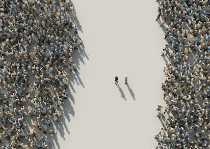

The belief in a hierarchy of human value is sustained by keeping people apart. In cutting off Indigenous people from their rights to self-governance and controlling access to such basic resources as food and water, colonization is the original form of separation, and it serves to benefit white society. Within the Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) framework, separation is defined as the division of groups based on a particular characteristic, including race and/or socioeconomic status. It is fostered by historic and present-day land use and development decisions that perpetuate racial inequities, such as segregation, colonization, and isolation, which lead to concentrated poverty and limit access to opportunity.

In fact, segregation has been deemed a form of “opportunity hoarding,” conferring benefits of homeownership, high-quality schools, and access to political power and other resources to white people.1 The effects are immense. It is estimated that 12% of children nationwide (8.5 million) live in areas of concentrated poverty. The concentrated poverty rate for Black and Indigenous children is 28% (for each) compared to just 4% for white children.2 These neighborhoods usually lack healthy food options and quality health care and have poorly performing public schools and higher rates of environmental exposures, all of which put Black and Indigenous children on a trajectory of poor health and limited opportunity across the lifespan and for generations. In the United States, separation has been codified into law at the federal, state, and local levels through both overtly racist practices such as redlining and school segregation, and covertly racist policies such as exclusionary zoning, the interstate highway system (which literally divided majority-Black neighborhoods in half), and school redistricting. The intent of these policies is also reinforced by habits and norms that were and are so pervasive that separation persists even though many discriminatory laws have been deemed illegal. In The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein writes, “if it becomes a community norm for whites to flee a neighborhood where African Americans were settling, this norm can be as powerful as if it were written into law.”3

Three primary areas that have been used to reinforce separation by race and ethnicity are housing, transportation, and education. Therefore, policies to address separation should ensure equitable access to these determinants and other resources essential for good health and racial equity.

Healing Through Policy elevates the following policy options for addressing separation:

- Zoning innovation for health and equity.

- Displacement and eviction protections to preserve the right to housing.

- Equitable transportation and planning to improve access to opportunity.

- School integration to promote social justice and social mobility.

It is also recognized that there is a broad range of environmental justice concerns that both perpetuate separation and exacerbate inequities within and between communities. While those specific environmental justice policies are beyond the current scope of Healing Through Policy, there is acknowledgement that the policy options listed below should incorporate principles of environmental justice and aim to reduce exposures to environmental hazards among communities of color.

Zoning Innovation for Health and Equity

Land-use policies have contributed to a great divide in our country, producing sprawling places, including neighborhoods and schools, that are marked by a stark separation of both uses and people. Zoning is the most common form of land-use regulation. The history of zoning laws to separate people by race dates to the early 20th century. In 1910, Baltimore adopted the first zoning laws that were openly drawn to keep African Americans and whites separated by laws that restricted Black residents to certain blocks. Explaining the policy, Baltimore’s (then) mayor stated, “Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidence of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby white neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the white majority.”4 Soon after, there was a surge in the employment of municipal zoning strategies to enforce separation by race and class. Over the next 20 years, the number of cities with zoning ordinances grew exponentially — from eight in 1916 to 1,246 in 1936.5

Land-use policies have contributed to a great divide in our country, producing sprawling places, including neighborhoods and schools, that are marked by a stark separation of both uses and people. Zoning is the most common form of land-use regulation. The history of zoning laws to separate people by race dates to the early 20th century. In 1910, Baltimore adopted the first zoning laws that were openly drawn to keep African Americans and whites separated by laws that restricted Black residents to certain blocks. Explaining the policy, Baltimore’s (then) mayor stated, “Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidence of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby white neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the white majority.”4 Soon after, there was a surge in the employment of municipal zoning strategies to enforce separation by race and class. Over the next 20 years, the number of cities with zoning ordinances grew exponentially — from eight in 1916 to 1,246 in 1936.5

After racial restrictive covenants were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948, covert practices followed. Many communities began to adopt “economic-based” zoning laws that required minimum lot sizes and the exclusive construction of single-family homes. Since Black families were largely prevented from owning homes because of affordability concerns or discriminatory lending practices, this effectively created all-white neighborhoods. These “exclusionary zoning” policies are still in effect in many neighborhoods. Exclusionary zoning ordinances contributed to patterns of pervasive racial segregation that characterize American neighborhoods today.

