“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” the preamble of the Declaration of Independence asserts.

As the Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) Design Team acknowledges, “Unfortunately, the ‘certain unalienable Rights’ and ‘Liberty’ was not meant for those whose basic humanity had long been denied by the founders. They were not meant for Native Americans, whose property was stolen, whose people were massacred, and whose culture was repressed long before independence from England was contemplated. Nor were they meant for African Americans, whose labor was stolen and whose freedom was denied from the earliest days of the colonies. Nor were they meant for various immigrant populations who were deemed unworthy of enjoying basic human rights unless they shed their culture and ‘melted into’ the dominant culture.”

The false belief in racial and ethnic hierarchy has been infused throughout the U.S. legal system and operates in both blatant and insidious ways through laws, public policies, and accompanying practices and norms. Whether deliberately or unintentionally, laws and policies have enabled, sustained, and exacerbated unequal treatment of people of color. These historical contexts underscore the need to reimagine the design of the entire legal system into a framework that is intentionally structured to center respect for communities of color. We acknowledge there is a broad spectrum of approaches to reimagine policing and there are various movements with a myriad of viewpoints. As a best practice, any strategy that is implemented across the spectrum should be informed by the needs and voices of the local community, particularly marginalized populations.

For example, U.S. policing was historically deployed for the social control of communities deemed socially marginal — it evolved from ruling-class efforts to control the immigrant working class in the North and from slave patrols in the South. Policies and practices continue to implement and sustain this historical intent. For example, the war on drugs assigned drug use intervention to law enforcement in lieu of formulating a public health approach. Scholars suggest that the associated “tough on crime” rhetoric was a racially coded appeal to white populations across class lines aimed at legitimating targeted policing in communities of color. Enforcing policing largely remains an unequally occurring mechanism of social control resulting in over-policing of communities of color, especially Black communities. The criminalization of houselessness, sex work, and drug abuse exemplifies how law enforcement is deployed to rectify social inequities.

Fortunately, in the same way that laws create and perpetuate inequities, they can also be used to spur positive and transformative change.

The following are measures to transform the legal system into one that “honors the dignity of all people, upholds the civil and human rights of all, and encourages full civic participation from all communities,” as the TRHT designers envisioned:

- Endorsement and implementation of 21st Century Policing recommendations and other comprehensive police reforms.

- Diversion of police funding to support alternatives to policing and prevention programs.

- Reclassification of violations, decriminalization, and bail, probation, and fees reform to address racial and socioeconomic biases.

- Immigrant-friendly policies and practices to promote equitable opportunity.

- Voting rights protection and expansion.

Endorsement and Implementation of 21st Century Policing Recommendations and Other Comprehensive Police Reforms

According to the Mapping Police Violence database, there were over 1,100 deaths by police action in 2020.1 This database has documented 7,645 total deaths between 2013 and 2020, and over 120,000 reports of police misconduct.2 Further, in 2019, there were over 86,000 (reported) nonfatal injuries due to legal intervention.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the overall cost of fatal and nonfatal injuries by law enforcement reported in 2010, including medical costs and work lost, was $1.8 billion.4 Legal scholars describe a clear connection between increased exposure to stops by police and an elevated risk of death or physical harm by law enforcement officers.

People of color, who represent just under 40% of the U.S. population, accounted for more than 50% of years of life lost due to legal intervention in 2016.5 Native Americans have been killed by law enforcement at a higher per capita rate than any other group in the United States (3.5 times higher than white Americans), with these mortality data likely to be an undercount.6 Stratification by gender and age showed that Black and Native American males 15 to 34 years of age were nine and six times (respectively) more likely to be killed than other Americans in their age group.7 Similarly, Black women are disproportionately represented among women killed by police.8 Black and Latino individuals are more likely to be stopped and arrested and to experience nonfatal violence by law enforcement.9 10 11 12 Further, students most at risk for violence by school-based law enforcement officers include children with disabilities, students of color, and poor students.13

