts were made to annex this land which was being used as a gravel mine that had begun to scar the natural landscape.

Once the gravel mine finally closed, the city partnered with the county to annex the land and develop a plan to transform the mining site into a series of healthy, walkable neighborhoods and thousands of acres of conservation.

Once the gravel mine finally closed, the city partnered with the county to annex the land and develop a plan to transform the mining site into a series of healthy, walkable neighborhoods and thousands of acres of conservation.

To the city’s surprise, once presented the plan, the community expressed disappointment with the lack of inclusion and felt the city was forcing new development upon them.

The city set aside the preliminary concepts and began engaging the community in the creation of a new plan. City staff began by bringing blank maps to community workshops, representing a clean slate. Together, citizens and staff shared the responsibility of crafting a strategy to develop the quarry into desired neighborhoods while preserving the natural elements of the foothills.

The city embarked on further engagement, in both English and Spanish. Nine pop-up outreach events engaged over 800 community members. Virtual workshops, surveys, and other digital engagement events were held to ensure that all residents were able to receive information, ask questions, and provide feedback.

The city embarked on further engagement, in both English and Spanish. Nine pop-up outreach events engaged over 800 community members. Virtual workshops, surveys, and other digital engagement events were held to ensure that all residents were able to receive information, ask questions, and provide feedback.

The resulting Etiwanda Heights Neighborhood and Conservation Plan articulates a shared vision for extensive conservation of the foothills and alluvial fans, as well as walkable neighborhoods that reflect the rural history of Etiwanda.

Watch Rancho Cucamonga’s presentation.

Rochester, New York

Rochester City School District (RCSD) data showed that Black students were suspended 2.5 times as often as their White peers, and students with disabilities were suspended twice as often as their general education peers. Given the troubling research linking out-of-school suspensions to eventual incarceration, Rochester activists and community members invited the Advancement Project to help bolster local capacity to address the school-to-prison pipeline.

The Advancement Project helped launch a collaborative effort facilitated by the Rochester Area Community Foundation, along with a wide variety of community stakeholders. The Community Task Force on School Climate (CTF) was formed to develop recommendations to improve school climate in the district.

After a lengthy revision process that involved input from hundreds of students, parents, educators and community members, the RCSD Board of Education unanimously passed a new code of conduct, detailing RCSD discipline policies. The new code removed criminal language, clarified vague guidelines, made suspensions a last resort and promoted alternatives to suspension such as restorative practices.

In the new code’s first year alone, total suspensions dropped a remarkable 27% and a further 8.4% the following year. Additionally, RCSD adopted several other interventions, including professional development in restorative practices and help zones replacing in-school suspension rooms.

Watch Rochester’s presentation.

Rochester has more recently been in the news when details of the death of Daniel Prude came to light. Prude, who suffered from mental illness, died of asphyxiation in March after being cuffed, hooded and held face-down on the pavement by police officers answering a 911 call. His death has led to protests and community discussions on race and policing in Rochester.

The All-America City Awards do not honor perfection because there is no perfect community. Each of this year’s winning communities face unique challenges, from immigration, obesity, drug addiction and historical inequities. What is recognized and celebrated in each of these communities, however, is their courage to admit to and make a commitment to facing these challenges in a way that is inclusive of residents, businesses, non-profits, government officials, and additional stakeholders alike. While cookie-cutter solutions would be convenient, they are simply not practical in communities with such different needs, challenges and resources. When residents come together to put their various perspectives, skills and resources to use, even the most intractable of problems seem less daunting.

Rebecca Trout is Program Director for the All-America City Awards and Communications at the National Civic League.

1 NACo analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, 2007 Census of Governments, Government Finance. (Department of Commerce, 2007). Expenditures of county-city consolidations and independent cities that are considered county governments under state law are included in the total for counties.