By Adolf G. Gundersen

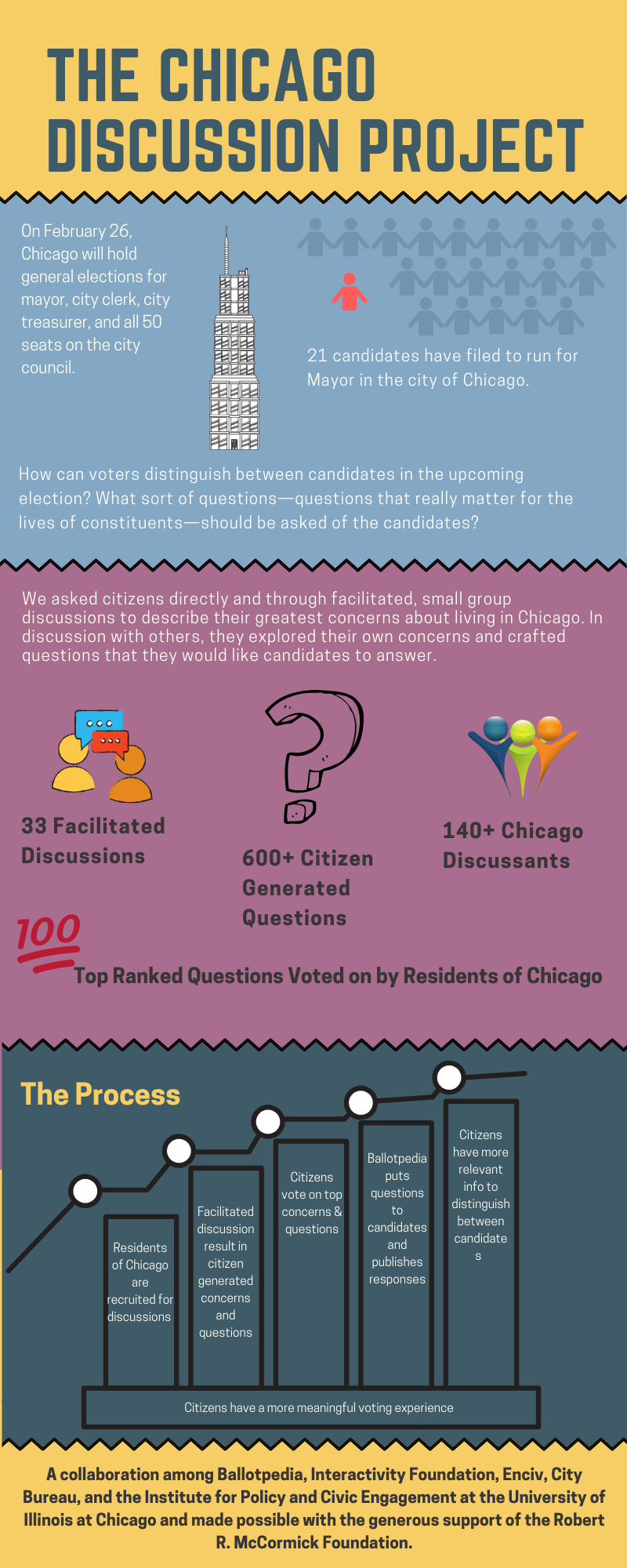

In 2018, citizens, journalists, and politicians were all involved in an innovative effort to use public deliberation to improve the quality of online media coverage for Chicago’s 2019 municipal election, an effort that reached hundreds of thousands of voters.

Expanding on a successful pilot project in Des Moines two years earlier, and funded by the McCormick Foundation, the 2019 Chicago Municipal Election Discussion Project was a four-way collaboration between EnCiv, Ballotpedia, the Interactivity Foundation (IF) and City Bureau.

EnCiv was founded by a team of independent developers in 2017 with the goal of building an integrated online collaborative platform and a network of organizations to support and benefit from it. (Among the network’s most important benefits is to enable collaborative efforts like those exemplified by the Chicago project. ) Since launching in 2007, Ballotpedia has been committed to balanced, one-stop online electoral coverage and is now among the country’s leaders in providing that service.

