Sarah Lipscomb

In 2018, the National Civic League added a new element to the All-America City Award program. Applicants were asked to “Describe Civic Engagement in your Community” in a separate section of the application. The League made this decision to draw out more details on the civic engagement strategies for community-decision making processes, or what we call “civic infrastructure,” to highlight and share the important process of decision-making.

In 2018, the National Civic League added a new element to the All-America City Award program. Applicants were asked to “Describe Civic Engagement in your Community” in a separate section of the application. The League made this decision to draw out more details on the civic engagement strategies for community-decision making processes, or what we call “civic infrastructure,” to highlight and share the important process of decision-making.

The 2018 All-America City finalists and winners stepped up to the challenge of the new application section. They described a culture of engagement in their communities based on the formation of partnerships with all local institutions and residents that mitigated barriers to engagement, acknowledged the expertise that residents have to offer on decisions affecting their lives, recognized the equity gap in who makes decisions and turned talk into meaningful actions with positive effects.

Mitigating Barriers to Engagement

Meeting Residents in Their Spaces

With so many time demands on residents these days, it’s crucial to make engagement easy and less time consuming. By meeting residents where they go for other needs, local institutions can maximize their outreach and make good use of residents’ time. To gain more input from different voices, strategies that physically meet residents are necessary. For example, many cities around the country have mobile office hours. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina’s city manager hosts drop-in mobile office hours at various locations around Town. This includes riding a local bus route to speak with people during their commute and allows the manager to hear from people experiencing homelessness on their needs and ideas for the town.

Meeting residents where they are takes sustained practice. Longmont, Colorado leaders learned from experience in 1990 when an ordinance concerning RV parking was met with contempt from residents. They knew they had to be more intentional about including residents outside of the “regulars,” who did not represent the full demographics of the community. Partnering with community groups, the City of Longmont now makes it easier for residents to have a place at the table by meeting them where they are, whether it’s at the El Comité- a grassroots organization dedicated to providing advocacy and social services for Latinx, the local Peruvian festival, a teen mom support group, or various Chamber of Commerce events. This inclusive approach to public engagement has led to several community successes, among them, bringing a community college to Longmont, establishing a community theater, creating a more visually appealing downtown, and building an educational center for teens who perform poorly in traditional school settings.

When You Don’t Know – Ask

Residents are the experts when it comes to understanding their own lives and their own barriers to engagement. To get the full picture of barriers and to find what would encourage more engagement, it’s best to ask the residents. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, began its Government Outreach Strategy with an online survey, which asked respondents to rate their current engagement level, identify their preferred engagement method and to provide their opinion of potential engagement tools. This step ensured its outreach strategy was rooted in the information provided by those who would be affected by the strategy.

Residents are the experts when it comes to understanding their own lives and their own barriers to engagement. To get the full picture of barriers and to find what would encourage more engagement, it’s best to ask the residents. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, began its Government Outreach Strategy with an online survey, which asked respondents to rate their current engagement level, identify their preferred engagement method and to provide their opinion of potential engagement tools. This step ensured its outreach strategy was rooted in the information provided by those who would be affected by the strategy.

Placentia, California discovered that access to transportation was a barrier to engagement, but so were the safety concerns of traveling over opposing gang lines to get to transportation. Placentia provided safe transportation to those identifying this need to ensure their voices were heard in planning processes that would directly affect them.

When El Paso, Texas’ Neighborhood Services staff began meeting with various residents and neighborhood associations to understand the issues they faced, it became clear that some residents and associations were more effective at communicating their needs and championing their causes than others. Some associations even expressed their perception that a handful of associations garnered a greater amount of attention and response from local government. Analysis of the situation suggested that the neighborhoods with the strongest and best-informed leaders were significantly more capable of getting their issues addressed. The City developed the Neighborhood Leadership Academy (NLA) to train more effective leaders throughout the community to ensure equity in service provision.

