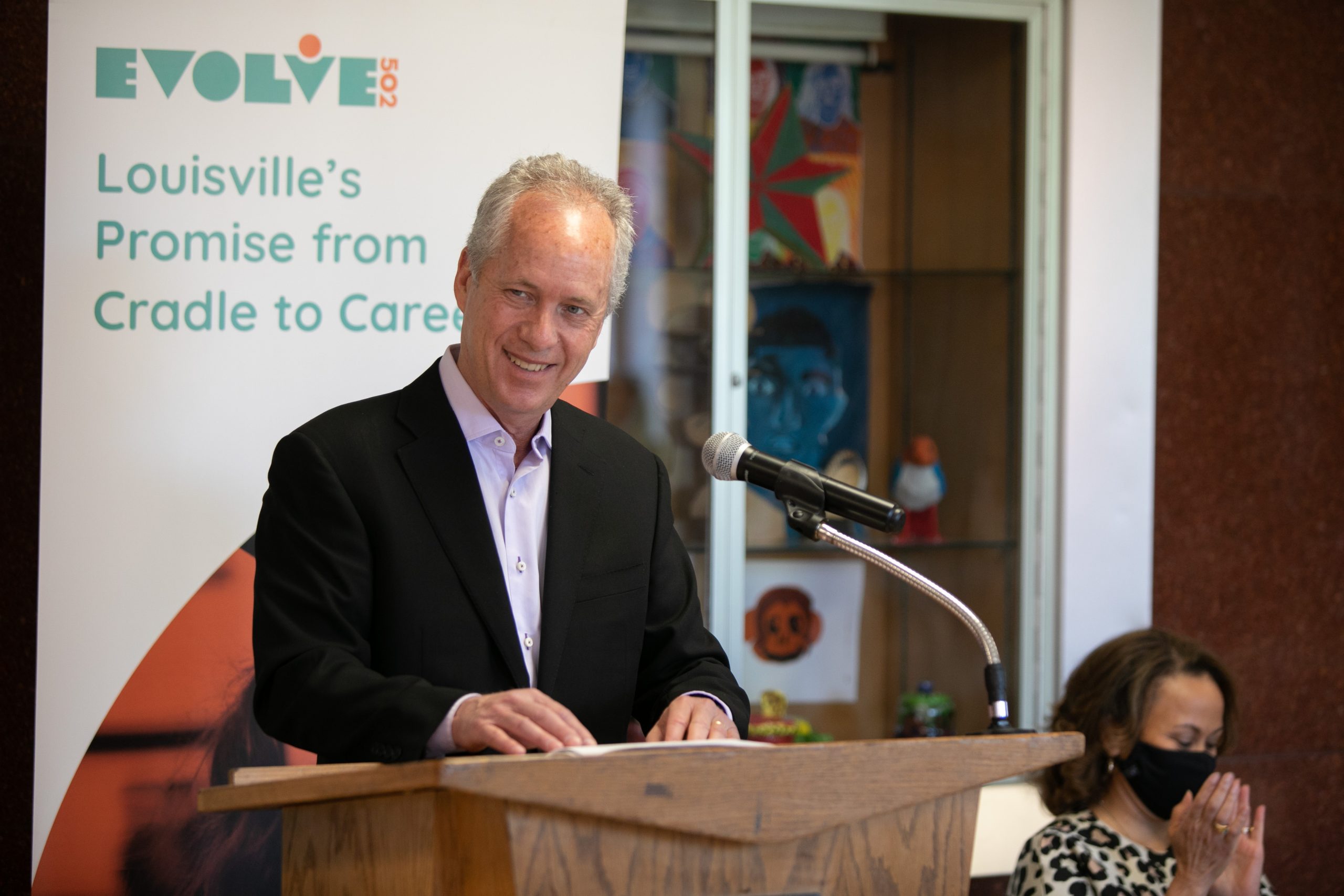

Greg Fischer served as the mayor of the consolidated city and county of Louisville, Kentucky (Louisville Metro), from 2011 to 2023. In 2013, Governing magazine named him as one of its “public officials” of the year, an award it has given out since 1994 for outstanding public accomplishments. A former businessperson and inventor, Fischer ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in 2008. Two years later he was elected mayor. Assuming office at the tail end of the Great Recession, Fischer focused on economic development, using data to drive metro performance, and embracing the idea that government should be “compassionate.”

