By Maja Viklands Harris

On January 2, 2025, the Portland City Council convened its first meeting of the year. The agenda was brief: adopting council rules and electing a council president. Yet the chamber quickly overflowed with testifiers and observers, all watching intently as the clerk called the roll.

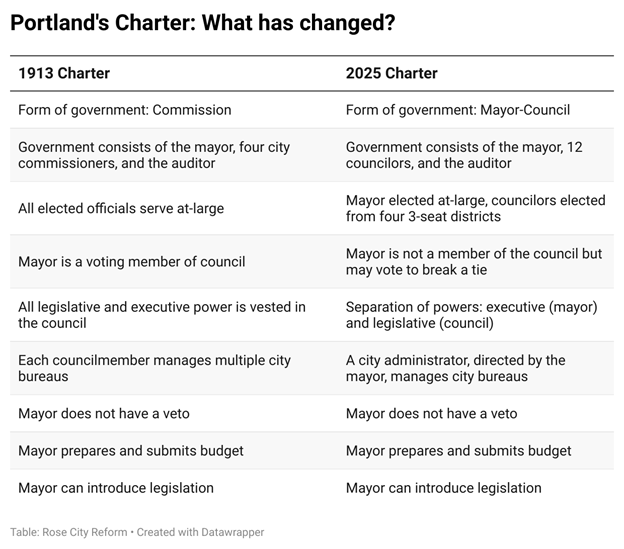

Why? This was the inaugural meeting of a brand-new government—every seat having been filled in the 2024 election. It marked the culmination of a two-year reform process that put every city office on the ballot, expanded the council from five to twelve seats, and ended Portland’s century-old commission form of government.

Even more notably, Portland is now the only major U.S. city to elect its council through proportional representation.

MULTIMEMBER DISTRICTS: DIVERSITY BY DESIGN

Most cities elect one council member per district, meaning only the top vote-getter gets a seat. Portland’s system works differently: four council districts each elect three representatives. The effect is a new political landscape where one candidate’s victory does not preclude another’s. It also means representatives from the same district may hold diverse—even contrasting—viewpoints.

“It’s challenging—in a good way,” says Elana Pirtle-Guiney, a former gubernatorial advisor who emerged from that historic first meeting as council president.

“In District Two, my district, we have three very different people elected. I think we see different constituencies as having elected us, and we bring different values to the table. We also feel a responsibility to work together on behalf of our district. Some votes are a challenge, but I think that’s good for the people we represent.”

Pirtle-Guiney says balancing policy objectives is part of the council president’s role. To that end, she led an effort to form eight policy committees tasked with debating key issues before they reach the full body. Committee meetings are broadcast and open to the public, allowing constituents to follow along and provide input.

“I try to bring as many opinions to the table as possible to create the best policy,” Pirtle-Guiney says.

Portland’s new mayor, Keith Wilson, thinks that’s what Portlanders were asking for when they passed a sweeping ballot measure to overhaul city government in 2022.

“People were craving change,” he says. “They wanted a more representative government, and they wanted a voice in the day-to-day decisions at City Hall.”

Portland City Council President Elana Pirtle-Guiney (left) poses for reporters with district colleagues Sameer Kanal (middle) and Dan Ryan (right)

THE RETURN OF A FORGOTTEN VOTING METHOD

The November 2024 election marked the debut of Portland’s new electoral system, featuring ranked choice voting for all offices. While ranking candidates is increasingly common—San Francisco and New York are prominent examples—Portland stands out for combining ranked ballots with multi-seat districts.

The technical name for this system is single transferable vote (STV). Sometimes called proportional ranked choice voting, STV is a form of proportional representation, allocating multiple seats based on the level of support candidates receive. Once recommended in the National Civic League’s Model City Charter1, STV has historical precedent in about two dozen U.S. cities, including New York City from 1936 to 19472. Though largely forgotten, some election reformers now call for its revival as a way to reflect political, cultural, and demographic diversity within districts.

One of STV’s defining features is that candidates don’t need a majority to win. The election threshold is tied to the number of seats available—the more seats, the lower the threshold. In Portland’s three-seat districts, candidates need just over 25 percent of the vote—sometimes less—to secure a seat.