Promoting Equity Through Inclusive Civic Engagement

The National Civic League is working to set a different expectation for engagement. “We tried to engage ‘them,’ but no one showed up” is not a high enough standard. Engagement of racial and ethnic minorities and others traditionally excluded from decision-making conversations is not going above and beyond. It must become the new expectation; the baseline for legitimate engagement efforts. Many of the 2018 All-America City finalists and winners described the innovative work they are doing to ensure equity in their engagement and decision-making.

El Paso, Texas requires those effected by policies to help shape them. For example, the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Steering Committee is charged with providing recommendations to City Council for the selection of infrastructure and social service projects that support low to moderate income neighborhoods. To ensure that the voices on that committee are representative of the interests of the population they seek to serve, appointees to the steering committee must reside in a low to moderate income neighborhood, or be over the age of 55, disabled, or homeless.

Beaverton, Oregon ensures those experiencing homelessness are part of creating solutions to housing affordability. The Voices of Beaverton project uses stories of residents to illustrate issues associated with housing affordability that are faced by many members of the community. The effort acknowledges that while data-informed decision-making is crucial, housing begins and ends with people. It highlights potential solutions offered by community members based on their life experiences.

Getting the Full Picture – Targeted Outreach and the Importance of Multiple Avenues

Setting the expectation of gathering input from those directly affected by decisions and aiming for input to be representative of the community’s broad demographics is no easy task. Improving targeted outreach strategies and using a multi-pronged approach to gather input can help reach that expectation, as seen in the El Paso and Beaverton examples.

The San Antonio Office of Equity and the SA2020 partnership applied an equity impact assessment to seven high-impact city government initiatives, including street maintenance, civic engagement to inform the budget, and boards and commissions. One assessment resulted in new outreach strategies. SA Speak Up reduced the gap between white and Latinx respondents by attracting 200 people to its first Spanish-language Community Night, a family-friendly event held in a park with food, activities, and health screenings.

Following a report on economic inequity in the city and a fatal officer-involved shooting in late 2016, Charlotte, North Carolina looked to engage the community in meaningful ways through its Community Letter Engagement Initiative. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Community Relations Committee and the Community Building Initiative provided a space for employees and community members to engage and share their points of view about race and police community relations and have open dialogue about matters that impact them and the community. Peer Perspectives (for city employees) and Can We Talk? dialogues (with the larger community) were forums offered in various locations with the goal of building trust and understanding.

More than 1,374 people participated in the dialogues over a six-month period. In addition to the dialogues, the city launched the second part of its Community Letter Engagement Initiative. Called Take10CLT, City staff and civic leaders shared information and materials about the content of the Community Letter and City goals, engaging in meaningful connections through personal conversations and receiving valuable feedback. They held ten-minute conversations to talk about important community issues. Notes on the conversations were compiled and analyzed to be used for decision-making and broader understanding. Residents were also connected with existing city resources when needs and opportunities were identified.

City staff also seized the opportunity to use the customer service phone ambassadors (part of Charlotte’s 311 call center), the Charlotte Youth Council and resident leaders from the Civic Leadership Academy to share information about the Community Letter and ask Charlotteans about what mattered most to them and their families when it came to safety, trust and accountability, affordable housing, and jobs. They also asked for their ideas on how to make Charlotte a better place for all people. The City of Charlotte reached nearly 8,000 residents with Take 10CLT and continues to capitalize on this engagement infrastructure and build on the relationships formed. The Community Letter Engagement Initiative, which comprised these two linked engagement efforts, facilitated dialogues and one-on-one conversations, reached almost 10,000 diverse residents, spanned racial demographics, and held conversations in multiple languages.

The City of Decatur, Georgia, has a long history of civic engagement practices. Its 2010 Strategic Plan was an update to the 2000-2010 Strategic Plan and was conducted over 12-months with more than 1,500 individuals participating in hundreds of individual meetings (many of them led by one of the 51 volunteer facilitators) and shared thousands of ideas to shape the direction of the Strategic Plan.

