By Michelle Crandall

Local governments are taking lessons from technology and product development firms when it comes to examining ways to develop new services and revamp existing ones. Concepts of design-thinking and human-centered design are being adopted in cities and counties across the U.S. and Canada. This article will look at these “resident-centered design” concepts, answering what they are, how they are used, and how they can improve our relationships with our residents and ultimately improve the services, products and user experiences we choose to co-create. Also discussed are a city and county that are implementing some combination of these methods and what their successes have been and what they’ve learned along the way. Finally, I will offer thoughts on how an organization can begin using resident-centered design concepts and processes.

Cities, counties, towns, townships and villages in the United States have traditionally provided more avenues for resident engagement than is typically provided at the state and federal level. This makes sense when you consider that local governments are closer to those being served and are of a size and structure that better facilitates communication and involvement of residents. Historically, city council chambers and town hall meetings have provided opportunities for citizens to voice their opinions and speak directly with those they elect to represent them. Since the mid-1990s, the call for greater transparency and responsiveness through on-line technologies have further improved one-way and two-way interaction with residents.

What is Design Thinking and Human-Centered Design?

Design-thinking and human-centered design are closely aligned. Design-thinking is a creative problem-solving method that incorporates elements of understanding the end-user needs and experiences to develop a better solution or product. Design-thinking uses a five-step process: 1.) empathize with the challenges of the customer; 2.) define the problem; 3.) ideate solutions; 4.) prototype solutions; and 5.) test a preferred solution(s). The goal is to achieve improved product design by including end-user’s perspective. This perspective can be gathered through a variety of means, including user data, surveys, interviews and end user observations.

Human-centered design is an approach to design-thinking that further involves the end-user in the steps outlined above. It goes beyond gathering survey results, user data and/or customer observations to inform a design team’s thinking as they work through the process. Instead it puts the design team and the end-users in the same room co-designing a product or service. At the local government level, this translates into residents being closely involved in each step of the design-thinking process. Residents provide in-person input as to challenges and then help to define the core problem(s), brainstorm solutions and test prototypes. Implemented in this setting, human-centered design might more appropriately be called “resident-centered design.”

The Development of the Methods

First popular with product development firms and later with technology firms, design-thinking is now common and considered a best practice among these and many other business sectors. Local governments began experimenting with elements of design-thinking over the last decade. In the last 3-5 years thee ideas have been adopted by a small percentage of forward-thinking local government agencies. Influenced by both the successes witnessed in the private sector and by the demands of citizens now accustomed to goods and services that are customized to their needs, design-thinking and human-centered design could be the next big step local governments will take in the area of resident engagement. With advances in technology and more services being available on-line, today’s informed, digital citizens want their local governments to provide some of the same conveniences found in the consumer world of Apple, Amazon, Waze and Netflix.

Beyond this demand argument for implementing design-thinking is the simple truth that human-centered design provides a better experience for those being served. The process of involving residents from problem identification and ideation through design and prototyping allows for a greater understanding of what is needed and wanted by community members and allows for adjustments along the way to adapt service design and delivery.

Design-Thinking in Dublin, Ohio

In Dublin, resident engagement has always been a part of our DNA. The City of Dublin’s vision statement and strategic focus areas speak to it, and our operations embody it. With a population just under 50,000, the city has close to 3,000 residents and corporate residents who volunteer for the city each year in nearly every area of service delivery. “Learn, Serve and Engage” is the philosophy for the volunteers’ experience. We want each volunteer to learn about how his/her service is connected to the larger mission and to work alongside employees, gaining a strong understanding of our operations and organizational culture. This approach helps to build informed citizens and community advocates.

Additionally, residents are frequently asked to participate in land development and park design processes and are surveyed on an on-going basis to gauge their opinions regarding an array of issues and services. Finally, the city invests significant time and effort in educating residents and providing accurate and timely information. Transparent, frequent and comprehensive information sharing is critical for Dublin to build trust and understanding among our community members.

Defining Aging-in-Place Service Needs

Our first significant experimentation with human-centered design began as part of the implementation of the city’s aging-in-place strategies. In October 2016, city staff introduced an Aging-in-Place Strategic Plan to the Dublin City Council. Facing the same demographic shifts of many other U.S. cities, Dublin had a growing number of older adult residents. Census data showed that this number would only continue to grow over the next 20 years and survey results showed that many residents wished to remain in Dublin and in their homes as they aged. The strategic plan considered service, planning and infrastructure changes necessary to adapt to the needs of this growing segment of our population, now and in the future. The Dublin City Council referred the draft plan to a resident advisory commission that reviewed and revised the document, bringing a redrafted plan back for council acceptance in September 2017. In early 2018, during their annual visioning retreat, council-members requested that further resident input be gathered to validate the needs identified in the plan to ensure our implementation priorities aligned with resident priorities. This became an opportunity to gather resident input in a more comprehensive way and to begin using human-centered design concepts.

