By Chris Green

One of the most famous stories from World War I is the tale of the Christmas Truce in December 1914. British and German soldiers in Belgium, who normally shot at each other on the front lines, spontaneously emerged from the trenches. They retrieved and buried the dead that had been unreachable during the fighting. They then sang carols, exchanged gifts and even played soccer.

It was a surreal moment of peace amid the massive carnage of the Great War, which caused nearly 10 million military deaths and left another 10 million civilians dead. An additional 21 million were wounded.

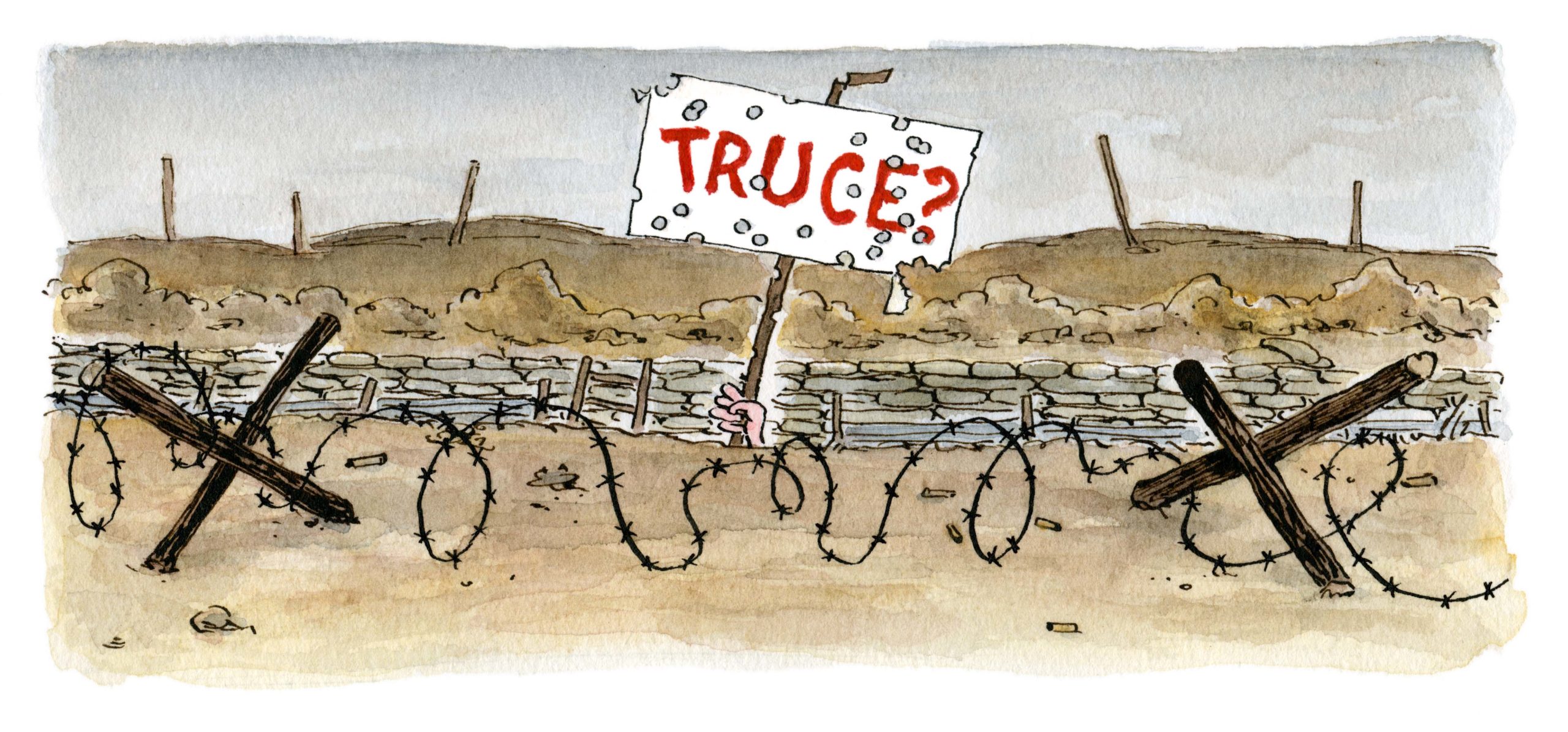

The Christmas Truce, which I learned about during a visit to Kansas City’s National WWI Museum and Memorial, entered my mind when I started thinking about an ideological conflict closer to home, the nation’s white-hot debate over guns and public safety.