The process began with a series of roundtables, citizen dialogues in which participants talked about what they liked about Decatur and where the city should improve. From the five themes that emerged, a series of community academies, such as “Going Mobile – Managing Transportation Choices” and “Decatur For Life – Aging in Place, Affordability, Diversity,” were convened to educate the public about the tradeoffs related to issues over which compromise was needed. Input was expanded through the use of civic dinners, a cross between a roundtable focus group and a dinner party.

Continuing from the engagement foundation previously laid, in 2014 Decatur engaged a diverse group of residents and business people more deeply, creating the Better Together Community Action Plan for Equity, Inclusion and Engagement. The plan was designed to make Decatur a more welcoming, inclusive and equitable place to live, work and visit. A leadership circle of 19 participants worked together to design a visioning process to engage the community more deeply in conversations across differences and to intentionally reach out to include everyone – particularly residents who might feel marginalized and not welcome at the “table” to collaborate and create a Community Action Plan for Equity, Inclusion and Engagement.

Community members and city staff chosen to serve on the leadership circle brought different perspectives to the table. For example, the police chief was one of the circle members, as was one of the community members who had accused the police of racial profiling. Other perspectives included a middle school guidance counselor who is also Jewish; a Black, Muslim mother of teenagers who is a program director for a leadership program for teens; a Caucasian city staff member who is a native of Decatur and was at Decatur High during integration; a communications and marketing director married to a Latino immigrant; an African American male who is also a paraplegic; and more. All 19 had different backgrounds, stories, and strengths discovered and shared during the process.

Trust Can Be Eliminated in a Single Action, but Takes Sustained Action to Build

Establishing regular communication between historically left out groups and leaders can build trust and improve community capacity to address challenges. In Springdale, Arkansas, WelcomeNWA (Northwest Arkansas) and EngageNWA held several community and stakeholder forums to encourage dialogue. In 2017, EngageNWA held multiple forums that brought residents and leaders together from all walks of life to discuss race, LGBTQA, disability, language, gender, and age as it relates to the community and how people are treated, including their access to important services. The results of these forums were shared with local government officials and community leaders to help guide the work to address these issues in Springdale.

Stockton, California has been using engagement strategies to rebuild trust between residents and the police department. All police officers are trained in procedural justice and implicit bias, and the police chief has hosted more than 70 reconciliation sessions and “use of force listening tours,” listening to various community members speak about harms done to them by the police department and ways the department can rebuild community trust.

You Can’t Do It Alone – Supporting Resident-initiated Projects

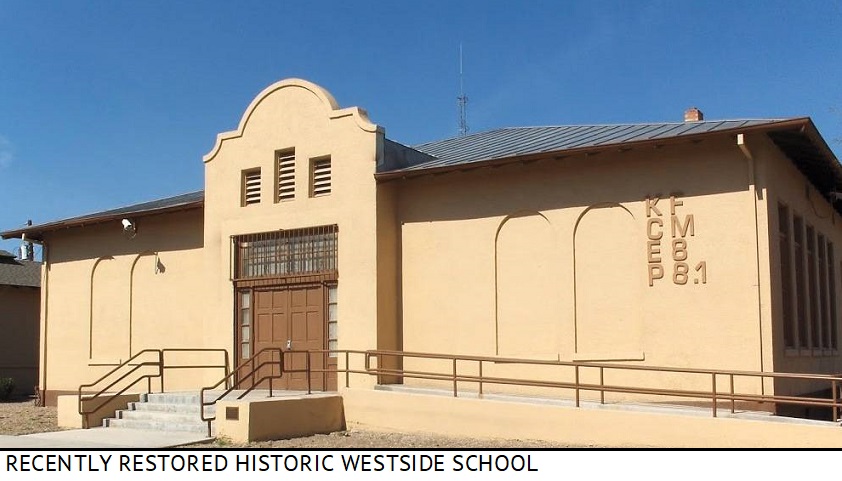

In an authentic engagement relationship, not only do local institutions initiate projects to address community concerns, they also recognize and support work the residents themselves are initiating to build stronger communities. In 2010, The Westside School Alumni Foundation (WSAF) was founded to preserve the historic Las Vegas Westside School site, educate the public on its history and value, and encourage the development of the vacant school as a cultural destination. The Westside School, which opened in 1923, was the first Las Vegas school to open its doors to African American and Native American students.