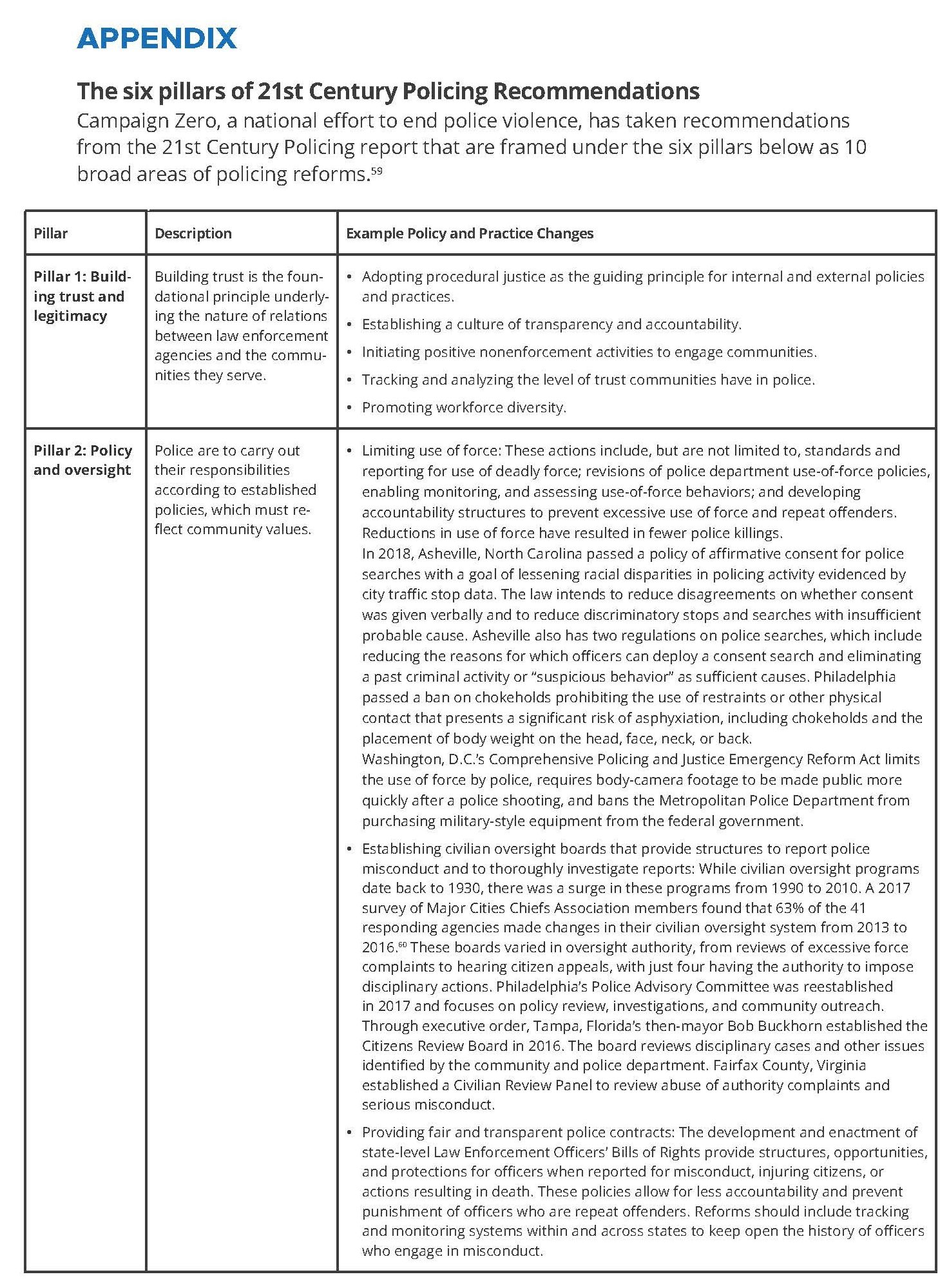

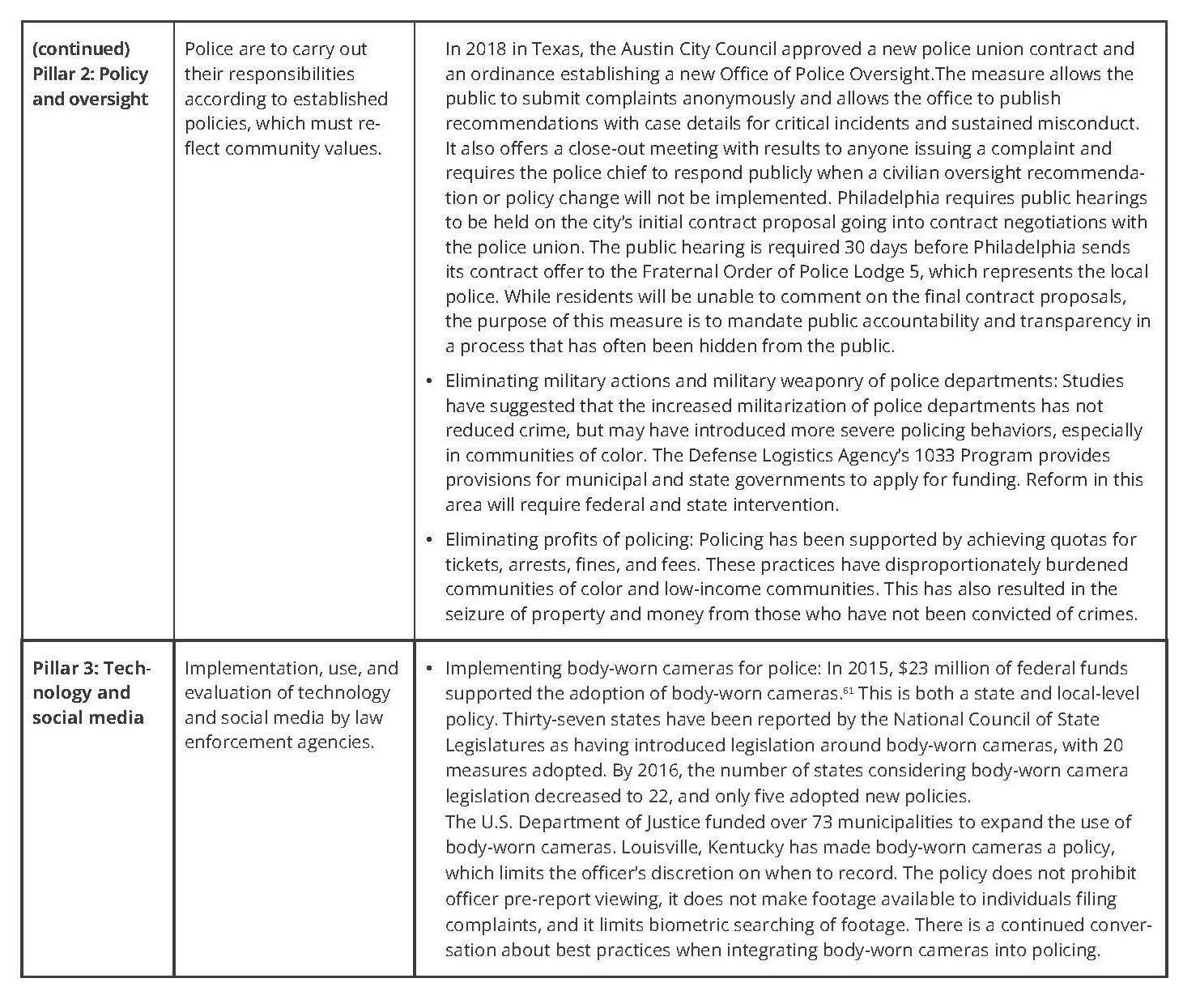

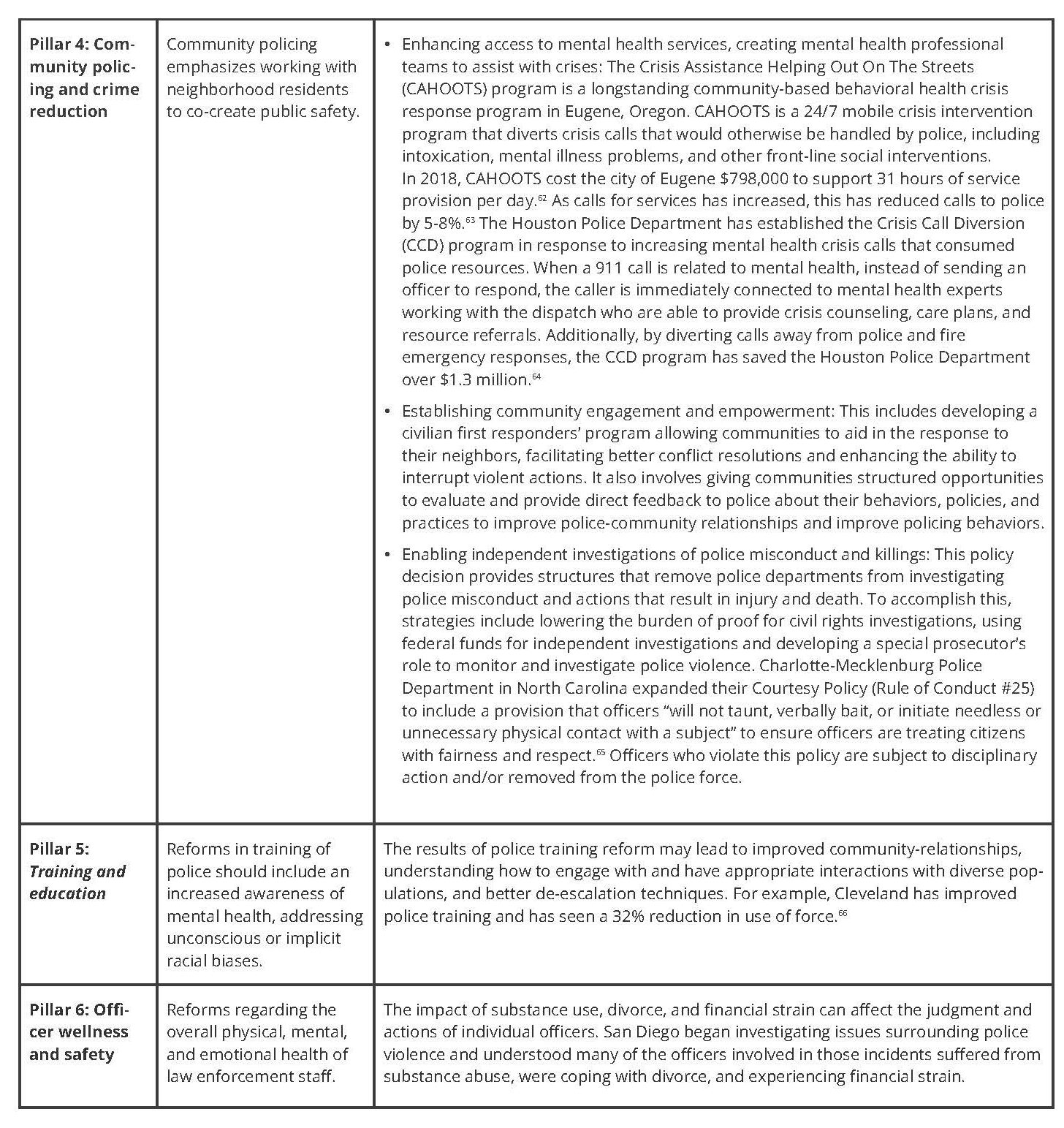

Addressing structural racism in police reform is not new. However, the study of its potential impact on health inequities has gained momentum within the last decade. The range of police reforms that have been enacted are best summarized in the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing report, which was developed during the Obama administration and includes over 50 recommendations and 92 action steps. The more recent editions of the report focus less on specific recommendations and more on six pillars of police reform:

- Pillar 1: Building Trust and Legitimacy

- Pillar 2: Policy and Oversight

- Pillar 3: Technology and Social Media

- Pillar 4: Community Policing and Crime Reduction

- Pillar 5: Training and Education

- Pillar 6: Officer Wellness and Safety

A more detailed description of each pillar along with discussion of 10 broad areas of policing reforms can be found in the Appendix.

The U.S. Conference of Mayors has reports on implementation best practices of 16 cities that have adopted 21st Century Policing reforms (or beyond), including Aurora, Colorado; Baltimore; Boston; Charleston, South Carolina; Phoenix; Sumter, South Carolina; and Schenectady, New York. Further, there are many states and municipalities that are considering have passed a policing reform. An example of the potential coverage of some reforms includes a report from the U.S. Department of Justice, which has funded over 60 municipalities for body-worn cameras as an example of local-level police reform, according to the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Evidence of Improving Health and Racial Equity

The combination of police reform and anti-racism policy declarations can lead to change in government structures, increase community engagement, and reduce negative health outcomes in communities that are hyper-surveilled and lethally policed. This ultimately leads to greater health and racial equity nationwide.

The six pillars of police reform provide a pathway to improve police- community relationships, and enhance transparency and accountability — which includes improving the accuracy of data about policing behaviors, disciplinary actions, and demographics of police agencies. Data about police agencies is limited, and gathering this information does not reduce the disproportionate burden of police violence within communities of color. The communities that are subjected to lethal policing and hyper-surveillance are low-resourced and composed of racial and ethnic minority groups with high rates of chronic illness.

Feasibility

Police reform is happening. At times it may appear to move at a slow pace or become stalled within political debates about the range of options and what communities, local city councils, and state legislators believe reduces police violence but maintains the role of police in upholding community safety. An equitable approach includes ensuring community voices are centered and a part of every stage of reform. This also includes evaluation and assessment used to inform how citations are issued and contributing to the analysis of the broader community impact of those reforms on community health and well-being and police-community relationships.