It’s a war of words where the combatants have dug ever more deeply into their trenches. On many fronts, factions battle to a stalemate, at least at the federal level. On one side, there are those who believe that levels of gun violence in this country, made impossible to overlook by an onslaught of mass shootings, require new gun laws and restrictions. On the other, there are those who believe the personal right to bear arms is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution’s Second Amendment and sacrosanct. And while there may be a number of folks who fall in between those sides, their voices tend to not be the loudest in the debate.

We Are All Part of the Mess and Part of the Solution

I started thinking about our nation’s debate over guns and public safety in terms of trench warfare after I read through the responses of more than 500 Kansas Leadership Center (KLC) alumni who completed a demanding online survey on the topic this past August. The survey was sent out as part of KLC’s Journal Talks initiative, which encourages alumni from across the state to host thoughtful small-group discussions on tough issues. The KLC board of directors each year chooses a thought-provoking issue for the organization to focus on, and this year it is encouraging past KLC participants to convene community-level discussions on the topic of guns and public safety.

As I read through each of the responses that were submitted, I found myself thinking that the topic of guns and public safety is so emotional and polarizing that it’s difficult for even the most highly trained among us to get on the balcony—that metaphorical place where we get a broader, more detached view of a situation that’s unfolding before us. As skilled as KLC alumni are, everyone struggles to hold and test multiple points of views on the most hot-button issues.

On its face, this might seem a little depressing. If people who’ve been deeply immersed in learning how to diagnose situations, manage self, energize others and intervene skillfully can’t break the negative patterns of interaction on guns and public safety, then who on earth can?

But rather than leaving me discouraged, reading through all the survey results actually left me feeling hopeful. I was grateful that so many alumni trust the KLC enough to even fill out the survey and take it seriously. It suggests to me that hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of alumni care enough to take the risk of engaging in this difficult discussion with one another through Journal Talks, which will launch this month.

It’s a dialogue that will be especially rich because, despite having a common language of leadership, views about guns among alumni, like those of Kansans in general, are all over the map. Based on the survey, virtually every faction in the nation’s gun debate, from the strongest supporters of the Second Amendment to the biggest proponents of new gun restrictions and everyone in between, is represented among the ranks of KLC alumni. I can think of few networks operating in American society today that can draw from such a broad cross section of public opinion. In a country filled with echo chambers, it’s the rare example of a marketplace that can be put to use for the common good.

But to take advantage of that diversity, I think we all need to declare a few moments of armistice and spend some time on the balcony. I don’t expect the highly energized factions to take a full timeout from our nation’s vigorous debate over guns. What I expect is that more of us will take time out this year to reflect on the current state of the debate, what it means and what, if anything, might be done to make our discussion more productive.

During our brief moments of truce, we can spend some time talking not just about the issue, but also about how to move past some of the barriers that make society’s current debates over guns and so many other issues too circular and frustrating. Clues about the barriers that need to be surmounted can be found in the answers in that survey.

Barriers to a Better Debate

When I began reading what KLC alumni told us about guns and public safety, I started seeing patterns in the responses that revealed some of the biggest barriers to better discussions about highly polarized topics.

In all, I identified five key barriers that will be important to work through if we’re going to have those moments of truce that contribute to a better public debate.

Barrier No. 1

Experiences with guns vary widely in Kansas, and it can be hard to understand those with different frames of reference.

It’s quite common for KLC alumni to have a relationship with guns. A number of them own guns; some even carry them on a daily basis as law enforcement officers or concealed carry permit holders. There are hunters and people who use them for all manner of target shooting. Some use guns to protect their property from threats such as wild animals. Guns are viewed as tools or resources to be used responsibly for important safety or recreational purposes.

Others don’t handle guns themselves, but they have them in their households. Their spouses, siblings or offspring own and handle them. They might have long family histories with the use of guns. There are some who don’t own guns at all, but they still express strong support for people being able to own and use them in legal ways.

The largest percentage of KLC alumni taking the survey, about 45 percent, described themselves as having largely positive relationships with guns. But another substantial portion, about 30 percent, described guns in negative terms, or didn’t indicate having a relationship with guns at all. They talked about avoiding guns, disliking guns, even fearing them and people who enjoy using them. People can be conflicted, too, expressing a history with guns and concern about the types of guns that are available and how they are being used. Other respondents described their experiences with guns in completely neutral terms. Some even reject the premise that their past experiences can influence their opinion on the issue.