Greg Fischer served as the mayor of the consolidated city and county of Louisville, Kentucky (Louisville Metro), from 2011 to 2023. In 2013, Governing magazine named him as one of its “public officials” of the year, an award it has given out since 1994 for outstanding public accomplishments. A former businessperson and inventor, Fischer ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in 2008. Two years later he was elected mayor. Assuming office at the tail end of the Great Recession, Fischer focused on economic development, using data to drive metro performance, and embracing the idea that government should be “compassionate.”

Fischer’s three terms were notable for Louisville’s success in attracting jobs and launching innovative initiatives to promote higher education opportunities and provide affordable housing for residents. But his tenure was also punctuated by tragedy and hardship with the onslaught of the COVID pandemic and the shooting of Breonna Taylor by an undercover narcotics detective.

Mike McGrath, Director of Research and Publications at the League, interviewed Fischer in November of 2023.

Question: You were a successful businessman before you were mayor of Louisville. What made you want to be the mayor?

Answer: What I enjoyed about my business career was having the opportunity to lead companies where the business served as a platform for people to grow and realize their dreams – their human potential. Through that process, we became best in the various industries in which we competed in. Once my major business was sold, I thought a worthwhile way to further scale the effort to build human potential would be by serving in government, where there’s the opportunity to reach a broader, more diverse population with a lot of resources making it possible to deliver more positive outcomes for more people. That was my passion and philosophical reason behind running for mayor.

And, from my business experience, I felt I had the executive skills that a mayor needs in a city like Louisville, with a “strong mayor” form of government and a billion-dollar budget and about 5,000 employees.

Question: You hoped you could make a difference and help people flourish. Do you think you have been able to do that?

Answer: Yes. You don’t change the world overnight in any political position, but you look at areas where you think there’s opportunities for improvement and then you start developing plans to make it happen. Local government is a service business and on the improvement side, even with severe budget constraints due to state mandated pension changes, our stat system showed we delivered ever-improving results with 1,000 fewer employees over my twelve years in office. On the innovation side, we created a number of new initiatives. One I am particularly proud of – is Evolve502, a promise scholarship and out- of- school- time support service for youth.

Along with city government dollars, we raised enough money from the private and philanthropic sector to ensure that there’s no financial barriers for a public high school graduate in Louisville to get a credential or college degree, whether at our community college, Jefferson Community and Technical College, the University of Louisville, or Simmons College of Kentucky, the HBCU here in town. Data shows that the root cause of most problems that come through a mayor’s office is poverty. Disrupting poverty through programs like Evolve502 is good for residents and good for business. So, when you ask, “did you make a difference,” there’ll be tens of thousands of people who are impacted by moving out of generational poverty because of a program like Evolve502.

Question: When you came in as mayor, did you have a particular set of policy strategies that you wanted to try, or were you just going in to see what you found and then develop them?

Answer: When I started, we now know that we were at the tail end of the Great Recession. Our major focus was on business development and job growth. I’m an entrepreneur so I had a lot of real-life experience in those areas. We were fortunate in being one of the early cities to regain the jobs that were lost in the Great Recession. I spent the early days of my administration in 2011 developing and communicating the values that would run our organization, building a team, and then creating a 100-day plan so that we could put all that together.

We used data to identify what our priorities would be. I announced three big values in my inaugural address that would guide our decisions. One was for Louisville to be a city of lifelong learning. Any city that’s got a lot going on has lots of people who are curious, they’re entrepreneurs, they’re enthused by education. Second was to become a healthier city – physical, mental, environmental, and spiritual health.