One major unsolved challenge is accurate data collection about police behaviors. For example, the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics survey includes data from only about 3,000 state and local law enforcement agencies.14 There is no federal mandate for reporting of police agency-level data, and police unions often prevent against collecting this information. As of this writing, no presidential executive orders have mandated such data collection.

Diversion and/or Reallocation of Police Funding to Support Alternatives to Policing and Prevention Programs, such as Investments in Behavioral and Mental Health Services

Although many cities allocate large percentages of their general funds to policing, this spending often doesn’t correspond to the actual rates of violent crime in those cities. Since the 1990s, police spending in the United States has remained constant, even though violent and property crime have dramatically declined.

This demonstrates that although police department budgets are among the largest line items in many locality budgets, increased policing does not help the public’s health and well-being. Police spend most of their time responding to minor incidents, and the majority of arrests (80%) are for low-level, non-violent offenses such as “drug abuse violations” and disorderly conduct, according to the Vera Institute of Justice.15 In 2015, police violence caused more deaths than diabetes, flu/ pneumonia, chronic respiratory disease, or cerebrovascular disease among Black men in their twenties.16 These killings also contribute to worse mental health effects among other Black Americans in the community, and in other states when there is media coverage of these killings. Additionally, studies have shown that police contact is a predictor for increased delinquent behavior among Black and Latino adolescent boys, and police stops are associated with harmful outcomes for young boys. Over-enforcement of minor incidents reduces community trust in law enforcement, making police less effective, and can lead to increases in violence.

Community alliances among local county health services, law enforcement, mental health services, and community members are designed to address the needs of community members experiencing a mental health crisis. In 2019, police departments with a crisis intervention team program represented only around 15-17% of the total number of police agencies nationally.17 A 2015 survey by the Police Executive Research Forum found that that while new recruits received a median of 58 hours on firearms training, only eight hours were spent on crisis intervention or de-escalation training.18 In addition to improving safety, health, and equity, resources may be more efficiently and effectively used if mental health professionals and social service personnel are those deployed to calls for non-violent, non-criminal situations, rather than having armed police officers be first responders to mental health or other crises. Diverting funds from police departments allows for more qualified professionals to respond as appropriate and supports programs and efforts that improve health. Additionally, research has found that prioritizing and investing in education, health care, and community-led public safety measures not only improves public health, but also reduces crime.

There is an increasing demand among communities to reallocate or redirect funds from the police department to support alternatives to policing, including education, social, and prevention programs. Cuts to local police department budgets can pay for programs that have been underfunded at the expense of increasing police budgets, such as education, health care, and social services. Reallocating funds from policing to other programs involved in social determinants of health has the potential benefit of reducing conflict and police violence while simultaneously improving community safety and health. Alternatives to policing will depend on police departments partnering with community-based services and programs that focus on addressing root causes of crime and social determinants of health, such as mental illness, housing, education, and poverty. To promote alternatives to enforcement that do not involve the criminal justice system, these community-based services require investment and support from localities. Without such services, police officers will continue to default to current response practices out of necessity. With more communities calling for policing reform, local municipalities can reflect citizen priorities in their budgets by using the funds saved from reducing the size or scope of police departments to invest in services and programs better suited to responding to community needs.

Policy Examples

In 2020 budget votes, campaigns to reallocate funds to meet community needs resulted in over $840 million in direct cuts from local U.S. police departments, at least $160 million in investments to communities, and the removal of law enforcement from schools in 25 cities.19 Several cities have recently approved plans to cut or divert police department budgets to fund equity and inclusion programs and invest in alternative response personnel or services. Creating units and programs such as mobile crisis assistance teams, mental health support teams, and call diversion programs are examples of how local governments can play a key role in shaping new outcomes for policing.

In San Francisco, $120 million was redirected from law enforcement to investments in economic opportunity, youth development, housing and homeownership, and health and well-being in Black neighborhoods.20 Boston reallocated 20% of the police overtime budget ($12 million) to investments in equity and inclusion, including efforts of the Boston Public Health Commission.21 Salt Lake City reduced its police department budget by $5.3 million, reallocating $2.5 million to fund a social worker program and $2.8 million to be reserved for other uses, informed by the newly formed Commission on Racial Equity in Policing.22 Albuquerque, New Mexico, established a Community Safety Department to act as a third public safety department, in addition to the police and fire departments.23 The department dispatches first responders to respond to non-violent 911 calls involving inebriation, homelessness, addiction, and mental health.24 Austin, Texas cut $21 million from the police budget and reinvested the money into the COVID-19 response; services for unhoused people; addressing substance use, mental health, and family violence prevention; and other forms of public safety and community programs.25

In June 2020, the Baltimore City Council approved a $22 million cut from the police department’s budget.26 The same month, Hartford, Connecticut cut their police department funding by $1 million to go toward community serving agencies, including public works, children, youth and recreation, and health and human services.27 Norman, Oklahoma’s city council cut its police budget by 3.6%, or $865,000, and reallocated spending on community development programs and the creation of an internal position to track police overtime and outlays.28

Promise for Improving Health and Racial Equity

The cycle of policing produces conditions that become causes of crime, which results in increased policing. Documented poor health outcomes linked to policing include fatal injuries, adverse physiological responses, and psychological stress. Research has also found significant mental health implications among Black Americans, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and trauma from the threat of violence and murder at the hands of police, in addition to direct experience with police mistreatment or abuse. Additionally, similar mental health implications have been found in those who have not directly experienced police violence, but are in the same communities, resulting in collective trauma in Black neighborhoods and Black communities. Investments in community-based drug and mental health treatment, education, and other social institutions, rather than into police departments, can make communities safer while improving life outcomes for all. Reforming policing and utilizing alternatives to armed police as first responders to mental health and other forms of crisis would also likely reduce the rate of death due to police violence.

Feasibility

A potential challenge of decreasing police department budgets is ensuring that the recruitment of younger and more diverse new hires as well as new trainings intended to reform enforcement are not cut from the budget. When police departments face budget cuts, certain measures that even advocates of police reform propose, such as community relations programs and recruitment efforts for younger and more diverse officers, are typically the first items cut from the budget.

