By Michelle Dennis

In the Winter 2024 issue of the National Civic Review, Nick Vlahos, Deputy Director of the Center for Democracy Innovation, began to look at how a combination of two Democracy innovations, Participatory Budgeting and Citizens’ Assemblies, might be used to empower the public. He called for a conversation to explore this possibility.1 I wrote this article to contribute to that conversation. I am going to suggest how combining these democracy innovations might modify the city budget process to give citizens a meaningful say in how their taxes are spent.

A Little Background on the City Budget Process

Cities are required by law to adopt budgets. Budgets express how revenues will be spent to accomplish service priorities of the community. The budget preparation and adoption process usually operates from November through June. The process culminates with the presentation of a proposed budget at a public hearing where members of the public are allowed to talk for three minutes each. Following the public hearing, the city council adopts the final budget.

Yes, sometimes cities have previously provided budget input opportunities to the public in the form of surveys, web sites to type in new ideas/services wants, focus groups, and now even use AI to discover what the public is concerned about by scanning social media. Almost always, these techniques are used to “check in” with the public to see if the development of the proposed budget is reflecting what is wanted.

If cities solicit input about new services or new service levels, it is rare for the professional staff and elected officials to get back to citizens to explain what input was used or not used and why. So, the public is then often left with: “Well, I gave my input, and no one talked to me about it, and I have no idea where to look in the budget document to see if they used my suggestion. It looks like no one really listens to me so why bother trying to participate!”

Most local governments post their proposed and adopted budgets online. It is usually a 300-700+ page document that almost no one in the community reads because cities have not taken the time to show the public how to read it or explain what the information means. Further, the budget document almost always shows how money will be spent on departments and other organizational units rather than on specific services or programs that impact citizens’ lives.

If at the end of the city’s fiscal year the city provides service performance results, the results are usually presented in a form primarily for the benefit of city program managers and usually are of little or no use to the public in terms of evaluating if the public got what they expected.

What city budget documents essentially present to the public is a plan created by city staff and elected officials about how they will spend the public’s taxes.

However, in the background of the city budget process, elected officials and staff have been grappling with what has been termed the basic budget question: “On what basis shall it be decided to allocate X dollars to activity A instead of activity B,” where the activities have been defined for the public. Further, it is almost impossible to judge one activity against another because there is no common denominator for both activities. 2

For over 100 years, budgeting professionals have worked hard to try to answer this basic budgeting question by revising the design of the budget process and/or the budget document, and by employing various technical analytical tools such as cost-benefit analysis. They have not been successful because from the perspective of the public they have been asking the wrong question.

From the perspective of the public, the basic budget question should be: on what basis shall it be decided to allocate X dollars between the outputs/outcomes of activity A and the outputs/outcomes of activity B where the outputs/outcomes sought and the dollar allocations are defined by the public.

Until now, professional staff and elected officials have been reluctant to turn over these decisions to the public primarily because democratic mechanisms have not been available to ensure that the resultant decisions represent the entire community. However, by combining the strengths of Participatory Budgeting and Citizen Assemblies, we now have a possible path forward.

Here is How this New Path Might Work

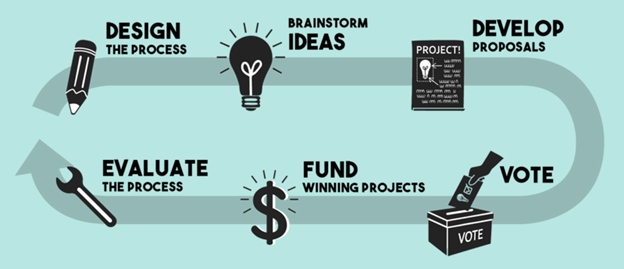

Since 1989, Participatory Budgeting has spread to 7,000 + cities around the world. In the United States, the first Participatory Budgeting process was in 2009 in the City of Chicago. It is now used in many cities and school districts across the United States. (6) It is a process where community members voluntarily come together to identify and express their opinion by voting on projects and/or services they want implemented, and to allocate a limited amount of public funds provided by the government. Usually, any member of the community above a certain age can participate in the process.

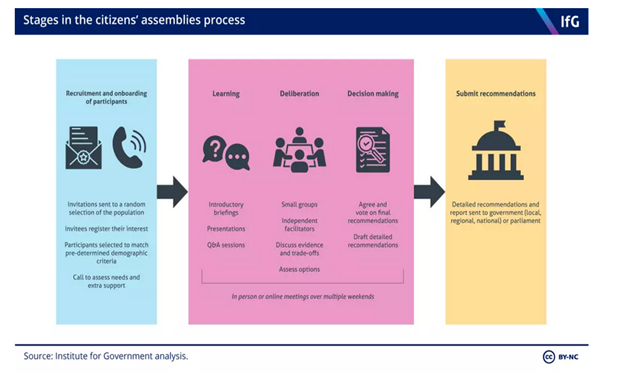

A Citizens’ Assembly is a randomly selected group of community members, representing the diversity of a community, brought together to deliberate and find common ground on matters of importance to the community. The community’s government can agree to implement the recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly, or it can agree to consider the recommendations. Deliberations are facilitated by factual input provided by experts at the request of the Citizens’ Assembly.