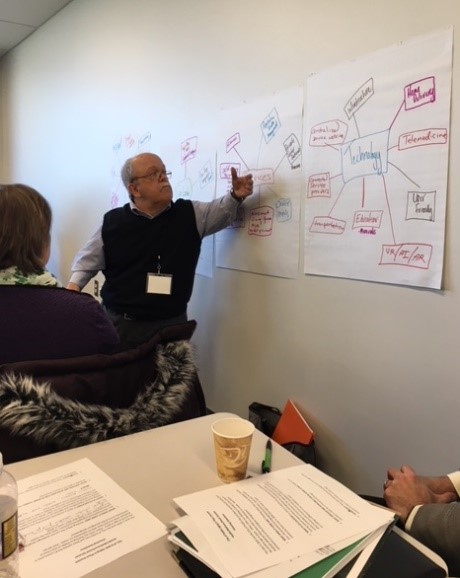

We began by reaching out to private sector, social service, non-profit and faith-based entities that provided services to older adults. While a few of these organizations had been consulted during the development of the plan, we had not brought a group of them together to explore the challenges of aging-in-place in Dublin. The city partnered with Ohio University’s College of Health Sciences and Professions to invite approximately 30 organizations to a half-day “Aging-in-Place Summit.” More than 40 people attended, representing nearly all 30 entities that were invited. In small groups, the participants were asked a series of visioning questions to design a community that would be considered the best place in the world to age in place. With the smaller groups reporting back out, further discussion occurred collectively with the larger group. Small and large group input was documented and kept, so that it could be compared to the feedback obtained from residents in the next phase.

We began by reaching out to private sector, social service, non-profit and faith-based entities that provided services to older adults. While a few of these organizations had been consulted during the development of the plan, we had not brought a group of them together to explore the challenges of aging-in-place in Dublin. The city partnered with Ohio University’s College of Health Sciences and Professions to invite approximately 30 organizations to a half-day “Aging-in-Place Summit.” More than 40 people attended, representing nearly all 30 entities that were invited. In small groups, the participants were asked a series of visioning questions to design a community that would be considered the best place in the world to age in place. With the smaller groups reporting back out, further discussion occurred collectively with the larger group. Small and large group input was documented and kept, so that it could be compared to the feedback obtained from residents in the next phase.

Next came a series of Community Conversations with residents. Two sessions were held specifically for caregivers and five sessions for older adults. Response to invitations to attend these conversations were positive with close to 300 residents attending one of the seven sessions. To assist City staff with these sessions, Cardinal Health, a Dublin-based company, offered two staff members who are trained ethnographers and part of the company’s Fuse product innovation center. Having these professional “listeners” and “observers” in the room was invaluable to later steps of understanding and organizing the input into possible prototype ideas. Similar to the agency summit, the participants were asked to answer the same series of visioning questions as part of smaller groups with a larger group discussion at the end. An additional first question was asked of these groups, inquiring as to “What brought you here?” This question proved to be the most telling of the residents’ emotions related to thoughts of aging and being able to remain in the community and their homes. Fear, frustration, anxiety and impatience for results were overwhelmingly evident emotions shared as part of the responses to the question.

All the feedback gathered during the Community Conversations was documented and reviewed by city staff with the assistance of the Cardinal Health staff. Responses were organized to summarize the “pains” and “wants” of older adult participants and the “worries” and “wants” of caregiver participants. These pains, worries and wants were organized under several categories, including transportation, housing, social services, health/wellness and purposeful living. This approach helped to define the problems being faced by residents, empathize with their feelings, and begin formulating possible solutions to test.

What emerged from the feedback as a top priority was navigational services. Numerous comments revolved around finding and understanding services. This included everything from understanding how to fill out Medicaid paperwork to finding someone to help with home maintenance. Numerous resident and caregiver comments led back to needing resources, both on-line and in-person, to answer questions about where to find something or how to understand something. While this wasn’t the only need identified, it rose to the top as an urgent problem and one that could be solved.

These Community Conversations were taken back to the agency summit participants in a second in-person meeting to share the results and to determine which organizations were interested in partnering on next steps. The community results aligned closely with the agency results, confirming an understanding of their clients’ challenges and needs. Several participants expressed an interest in being involved as the city moved forward with implementing solutions. Syntero, Dublin’s non-profit behavioral health agency, which was already working closely with a subset of older adult residents, soon became the lead agency to partner with the city on piloting a resource center for older adult services.