Additionally, even if the police department is the one making the investment into a crisis intervention team, they may not be the department that accrues the savings, making it difficult to gain support from these departments from a cost savings perspective. A police department or department of health may incur the costs of training and personnel, but other departments or other levels of government will see the savings, making it more difficult for budget managers in a police department to justify spending on alternative, non-police first responder staff when competing with other departments for funds.

However, there is broad support for reform among law enforcement practitioners, who have voiced frustration with having to play too many roles in their communities and being expected to act as the default party to respond to complex social problems such as homelessness, substance use, and mental health crises. A July 2020 national poll from Gallup found that overall, 47% of respondents supported reducing police department budgets and shifting the money to social programs, although there are large gaps by political party.29 Another national poll that framed defunding more generally asked about redirecting taxpayer funds to other agencies so that they could respond to certain emergencies instead of police. It found that overall, most supported redirecting money from police departments and reallocating funds to pay for other service providers to respond to calls about medical emergencies, addiction, mental illness, and homelessness. Specifically, 72% supported redirecting money from police departments to pay for mental health experts, with 67% of white respondents and 87% of Black respondents supporting these changes.30 Overall, 66% supported reallocating funds to pay for social workers to respond to calls involving a person experiencing homelessness, with 64% of white respondents and 71% of Black respondents.31

Reclassification of Violations, Decriminalization, Bail, Probation, and Fees Reform to Address Racial and Socioeconomic Biases

State and local government use of criminal fees and fines to fill budget gaps was reintroduced in the 1980s. The use of these fines as a revenue strategy accelerated in 2008 during the economic recession, despite declining rates of crime in the United States since the 1990s. Violent crime rates fell 51% between 1993 and 2018, while the property crime rate decreased 54% during the same time frame.32

Policing in these communities is part of a general form of hyper-surveillance that may be linked to the resurrection of defacto debtors’ prisons to close deficits in many counties and municipalities. Municipalities have relied on police officers to collect fines and fees from criminal convictions, traffic fines, and child support payments and engage in disproportionate vehicle stops. These offenses thereby entrap poor (largely) Black communities in a cycle of imprisonment and poverty and have contributed to declining revenues since the 2008 recession. Currently, an estimated $50 billion of carceral debt is being held by 10 million people.33 The COVID-19 pandemic also increased calls for the reduction or suspension of fines and fees because of job losses, disruptions in employment stability and income flow, and many feeling they would not fully recover from the pandemic. Research on fines and fees in Indiana prove that one implication of unpaid fines may be converted into a civil judgment, which can be used to obtain real estate liens. This action was challenged in Timbs v. Indiana, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that local governments should be banned for collecting excessive fines such as the seizure of property to pay for fines individuals cannot afford.

The cost of managing probation, or community supervision programs, has become more unwieldly over the past decades. Historically, these efforts were developed to be less punitive and provide restoration for those recently incarcerated. Over time, the parole and probation process has become costly to individuals released from imprisonment and their families, and has created administrative challenges to managing caseloads, increasing costs to taxpayers, and becoming a primary driver for incarceration.

Policy Examples

There is a growing list of court activity produced by the Fines and Fees Justice Center to reduce or eliminate the disproportionate effect of fines and fees on communities across the United States. There are over 20 states engaged in some form of bail and pretrial fine and fee reforms, and close to 30 states applying a fine and fee tool to make policy changes. At a local level, many are taking place in states like California, and states have launched studies with in-depth case studies examining the social and economic burden of fines and fees. PolicyLink initiated a 10-city initiative to support fine and fee reform.

Framing Policy Reform for Fines and Fees

The Pew Charitable Trusts introduced a framework to guide decision-making for state and local governments to improve community supervision. This can be done by reforming probation and parole procedures by suggesting the following:

- Alternatives to arrest, incarceration, and supervision: Divert low-risk individuals to social or health services instead of This can defer prosecution, allow community service as an alternative to imprisonment, and help to prioritize higher-risk individuals for the court system. Orleans Parish, Louisiana eliminated discretionary juvenile administrative fees, which includes those for probation supervision, physical and mental examination, care and treatment, appointed counsel, medical treatment, teen or youth court programs, and deferred disposition agreements.34 Several California counties stopped collecting juvenile fee debt and waived existing debt.35

Graduated sanctions for probation is a strategy used primarily to reduce juvenile detention and includes an accountability-based graduated series of steps (including incentives, treatment, and services) applicable to youth within the juvenile justice system. It provides appropriate sanctions for every act for which a juvenile is adjudicated delinquent by inducing their law-abiding behavior and by preventing their subsequent involvement with the juvenile justice system. In Rock County, Wisconsin and Union County, North Carolina, the use of graduated sanctions for youth who violated probation has reduced detention admissions and average length of stay for all youth.36 Multnomah County, Oregon instituted a “sanctions grid” for probation violations that minimized staff inconsistencies while encouraging sanctions other than detention.37 Rewards and incentives grids should be used in conjunction with the sanctions to promote positive reinforcement.

This also includes reclassification of offenses, much of which is under state control. Select misdemeanors may be reclassified as civil infractions — noncriminal violations of rules, policies, or laws for which people cannot be jailed — or simply legalized. Many jurisdictions treat drug possession as a felony. In some cases, trace amounts of a substance can result in a felony conviction, supervision, and even a prison sentence. In recent years, however, an increasing number of states have adopted reforms that reclassify and redefine certain drug crimes. Between 2009 and 2013, more than 30 states reformed their drug laws, reducing the maximum allowable prison terms for certain felony drug offenses, downgrading felonies to misdemeanors, and sometimes eliminating a supervision term in its entirety.38

Local leaders are also leading the charge, including a growing number of “progressive prosecutors” who are advancing policies to improve public safety and reduce mass incarceration. For example, in February 2021, Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosley announced permanent adoption of policies preventing prosecution for minor-level offenses (e.g., minor drug possession, prostitution, and minor traffic offenses). The policy resulted in decreases in arrests, a 20% reduction in violent crime, and a 36% decline in property crime.39 Additionally, there were 13 fewer homicides than during the previous year.40 The announcement also cited data from the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services indicating an 18% decline in the incarcerated population in Baltimore City during the COVID-19 pandemic and a corresponding 39% decrease in people entering the criminal justice system, compared to March 2020.