The third was the concept of becoming a more compassionate city, which got people’s attention because they weren’t used to hearing language around compassion and interdependence from a government leader. It became a value and a practice that was integrated in everything we did. If you came to Louisville and started talking about compassion, people wouldn’t look at you funny. They would know that we socialized that norm through not just speaking, but also through action.

In my twelve years as mayor, my experience taught me that a good mayor combines the head of a CEO with the heart of a social worker.

Question: How do you characterize that? What kinds of concrete things could be done to make a city more compassionate?

Answer: When you think about it, government is in the compassion business. The way we define compassion is respect for every citizen so that their full human potential is shining, and their dreams are coming true. They’re able to move forward somehow, either through the availability of programs, learning, work, or whatever it might be. Compassion is an action word.

The program I just described, Evolve502, was just that – good public policy and compassion – both! When you look at areas like higher education or more affordable housing, it’s both. Or baby care, pre-birth, and post-birth. That’s both as well. Government allocates resources to common needs like roads, clean water, and parks. It also tends to allocate resources to people who don’t have as much as other people, to try to get them to a higher standard of living.

You can go through almost every policy and make a compassion argument for it. Certainly, that was the case during the pandemic. We used data and compassion to drive where our testing and our vaccination events would take place. We were one of the early users, if not the earliest user, of wastewater detection for the virus. That approach ensured that we were targeting the most impacted neighborhoods. We knew that people of color typically had a higher infection rate and a higher mortality rate from COVID. We were one of the few cities that reversed that pattern, and I think a big part of it was our use of data, which some people would say is hard science or business oriented. We were using those tools in a way that lifted up people who traditionally have not been lifted up – a common sense and compassionate approach.

Question: When you talk about using data to drive policy, what do you mean?

Answer: There’s a couple of ways to look at that. One is, whenever we had a problem, I would ask two questions: What is the data telling us about that problem and what’s the impact on our residents? If you can answer those two questions, you’re off to a good start in terms of solving problems. There are a lot of ways to solve problems. Sometimes people rely on gut or instinct. There is a place for that, but it is always best to make data-informed decisions.

Continuous improvement is core to using data efficiently, with a problem-solving approach that’s defined and repeatable, like a “plan, do, check, act” process baked into the daily work of the administration. The best practice, whether it’s in the private sector or the public sector, links a robust strategic planning process built to the needs of residents, with performance/data gaps driving your goals, actions, improvements, and innovations.

Beyond quantitative data, government is also full of qualitative data. By that I mean language – all kinds of language – suggestions, complaints, conversations. How you process that language data and combine that with quantitative tools to get the biggest return on investment is a necessary skill. The bottom line is that a data culture needs to be infused throughout your organization so that decisions are data-informed, whether it’s quantitative or qualitative data.

Question: You would do an analysis of all your programs and all your departments and try to apply data to those as part of a broader strategic planning process? Did you also use compassion in that same way? Did you try to find out if compassion was infused in all your programs and policies?

Answer: Yes. Again, I think government is in the business of compassion or equity. You hear the term equity used a lot more these days; it’s not that different from compassion. Actions to achieve compassionate results – equitable results – are part of how you analyze everything. We had a formal equity analysis for our resource allocation.

And, through acts of compassion where you mobilize the community, you build what I call social muscle – relationships and the feeling of interdependence amongst your residents. You will need that social muscle when tragedy strikes your city, and tragedy is going to strike every city sooner or later. It could be a mass shooting, it could be a tragedy like the Breonna Taylor killing in Louisville, it could be a major natural disaster. The question is, how does a community and its people respond when tragedy takes place?