The answers show how the experiences Kansans have with guns could make talking about the topic tougher because we’re coming to the conversation from different places. It’s sometimes hard to understand why something that seems to make so much sense in one’s own mind seems completely foreign to somebody else. In some cases, survey respondents tried to imagine the thinking of someone who felt differently. Gun supporters imagined that gun opponents had experienced something traumatic related to guns in their lives that had influenced their opinions. But many struggled to fully connect the dots.

Having a productive conversation requires us to dig deeper and look at why people have the opinions they have. Instead of asking people about their positions, encourage them to describe their experiences and why their beliefs are important to them. We must listen closely even to those we disagree the most with. If you disagree with people on the substance of the issue and yet still come to understand why they feel the way they do and why it’s so important to them, that can make it easier for you to hold and test multiple interpretations.

Barrier No. 2

There’s a high degree of certainty about how to deal with the problem.

One of the most surprising results of the survey to me was the fact that about 62 percent of those surveyed were certain or very certain that the changes they desired were what was needed to deal with their concerns related to guns and public safety. This stands in stark contrast to the nature of an adaptive challenge, where there are no quick fixes and new learning must occur for progress to be made. It makes me wonder:

Do KLC alumni consider the issue of guns and public safety to be an adaptive challenge yet still want to treat it like a technical problem?

As I thought about it more, two factors may be influencing the way respondents see the problem. First of all, everyone has views, values, identities and groups that they are loyal to. In a sense, we’re certain because so many of those around us are certain. And in an emotionally charged topic like guns and public safety, there’s a sense of security to be found in certainty.

If we don’t know the right way forward, that’s a scary proposition to encounter. It means facing a threat – whether it’s being a victim of gun violence or having a right to own guns taken away—that has no defined counterweight to stop it. It may be easier to live in certainty that a solution to your problem exists and that other people stand in the way of it than it is to wrestle with the possibility that things are more complicated than you can fathom.

And yet anybody who has ever had the experience of arguing with someone who thinks they are completely right knows how frustrating it can be. It’s virtually impossible to persuade someone who’s dug in to change their position. Arguing with them only causes them to become more deeply entrenched. Many times, the dialogue related to guns and public safety seems to involve sides that mutually reinforce their intractability.

My advice is to avoid that trap. Don’t start a discussion on points where there is deep disagreement. You’ll only court frustration. Instead, focus the conversations on areas where there is curiosity. Where are you uncertain or willing to entertain multiple interpretations? The only path to enriching dialogue on this topic is by exploring what you’re willing to admit you don’t fully know or understand.

Barrier No. 3

It’s tempting to define the other side in the most negative terms possible.

In the Journal Talks survey, we asked respondents to imagine “someone who feels very differently from you in regard to this topic. How would you describe their position or way of thinking?” The answers were telling.

The word “extreme” and its variations (adamant, irrational, stubborn, reactive) popped up most frequently, 105 times over the 474 responses. Opposing viewpoints were described as wanting to take sweeping actions, such as “take all the guns” or “have guns everywhere.” Other common descriptions were “uninformed,” “closed-minded” and “ignorant.” Others described those with opposing views as “afraid” or “fearful.” These characterizations echo much of what I see on social media.

Again and again, it was difficult for respondents to answer the question without assigning some degree of judgment to the opposing view. Only a handful, about 55 of the 474 responses, seemed to be able to describe an opposing view in charitable enough terms that the other side might be tempted to agree with it. The interesting thing is that it’s not just one side that has a negative view of the other. Both pro- and anti-gun perspectives tend to describe opposing viewpoints in highly negative terms. It’s as if both groups are saying, “My beliefs are totally rational and based on facts. But those other people? They’re the extreme ones!”

Such mutual incomprehension calls for all of us to exercise a little more humility. First, let’s be honest with ourselves that as much as our views make sense to us, they might seem totally foreign to someone else. Rather than assuming that we’re rational and others are not, let’s start from a place of assuming that multiple perspectives have rational positions, however deeply we might disagree with them.

Second, rather than describing what someone else believes in the most negative terms possible, we will be better served if we can describe their position in ways they can agree with. This doesn’t mean I have to change my mind about what I personally believe; it only means that I take a moment to try to see the world through their eyes and show that I fully understand how they see it.

Does this mean that people will disagree any less? Possibly not. But considering alternative viewpoints can be threatening, and through being as charitable as possible, we reduce the likelihood of having a conversation become explosive. It’s hard to learn anything from anyone if your defenses are up. Being gracious to differing viewpoints allows for the possibility of true dialogue over arguments.

Barrier No. 4

Some people don’t want to talk about this topic at all.

Talking about tough topics such as guns and public safety is difficult and risky. While some have strong opinions, they are more than happy to share, there’s also a group of people who don’t want to say much at all. In the survey of KLC alumni, it wasn’t uncommon for respondents to say that they were willing to listen to all sides or that “everybody’s entitled to their opinion.”

