By Noorya Hayat

With the midterm elections just a few months away, voter engagement and GOTV efforts will soon reach a frenzied pace. The news media will be abuzz with articles on how voters are feeling, and poll and after poll will follow their opinions. But these initiatives and attention, which tend to focus on past or “likely” voters, also tend to neglect one critical part of the electorate: young people, who are then often blamed for not turning out to vote at high rates. That vicious circle of inattention and condemnation must be disrupted and replaced with a more sustainable framework for preparing youth to participate in democracy—a model to “grow voters” in which schools must play an integral role.

The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) is a nonpartisan, research-based think tank based at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life that has studied the civic and political engagement of young people, ages 18-29, for the past two decades. In the last two national elections (2018 and 2020) our research documented major increases in youth voter turnout. But young people still vote at a lower rate than older adults, and inequities by race/ethnicity, education, and other demographic and socioeconomic factors continue to plague youth voting. Our research has consistently shown that it is not an issue of youth apathy, but of whether young people have adequate and equal access to civic learning and engagement opportunities.

For example, a CIRCLE survey of teens (ages 14-17) found that a majority wanted to take a course on U.S. politics and government, but a third of those who were interested didn’t have access to such a class in their school. We found that 1 in 6 youth weren’t learning about elections and voting in school or in their personal networks. And we found that, across multiple measures of access to civic learning, young people in rural areas, youth from historically marginalized communities, and other underserved young people were even less likely to have access to electoral learning and engagement opportunities.

We cannot expect young people to turn 18, be handed a voter registration form, and automatically become informed, engaged, and motivated voters. Civic attitudes and electoral processes must be learned—not just the how, but the why of our democracy, which is only strong and sustainable when all people are educated and empowered to participate. CIRCLE’s research has found that our communities and institutions are not equitably providing that civic education and empowerment to all youth. Those gaps and inequities in opportunity are in turn reflected in lower and unequal participation at the ballot box.

In our newly released CIRCLE Growing Voters report, we outline a paradigm-shifting framework to fundamentally address these issues of inequitable access and support for young people. We call on institutions to adopt a holistic approach and develop community ecosystems that support their civic development. These ecosystems must provide young people with three essential elements:

- Access and exposure to civic learning opportunities;

- Support for all youth to be able to find, enjoy, and take advantage of those opportunities; and a

- Culture that gives those opportunities meaning by valuing young people’s participation as voters and leaders.

The CIRCLE Growing Voters report and framework includes findings and recommendations for nearly a dozen stakeholders who must work together to create these ecosystems of support for youth. Among these stakeholders, K-12 schools have a critical role: they not only provide formal civic education in the classroom, they also connect young people and their families to community resources and infrastructure. Moreover, schools have the civic imperative of preparing the next generation of informed and engaged citizens.

We know this work isn’t easy. CIRCLE’s 20 years of research on civic education has underscored how overwhelmed teachers and administrators can feel, and how difficult it is to balance competing demands and educational goals. During an election year, it can feel even more difficult to talk about voting and political issues that may seem too contentious in a hyperpolarized environment. But students are already talking about these issues, they are bringing their lived experiences into the classroom, and they realize that the outcome of elections will affect their daily lives—even if they’re not yet eligible to vote or don’t know how to participate. Schools can and must help youth learn about democratic processes and about how they can make their voices heard at the ballot box and beyond. And they can do so in a nonpartisan way.