Do they turn on each other? Do they help each other? Let’s say a mosque is defaced and that action is condemned by the community, and we call for some volunteers to come out and help clean up the mosque and 1,000 people showed up to do a job that required two people. That’s what I call building, and using, the social muscle that’s required in this day.

Question: Is that a real example?

Answer: Yes.

Question: Going back to the beginning of your mayorship, you put a big focus on economic development, and it seems like the city at least was successful in doing that. What do you attribute that success to when compared to other cities of similar size?

Answer: It’s a combination of attracting and retaining jobs. We did a lot of workforce development. One of our early projects was working with the Brookings Institution and Jim Gray, the mayor of Lexington, a city which is just an hour down the road.

I went to (Brookings) right after I was elected to ask if they could help with my administration’s first strategic plan. They weren’t providing that service anymore, but they were building out a concept on metro economies and how metro economies are the engine of the world’s economy. Lexington and Louisville had been traditional rivals, which I thought was just really silly. Here we are a city of 800,000, they’re a city of 300,000. Compared to the competition that we have globally, we should be working together, not against each other. We decided to focus together on workforce development and exports from small- and medium-sized businesses. It was a project where we met our five-year export goals in three years.

Question: Were you focusing strategically on particular industries?

Answer: Yes, we focused on five areas of economic development where we felt like we were either the best in the world or could be the best in the world. We’re a Midwestern, upper South economy with numerous legacy industries, along with some new industries. In Louisville, our economic development pillars are advanced manufacturing, wellness and aging innovation, logistics – UPS has its global hub here – food and beverage, and business services. It is important to understand your city’s value proposition and relentlessly develop those areas.

We also created a new concept called “bourbonism” around bourbon tourism, which has injected massive amounts of life and capital into our hospitality segment – new hotels, and new experiences. Kentucky is home to 95% of the world’s bourbon production so this was a natural value proposition for us. As Napa (California) is to wine, we’ve got people flooding into our city for bourbon tourism. It’s been a lot of fun.

Question: Louisville, while you were mayor – and all cities really – were experiencing some tough times with COVID and then with the police violence problem, the reaction to it, and the polarization around that issue. I imagine that the Breonna Taylor shooting created a tremendous amount of polarization within the community. How did your city respond to that, both in terms of trying to come up with some solution for the policing issues and also how to deal with the differences of opinion on that issue?

Answer: That was an extraordinarily difficult time. COVID was taking place and then the George Floyd murder was seen around the world, and then Breonna Taylor’s killing began getting national and global attention. It was a terrible tragedy that inflamed our city and the country.

It was a super emotional time, battling the scourge of COVID and managing all the protest- related issues and the obvious need for police reform. I am thankful for the many skills that my experienced team brought to this challenge and the way the protest community and our police were eventually able to work their way through this unprecedented time.

People were rightfully upset. People process emotions in very different ways and on their own timeline. That period presented countless unique challenges for leading and managing. You ask if it was a polarizing time? I would literally have back-to-back meetings where one group would come in with a demand to defund the police department and the next group would come in with a demand to go into the center of a protest and beat people with billy clubs, saying the protestors would disperse and the demonstrations would be over. Normally challenges have a clear outcome that the vast majority of people rally around. The racial justice protests did not present that clarity to the community and the country.

The job of the mayor in a situation like this is to say, “What are we trying to achieve, what are the goals?” Ours were to keep the city as safe as possible and allow the First Amendment right of free speech during unprecedented challenges. Then we also must find the truth. Then justice needs to prevail. People want things to happen quickly under highly emotional circumstances like the protests. Due process does not work that way.

I was the president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors at the time as well, so that was another responsibility. Donald Trump was vilifying many cities and mayors as they struggled to protect their cities from the more destructive protest elements. Part of my job was to push back on President Trump and offer a different narrative on the challenge of ensuring First Amendment rights while protecting people and property.

There was a lot going on. In Louisville, we had over 100 continuous nights of protests…some people said, “How can we call ourselves a compassionate city and have a tragedy like Breonna Taylor’s take place?”