Zoning can and is being used as a creative tool for localities to address systemic inequities caused by separation.

Policy Examples

Examples of zoning innovation include:

Up-zoning; removing restrictions on single-family zoning/minimum lot sizes/parking requirements: Up-zoning refers to the lifting of common restrictions that reserve cities’ land exclusively for only one house per one large lot to allow for the development of more affordable housing options. Further, up-zoning also includes policies that unbundle housing and parking costs by eliminating parking minimum requirements for housing development sites or providing incentives to reduce parking construction in transit-rich areas. Reducing or eliminating these costly requirements around transit stops in walkable neighborhoods or on properties with affordable housing can improve housing affordability.

Minnesota’s comprehensive plan eliminates single-family zoning. This city-wide zoning reform is a direct effort to confront its history of redlining and segregation. In Miami, a citywide form-based code makes gentle density and missing middle-income housing more economically viable by eliminating the parking requirements attached to housing development in urban neighborhoods. Seattle requires developers to unbundle parking costs from housing costs so that only those who need parking are required to pay. Seattle’s policy also allows denser construction in and around 27 neighborhood hubs while requiring developers in those areas to contribute to affordable housing by including low-income apartments in their buildings or by paying fees.

Inclusionary zoning (IZ): This type of zoning requires or encourages the creation of affordable housing units when market-rate housing is developed, with the primary goal of providing opportunities for families at all income levels to move to low-poverty areas. IZ is intended to create affordable, below-market housing that would otherwise not be created by private developers. There are different types of IZ policies: Voluntary IZ policies utilize financial incentives such as expedited permitting and density bonuses for proposed projects that include affordable units. Mandatory IZ policies require affordable units to be included in all proposed projects covered by the policy. Mandatory IZ policies may also include financial incentives to new developments to offset the anticipated revenue lost by including affordable units.

There are 866 IZ housing policies located in 25 states and Washington, D.C., in large cities like New York City and San Francisco, in suburban areas such as Montgomery County, Maryland, and in rural areas like North Elba, New York. It must be acknowledged that IZ policies may be politically difficult in some jurisdictions. In fact, six states expressly preempt mandatory IZ laws: Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin. In addition, Virginia has limits on mandatory IZ and Colorado prohibits mandatory IZ rental laws (mandatory homeownership IZ laws are permitted). Another challenge with IZ policies is that many of them do not target very low-income households. Over half (53%) of IZ policies require units to be affordable to households with incomes between 51% and 80% of the local area median income (AMI); only 2% of programs target households with incomes below 50% of AMI.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs): Also referred to as “in-law suites” or “granny flats,” ADUs are smaller, independent units on the same lot as a single-family home, sometimes even an extension or a reworking of the home itself. ADUs can be a more approachable means of increasing affordable housing units in existing neighborhoods since they can be designed to blend in with the surrounding architecture, maintaining compatibility with established neighborhoods and preserving community character.

Furthermore, since ADUs can be connected to the existing utilities of a primary dwelling, there is no need to develop new infrastructure. Allowing ADUs facilitates efficient use of existing housing, helps meet the demand for housing, and offers an alternative to major zoning changes that can significantly alter neighborhoods. ADUs have the potential to increase the number and variety of housing choices in single-family zones, improve affordability, and decrease potential economic displacement.

Many cities across the United States are easing restrictions on ADUs to increase affordable housing options. In 2016, Seattle adopted an ordinance removing barriers to creating attached and detached ADUs. The new rules removed the requirement that homeowners in single-family zones live onsite, allowing ADUs to be built on rental properties. They also stopped requiring an off-street parking spot for each ADU, allowing homeowners without off-street parking to rent out ADUs, and eased size restrictions.

Los Angeles won a $1 million grant through the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Mayors Challenge to fund a program that will pair homeless residents with homeowners who have space on their properties for an ADU. Austin, Texas approved a series of reforms that accelerated the number of permits for ADUs as part of its larger efforts to improve affordability. Many cities in Northern California, including Berkeley, Oakland, and Redwood City, along with others nationwide (including Honolulu; Portland, Oregon; and Cambridge, Massachusetts) have already loosened restrictions on ADUs, and others are considering similar rule changes.