IF has pursued its mission of expanding and enhancing exploratory civic discussion since 2002 and, in the process, positively affecting the civic skills, temperament, and habits of thousands of citizens. City Bureau, founded in 2015 and based in south Chicago, works to “bring journalists and communities together in a collaborative spirit to produce media that is impactful, equitable and responsive to the public.”

How the Project Unfolded

In the summer of 2018, IF began recruiting residents for exploratory discussions, the goal of which was to elicit questions to ask candidates in the spring 2019 municipal election. Participants then ranked and edited a list of the questions using “All Our Ideas,” a robust software program designed expressly for this purpose. Ballotpedia posed the resulting short list of 24 questions to the candidates and then posted the candidates’ responses on its website for public viewing.

Infographic by Shannon Wheatley Hartman

Infographic by Shannon Wheatley Hartman

Recruiting. The Chicago municipal discussion project began with recruiting participants for the discussion sessions that would generate candidate questions. The recruiting effort involved multiple channels: on-the-ground contacts by a local recruiter, websites and newsletters, email lists, on-the-street canvassing, social media (both general and targeted), and phone calls. Of these, the most productive was our local recruiter, who alone accounted for slightly more than a third of our participants and a like proportion of the “disengaged” participants we sought to over-represent in our participant pool.

Project discussants numbered 144, a pool large enough to achieve a diverse cross-section: demographically, politically, and in terms of political engagement. As important, it over-represented the less well-off and the politically disengaged—recruiting criteria that embodied the project’s norm of “discursive affirmative action.” Although this number fell short of our original target, it did not compromise project outcomes which, by design, depended not on polling a statistically representative sample, but rather on engaging a diverse cross-section of citizens in exploratory discussion—the distinctive feature of the project.

We achieved less success in recruiting for political balance. However, this partial failing was significantly ameliorated by engaging participants in ranking the final questions in importance. It also must be judged in the context of the project’s positive outcomes—both the variety and authenticity of the questions it generated and the rigor with which participants ranked the questions (analyzed below in the section entitled “Lessons Learned”).

Discussion Sessions. IF developed and distributed to all seven project facilitators an exploratory discussion template or “script” based on hundreds of previous discussions in order to ensure quality and consistency in the conduct of the discussion sessions. Although 23 of our discussants participated in brief one-on-one conversations lasting shorter periods, 121 participated in discussion sessions with groups of 6-8 participants lasting either 30 or 90 minutes.

In the end, about one in six sessions was held online (with technical back-up supplied by EnCiv), inverting the ratio projected in the project design.

Project Editor Distills Question Pool from 600 to 100. All told, the discussion sessions produced an excess of 600 questions. The project’s chief editor then narrowed them down to 100 questions by eliminating redundancies, removing questions that were too general to elicit divergent responses (e.g., “What’s your position on education?”), and combining some questions into question sets.

Participants Rank Candidate Questions. Participants then ranked the edited list of 100 questions using “All Our Ideas” (AOI), a randomized, pairwise voting software program designed at Princeton University. AOI was recommended and then deployed by a team with extensive experience in gaining public input for planning decisions at the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Institute for Policy and Civic Engagement. Participants were sent follow-up emails and invitations to vote on this platform. The vote stayed open for six days to achieve the greatest number of possible votes by the greatest number of potential voters. Participants could cast votes between randomized pairs of questions for as long as they liked. In total, 68 (or 47 percent) of our 144 participants voted on the AOI platform and cast 4,116 votes.

Ballotpedia Poses Questions to Candidates. The move from citizen deliberation to journalism occurred as IF handed over the ranked list of questions to Ballotpedia. Ballotpedia editors then created a candidate interview survey based on three criteria: compactness, comprehensiveness, and fealty to participants’ concerns. The resulting survey contained 24 questions representing the top-ranked participant questions in each of several topical areas.

According to data assembled by Ballotpedia, 178 candidates filed in 2018 across all Chicago offices. Ballotpedia requested survey responses from all but one candidate directly and from all of them via indirect means. Additionally, Ballotpedia advertised the survey on Ballotpedia.org, across all of its Chicago coverage, on its social media platforms, and in its Deep Dish newsletter about the Chicago election. Finally, Ballotpedia attempted to induce candidates to respond to the project-based survey by featuring early candidate responses on its website.