Admittedly, I was ashamed and embarrassed by that question. Then I looked at it in a different way to say, “Wow, we’ve really embedded this notion of compassion in our city where people aspire to a higher value like that, and they’re holding us accountable.” I was inspired by that in a way, and my team reinforced our commitment to seek truth and justice and not get distracted by people on the extremes who wanted something immediate. During this it was important to keep top of mind the suffering of the families of Breonna Taylor and two others who lost their lives in protest related activity, David McAtee and Tyler Gerth.

When you have a once-in-a-century pandemic and twice-in-a-century racial justice demonstrations – at the same time – it’s going to be difficult. It’s meant to upset the status quo because the status quo is not working for everybody.

Comparatively speaking we did okay compared to the other three cities that also endured long periods of protest. Five hundred buildings were burned down in Minneapolis. We didn’t have any buildings burned down. Seattle and Portland had all kinds of chaos. As difficult as it was, I think the fact that we had worked in the area of compassion, and almost all the protest leaders and I knew each other (except the ones from out of town), we were able to work through it, recognize the difficulty of it, and ultimately get to truth and accountability.

There was one area where I could – and did – move quickly to resolve one part of the challenge in that time. My administration controlled the civil settlement with Breonna Taylor’s family. Tamika Palmer, Breonna’s mom, was an amazing source of community and national strength throughout all this. She was a grieving mother and dialysis technician who suddenly was put in the global spotlight, and everybody’s tugging on her each and every way. The city had a choice. We could either fight a civil settlement, string it out for years, or make a settlement quickly to alleviate that source of the family’s pain and move our city forward. I moved very quickly to do that.

We were 10 years into our compassionate city work by then. It was my third and final term, and we had the community relationships and the governing experience, but 2020 was by far the most difficult time of my 12 years as mayor.

Policing in America is at a real inflection point. It’s not working the way it should. That really came to the fore in 2020 all over the country, and certainly in Louisville. Ours is a case study. Law enforcement all over the nation saw what happened to the police officers in Minneapolis involved in the George Floyd murder. They’re thinking, “Well, one of the best ways to avoid this is to pull back on our engagement with residents.” That combined with all the COVID shutdowns led to an increase in violent crime in cities all over the nation.

Police officers are asked to take on too much – crime prevention, homelessness, domestic violence and so on. Police emotions were understandably high as well in 2020. Some in the police department would say, “Mayor, you’re either with us or you’re not.” This binary thing, the so-called thin blue line of policing, is a real problem. The thin blue line should be a unifying community thread as opposed to the us versus them mentality. Some of the more strident police unions are way out of bounds in terms of how they reinforce the thin blue line concept.

A national reckoning with policing is way overdue. There are roughly 18,000 police departments in the country. There’s not a uniform method where the fundamentals are established from the ground up and from the federal government down. When I say ground up, I mean from the community level. Ultimately, the community should be viewed as a police department’s greatest asset. Community and police working deeply together should be the goal. That’s largely not the case in America right now.

There should be a minimum set of holistic public safety standards that’s resourced both from the police department side and the community side. It’s not either/or. It’s working together. We all own public safety. Right now, people want to look at the police department as the owner of public safety. That’s a very simple way to look at it because policing is primarily the law enforcement aspect of public safety. Community mobilization, violence prevention and intervention, re-entry, the justice systems, and corrections all need to be redesigned in a holistic, healthy system. At the end, when a tragedy takes place in a city, instead of blaming, society should say, “What happened? Where did the entire community/police system fail? And how are we going to fix and improve this together?”

Question: Policing reform is one area that you’re interested in. Are there any other areas of reform that stand out?