Starting in February 2019, with financial assistance from the City of Dublin to hire two part-time navigators, Syntero began meeting with older adults and caregivers on Fridays and Saturdays. As needs of residents using this service are better understood during the first few months of operation, other agencies will be brought on board to provide information, education and services to meet those needs. This two-day a week pilot will allow us to gather further information from residents regarding needs and level of satisfaction with the Navigator services. From this additional feedback, we will be able to adapt the program over time to better serve the needs and wants of our residents.

Along with the in-person navigation services, Syntero, Ohio University and the City of Dublin are also in the process of developing a website to organize information, educational opportunities and services into one on-line resource. To brand the overall program and develop this website, older adult residents were invited to an initial brainstorming session. As branding ideas and website prototypes are developed, residents will continue to be involved, offering their perspective and ideas.

Feedback and next steps have been shared with all residents who attended a Community Conversation session. The city will continue to keep this group and other residents updated and involved as we work to test and adapt service delivery needs.

Building Capacity for Further Resident-Centered Engagement

The Aging-in-Place project was a first attempt by the city to use human-centered design methods. As we look to expand these types of processes to other service delivery improvements, we are beginning to build additional skills among members of our existing process improvement and innovation team. Consisting of nine certified Black Belts, this team is trained in lean and process improvement techniques and has been leading process improvement projects for close to two years. The team was rebranded in 2018 as PIEworks to denote their three areas of focus, with the “P” representing process improvement, the “I” representing innovation, and the “E” representing engagement. Efforts are now underway to provide training and development related to innovation skills, including design thinking, and engagement skills, including facilitation. As these are further developed, the team will be ready and available to work units that wish to use this resource to assist with resident-centered service improvement processes.

Design Thinking in Hennepin County, Minnesota

In December 2016, Hennepin County began an initiative it branded as Innovation by Design, incorporating human-centered design concepts, lean processes, facilitation methods and the County’s core values into their own framework for resident-centered problem solving. Housed within the Hennepin County Center of Innovation and Excellence, a dedicated, trained team of 15 employees was put in place to assist work units throughout the organization as they look to solve service design and service delivery challenges. County divisions bring forward design challenges and work with the center’s team members to create solutions using Innovation by Design methods.

The county describes Innovation by Design in the following way:

“Innovation by Design is a Hennepin County creative problem-solving approach based in human-centered design and design-thinking principles. It starts with the people you’re serving and ends with a service that is specifically tested and designed for them.”

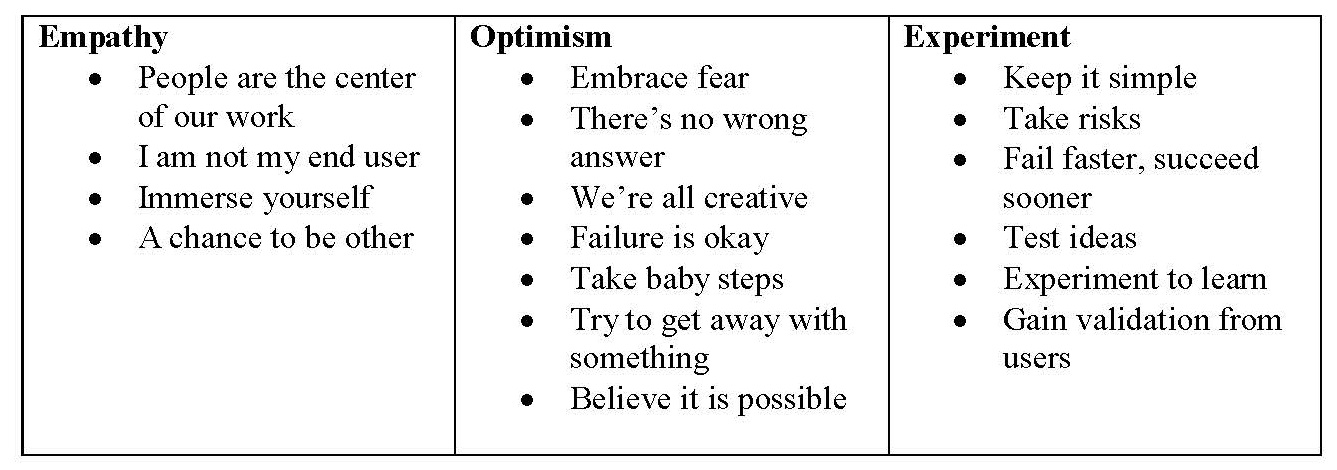

Two of the Center’s Design Managers, Amy Schrempp and Rachel Walch, recently led an Alliance for Innovation webinar explaining the Center’s approach and accomplishments. During this session they shared that the approach is grounded in the mindsets of empathy, optimism and experiment, further describing each of these as follows:

Empathy is put into practice by identifying the needs of the end-users through various forms of direct engagement, such as interviews, focus groups and/or observation, as well as directly involving end-users in the design process steps. A design-thinking technique called empathy mapping is used by the county team to gain greater insights of end-user needs. This technique involves close listening and observation of the end-users to map what they say, think, do and feel as it relates to the service or product being developed. Let’s take for example the redesign of a website. The end-user might say “I don’t understand what to do here,” while what he or she might think is “this is frustrating.” What he or she might do is leave the page and look for another way to accomplish the same task. Ultimately what he/she might feel is frustration. This information can help gather a fuller picture of the user experience.

Optimism takes what is learned during the empathy stage, closely examining the information and data to find themes, service gaps and ideas for improvement. Brainstorming occurs in this phase, bringing in a diverse group, including those involved with the service delivery and the end-users. Together they ideate a variety of creative ways to solve the problem or improve the service.

Experiment begins with prototyping ideas generated during the brainstorming process. A prototype could be a mock-up design, a storyboard, a process map, or any other similar product that allows an idea to be tested. This phase allows for experimentation and iteration of prototypes until the group reaches a point in which there is a viable solution to implement. Even then, an implemented solution from this phase would be observed and adjusted as needed. A key to success in this phase is the assumption that failures will take place, and these failures will result in design changes and ultimately in a better product.

Hennepin County Practices in Action: Young Adult Housing Model

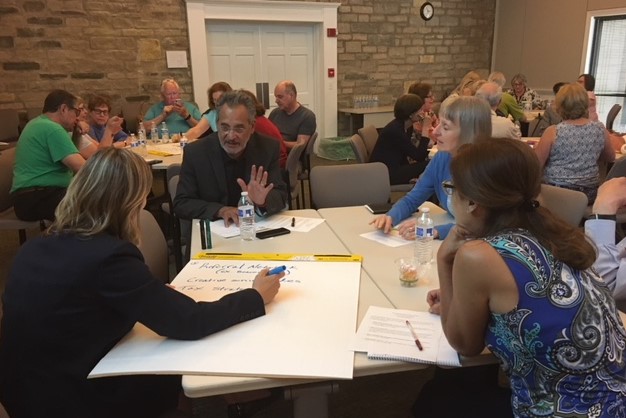

A recent example of Hennepin County’s Innovation by Design in action was the examination of transitional housing and support services for young adults who were soon aging out of foster care. This case study was shared during the webinar and as part of a recent Transforming Local Government conference session. The challenge before them was to discover what this group of young adults most needed to succeed as they moved from foster care into independent living and how to best provide those services. To fully understand the needs of this resident base, the county’s design team worked with a group of young adults that had been part of the foster care system as well as with community-based social service and governmental organizations that provide services to the end-users.

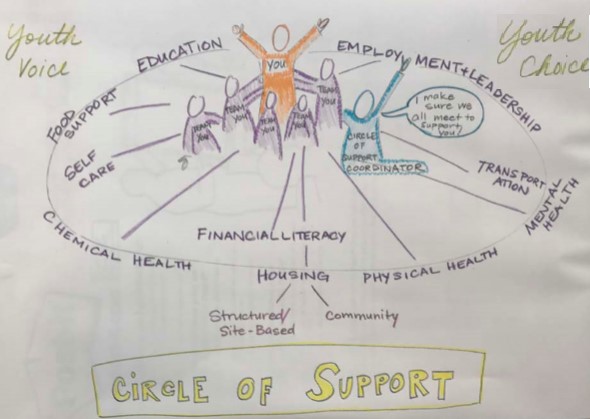

The design team first worked with the young adults to walk them through visual activities where they mapped what they felt they could manage on their own versus what they thought they needed help with. One activity had the young adults draw out what their living space might look like and what support and services they might need in the space or to be able to successfully remain in the living space. Identified needs ranged from food and clothing allowances to a fitness center to emotional support groups. Next the design team brought the young adults together with the social service and government agencies so that collaboratively they could better understand needs and begin generating creative approaches to delivering the identified needs. The design product that emerged was a visual “circle of support” that identified the continuum of support needs. The circle of support drove home the need for coordination among the agencies and for a coordination point.