Candidates Respond. Forty-seven candidates (26.4 percent) completed the survey. This included four of the 14 mayoral candidates (28.6 percent), two of the three city treasurer candidates (66.6 percent), and 41 of the 160 city council candidates (25.6 percent). (The only city clerk candidate ran unopposed and did not complete the survey.) These numbers are relatively favorable when compared to Ballotpedia’s historic response rates. In 2018, Ballotpedia contacted 13,848 candidates in the country as a whole, achieving an overall response rate of 15.78 percent. Indeed, the 26.4 percent response rate was the highest the organization ever recorded for a large-scale outreach program.

To anyone reviewing the candidate responses from the perspective of a voter in search of discriminating information, two features are likely to stand out. First, the responses are highly engaging: candidates appear to be speaking to the reader personally rather than making a pitch to a crowd. Second, candidates are expansive and range widely in their responses, pulling few punches. As a result, the responses are rich in detail about the candidates’ background and values, their policy ideas and preferences, and how they would go about implementing their plans. A trio of candidate responses to the survey’s top-ranked question regarding income inequality and public schools illustrates these points:

We need a democratically elected, representative school board in order to address the disparities in educational opportunities between wealthier areas of the city and poorer ones. Under Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the current city council, the appointed school board has provided little constructive oversight for CPS [Chicago Public Schools], whose CEOs have either wound up in jail or resigned in shame over misconduct. We also need to change the per-pupil school funding formula. South and west side schools need more funding than their wealthier north side counterparts in order to hire more school counselors and provide more programs and services in economically impoverished areas. The one size fits all approach to school funding is simply not working. Candidate for City Council Pete DeMay

I believe we must solve these problems by investing heavily in all public schools, especially neighborhood schools. I just sent my first child to elementary school, and it was a stressful and painful process to decide where she should go. My wife and I live in a good neighborhood with good neighborhood schools, we are not impoverished, and we’re both familiar with the public schools from our own experiences attending them and my mother-in-law’s experience working in them. I personally went to four different public schools growing up as a result of being gentrified out of different neighborhoods, so I have a very personal experience that fuels my value set. We need to invest in schools equitably and fiercely advocate for an elected school board. The goal is for every neighborhood school to have the best world class education possible, regardless of what zip code it resides in. Candidate for City Council André Vasquez

Education is my passion, the foundation for my professional and activist work. I grew up in my continuously disenfranchised, underserved ward, even coming into contact with open gunfire. I have personally experienced the different trajectories lives can take based on educational opportunities. I attended an excellent public neighborhood elementary school, then Whitney M. Young Magnet High School. Less fortunate friends got pulled into negative outcomes, while I went on to earn an M.S. Ed. in Education Policy from the University of Pennsylvania, an M.A. in Teaching from National Louis University, and a B.A. in Political Science from the University of Michigan. Though I oppose opening more charter schools, I support schools doing good work, regardless of status. I will push charter schools to develop community school models. I will also pursue requirements that charter schools provide proof of their compliance of providing special education services to students with learning disabilities. Candidate for City Council Nicole Johnson