Answer: Yes. I’m on the board of Cities United. Its focus is to reduce gun violence among young Black men and boys. To me, this work is a fight for the soul of our country, a test for our nation if we truly care about every life lost. Why does our nation have so many gun violence issues? It’s pretty simple. To start with, we’ve got more guns on the streets of America than we have people. We’re an extreme outlier compared to the rest of the world. Combining that with the extreme gap in income and wealth for a country as rich as we are, not just total GDP, but per capita as well, is a deadly mix.

We need to figure out ways to address these two areas. I’m more optimistic about the reality of addressing the wealth and income gap than the gun issue because of the polarity around Second Amendment issues. When you look at countries that we compete with, they have a much more balanced economic system in terms of wealth, income, pensions, and skill development than we have. America, in my view, is way too laissez-faire in terms of how people end up in the economic situations they are in. Fighting poverty makes moral, economic, and public safety sense.

There need to be minimum levels for skill development, housing, healthcare, education, and other fundamentals. The goal is to mitigate poverty as much as you can. This is doable. Some European countries, also, Australia, New Zealand, have income and wealth gaps much smaller than ours. There are countries where there’s no homelessness, and to get back to what you talked about earlier, there’s far less per capita violence than in America. Fewer guns per capita are one of the issues behind that, but it’s also because people’s basic needs around housing, food, healthcare, education, and workforce skills that provide a family supporting wage are much more effectively resourced than in America.

I wish we could send the whole country on a field trip so Americans could see countries without deep poverty and gun violence, to understand that the challenging aspects of what we’re living with here in our country does not have to be that way.

Developing systems that produce societal results is how we define our responsibilities to each other through government. Obviously, redesigned organizations, new policies, and reconfigured resources are a big part of achieving better results from a new cultural approach. The point is that the systems that we have in place produce the results that we are unhappy with. To get better results, systems must change, and the political maturity must be in place to make it happen.

Question: Sounds like you’re calling for a reverse de Tocqueville visit.

Answer: Many of America’s challenges are multi-generational, baked in, in some respects. What the country is doing right now with our big systems of education, workforce development, healthcare, housing, etc… is not working, So, to keep doing the same thing over and over doesn’t make a lot of sense. The political flexibility, the nimbleness that we have at the federal government level, and the way we elect people, is not suitable for the challenges that we’re facing right now.

Question: Well, that’s a whole other ball of wax when it comes to reform, the electoral system. That can’t be done on the local level as much…

Answer: It can be done by who we vote into office. When people start voting on the gun issue or on the poverty issue, then change will happen. What I’d say, ultimately, to people is that if you’re upset, change the system through the ballot box. Now, alarmingly over the last six years, the right to vote is being made more difficult. We want to make sure we don’t end up like the boiling frog analogy, that our democracy is being attacked gradually in all these different ways and people just become immune to it, and then one day our democracy is gone. This is a very dangerous time.

Question: Well, a lot of people are talking about a crisis of democracy. Then we focus on local government. It seems like the national crisis is a big problem right now that institutions that used to be respected by both sides Republicans and Democrats are no longer respected. There’s a tremendous amount of public distrust for public institutions. What are some positive signs you see about how this crisis of democracy might be averted?

Answer: I think a lot of the solution is at the local level. Polling always shows that trust in government is highest at the local level. Building that trust is one of the jobs of the mayors of America. We’re the elected officials on the front line. The essential workers of American politics are the mayors because you can’t hide from our customers – our residents. You’ve got to act, improve, innovate – get results. You’ve got to show that institutions work, and you’ve got to show that you can bring people together, so they realize we’re really not that different from each other.

Leaders have an active role in doing that, whether they’re government leaders or private sector leaders. You do that through programs that work. The Evolve502 education program that I talked about, new and affordable housing, all kinds of opportunities exist.

When government works at the local level, trust is built. You’ve got to combine great policy with results and empathy and love for your people, love for your country, love for your city. It’s a very achievable task. It’s the minimum that a mayor needs to deliver for the people.

Question: That’s a great way to end that conversation. Thanks for the interview. I really appreciate it.