Given the longstanding race-based differences in homeownership rates and household incomes, there may be some inherent equity issues with ADUs that must be considered and addressed. One racial equity analysis of ADUs in Seattle found that white households are significantly more likely to own a single-family home and have the financial resources needed to add an ADU to their property. ADUs support affordability in an informal sense because renting an ADU tends be affordable to more households than renting a single-family house. This is likely due to the smaller size and lack of additional land costs to create an ADU. However, high construction costs mean that most households able to create an ADU are disproportionately wealthy or have access to substantial equity in their home. Further, though ADU rents may be lower than renting a single-family home, they are not low enough to provide housing that is affordable to households with lower incomes.

Zoning for food justice: The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that 54.4 million Americans live in low-income areas with poor access to healthy food. Zoning may also be used to address food apartheid and provide healthy, affordable food options.6 For example, localities may ease or create exceptions to zoning requirements to support and incentivize healthy retail. Philadelphia relaxes zoning height, floor area, density, and parking requirements for new fresh food markets that meet certain accessibility and siting requirements. Birmingham, Alabama, updated its zoning laws to help increase healthy food retail in the city by creating a Healthy Food Overlay District. Grocery stores in and within a half mile of the Healthy Food Overlay District enjoy reduced parking requirements and larger floor area allowances.

In Tribal communities, land use and zoning policies have also made it more difficult, and in some cases criminal, to exercise traditional food practices, including the cultivation of Indigenous foods, hunting, and fishing. For these communities, food justice is in the form of food sovereignty, which must be facilitated through honoring treaty rights, including hunting and fishing rights, and upholding policies that ensure access to and safety of traditional foods.

Evidence for Improving Health and Racial Equity

As illustrated above, there are many ways that zoning can be used to reduce separation and improve health and racial equity by addressing a few key determinants of health and equity. Thoughtful equity-informed zoning policies can promote the health, safety, and quality of life for communities, and bolster economic opportunity and equity by increasing availability of affordable housing, building wealth through homeownership, and creating or preserving mixed-income neighborhoods.

For example, IZ can increase access to quality affordable housing and decrease health disparities, and may increase neighborhood socioeconomic diversity. Also, while research on the impact of IZ policies on economic integration is limited, it suggests that IZ generally improves economic integration and provides low-income residents access to high-opportunity neighborhoods.

A RAND Corporation study of 11 cities across the country found that over three-quarters of affordable housing units developed through IZ policies were in low-poverty neighborhoods that had higher rates of employment and college attainment.7 IZ may also increase economic opportunity by improving educational outcomes for children. One study found that elementary school students in IZ-produced housing assigned to low-poverty schools performed better in reading and math than students in public housing assigned to moderate-poverty elementary schools.8 Additionally, while IZ homeownership programs typically target a population with generally higher income than renters, recent analyses suggest that IZ policies can increase economic opportunity through access to home equity for low-income households.9

A study of units built in Montgomery County, Maryland and in Suffolk County, New York found that on average, tracts where IZ units were built became more racially integrated than neighborhoods without IZ units.

ADUs can support aging in place, which helps improve the health and well-being of older adults through a greater sense of autonomy, connection to family and social networks, and affordable living situations. This latter point is especially important for older adults of color who are more likely to live on a lower fixed income and in poverty. ADUs can also encourage greater age diversity within a neighborhood of young adults and senior citizens.

Displacement and Eviction Protections to Preserve the Right to Housing

An estimated 43.1 million Americans rent their homes — the highest rental rate in the last 50 years.10 As a group, renters are at higher risk for housing-related health problems because they have fewer resources and/or they face compounding health burdens, which can be exacerbated by unsafe, unstable, or unaffordable housing. Typically, renter households have lower incomes than homeowners and have very little savings or wealth.11 Though most renter households are white, people of color are over-represented as a group. Black and Latinx households are twice as likely as white households to rent their homes. In 2016, 58 percent of Black household heads and 54 percent of Hispanic household heads were renters, compared with 28 percent of white household heads.12

Also, two-thirds of renters are either over age 50 or are families with children. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, one study estimated that one in five renters struggled, or were unable, to pay their rent and that 3.7 million Americans are evicted every year.13 At the end of 2020, an estimated 40 million renters were at risk of eviction, 80 percent of them being Black or Latinx. While the emergency measures currently in place provide a temporary relief from eviction for some, more long-term strategies are needed to protect renters’ right to housing.

Policy Examples

Keeping people, many of whom are the most vulnerable and in need of a safety net, housed must be a key strategy for advancing racial equity.