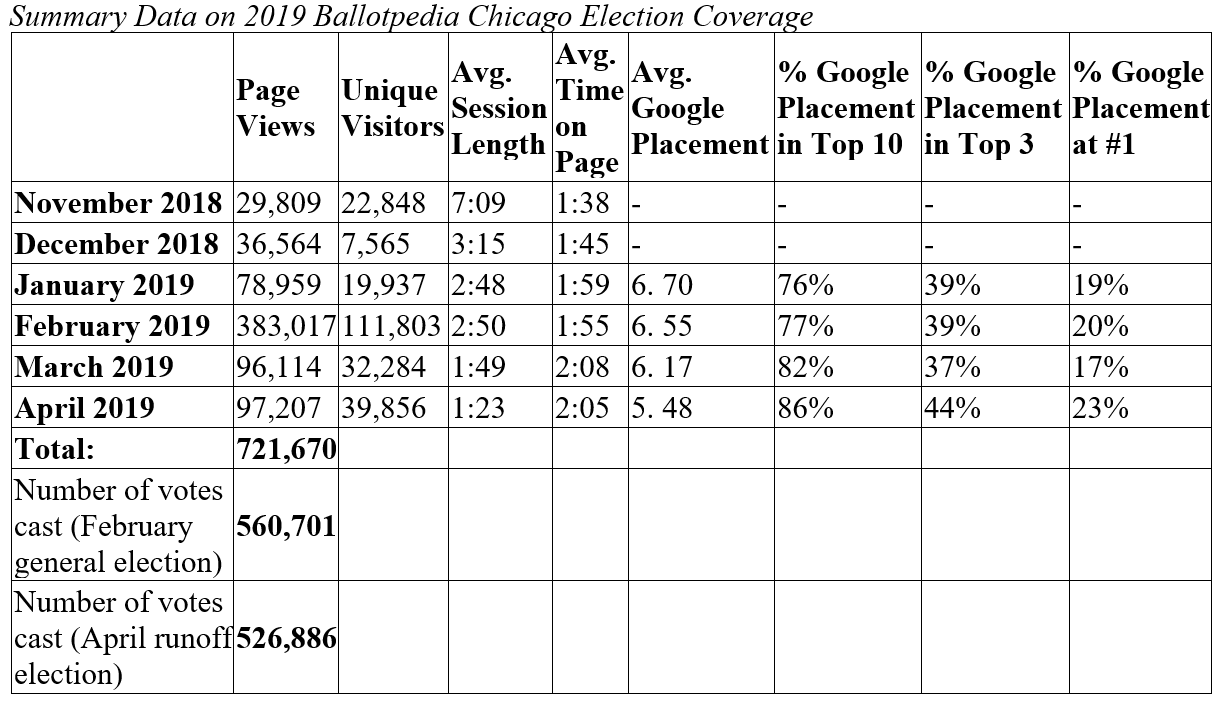

News Coverage Uptake. Below is a table with data tabulated by Ballotpedia on its Chicago election coverage as of April 2019. By comparison, Ballotpedia’s coverage of Chicago’s 2015 election resulted in 17,035 total page views of the coverage that year.

Lessons Learned

Recruiting. Engagement practitioners often report that recruiting is their biggest challenge. From IF’s perspective, recruiting proved to be this project’s biggest single success. (For all its challenges, recruiting yielded levels of participation and diversity unmatched by any project in IF’s 17-year history and significantly greater than the 2017 Des Moines Ballotpedia/IF pilot project on which the Chicago effort was modeled.) We drew three crucial lessons from this outcome. In order of importance, these lessons were the following:

- To prioritize the use of local recruiters able to draw on their own personal and organizational networks;

- To supplement local in-person recruiting with social media messages specifically targeted at “influencers” already engaged in topics of direct relevance to the project; and

- To simplify online registration procedures to improve the odds that online registrants actually participate. (Those responsible for organizing online sessions were unanimous in their view that scheduling issues and flagging interest contributed far less to the gap between online registration and actual participation than the requirement that participants install a separate video conferencing application.)

Discussion Sessions. Facilitators reported that all four types of sessions (longer in-person, longer online, brief online, and brief in person) were characterized by lively participation; participants graded the sessions 4.5 on a 5-point scale while criticizing the sessions mainly for being too short or too small. Most importantly, the number and diversity of participants and the quality of the sessions combined to generate the numbers and type of questions intended, as explained in the next several paragraphs.

Question quality. IF assessed the quality of the citizen-generated questions by evaluating the degree to which they did the following: (1) accurately reflected the content of voters’ concerns; (2) matched voters’ ranking of their concerns; and (3) proved capable of eliciting useful information from candidates. Question quality was high across all three metrics.