San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin prohibited his staff from using California’s three- strikes law to increase sentences. In Portsmouth, Virginia, Commonwealth’s Attorney Stephanie Morales committed to reducing bias in the criminal justice system and decriminalizing misdemeanor drug possessions. In Cook County, Illinois, State’s Attorney Kim Foxx implemented a suite of reforms, including raising the threshold for felony charges of retail theft to $1,000 and increasing the use of diversion programs as an alternative to incarceration by 25%.

Legalizing or decriminalizing marijuana use and possession is another policy strategy gaining traction at both the state and local levels to address inequities in policing, reduce the prison population, and stimulate the local economy. Nearly 100 localities in over a dozen states have enacted municipal laws or resolutions that either fully or partially decriminalize minor cannabis possession offenses.41 Additional citywide ordinances have passed in states that later decriminalized or legalized marijuana.

- Risk and needs-based policies: This enables parole and probation officers to use validated assessment tools to develop case plans tailored to individuals based on their level of risk of reoffending and help to determine their sense of need. This may also facilitate case load management of parole and probation officers. Washington, D.C., has long relied on risk assessment tools to determine who is detained pretrial. District attorneys in Brooklyn and Manhattan in New York City, and Philadelphia removed cash bail for low-level offenses and ordered prosecutors not to request bail in most misdemeanor cases. Multnomah County, Oregon developed a risk assessment instrument (RAI) used for criminal justice decision-making. In Oklahoma City, probation officers applied an evidence-based program and concentrated control and correctional resources on high-risk offenders. Individuals supervised by probation officers with smaller, more manageable caseloads are shown to receive more successful experiences with correctional interventions, leading to improved probation outcomes.

- Adopt shorter supervision periods, center on goals, and utilize incentives: This strategy can help reduce the time spent managing long probation periods, which have been shown to not deter additional offenses being committed. Parole and probation officers can be encouraged to adopt and/or increase incentives and minimize the volume of rules and regulations, thereby providing opportunities for enhanced case management. Arkansas passed a law in 2017 allowing for low-level or low-risk individuals violating parole to be sent to short-term facilities or to treatment programs as an alternative to sending them to prison.

- Individualize conditions for managing financial obligations: Community corrections are supported by the fines and fees formerly incarcerated individuals are mandated to pay. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, recommendations should focus on affordable, reduced, or eliminated fines and fees; prohibiting suspensions of driver’s licenses; and considering alternatives to financial payments. Ottawa County, Michigan reduced jail fees associated with duration of incarceration; fees went from$60 per day to a one-time flat fee of $60. In 2020, Dallas County reduced jail phone call fees, eliminated fees for setting up inmate accounts, and reduced third-party vendor fees. St. Louis County’s jail fee ordinance eliminated booking fees, bond fees, and fees related to providing medical care for incarcerated persons, and waived $3.4 million in outstanding debt.

- Reduce pathways to incarceration: Supervision revocations ensure that probation officers must assess people under their supervision for their risk of reoffending and adjust depending on this assessment. According to The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Supervision revocations, especially for technical violations, are a major driver of costly jail and prison admissions, and even short jail stays can create serious hardships for individuals, including loss of employment, decreased wages, housing insecurity, and family instability.”42 This policy seeks to advance standard definitions of technical violations (of parole and probation), minimize arrests for these violations, and maintain continuity of care and access to social and health services. Instead of eliminating incarceration for technical violations, several states have implemented revocation caps on the number of days a person will serve for probation and parole violations. State examples include Missouri and Louisiana. At the local level, San Francisco City and County provides persons experiencing homelessness with an option to clear “quality of life” citations if they receive 20 hours of social service assistance. Quality of life charges are issued for infractions like loitering or sleeping on a sidewalk and are often given to people struggling with homelessness.

Other policy strategies providing re-entry support include the use of transition specialists, providing a continuum of health treatment, and maintaining treatment for substance use and behavioral health issues.

- Support community supervision services: Policymakers should consider the role that community supervision organizations can play in their ability to shape the workforce, adopt evidence-based strategies, monitor and assess agency performance, and allocate funding based on evidence-based strategies.

Promise for Improving Health and Racial Equity

These policies can greatly reduce the number of people entering the carceral system. For the formerly incarcerated, it can reduce their chances of re-entry into the system and lifts the burden of government-sanctioned debt that creates financial hardships, preventing them from exercising their full rights (see Voting below). Further, the reduced financial burden of fines and fees for those incarcerated and for those who are under community supervision pro-grams can lead to:

- State and local savings: It is estimated that a collective national savings for states and localities would be close to $7.2 billion 43 The 2014 passage of Proposition 47 in California projected to save the state up to $1 billion over a five-year period and to direct those funds to substance use and mental health programs and services.44

- Reducing unemployment, enhancing the workforce, and boosting the economy: The annual GDP has the potential to increase by $65 billion by avoiding employment losses of those with criminal records.45 Other savings can be calculated by investing in education programs in prisons. Every $1 invested in prison education programs reduces incarceration costs by $4-$5 during the first three years post-release of a prisoner.46

Feasibility

A key barrier to the reforms being proposed is that many state and local courts, jails, and prisons rely on fines and fees as a source of revenue. With dwindling coffers due to the COVID-19 pandemic, reducing or eliminating these fees and eliminating that revenue source may be challenging. In addition, some city and county government leaders may be unaware of the negative impacts caused by fines and fees, presenting an opportunity for public health and community-based and criminal justice advocates to elevate the influence these fees have on local health and economy.