Right to return or preference policy: These policies are an effort to address the harmful impacts of gentrification by giving priority placement to residents who were displaced, are at risk of displacement, or who are descendants of households that were displaced. Portland Oregon’s Preference Policy gives priority placement to housing applicants affected by urban renewal in North and Northeast Portland.14 While older policies in New York City; Oakland, California; and San Francisco have all tried to give residents of gentrifying areas preference when a subsidized apartment building becomes available in their neighborhood, no city gave preference to residents who live outside a neighborhood based on their parents or grandparents having lived there until Portland’s measure. Austin, Texas has piloted a similar policy.

Portland’s Preference Policy is a strong example of an anti-gentrification and displacement policy that also seeks to redress past harms. The city has successfully offered over 100 units to individuals who were displaced. It has also passed an IZ ordinance that allows for expansion of the preference policy into other districts.

Right to counsel: Having the assistance of a lawyer in housing court can mean the difference between staying in one’s home or losing it. A 2017 Legal Services Corporation report found that 86 percent of all civil legal problems for low-income people nationwide receive insufficient or no legal help.15 Right to counsel laws seek to redress the imbalance of power between tenants and landlords in housing court. First enacted in New York City, the legislation requires that, subject to appropriation, the city provide access to legal representation to all eligible tenants by 2022. In the program’s first year (FY 2018), legal representation, advice, and assistance were provided to 33,000 households, including 26,000 facing eviction proceedings, and ultimately more than 87,000 city residents benefitted. Overall, nine cities have established right to counsel for housing discrimination, and seven have for evictions.

In 2018, San Francisco voters approved a ballot measure guaranteeing all tenants a right to counsel in eviction proceedings. Washington, D.C.’s Expanding Access to Justice Act requires the DC Bar Foundation to provide representation in “certain civil cases” to people under a set income threshold. The Philadelphia City Council appropriated a half million dollars to give low-income renters legal representation in housing cases. Other jurisdictions that have considered or piloted this approach include Newark, New Jersey; Los Angeles; and Hennepin County, Minnesota. Cleveland is exploring how to guarantee legal counsel for indigent tenants in eviction cases and studying the potential impact of a right to counsel on the community.

Just cause eviction: Just cause eviction is a form of tenant protection designed to prevent arbitrary, retaliatory, or discriminatory evictions by establishing that landlords can evict renters only for specific reasons such as failure to pay rent. Oakland, California passed the Just Cause for Eviction Ordinance in 2002, which includes 11 legally defined “just causes.” In 2017, San Jose, California enacted the Tenant Protection Ordinance implementing just cause protections. The protections, which apply to all rental units, impact 450,000 renters citywide. Other jurisdictions with just cause eviction policies include Baltimore; Boulder, Colorado; Cleveland; Newark, New Jersey; New York City; Philadelphia; and San Francisco.

Promise for Improving Health and Racial Equity

Preserving the right to housing, especially for renters, impacts both health and racial equity by preventing housing instability, which is associated with a range of negative health effects. These include increased physical and mental health issues, and disconnection from social networks and health-promoting resources such as health care and healthy food options. Children experiencing housing instability are more likely to experience hunger, chronic absenteeism, and behavior challenges that lead to disciplinary actions, all of which increase their likelihood of underperforming and not graduating from high school — a significant predictor of poor health across the lifespan.

The proposed policies also attempt to protect renters from susceptibility to displacement due to dramatic increases in market value of rentals caused by gentrification. Studies have found that populations displaced by gentrification have shorter life expectancies and are more likely to report poor/fair health,16 higher rates of preterm birth,17 and higher incidence of chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.18 19 20 Mental health outcomes, including an increased risk of psychological stress levels and depression, have also been demonstrated among displaced populations.21 Displacement and eviction protection policies have been criticized for being helpful for individual households but not addressing systemic issues such as the structural racism baked into common housing and finance practices. These policy options should be applied in concert with broader equitable zoning, housing, and development strategies.

Equitable Transportation and Planning to Improve Access to Opportunity

Transportation is a key determinant of health. It can facilitate or limit one’s ability to access jobs, education, healthy food, social engagements, faith-based institutions, and health care. The legacy of the transportation system in the United States reflects its roots in racism designed to segregate communities.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 resulted in an unprecedented amount of investment in the transportation infrastructure of the country. However, the racism and racial bias that existed at the time drove how and where these dollars were used. This allowed policymakers, engineers, planners, and private businesses to use racist practices to destroy neighborhoods by using highways to literally divide neighborhoods in half; increase reliance on personal automobiles to jobs, goods, and services; support construction and investment in white suburbs; and concurrently divest in all-Black urban neighborhoods.