This change had a particularly dramatic effect in a city where council members were previously chosen in citywide, single-seat races—the highest possible bar for election. In the 2024 election, candidates took notice: drawn by a more level playing field and the rare opportunity of every seat being open, a record-breaking 98 candidates ran for council, while 20 entered the mayor’s race.

The record-breaking candidate pool made for a unique campaign cycle that was equal parts exhilarating and overwhelming for the city’s approximately 468,000 registered voters. In two districts, the ballot listed as many as 30 names. With multiple seats available in each district, many candidates joined forces and canvassed together. Interest groups published slates supporting groups of candidates in the same district, sometimes in a specific ranking order, but typically not.

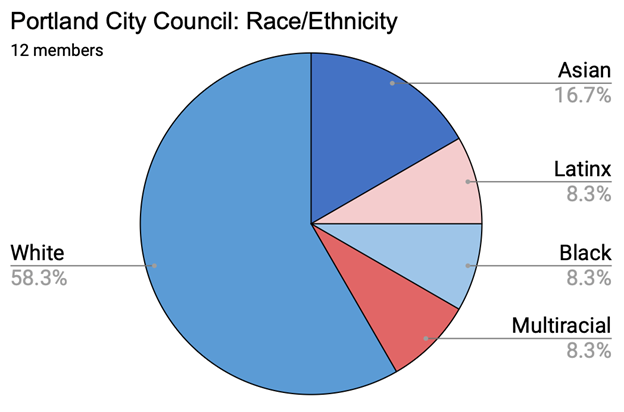

The outcome? Women won 50 percent of the seats. A third of council members are members of the LGBTQ+ community. Candidates identifying as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) make up 42 percent of the council—including the first two Asian-American representatives in Portland’s history.3

The new legislative body is also significantly younger than its predecessor. Millennials (born 1981–1996) hold 67 percent of seats, the first time any member of this generation has served on the council.

In an overwhelmingly progressive city, political diversity saw a more subtle shift. Though city races are nonpartisan, all members are Democrats. However, the expanded council now represents a broader range of viewpoints within the progressive spectrum, including three members affiliated with the Democratic Socialists of America. Councilors hold differing views on key issues like homelessness policy and the role of law enforcement.

“It’s pretty hard to argue that this new city council doesn’t reflect the people of Portland,” says Jenny Lee, deputy director of Oregon’s Coalition of Communities of Color.”

“No system is going to produce a perfect mirror image of the city’s demographics, but this is the most diverse council we’ve ever had—racially, gender-wise, and in terms of political perspective.”

MORE DIVERSITY, MORE STABILITY?

Lee says proportional representation is a gamechanger for Portland’s communities of color. In a city where roughly a third of voters identify as BIPOC, at-large elections meant no candidate of color could win without support from the white majority. According to Lee, a traditional district system wouldn’t have changed that, because no single area of Portland has a high enough concentration of racial minorities to form a majority of voters in any district.

“Even if you drew the best possible districts, the BIPOC population would make up 36 percent4 at most—and that’s lumping all communities of color together, which isn’t a great way to think about truly reflective and equitable political representation,” she says.

Lee believes the new system gives racial minorities a better chance of electing their preferred representatives—and keeping them. The same is true for any group that has repeatedly felt boxed out of political power, she says.

“For communities that have never had real, sustained political influence, this system makes it possible to have a seat at the table, not just for one election cycle, but long-term. With proportional representation, you’re not just creating more representation, you’re also creating more stability. There’s always a mix of perspectives at the table, which means we’re more likely to get real engagement across political differences, both on the council and for Portlanders as a whole.”

APPETITE FOR CHANGE

Many efforts to change voting systems are petitioned by advocacy organizations. Portland’s reform process took a different path. Adopted in 2022, the reform measure was designed and referred to the ballot by the Portland Charter Commission, a citizen-led body convened every ten years to review the city charter. Although the proposal faced pushback—including from politicians in office at the time and Portland’s chamber of commerce—58 percent of voters approved it.

“I think our success hinged on the buy-in we got from the community,” says Candace Avalos, a former charter commissioner who now serves on the council. Over the course of a year and a half, the commission held over 80 public meetings, nearly 30 community listening sessions, and received approximately 1,600 public comments.