Immigrant-Friendly Policies and Practices to Promote Equitable Opportunity

The United States is built on immigration. Early settlers arrived to America from Europe, colonizing the land and inviting immigration from fellow Europeans. Fast forward to the present, immigration now holds negative stigma even though its purpose is no longer to colonize land but to have the opportunity to live in it. The false belief in a hierarchy of human value shows up in immigration through the stigmatization of immigrants of color, especially immigrants from Mexico and other countries in Latin America. Immigrants of color face racism and discrimination for moving to a land of opportunities and “freedom.” Immigrants account for 13.7% of the U.S. population and 23% of them are undocumented persons.47 It is important to acknowledge that the pathway to citizenship is not easy and attainable to everyone. Undocumented immigrants live in constant fear of being separated from the family they have created in the United States. They aren’t supported by federal policies and privileges that others are granted, such as health insurance or government benefits. Even though some cities are not welcoming to immigrants, others have adopted policies that have made them safe havens for immigrants.

Policy Examples

- Sanctuary policies: These are a range of policies that protect immigrants from potential deportation when reporting crimes, shielding local law enforcement from liability, and allowing states, counties, and cities to determine how they should allocate their resources. Sanctuary cities like Los Angeles prohibit local officials from questioning an individual’s immigration status. Birmingham, Alabama, has passed a resolution indicating that the police would not be a source for federal government and would be open to granting business licenses to all immigrants. In addition, Chicago has various laws that halt investigation of residents’ citizenship status. Sanctuary policies aim to restore trust between the community and local enforcement to address the real concerns of safety in neighborhoods. These few examples show the ways that cities try to protect the undocumented community.

- Welcoming City plans: Welcoming Cities are inclusive of all individuals, regardless of their immigration status. These cities implement policies, plans, or programs that help empower undocumented immigrants. Nashville, Tennessee, a Welcoming City, has put up billboards throughout the city stating: “Welcome the immigrant you once were.”48 This powerful message attempts to build a connection among individuals, thus strengthening the Some of these cities have intentionally created offices to serve “new Americans.”49 One of the sectors that most, if not all, Welcoming Cities focus on to support undocumented immigrants is employment and business.

Chicago implemented the Chicago New Americans Plan, which recognizes and acknowledges undocumented immigrants and includes several economic initiatives, including enhancing immigrant entrepreneurship. These resources are crucial in granting immigrants the ability to provide for themselves but also demonstrate that they are important contributors to the city’s economy.

Dayton, Ohio, implemented the Welcome Dayton Plan, supporting the integration of immigrants through a series of services such as encouraging business and economic development. This could entail working with entities such as the city’s Small Business Development Center to help immigrants overcome barriers when starting a business. The plan attempts to identify and deal with the concerns that individuals may have, such as accessing small loans for businesses. Most importantly, these plans create connections between immigrants and existing resources from community organizations, private entities, and other city and government offices.

Evidence of Improving Health and Racial Equity

Being a sanctuary city is not only beneficial to undocumented residents but also to the community overall. Sanctuary cities have 35.5 per 10,000 fewer crimes committed compared to non-detainer (areas that will support ICE if a warrant is presented) counties.50 Additionally, two-thirds of the non-sanctuary cities have higher murder rates.51 Apart from the safety provided to the community, being a sanctuary city alleviates fear from the undocumented community, which positively impacts their health. Fear may prevent individuals from attending health facilities and receiving medical attention. This is critical, as chronic illnesses may be diagnosed at advanced stages. In fact, a study in 2012 reported that 40% of medical providers noticed that ICE activities exacerbate mental health problems like depression and stress.52 It is important to note that inclusive health policies within sanctuary cities allow for emergency shelters to allocate resources and support to the immigrant community.

Sanctuary cities are safer and economically stronger than non-detainer counties. Sanctuary cities tend to have statistically significant lower unemployment rates than non-sanctuary cities. This supports the city’s economy, as individuals are more likely to redirect the money gained toward local business, increasing the prosperity of the city. In addition, the employment-to-population ratio in sanctuary cities is higher than the employment-to- population ratio in non-sanctuary cities, indicating a stronger local economy. In fact, non- sanctuary cities that implemented 287(g) agreements granting limited immigration authority to state and local law enforcement face high costs for both state and local law enforcement agencies. Thus, being a sanctuary city not only helps against the depletion of resources, it also positively impacts the community.

Feasibility

A particular barrier to more cities, counties, and states becoming sanctuary cities is both federal and state preemption. Under the Trump administration, sanctuary jurisdictions were threatened with federal funding cuts. This would mean a loss in budget for much-needed resources and programs like Medicaid and education.

Voting Rights Protection and Expansion

The right to vote is fundamental to a democracy. However, for most of U.S. history, the right to vote has been exclusively reserved for white men. While women were granted the right to vote in 1920, it would be another 45 years before voting rights were expanded to include Black Americans. However, those rights are not guaranteed, and attempts to suppress the vote of people of color can be found over the decades. The Center for American Progress writes:

“In 2012, the national voter turnout rate among Black citizens exceeded that of white citizens for the first time in American history. But this was quickly followed by two devastating U.S. Supreme Court rulings that eliminated core voting rights protections and threatened to undo decades of progress toward a vibrant democracy. These rulings, combined with the continued existence of decades-old voter suppression and disenfranchisement policies, threaten the fundamental right to vote for millions of Americans.”53

Voter suppression is a form of structural racism influencing policies that directly affect community health. While many voting laws are controlled at the state level, local leaders are taking steps to ensure that more of its residents can exercise their civic duty and drive local decision-making.

Policy Examples

- Extending the right to vote in local elections to non-citizens: Voting rights are a facilitator of policies centered on racial justice at the local level through several historic initiatives granting non-citizens the ability to participate in the electoral process, some of which include extending voting privileges in local elections to non-citizens. For example, Takoma Park, Maryland changed its law in 1992 to allow participation in the city’s mayoral and council elections, regardless of immigration status.