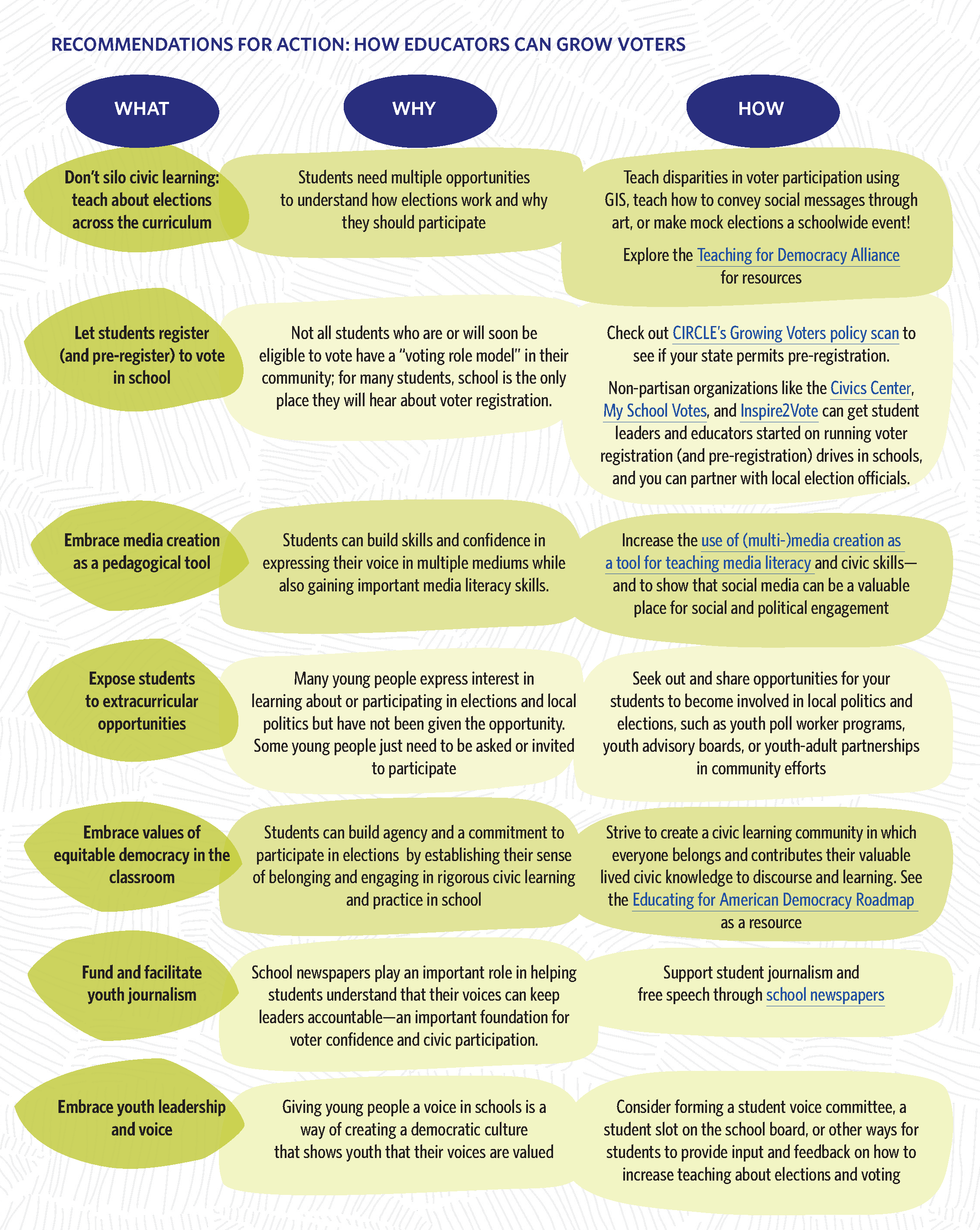

How can schools help grow voters? Our framework makes the case for what educators can do and why it’s so important:

When should we teach about elections and voting?

One of the major tenets of growing voters is that it must start early—long before youths turn 18. That includes in schools: in elementary grades, educators can teach about “everyday civics” and foster a democratic school environment that helps youths develop their views and voices and promotes participation in decision-making. In middle school and high school that culture of participation and leadership can be reflected in more formal structures such as student governance and mock elections. This isn’t just about getting students to register and vote, but about deeper civic development that is scaffolded, inclusive, and creates multiple pathways to learning and engagement that meet young people where they are at.

What should we teach?

Many states have revised and updated their social studies standards to include what high-quality civics education looks like. It’s more than just U.S. history and government: it includes best practice pedagogies such as discussions of social issues, how democratic processes work, how to take informed action so youth can address issues they care about, and news media literacy. These elements of civic learning create a solid foundation to teach about elections and voting.

One valuable resource is the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap (EAD), a cross-ideological initiative launched last year to reanimate civics and history education. EAD was developed with input from more than 300 stakeholders, including educators at every grade level, practitioners, scholars, and researchers who distilled their expertise to craft a vision for compelling, rigorous, and honest civic education. It is not a curriculum but a set of guides that educators and administrators can adapt to fit their needs, with accompanying pedagogical companions and other resources to help facilitate implementation. CIRCLE also spearheads the Teaching for Democracy Alliance, which brings together 18 nonpartisan organizations that provide resources and expertise on how to strengthen student learning about elections and voting.

Who should be involved in growing voters and teaching about elections?

Civic learning shouldn’t be confined to civics class. Young people should be learning about elections and democracy across the curricula, so that students have opportunities to absorb information in multiple settings and solidify their identity as voters.

More broadly, the CIRCLE Growing Voters report calls on all communities and institutions to work together on preparing young people for electoral participation. Schools should be a central node in these ecosystems that must also include community organizations, parents and families, and young people themselves. Through formal or informal partnerships, schools can collaborate with elections offices on voter registration or opportunities for youth to serve as poll workers; with grassroots organizations working on issues their students care about; or with local libraries and museums who can offer civic education experiences outside of the classroom. In a nutshell: teaching about voting and elections shouldn’t just be a lecture for a high school classroom but a cornerstone of the educational experience that brings together the whole community to support young people.

What should we do next?

The CIRCLE Growing Voters report has a guide for communities and institutions to map their existing assets, capacities, and relationships that can support this work. We encourage educators to use this tool to kickstart conversations about how their school can adopt, expand, or strengthen a CIRCLE Growing Voters approach to civic learning. Remember also that this work shouldn’t be done for young people, but with them. Speak to students about what they want and need to learn about elections and voting and always seek to partner with them. For additional specific recommendations, check out the table below:

Noorya Hayat is a senior researcher at CIRCLE.