In 2016, the City passed a community development plan with the intention of revitalizing the Westside School community. The community was highly engaged in the visioning process and strongly encouraged to attend meetings and contribute ideas. The resulting plans from this process were incorporated into the Las Vegas 2035 Downtown Master Plan, making it an official city council-approved document to be incorporated into future development. Today, the school site stands as a testament to Las Vegas’ ongoing efforts to facilitate racial healing and community dialogue.

In Pasco, Washington, a police-involved shooting of an undocumented Latino resident captured on video garnered several weeks of national news coverage. The community erupted in protests and the City of Pasco responded by helping to plan a demonstration; Pasco police escorted the protesters, and officers later blocked off an entire intersection for the peaceful event.

City government’s support for peaceful protests helped establish a level of trust, and the police department updated its use of force policy through a community-based process, increased training for officers, hired more Latinx and Spanish-speaking officers and moved to use more mental health professionals in the field.

From Talk to Action

Gaining stakeholders’ input is only half of the engagement equation; making decisions and seeing outcomes based on that input is also crucial. Demonstrating how the input led to action helps keep people engaged. This doesn’t mean each suggestion needs to be implemented, but it does mean you need to show residents that you listened, considered and came to consensus on decisions.

Kershaw County, South Carolina was diligent in turning its visioning process into tangible outcomes. In 2015, the County developed VisionKershaw 2030 through a comprehensive visioning process that collected information from county residents, community leaders and business owners. The public engagement process lasted several months and included over 32 outreach events held at volunteer fire stations, churches, government buildings and schools. Staff offered workshops to a diverse cross section of organizations, including the local NAACP chapter and youth leaders.

Materials were available in Spanish, and staff answered questions during the annual multi-cultural festival. Taking what they learned from this visioning process, they developed an action plan outlining eight core long-term goals. Although it’s early in the 15-year plan, many actions have been accomplished, including improved existing recreation; planning for a new permanent downtown farmers market; reestablishment of the county’s Human Relations Board; completion of a detailed pedestrian, bike and greenway plan, finishing the first connector trail; passing a $129 million school board facility bond referendum and penny sales tax just two years after it failed; starting a mobile food pantry to serve food deserts; and expanding the number of EMS stations in underserved areas.

In Tacoma, Washington, sustained outreach to the Latinx community resulted in several positive actions. While Tacoma-Pierce County is only 10 percent Latinx, this population is growing, with many foreign-born residents. In 2016, Latinx activists worked with the City of Tacoma to produce two Latinx Town Hall meetings that attracted more than 250 attendees. As a result of the Latinx Town Halls, organizers formed Latinos Unidos del South Sound to continue working towards the goals from the two Town Halls. The group has a dedicated liaison with the Tacoma City Manager’s Office to serve as a conduit between the Latinx Community and the City. Another result of the town halls was an action by the Tacoma City Council in late 2017 to create the Commission on Immigrant and Refugee Affairs.

The variables of community decision-making are ever evolving – residents change, leaders change, issues change, new advances come along. Therefore, civic engagement work for local institutions is never truly done. Communities’ responses to the new “Describe Your Civic Engagement” section to the All-America City Award has reaffirmed the League’s mission and purpose. The sustained investment by these communities in creating a culture of engagement has resulted in more sustainable and more equitable solutions to the most complex issues. Continuing to advocate for strong civic engagement practices in communities across America, the League has released the 2019 All-America City Award application with a focus on creating healthy communities through inclusive civic engagement.

Sarah Lipscomb is Program Director, All-America City Awards and Community Assistance at National Civic League