“We gave people opportunities to voice their thoughts, and we showed them how their thoughts were being incorporated into the decisions we were making,” Avalos says.

Beyond expanding the council and changing how city leaders were elected, the measure repealed Portland’s commission form of government. Adopted in 1913, the system granted the mayor and four city commissioners shared executive power, with each overseeing their own set of city bureaus. The system lasted longer in Portland than in any other major city, surviving eight repeal attempts. By 2022, however, both the public and officeholders had grown frustrated with the fragmented leadership model. Portlanders often joked that City Hall had “five mini-mayors”—each pulling in a different direction.

“Our performance had been strained for a while,” says Mayor Wilson, a former trucking executive and first-time officeholder.

“The commission form of government had reached its limit in terms of growing with the city, especially given the major challenges we were facing,” says Wilson, who prevailed over three outgoing city council members on an ambitious promise to shelter the city’s 5,000+ individuals sleeping outside.

A WORK IN PROGRESS

Unlike his predecessor, Mayor Wilson does not serve on the council. Portland now operates under a mayor-council system, with separation of executive and legislative powers. Yet Wilson says building relationships with council members is a priority, not least to drum up support for his plan to address what he calls a “humanitarian crisis” on Portland’s streets.5

“There’s a lot of uncertainty with something new, and I’ve always believed that in those situations, you need to over-communicate,” says Wilson, who is known for his upbeat demeanor—described by one councilor as giving “Ted Lasso vibes”6.

“I’ve made it a point to visit all twelve councilors, explaining exactly what’s going to happen the next day, the next week, or further out. As we go through reorganization, I’ve had every councilor in my office discussing the details, so they understand the reasoning behind our decisions and the outcomes we’re expecting.”

Interim City Administrator Michael Jordan, who oversees day-to-day operations under Wilson’s direction, agrees:

“Even before the new council arrived, I believed that the most important norms to establish are collaboration, transparency, and communication,” he says.

Jordan notes that the transition is happening under difficult financial circumstances. Portland is facing a $93 million budget gap in the general fund, which supports everything from police and firefighters to parks and homeless shelters.7

“If this had happened five or ten years ago, we could have taken multiple years to go through a set of deliberative organizational and structural changes,” he says.

“This year, we find ourselves in a fiscal situation where we not only must do organizational change, but that change needs to produce efficiencies and reduce our footprint. That has heightened the sense of urgency and, to be fair, created a level of anxiety among our staff.”

Jordan says the outgoing council deserves credit for dedicating resources to ensuring a smooth transition, even though most of its members opposed the reform measure. He says their efforts helped the incoming government hit the ground running.

“I think it’s going well,” Mayor Wilson says. “We’re taking quick action on the city’s crises without needing to retool everything—we’re just fine-tuning.”

“WE’RE HERE NOW.”

Candace Avalos says the city still has a long way to go to live up to Portland’s motto, “the city that works.”

“Bureaucracy doesn’t like change,” she says. “People’s desks didn’t even move. I still see the city as being siloed in a lot of ways. That culture change is what we have to work through—and I think we’ll be successful, but it’s going to take time.”

Avalos believes the biggest change the public will notice is the presence of representatives in their neighborhoods. Under the previous at-large system, council members could live anywhere in the city, and most chose to live in Southwest and inner Portland. Only two had ever resided in East Portland, home to the city’s lowest-income and most racially diverse neighborhoods. In the 2024 election, the area—now its own district—gained three representatives. That’s more than in all the years combined since its annexation into Portland in the 1980s.

Avalos is one of those council members. During her canvassing efforts, many voters were surprised to find her at their door, she says, having never been visited by a political candidate before. A recent survey also found that East Portlanders voted at lower rates in the city election and expressed more confusion about the new voting method.8

Avalos sees an opportunity to change that.

“That’s going to be the real work going forward,” she says. “Meeting people where they’re at—on their doorsteps—saying, ‘Hey, we’re here now.”

Maja Viklands Harris is the founder of Rose City Reform, a journalism and research project dedicated to tracking Portland’s reform process. She is also the host of the Stump Talk podcast, where she interviews elected leaders and political experts about Portland politics.