By Zachary Clifton and Charles Yale

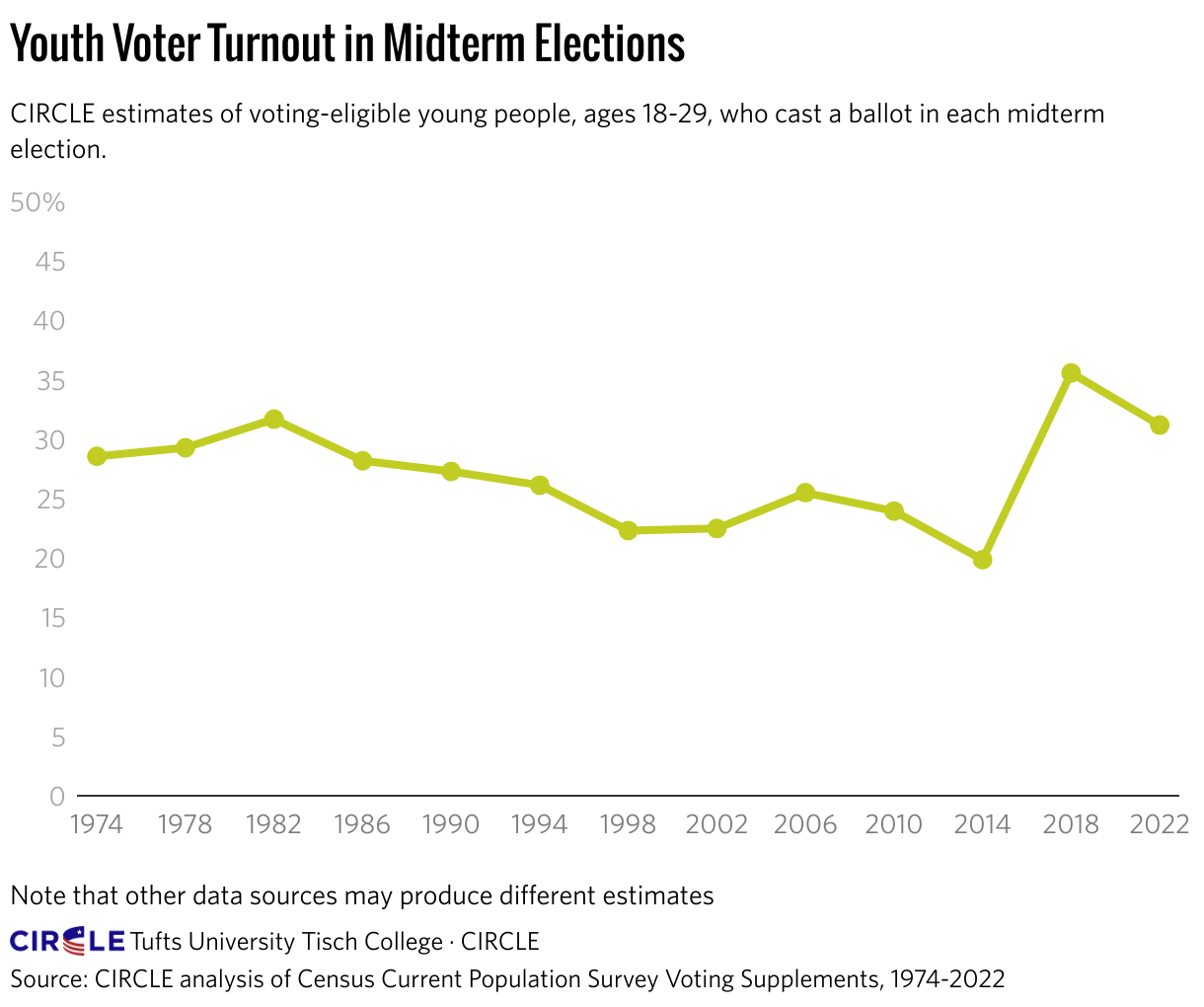

In 2020, at the culmination of a hard-fought presidential campaign and a fiercely contested general election, the United States saw rates of voter participation and civic engagement amongst young people soar to a 50-year-high. Notably, the U.S. hadn’t seen young people vote at a rate as high since the voting age was lowered from 21-years-old to 18-years-old in 1971, according to the Tufts University Center for Information and Research on Civic Engagement (CIRCLE).

Despite this encouraging improvement, the youth turnout rate was still the lowest out of all age groups, according to the Rutgers University Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP). While the U.S. made a historic reform to youth voting with the passage of the 26th amendment, today, in 2023, the New York Times reports that young people don’t outvote their elders in any country in the world—a statistic that could be upended by America’s youngest generation if the U.S. Congress made another vicennial effort to systemic improvement in youth voting.

Low participation rates for the youngest American voters are certainly no accident. They are the result of conscious choices on the part of policymakers.