This drawing was used by the design team to prototype the model developed during brainstorming.

Outcomes of this process included a better understanding of individual needs of the end-users, an understanding of how the services could be better coordinated and improved communication and collaboration among the involved agencies. The young adults felt heard, involved in improving their futures and more trusting of the government and social service agencies that provide services to them. The most significant outcome of this project was the realization that a single point of coordination was needed to assist the young adults in accessing support services from the various agencies and organizations. This service has now been funded and will soon be implemented.

In my conversations with Amy Schrempp, she noted that this and other similar Innovation by Design processes are successful due in great part to the involvement of the end-users. However, she also stated that it is important to incorporate available data resources that can provide further resident insights. Data can tell part of the story of the larger community base and provide guidance during the design-thinking process. Typical design-thinking models and tools, she added, are geared toward product development in the private sector, not service delivery. Hennepin County’s Innovation by Design adapts these models and tools to better fit public sector problem-solving related to improving services.

Implementing Resident-Centered Design

So how do more local governments begin to use these concepts? Success will require two primary areas of focus. The first will be a change in mindset and culture, and the second will be an emphasis on skill development and implementation.

How do we change the mindset and culture of our profession and organizations to embrace resident-centered design?

- Branding – Let’s start by branding it as “resident-centered design” and owning it as ours. Resident-centered design needs to become part of what local governments consider a best practice in resident engagement. Customized tools and training are needed to allow us to easily incorporate it into our organizations. Similar to Hennepin County, we need to adapt the methods and promote them to meet our public-sector needs.

- Tell the Stories – The stories of successful implementation, like those provided here, need to be told more widely by our professional organizations. The Alliance for Innovation, through conferences, webinars and articles, has been on the leading edge advocating for human-centered design among local government professionals. Bloomberg Philanthropies used the techniques to advance ideas among the 35 Champion Cities that were recognized as part of the 2018 Mayors Challenge. More need to follow in the footsteps of these two organizations.

- Fail Fast, Fail Forward – Next, let’s embrace the process of not getting everything perfect the first time. Instead let’s develop in our organizations a shared understanding that we can make the product more perfect for our community because we have chosen to involve a diverse group of residents in the design process. Iterating, prototyping and testing can become integral to how we design services and, as part of that, we accept that failure is part of the process and part of the ultimate success.

- Start with an Easy Win – Begin with a service delivery problem you know has been a pain point for residents but one that has internal champions that will want to invest the time and effort in solving the issue and improving the service or product. A first win can be a catalyst for others to jump on board and for the culture and mindset within the organization to begin changing.

- Comfort with Residents in the Room – As local government professionals, we are trained to develop solutions to problems for those we serve. Involving residents in a collaborative and iterative process of problem-solving can feel uncomfortable. The steps of brainstorming, prototyping and experimenting can seem messy and one we may want to have residents see or experience. This mindset will change only as more employees have the opportunity to be part of a resident-centered design process and see the results firsthand.

How do we begin building skills and implementing the concepts?

- Small Team of Champions – Regardless of the size of your organization, begin with a small team of employees who are eager to be a part of improving services. Focus on building their design thinking, process improvement and facilitation skills and help them find initial projects to test and grow their abilities.

- Invest in Skill Development – Set aside appropriate funding and bring in outside experts to train your team. Consider a professional service contract with a consultant that can develop and coach the team through the first few design processes. Once skills are well developed internally, employees can begin training each other.

- Learn from Others – There are counties and cities that are getting resident-centered design right. Your team can remotely, through on-line meetings, or in person, through site-visits, connect with and learn from other local governments. We are fortunate to be part of a profession that is eager to share and learn from each other. Take advantage of the knowledge and experience of colleagues.

- Celebrate Wins and Losses – Building strong resident-centered design skills will require that we celebrate and learn from both our successes and failures. Team members will be more eager to talk about and learn from failures when they realize it’s part of the process and accepted by the organization.

- Market the Team – Once the team members are proficient and have had a few successes, begin promoting their availability. Get the members out into the organization to talk about their results and offer their services to others. Let the requests for assistance be voluntary so that work units know that they will not be forced into a process but can ask for it if they determine if would be helpful.

Adding resident-centered design methods to our toolbox of community engagement options will help us as local government professionals to improve the quality of services, design new services and build stronger relationships with our residents. While not the only tool we should use, consideration should be given to its potential success as we continue to pursue ways to best collaborate with our residents.

Michelle Crandall is Assistant City Manager in Dublin, Ohio and a Richard S. Childs Fellow.