In the 21st century, as the public health community began to recognize and actively promote the importance of neighborhood conditions for health, there was a corresponding shift in preference for more walkable communities and a resurgence of people returning to cities. The resulting rise in living expenses in cities displaced lower-income and lower-wealth families. And now, in many large cities, higher-income white residents have the political and social capital to drive decision-making that results in transportation and development projects being concentrated in wealthier and whiter parts of urban areas. In addition to displacement, the result is widening disparities in access and opportunity for remaining residents.

Policy Examples

To reduce these inequities, transportation and planning policies and practices must embed considerations of equity at all levels and be driven by the needs and priorities of impacted communities.

Incorporation of equity goals and equity-driven processes into the fabric of agency planning and policy decisions: This could include explicit racial equity goals and objectives in comprehensive plans and/or requiring considerations of racial equity in transportation and planning decisions, such as through equity impact assessments or other racial equity tools. Such plans should also incorporate principles of environmental justice and include robust provisions for community engagement that include ongoing opportunities for community involvement in all levels of project planning and implementation.

Akron, Ohio’s new Office of Integrated Development launched a five-year strategic framework listing equity as a core value for planning and established a goal of a “more equitable Akron.” The 2050 transportation plan for Washoe County, Nevada’s Regional Transportation Commission outlines a path toward “promoting equity and environmental justice.” In May 2015, Seattle passed a resolution making race and social equity a foundational core value for the city’s Comprehensive Plan. The resolution requires incorporation of new race and social equity goals and policies throughout the plan; analysis of the impacts of proposed growth strategies on the most vulnerable communities; reduction of racial and social disparities with capital and program investments; and creating, monitoring, and reporting on equity measures.

Transit-oriented development that prioritizes affordability and equity: One of the most direct means of connecting low-income people to high-quality transit is to build affordable housing nearby through transit-oriented development (TOD). TODs can also drive displacement, so transit agencies must take care to avoid exacerbating affordability issues from the outset of the planning process by including strong affordability requirements. Mechanisms for supporting TOD include:

- Joint development agreements: Washington, D.C.’s Metropolitan Area Transit Authority requires affordable housing development on land it controls, for example, requiring 20 percent affordable housing units. Los Angeles’ joint development program requires that 35 percent of the total housing units in the metro joint development portfolio be affordable for residents earning 60 percent or less of the area median income.22

- Transit-oriented development funds: Dallas Area Rapid Transit allocates 20 percent of TOD funding to affordable housing development. The Denver Regional Transit-Oriented Development Fund has spurred the community-driven creation or preservation of more than 1,000 affordable housing units near new light rail stations. San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit requires a minimum of 20 percent affordable housing units in station TODs and has set a more ambitious target of 35 percent.

Unfortunately, low-income residents and communities of color often bear the burden of unintended impacts of TOD. Several studies have characterized TOD impacts as promoting economic development, elevating property values, and enhancing livable environments, but these impacts are not equally distributed.23 24The resulting “Transit-induced gentrification (TIG)” is defined as “a phenomenon whereby the provision of transit service… and associated area of development change in the direction of neighborhood upscaling.”25

Simulation studies in metropolitan Washington, D.C. communities found that affordability restrictions placed on TODs worked better than housing vouchers for keeping low-income families closer to transit stations. This study went on to recommend that policies focus on developing affordability requirements for TODs.26 Another strategy localities can employ is to reserve low-priced land at an early stage of TOD to provide the grounds for the construction of affordable housing. Reserving and protecting land before gentrification occurs can ensure affordable housing units for low-income households when land and housing prices begin to rise. To ensure TOD is equitable, the policy and its associated programs and financing tools must support the creation of mixed-income communities.

Income-based fares for public transit. Transit access practices such as fare policies should target high-need communities and reduce financial burdens on low-income transit riders. Fare-capping policies create a de-facto payment plan for low-income riders, for whom it can be a burden to pay the up-front cost of a monthly unlimited pass. In King County, Washington, residents with incomes less 200 percent FPL are eligible for $1.50 transit fares. Portland, Oregon’s TriMet riders at or below 200 percent FPL are eligible for half-price adult single and day passes, as well as 72 percent off monthly and annual passes. Other jurisdictions include Albuquerque, New Mexico; Dallas; Madison, Wisconsin; Pima County, Arizona; and San Jose, California. In summer 2020, Washington, D.C. launched a low-income fare pilot program.