The questions resulting from the project were “accurate” both in the sense that they originated in verbal encounters with actual Chicago voters and that the voters represented a true cross-section of the city’s demographic and political diversity. (Participants’ original language choices were preserved to the greatest extent possible given the 140-character limit imposed by the AOI ranking tool.) Use of the AOI software program enabled participants to rigorously rank the distilled group of 100 questions in importance. Use of this tool ensured that we were not simply cataloguing questions but rather producing a list that reflected participants’ view of their relative importance. The accuracy of the questions was underscored about a third of the way through the discussion sessions when the rate at which new questions were being added rapidly began to approach zero.

Ballotpedia also found that the Chicago responses were of an unusually high quality, on average. In Ballotpedia’s experience surveying candidates and reviewing candidate responses to surveys distributed by other media outlets, candidates’ responses are typically of a pro forma nature—if they respond at all. Their responses to the Chicago project questions tended to be longer and more specific. This was similar to Ballotpedia’s experience working with IF on the smaller scale 2017 Des Moines school board project.

Response rate. Question quality—even in all the senses just described—would have been an empty achievement had candidates not responded to the questions in revealing ways. That candidates did respond—and responded as openly as they did—is a strong, if inexact, indicator of the strength of the questions.

Why did the project questions prove so powerful in eliciting revealing candidate responses? Project partners hypothesize that two factors were at work, both linked to the questions’ source (actual voters). The first is the simple reality that candidates ignore voters, specifically voters’ questions, at their own peril. Reinforcing this effect, voters’ informational motives diverge from those of journalists—a reality not lost on candidates who are frequently suspicious of reporters who may be intent on tripping them up or catching them off guard. Notably, although project participants posed plenty of challenging questions, we detected no “gotcha” questions upon reviewing either the original list of 600 or the final list sent to candidates. That voters must in general be answered and that their questions were non-threatening both influenced candidates to open up.

Both the rate and quality of candidates’ responses were clearly boosted by the direct connection the project established between voters and candidates—a connection created by a chain of activities that began in recruitment, ran through the discussions to question editing and ranking, and extended from there to candidate outreach. Each link in the chain mattered and thus helps to explain the rate and quality of the final responses.

News Coverage Uptake. Although Ballotpedia’s web traffic has more than tripled overall from 2015 to 2019 (and other elements of its election coverage quality also improved during that time), Ballotpedia believes that its partnership with EnCiv and IF was a key driving force behind the massive cycle-to-cycle growth in readership and engagement from 17,035 to 721,670 reported above. The candidate responses added a unique and compelling set of content across dozens of articles tied to the Chicago election.

The Chicago election coverage traffic data, especially when compared to Ballotpedia’s historical record, are a testament to the breadth of the project’s impact. At the same time, it is important to remember that other positive influences were almost certainly at work, including high levels of voter interest in a lively campaign (especially at the top of the ticket) and increased trust in Ballotpedia as a valuable and reliable source of election coverage.

Conclusion

Citizen-based reporting stands at the opposite conceptual pole from reporting mediated by either human agents or by machine algorithms. In traditional journalism, content is mediated by editors and reporters that make decisions about story lines, the questions they will ask, and how to present the results. Machine algorithms, long employed by social media sites and increasingly by traditional media outlets like the Chicago Tribune, use individuals’ own use patterns to mediate content, in the process creating or at least reinforcing the “information bubbles” that are notorious among deliberatively-minded democrats. On the contrary, the norm driving infogagement is to reflect rather than reinforce the views of those participating in the coverage. In practice, this means first and foremost giving citizens the power to frame stories and ask questions. When infogagement is itself deliberative, as in this project, an additional feedback loop is present: citizen deliberation impacts journalism, which then—at least potentially—impacts (subsequent) deliberation.

Although debate is certain to continue among scholars about whether and how deliberation “makes citizens better,” this natural experiment in local election coverage makes abundantly clear that deliberation can “make journalism better” in the terms that matter most to journalists, candidates, and hundreds of thousands of readers alike. The next step is, of course, to learn more about how candidates and readers actually make use of deliberatively-enhanced journalism like that produced by our Chicago project and to use those insights to improve future infogagement efforts. Fortunately, scholars have already laid the groundwork for such research. Researchers need only take advantage of these opportunities.

Political scientist Adolf G. Gundersen serves as Research Director of the Interactivity Foundation.