Six towns in Montgomery County, Maryland, enabled documented and undocumented residents to participate in the electoral process, and other places are using similar strategies. In San Francisco, a new policy has passed allowing people to register to vote in school board elections, regardless of legal immigration status. This new rule allows for non- citizens under temporary status who hold visas or are granted asylum to play an active role in public school board elections. This is particularly crucial because 1 in 3 students in San Francisco’s public schools are members of immigrant families.

New York City allowed non-citizens to vote in local school board elections from 1968 to 2003, until it did away with elected school boards. The issue is also being discussed in Boston; Montpelier, Vermont; Portland, Maine; and many other U.S. cities.

- Youth voting: According to FairVote, young citizens are of driving age, work without restrictions on their hours, and pay taxes, so they should also have a voice in their local government in the form of r rights to engage in the political process. Research shows the ability of young voters to cast a meaningful vote (16- and 17-year-olds) and that they are as informed and engaged in political issues as older voters (voters above the age of 18). Lowering the voting age in local elections can also lead to more fairness among the constituents that elected policy officials are serving. Within our current system where young people are unable to vote until turning 18, some citizens won’t have a chance to vote for their mayor until they are almost Most of the Council of the District of Columbia, as well as Mayor Muriel Bowser, have already signed onto a bill that proposes lowering the voting age in Washington, D.C. Takoma Park, Maryland, bordering Washington, D.C., became the first jurisdiction in the country to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to vote in 2013. Following this policy change, several other progressive cities have followed suit, the largest being Berkeley, California. At present, cities have only lowered voting age requirements for local elections.

- Amendments to timing of local elections to encourage greater civic participation: In the United States, most elected officials are elected on days other than the official Election Day, therefore underpinning the importance of timing. Statistically, most local officials are elected by a politically active minority since far fewer voters turn out during off-cycle elections. Understanding this fact, some localities have put forth a concerted effort to align the timing of local elections with federal and state elections to improve civic participation. Systematically altering election timing has been shown to affect political outcomes. The lower turnout in off-cycle years enhances the effectiveness of mobilization efforts and makes non-representative groups proportionately larger in making decisions within local elective outcomes/results. Scheduling of elections can be “tactics designed to distribute political power” when interest groups and political parties can take advantage of the political process to control policy outcomes on the local and county level.

Some cities could use a municipal right to vote to pass felon re-enfranchisement, election day or universal voter registration, paper ballots, early and weekend voting, foreign language ballots, and other such ordinances for city elections to expand citizen participation and/or voter engagement.

- Restoring voting rights to ex-offenders: An estimated 6.1 million Americans are denied their voting rights due to disenfranchisement 54 Eleven states go so far as to deny voting rights even once a sentence is complete and/or create challenges to have voting rights restored, such as requiring a pardon. Those 11 states account for 50% of the disenfranchised population, in which Black Americans are overly represented. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures:55

- In two states (Maine and Vermont) and (newly) Washington, D.C., people with felony convictions never lose their right to vote, even while they are incarcerated.

- In 21 states, people with felony convictions lose their voting rights only while incarcerated and receive automatic restoration upon release.

- In 16 states, people with felony convictions lose their voting rights during incarceration, and for a period after, typically while on parole and/or probation, after which voting rights are automatically restored. The formerly incarcerated may also have to pay outstanding fines, fees, or restitution before their rights are restored as Such is the case in Florida, which passed an amendment in 2018 to restore voting rights for over 1 million Floridians with felony convictions. The state legislature that to get their voting rights back, felons needed to pay off all fines and fees related to their convictions. Millions in fines exist across the state, including $278 million in Miami- Dade County. This debt can inhibit the restoration of voting rights.

- Ranked-choice voting to encourage ballot reform: Ranked-choice voting (RCV), an electoral system that allows voters to rank candidates by preference on their ballots, with higher ranked candidates obtaining the vote, has been adopted by many states in recent For example, this method of voting has been adopted for statewide and federal elections in Maine and Alaska and implemented in over 20 cities for mayoral and city council races. FairVote notes that “allowing all municipalities to choose for themselves what form of elections best suits their communities creates smaller laboratories of electoral reform and, hopefully through success at the local level, state legislators can become climatized to the change.”56 If legislators are not convinced to implement this change, this method of voting may be a catalyst to support overall ballot initiatives.

To increase accessibility for persons with disabilities, localities can strengthen voting rights for people with disabilities under guardianship and ensure that accessible voting methods are always available to all voters in every election, in every state, such as drive-up voting implemented in Washington, D.C.

Evidence for Improving Health and Racial Equity

Civic participation is a determinant of health and is recognized as such by both national (e.g., Healthy People) and international (e.g., Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development) organizations measuring health and well-being. Participation in civic life improves social well-being through increased feelings of purpose, connection, and belonging, which in turn improve physical health. In a study of 44 countries, including the United States, voter participation was associated with better self-reported health.57 Another study found that I individuals who did not vote reported worse health.

Voting builds the political and social capital of communities, which is especially important for communities of color who have largely been disenfranchised. When larger numbers of people from certain communities and groups participate in voting, it translates into greater influence over determining who holds political power to advance policies that respond to the needs and priorities of their community. Thus, voting drives the policies that shape the social determinants of health and equity.

Feasibility

Voting rights are largely determined at the state level. Unfortunately, many state lawmakers have introduced restrictive voting bills into law, and these numbers are on the rise. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, as of March 24, 2021, state legislators have introduced 361 bills with restrictive provisions in 47 states, many of which seek to undermine the authority of local officials. 58 Nearly a quarter place stricter requirements on voter IDs, with some of the most restrictive bills coming out of Arizona, Georgia, and Texas. One of the bills passed on March 25, 2021 restricts the availability and hours of voting drop boxes and criminalizes the act of giving snacks or water to voters waiting in line at polling places in Georgia.

RESOURCES FOR MORE INFORMATION

A Guidebook to Reimagining America’s Crisis Response Systems: A Decision-Making Framework for Responding to Vulnerable Populations in Crisis

ENDNOTES: