By Kun Huang, Bin Chen, Zhiwei Zhang, Gao Liu

For the past three and a half years we have been investigating the joint effect of social capital and partisanship on COVID-19 vaccination rates using county-level data from the United States. The results of our research suggest that when it comes to vaccination rates, social capital may be a double-edged sword. In more liberal counties, stronger social capital seems to have been a social asset that encourages people to seek vaccination and results in a higher vaccination rate. In contrast, in more conservative counties where the past voting for Donald Trump reaches 71 percent and beyond, stronger social capital has become a social liability for public health by reinforcing residents’ hesitancy toward or rejection of vaccinations, leading to a lower vaccination rate. Our research underscores the need for reducing the salience of partisanship and investing in bridging and linking social capital in polarized communities.

For the past three and a half years we have been investigating the joint effect of social capital and partisanship on COVID-19 vaccination rates using county-level data from the United States. The results of our research suggest that when it comes to vaccination rates, social capital may be a double-edged sword. In more liberal counties, stronger social capital seems to have been a social asset that encourages people to seek vaccination and results in a higher vaccination rate. In contrast, in more conservative counties where the past voting for Donald Trump reaches 71 percent and beyond, stronger social capital has become a social liability for public health by reinforcing residents’ hesitancy toward or rejection of vaccinations, leading to a lower vaccination rate. Our research underscores the need for reducing the salience of partisanship and investing in bridging and linking social capital in polarized communities.

Other significant collective outcomes, such as political violence, could be contingent on the nuanced effects of social capital and partisan polarization. The mitigation strategies of replacing partisan animosity with shared identity and bridging and linking social capital in polarized communities may help reduce the odds of negative outcomes in our democracy.

Social Capital: Bonding, Bridging and Linking

The rising infection and death tolls in Fall of 2021 in the U.S. were likely avoidable, given that over 90 percent of COVID related hospitalizations and deaths were unvaccinated people.1 One important factor that has yet to receive sufficient public attention is the role of social capital in encouraging or hindering COVID-19 vaccination rates. Consistent with recent literature on the relationship between social capital and COVID-19 outcomes2,3, we have conceptualized social capital in three dimensions: bonding (in-group ties), bridging (inter-group ties), and linking social capital (vertical trust, or degree of trusting relationships with formal institutions and persons of authority) at the community/county level of analysis. While bonding and bridging social capital are based on horizontal ties in a community, linking social capital is embedded in vertical ties that connect residents, elected officials, and decision-makers, including medical experts and public health leaders. Trust in government helps residents make decisions involving safety-related behaviors in their daily lives—e.g., flying on airplanes, access to key public goods and responsive governance during and after crises.

Nuanced Effects of Partisanship and Social Capital

In the U.S., partisanship may play an important role in the relationship between social capital and COVID-19 vaccination rates, given the strong influence of partisanship on COVID-19 vaccination and death rates.4 The rate of vaccination against COVID-19 among Republicans flatlined at 59 percent, while 91 percent of Democrats were vaccinated by October 2021, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 Vaccinate Monitor. The counties that voted heavily for Donald Trump in the 2020 Presidential election have seen much lower vaccination rates and nearly three times higher COVID-related death rates than those that voted heavily for President Joe Biden.5,6

We believe that the partisan divide in COVID outcomes is a manifestation of ideological polarization. Polarization used to be strong among elites, including legislators and elected officials but less pronounced among the general public. However, American citizens increasingly dislike and distrust those of the other party or political labels—Democrat, Republican, Liberal, Conservative. Such affective polarization among the general public, coupled with polarized elites, could boost the salience of partisan identity during population health crises. Like an individual’s social identity, political identity is a salient individual characteristic that could interact with social capital in powerful ways in the politicized debate about COVID-19 vaccination.

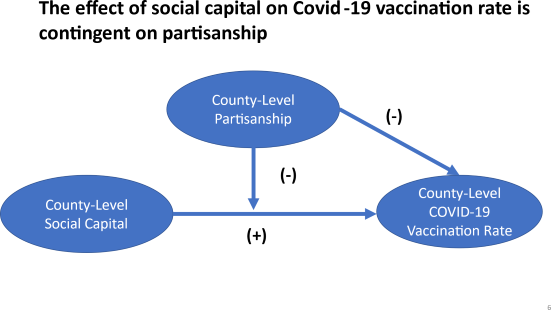

Clearly, social capital can be a double-edged sword. It can be productive or counterproductive in regard to the vaccination rate, depending on the partisanship through which it communicates, shares, and sustains, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Independent and Joint Effects of Social Capital and Partisanship

County-Level Social Capital and Partisanship

County-level cross-sectional data in the U.S. were collected and analyzed to test our conjecture. United States Congress Joint Economic Committee implemented the Social Capital Project from 2017 to 2022 in three phases.7 To measure the health of American communities, the Social Capital Project produced a county-level social capital index based on four components: three subindices and one stand-alone indicator. Subindices include the family unity subindex, community health subindex, and institutional health subindex. The collective efficacy is a stand- alone indicator that shows violent crimes per 100,000. The sampling frame consists of all 3,113 counties in the U.S. We found the social capital index is only available for 2,971 counties.

Partisanship was operationalized using the county-level rate of support for the Republican candidate in the 2020 presidential election. CDC’s COVID-19 vaccination rates for adults aged 18 and above at county level are the outcome variable. We controlled for the following county-level characteristics: socioeconomic, demographic, health and prior vaccine profile of residents.

CDC announced the Delta variant as the predominant strain of COVID-19 in the U.S. on August 6th. As a result, before August 6, 2021, the individual decision to get or not to get vaccinated was not complicated by the presence of the Delta variant. The logistical and other technical issues were smoothed out in early August 2021. The vaccine was also readily available to any eligible person willing to get the jab. Hence, we have chosen to use the August 1st, 2021, data point as the base for our primary analysis. We also expanded the time frame from April 1st to September 1st to see if we could detect any difference in the findings from the August 1st data.8 We find consistent results.

A Tipping Point of Partisanship

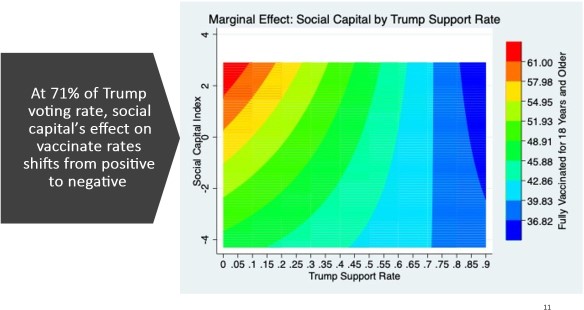

Figure 2: A Tipping Point for COVID Vaccination Rates on August 1st, 2021.

Figure 2 illustrates the interaction between social capital and Trump support rate as a function of COVID-19 vaccination rates. The graph on the left shows how the relationship between the two key variables changes the vaccination rate among adults. Starting from the origin, where Trump support was near zero, as the social capital index increases, the overall county-level vaccination rate also increased. However, as the Trump support rate rose, the positive impact of social capital on vaccination rates diminished, eventually turning negative when Trump support exceeded 71 percent, which was a tipping point that reverses the effect of social capital.9

Notably, we found that counties with a high level of social capital and a high level of Trump support had the lowest vaccination rates (Figure 2, NE Corner). Regions of high social capital, when joined with a high level of conservative partisanship, became social liabilities in terms of collective rejection of vaccination. The dark side of social capital manifested in a lower vaccination rate and likely higher death rate from COVID-19 in highly conservative regions.

Seventy one percent Trump support rate at the county level seems to be the threshold for the dark side effects to be salient.

In this configuration, social capital functioned as a hindrance to high vaccination rates, consistent with the dark side of the solidarity entailed in bonding social capital. Strong solidarity with ingroup members may reduce the flow of new ideas into the group, resulting in parochialism and inertia. As bonding social capital increases, a stronger ingroup/outgroup distinction becomes ingrained, potentially leading to increased outgroup hostility. This ingroup solidarity and outgroup hostility could be salient in the partisan divide of a county, generating a strongly shared partisan COVID-19 narrative.

Mitigation Strategies: Bridging and Linking Social Capital in Civic Life.

To reduce the liability of high social capital in highly conservative counties, trusted community leaders—e.g., physicians, churches, nonprofit leaders with deep local roots, etc.—may need to reach out at nonconventional sites such as funeral homes, radio shows, and churches. The key is to use respect and patience to answer questions and build bridging relationships with those harboring vaccine doubt. Resources should be used to fight online and offline disinformation, for example, by providing web-based training to primary care physicians to counter online misinformation.

Second, counties with a low level of social capital and high level of Trump support had the second-lowest vaccination rates (Figure 1, SE corner). We need to increase social capital to avoid the liability of partisan social capital. Care should be spent on bridging and linking social capital by increasing positive interactions, and relationships with pro-vaccine sources and local governing institutions, e.g., city and county governments, business associations, and school boards. Also, efforts to protect people’s privacy and reduce community shaming need to be strengthened so that people can get vaccinated without bringing attention and shame to themselves in their anti-vaccine community (i.e., provide discrete vaccination sites). Since the vaccine was politicized, it could be better to have in-person social interactions in a non- politicized way. The key is to reduce the saliency of partisan identity and replace it with shared community-oriented identity, e.g., religious, racial, or ethnic identity, to increase trust and cooperation. Rebuilding cross-party friendship ties could help bridge the partisan divide.10

Third, counties with a low level of social capital and a low level of Trump support had modest vaccination rates (Figure 2, SW corner). We need to increase the bridging social capital and the pro-vaccine message in the new networks. Partisanship is not an impeding factor here. Thus, increased convenience such as providing mobile vaccination vehicles, language, and cultural competence of vaccination personnel could be helpful. Native American communities had low levels of Trump support and low confidence in government institutions due to forced relocation and historical trauma. Nevertheless, they have strong family and community values. They achieved high vaccination rates early but stalled at around 60 percent in regard to full vaccinations. Perhaps non-Native-American counties can learn from the successes and challenges of the tribal community.

Lastly, counties with a high level of social capital and a low level of Trump support rate had the highest vaccination rates (Figure 2, NW corner). High levels of social capital and low levels of Trump support have produced high vaccination rates, but the vaccinated people may be angry toward those low-vaccination-rate counties in the same state or region due to concerns with unvaccinated COVID patients filling up hospital beds. Good listening and open-minded engagement facilitated by civil groups and/or trusted local government leaders would help restore social cohesion and shared identity.

References

1. Johnson, C. K., & Stobbe, M. (2021, June 29). Nearly all COVID deaths in US are now among Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-health- 941fcf43d9731c76c16e7354f5d5e187.

2. Elgar, J., Stefaniak, A., & Wohl, M. J. (2020). The trouble with trust: Time-series analysis of social capital, income inequality, and COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries. Social Science & Medicine, 263, 113365.

3. Fraser, , Aldrich, D. P., & Page-Tan, C. (2021). Bowling alone or distancing together? The role of social capital in excess death rates from COVID19. Social Science & Medicine, 284, 114241

4. Wood, , & Brumfiel, G. (2021, December 5). Pro-Trump counties now have far higher COVID death rates. Misinformation is to blame. NPR.

5. Wallace, J. , Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Schwartz, J. L. et al. Excess Death Rates for Republican and Democratic Registered Voters in Florida and Ohio During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):916-923.doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1154

6. Neil,S. & Dahai, Y & Elle, P & Ren, W & Dylan, R. (2022). The Association Between COVID-19 Mortality And The County-Level Partisan Divide In The United States. Health Affairs. 41. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00085.

7. Social Capital Project, United States Congress Joint Economic Committee , https://jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/socialcapitalproject

8. Z Zhang, G Liu, B Chen, K Huang, 2022. Social asset or social liability? how partisanship moderates the relationship between social capital and covid-19 vaccination rates across united states counties– Social Science & Medicine, 311:115325.

9. Macy, W., Ma, M., Tabin, D. R., Gao, J., & Szymanski, B. K. (2021). Polarization and tipping points. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(50).

10. Levendusky, M. (2023) . Our Common Bonds: Using What Americans Share to Help Bridge the Partisan Divide. University of Chicago Press.

Kun Huang is an Associate Professor of Public Administration and Population Health at the University of New Mexico

Bin Chen is a professor in the Austin W. Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, Baruch College, and a doctoral faculty at The Graduate Center, The City University of New York (CUNY).

Zhiwei Zhang is an Associate Professor at Department of Political Science, Kansas State University.

Gao Liu is an Associate Professor at School of Public Administration, Florida Atlantic University.