The majority of voter-suppression bills introduced since 2020 aim to make it harder for young people to vote. But the impact of suppressing the youth vote is twofold: younger Americans are also the most racially diverse age group, meaning that the intentional suppression of young people is also the intentional suppression of a cohort that is more racially diverse than ever before, a fact that magnifies the impact of keeping young people out of the civic and electoral process. Young Americans are also the cohort that will have to live for the longest with the decisions that the government makes today.

Throughout U.S. history, young people have faced systematic exclusion from the political process. To tackle this issue, we need to confront the reality that young people are not uninterested, but disenfranchised, and start acknowledging how past and present government policy negatively affects their participation in elections. Without confronting this reality, we can’t truthfully reevaluate electoral policy in the U.S.

Disenfranchised, not Disengaged

A common interpretation of low youth turnout rates in elections is that young people are less interested in the political process at large than other groups of voters. But, statistics have repeatedly shown that this is simply not true. The 2023 Harvard Kennedy School’s annual Youth Poll showed that more young people than ever before are interested in engaging in politics. But youth turnout is still the lowest of any age group in the U.S. This is because of barriers that state and federal governments have put in place that, according to Charlotte Hill, doctoral candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, date back to post-Reconstruction Jim Crow laws. “I think of the U.S. as an anomaly when it comes to disparities in turnout across groups, and that those disparities are inseparable from a legacy of slavery and racism,” Hill said.

Take, for example, the opportunity cost when it comes to voting. Disenfranchised groups, such as young people and people of color, often have stricter or more unpredictable work schedules than older white Americans. Federal elections, which fall on Tuesdays, are in the middle of the work week. As a result of their schedules, young people may have less of a financial cushion or ability to take time off to vote.

Even seemingly small things — such as the ability to take off work to vote in an election — often have disproportionate ramifications for young people. In addition to employed youth, however, college-attending young people in many states have faced even more systemic barriers, including in Ohio where the legislators recently passed legislation to limit accepted IDs for voting.

Even once young people are at the polls, though, they still cannot rely on their vote being counted. Policies influencing the acceptance and rejection of mail-in ballots have the same effect of diluting youth voice. A study of rejected mail-in ballots after the 2018 Florida midterms found that young people’s ballots were rejected at a rate around 9 times as often as those being sent by people 65 and over — 5.39 percent to 0.63 percent, respectively. The total number of ballots rejected, which the study puts at 31,969, could have drastically changed the results of two statewide elections; this includes the race for Senate, which was won by 10,033 votes, and the gubernatorial race, decided by 32,463 votes.

Unfortunately, this pattern is consistent across multiple states. A study found that during the 2018 midterms in Georgia, vote-by-mail ballots from the age group of 18-22 were more likely to be rejected than any other age group. And, in Colorado, young people represented the bulk of the nearly 29,000 ballots rejected during the 2020 presidential election. The evidence overwhelmingly shows that there is something fundamentally wrong in the way that the government either teaches or adjudicates voting for young populations.

In 2023 alone, the Brennan Center for Justice reported that at least 11 states have passed 13 laws restricting voting access. All of these pieces of legislation look to silence the voices of young people.

Disproportionately Low Representation, Disproportionately Large Effects

Three million children in the United States were lifted out of the grips of poverty during 2020 and 2021. However, by the end of 2022, after the end of expansive economic policy to directly provide millions of Americans with transfer payments, the U.S. ended its pandemic-era Child Tax Credit.

While researchers at Columbia University concluded that if the Child Tax Credit had remained in place, poverty would have continued to decline — by as much as 50 percent — amongst children in 2022, this stark incentive did not materialize to a policy change or anticipatory action from the U.S. Congress.

In fact, despite inaction on continuing the U.S.’s progress on reducing poverty among children, Congress approved a budget last year that, according to the Brookings Institution, allocated nearly two-thirds of spending to entitlement programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and Unemployment. However, starting in 2033, programs like Social Security may not be able to fully pay out to the younger groups most affected by the current situation.

According to figures from the Wharton School of Business, in 2022, Universal Pre-K for 3-year-olds and 4-year-olds would cost approximately $351 billion over the next ten years — however, if we allocated a single year of federal spending for entitlement programs toward Universal Pre-K, it would be funded beyond the next 100 years.

Obviously, the average elected official in our country is much older than the average preschooler — in fact, the average U.S. congressperson is nearly 20 years older than the average U.S. citizen. As of February 2023, there were more people in the U.S. House of Representatives over the age of 78 than under the age of 38 — approximately the age of the average person in the United States.

Why do the ages of our elected officials matter? Because last year child poverty had its single-highest increase in a single year, and for fiscal year 2023, monthly Social Security payments increased by 8.7 percent.

According to Scott Galloway, N.Y.U. Stern School of Business Professor of Marketing, this phenomenon can be described as our country having “purposefully, through our legislative policies…decided to implement a series of policies that transfer wealth from young people to old people.”