Being respectful of different opinions is laudable, but just saying you are respectful probably isn’t enough to make productive dialogue possible. Real discussion requires engaging with different viewpoints deeply enough that you are able to ask questions and deeply understand and articulate them. It’s difficult and sometimes even painful work. The bottom line: Don’t just say you’re open to considering a different point of view. Demonstrate it through your actions.

There can also be a form of self-protection at play when one is reluctant to analyze the views of others. Engaging with alternative viewpoints in a dialogue might easily raise questions about one’s own views. If you don’t challenge views of others, then you might also avoid having your own views challenged in the process. On an emotional topic such as guns and public safety, it’s all too understandable that this is an inviting approach because it diminishes any chance of conflict. Using this approach, every view is equally valid. So, who’s to say whether my or anyone else’s views need to be re-examined?

But for a discussion and dialogue to have value, all sides need to be willing to give up something. If we can’t be persuaded, we at least have to be open to the possibility that we don’t understand something fully or could benefit from adding another vantage point to our spectrum of thinking. Everybody is entitled to their opinion. But it’s our willingness to discern, struggle with contradictions and ambiguity, and expose holes or gaps within our own thinking that makes the process of weighing different opinions worthwhile.

Barrier No. 5

We expect others to be neutral and fair but struggle to do it ourselves.

All too often, it’s easier to expect other people to behave better than we’re willing to act ourselves. We want others to be fair, trustworthy, unbiased and objective. But it’s human nature to see the confirmation of what we already believe in trying to analyze the factual basis of a story, poll or research paper. We spot others’ blind spots and fallibility far easier than we do our own.

The flaws that keep humans from being able to reason well shouldn’t stop people from entering into vigorous discussion. But they are a reason to enter each interaction with humility and a willingness to extend grace. So much of the dialogue that takes place in society on social media and elsewhere these days isn’t dialogue at all. It’s score settling. It’s a world of owning, getting owned and owning one’s self. But how do you know if you’re learning anything? How do you know if you’re gaining knowledge that will help you make the world of possibilities you see in your mind edge closer to reality?

The world of human interaction is a messy place. We should allow ourselves and others to be wrong, to make mistakes and to change our minds. We should be forgiving when other people stumble or anger us. Ask them to be forgiving of our own shortcomings, our own shoddy thinking or contradictory ideas. Because the truth is: We all mess up a bunch of the time.

If you want to change someone’s mind on guns and public safety, or pretty much any other topic, you need to be willing to have your own mind changed to some degree. Locked doors feel safer. But it’s open doorways that allow someone else to pass through to the side on which you stand. The danger is that you’ll be moved to take a step in their direction.

This, of course, it what makes taking time for a truce in the guns and public safety debate such a valuable opportunity. Participating in it means you don’t have to change your mind or sacrifice your beliefs. If you’re a stalwart supporter of the Second Amendment, you can still leave assured that the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun. Or if you believe that enough is enough and that stricter gun control is needed, you won’t have to change your mind. Or if you fall somewhere in between, you can remain there. You can return to the fray anytime you want.

“But if nobody changes their minds,” you may be asking yourself, “then what’s the point?” And if this was just about guns, you might be right. The truth is, though, that guns are just one flash point in a broader fight about defining the values, direction and priorities of this country. It’s a battle that pits residents of this state all too often against one another. And because the stakes are high, no one’s likely to surrender anytime soon. The key challenge isn’t our relationship with guns; it’s our relationships with one another.

Improving those relationships is going to require difficult discussions with lots of people who might think differently or come at the topic from different perspectives. These dialogues aren’t likely to produce quick fixes or some clear slate of legislative solutions. They’re more likely to feel confusing, frustrating and complicated. But if the relationships between those of differing viewpoints can change for the better, then maybe the quality of dialogue we have and the results it produces can, too. Maybe there are hidden connecting interests among the factions that will serve to lay a foundation of trust and dialogue. I don’t know. I can’t make any promises about what the outcomes will be.

What I do know is that I don’t want to stay in a trench anymore. I hope that over the next year you’ll join me outside, in the dangerous open, where there’s far less protection and far more potential for something meaningful to occur.

A version of this article was originally published in the Winter 2019 edition of The Journal, a publication of the Kansas Leadership Center. To learn more about KLC, visit the website.

Chris Green, a former statehouse reporter, is the managing editor of The Journal, the Kansas Leadership Center’s nationally award-winning print and digital magazine.