A recent Pew Research Center poll indicated that 79 percent of U.S. citizens were very or somewhat supportive of Citizen Assemblies where citizens deliberate issues and make recommendations about national laws.3 Petaluma, California is the first city in the United States that created a Citizens’ Assembly to deliberate successively about a major community issue. Members of Petaluma Citizens’ Assembly had a transformative experience participating in government decision-making. 4

By combining the Participatory Budgeting experience of voting on the use of public funds with the Citizens’ Assembly experience of deliberating rather than expressing opinions, we have a potentially powerful new democratic mechanism to define community desired service outputs/outcomes, and to allocate public funds to achieve those outputs/outcomes. Let us call this new democratic mechanism a Participatory Assembly for Budgeting (PAB).

The following is a possible step-by-step scenario to establish and implement a PAB that would be charged with making decisions or recommendations about how to spend tax revenues.

- Elected officials and city staff select a local government functional service area – e.g. Parks and Recreation – to be considered by the PAB.

- City staff breaks down the Parks and Recreation functional service area into discreet “on the ground” services already being delivered to residents – e.g. providing playing fields.

- City staff sends a survey to all city residents asking them to:

- List any discrete Parks and Recreation services that are NOT already being provided that would make a difference in their life if they were provided.

- Prioritize all Parks and Recreation Services ALREADY being provided, from MOST IMPORTANT to LEAST IMPORTANT.

- Elected officials create a PAB to:

- Prioritize the list of Parks and Recreation services NOT already being provided to the community using the citizen survey input and their own deliberations.

- Learn the details about Parks and Recreation services ALREADY being provided.

- Determine if any Parks and Recreation services NOT already being provided should replace any Parks and Recreation services ALREADY being provided that received a low priority on the community survey;

- Determine if any prioritized Parks and Recreation services NOT already being provided and NOT replacing any Parks and Recreation services ALREADY being provided should, nevertheless, be provided;

- Provide to City staff a master prioritized list of Parks and Recreation services NOT now provided and ALREADY being provided that should be included in the City’s budget;

- PAB asks city staff to determine the financial cost of the of the new master list of prioritized Parks and Recreation services.

- At a public hearing, PAB presents to the City Council the new master list of prioritized Parks and Recreation services for inclusion in the budget, or for the City Council’s consideration and approval, depending on what prior commitments the City Council has made to the PAB.

It is suggested that all city functional service areas eventually be reviewed by a PAB, and a PAB review be scheduled every five or ten years or as an on-going process.

It should be noted that implementing a PAB would change the primary driver of the city budget process. Now, almost always, the city budget process is driven by a projection of revenues for the budget year based on the existing revenue structure of the city (existing revenue sources, tax rates and tax bases). Then, proposed expenditures are “fitted into” the projected revenues. Using a PAB, the budget process is driven by needed/wanted services, and then how to pay for them would be considered.

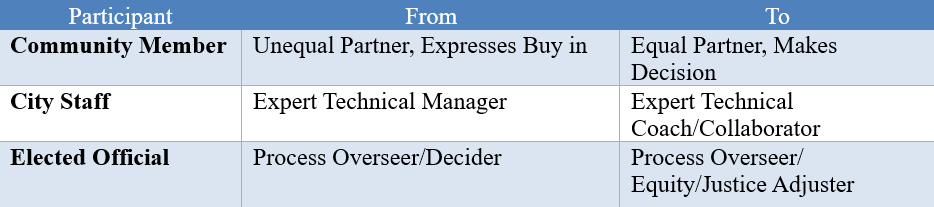

It should also be noted that implementing a PAB would alter the primary role of city budget process participants:

Successful implementation of a PAB benefits a city because:

- Asking the public to participate in a PAB would increase citizen trust and confidence in city staff and elected officials;

- Giving citizens a voice that is heard and matters; and

- Ensuring the mix of city provided services/service levels directly reflects how the public wants their taxes to be spent.

A PAB has not yet been implemented by a city; what city will be the first?

Michelle Dennis is a Certified Public Finance Officer. Prior to her retirement in 2003, she worked in local government budget and finance positions for almost 40 years. Since 2004, she has been teaching Public Budgeting and Finance at the UCLA Myer and Renee Luskin Graduate School of Public Affairs.