Simply stated, Galloway is aware of the ongoing crisis of an ever-aging electorate governing in a way that increases Social Security and Medicare payments to the elderly, while upending funding to vital programs that benefit young people.

In order to systematically dismantle the continued perpetuation of our American Gerontocracy, radical reforms must be put into place.

Not only are older congresspeople exacerbating an ongoing Social Security crisis, but they are becoming increasingly out-of-step with the rest of the American population. A Gallup Poll from this year pointed out that while most young people prefer the label of “pro-choice,” a majority of Americans 50+ identify with the term “pro-life.” The upheaval and overturn of Roe v. Wade by a Supreme Court that has a median age of 63. But it isn’t only social issues that older Americans disagree with younger Americans on.

Following bipartisan calls to restrict the social media application TikTok, Republicans decided to call Shou Zi Chew, TikTok’s CEO, for a hearing. Out of the gate, Frank Pallone (D-NJ), who is 72, referred to the internet as the “information superhighway,” a phrase that has been out of use since the late 20th century. Richard Hudson (R-NC) asked whether TikTok was able to access the home Wi-Fi network (shocker — it is). And the 66-year-old Buddy Carter (R-GA) asked whether or not TikTok tracked eye dilation data, to which Mr. Chew responded “the only face data that we collect is when you use the filters to have sunglasses on your face.”

The only thing that is as stark as the spectacle of a U.S. Congress that is too old to legislate on behalf of their youngest constituents, is a U.S. Congress that refuses to understand the fastest growing social media site in the United States, TikTok.

How do we Involve Young People in the Civic Process?

The involvement of young people in the civic process starts with making voting easier.

At least 36 states have voter identification laws, and 12 of those states don’t allow student IDs as valid forms of ID. The simplest way to fix this is federal regulation of voter ID. The Government Accountability Office explained that there is a negative correlation between voter ID laws and voter turnout, meaning that the stricter voter ID laws tend, the less people vote. It’s also imperative that it become easier for young people to vote on federal Election Days — that means turning Election Day into a national holiday or making it easier for people to take time off to vote. What this doesn’t solve, though, is the fact that registering to vote may be a barrier for young people in the first place.

A radical, inclusive advancement would be to eliminate the step of registration in the first place: automatic voter registration (AVR) would ensure all Americans were registered to vote as soon as they turned 18 and interacted with a government agency, like the Department of Motor Vehicles. Instead of voter registration being an opt-in program, like organ donation, it would be one that Americans would have to opt out of if they didn’t want to participate. Preliminary research from Oregon in 2016 showed that AVR increased registration by more than 272,000 voters, and more than 98,000 of them were first time voters. 116,000 people registered who were previously unlikely to have done so otherwise, and more than 40,000 of this population voted in the 2016 presidential election. The brunt of AVR registered voters were noticeably younger than the voter population at large — about 40 percent of AVR registrants and 37 percent of AVR voters were age 30 or younger. In comparison, 20 percent of eligible Oregon citizens are aged 18 to 29. A study from the USC Price School of Public Policy showed that AVR helped to decrease the voter registration gap between younger and older voters in more recent elections, but only in certain states. CIRCLE’s analysis of 2020 AVR programs showed that they increased youth registration by 3.5 percentage points as compared to non-AVR states.

But there are mainstream solutions with greater public buy-in that are plenty sufficient to correct our country’s disenfranchisement of young voters. In fact, short of AVR, we can turn to facilitative election laws — by definition, laws that make voting easier. Twenty-two states as well as Washington D.C. have implemented same-day voter registration (SDVR). Of these states, 20 allow SDVR on Election Day. North Carolina and Montana both allow SDVR during the early-voting period, but not on election day.

Policies like SDVR help to reduce barriers to voting for every group in the U.S., but particularly marginalized populations: in 2020, Black and Latino turnout was between 2 percent and 17 percent higher in states with SDVR as compared to states without it. SDVR also eliminates arbitrary cutoff dates in the last 25 to 30 days before an election, when Americans often become most involved in politics. Much of the opposition to SDVR stems from the fact that people see it as a route to more fraud. But, election officials explained in consecutive Demos polls that “current fraud-prevention measures suffice to ensure the integrity of elections,” and SDVR would not impact fraud in any significant way. SDVR would also enable geographically mobile voters to update their information at their polling place, instead of preemptively registering to vote.

The exact specifications and impact of altering entitlement programs are not certain. What is certain is that a continuation of the American Gerontocracy would be harmful to the interests of our country’s youngest generation. A national conversation on ways to increase voter participation and civic engagement amongst young people is a necessity in order to generationally shift power and increase equity for the youngest, most vulnerable American citizens.

Zachary Clifton is an advisor for the National Civic League, a board member of the Kentucky Student Voice Team, and an 18-year-old student from Corbin, Kentucky.

Charles Yale is a 17-year-old activist and student journalist from Omaha, Nebraska.