One of the primary ways that transportation drives health and racial equity is its ability to connect people to employment, and thus, income. Access to reliable transportation is a key factor in whether an individual can attain or hold a job. For most people, reliable transportation means having access to a car. However, car ownership places an undue burden on low-income households, leaving them in a precarious and vulnerable position that is further compounded in many low-wealth neighborhoods that lack multimodal transportation choices. Without access to transportation options like public transit, walking and wheeling, or biking, those who live in auto-centric communities are more likely to fall into poverty due to transportation-related emergencies. These challenges are further exacerbated for people living in rural communities, with no access to transit and long distances between destinations.

Transportation and planning infrastructure in a community is also directly connected to health through its conduciveness (or lack thereof) to physical activity. Unfortunately, many communities do not have the infrastructure to support safe walking and biking to everyday destinations. Evidence shows very limited public investments are made in low-income communities to improve roads, sidewalks, lighting, and other transportation infrastructure that would improve people’s everyday mobility, physical activity, and safety.27 28 29A study of income disparities in street features that encourage walking found that streets with street and/or sidewalk lighting, traffic calming, and marked crosswalks were significantly more common in higher-income communities than in middle- and low-income communities.30

School Integration to Promote Social Justice and Social Mobility

While the American populace has grown increasingly racially and ethnically diverse over the last several decades, our schools have gone in the opposite direction and are marked by astounding racial and socioeconomic segregation: As of 2019, more than half of U.S. students were located in “racially concentrated” districts where more than 75 percent of students were either white or non-white.31 Due to the combination of a history of racist housing policies and a reliance on the local property tax base to fund public schools (and because a majority of students attend their neighborhood public schools), these same students are often subject to double segregation by both race and class. Black and Latinx students are more than five times as likely as white students to attend high-poverty schools, and three times as likely as Asian American/Pacific Islander students.32 In schools with concentrated poverty, where poor students fill 90 percent or more of available seats, 80 percent of the students are Black and Latinx; in contrast, more than 50 percent of white students attend schools where fewer than 30 percent of the overall student body is poor.33 As a result, Black and Latinx students are disproportionately enrolled in schools that are simultaneously tasked with not only teaching, but also expending significant time and resources to address the intersecting race- and class-based disparities their students face before they reach the classroom — all with far fewer resources than predominantly white schools.

As of 2019, predominantly white school districts in the United States received $23 billion more in annual funding than predominantly non-white school districts despite serving a nearly equal number of students — a difference equating to $2,226 more per capita.34 States and localities have the option to pursue compensatory spending to address this disparity and improve educational outcomes for students of color, directing additional funding to schools characterized by racial and economic isolation. However, research indicates that integration efforts offer both better academic and life outcomes for students and a better return on investment for policymakers.35 More than that, school integration serves to push back against an acceptance that schools are and will continue to be segregated, and that such segregation — should we just manage to even out test scores — is an acceptable outcome.

Policy Examples

School integration efforts are varied, and a growing number of local education agencies are undertaking the work. As of December 2020, more than 180 school districts and charter schools consider race or socioeconomic status in their student assignment or admissions policies, and approximately a quarter of the active policies were implemented in the past four years.36 Nationwide, local education agencies typically embrace some combination of three policies: socioeconomic-aware controlled choice enrollment and transfer processes for public schools, race- and income-aware school attendance zones and feeder patterns, and expanded school choice via magnet and charter programs.

Controlled choice enrollment and transfer processes prioritizing socioeconomic integration: While most U.S. students attend the public school zoned for their home address, districts have the option to introduce controlled choice into public school enrollment processes as a means of ensuring demographic parity. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, a “controlled choice” enrollment process — which first replaced neighborhood schools in 1981 — considers family choice in student placement, but also factors in socioeconomic status to ensure that district-level demographics are reflected in each school. In 2020, Washington, D.C., — a city in which public school students are split almost equally between district and charter schools — passed legislation allowing charter schools to implement a preference in the citywide enrollment lottery to prioritize students who are eligible for public benefits, experiencing homelessness, involved in the foster care system, or overage in high school. Similar policies exist across the country, including in Eugene, Oregon; Denver; Newark, New Jersey; San José, California; and St. Paul, Minnesota. In addition, several districts consider socioeconomic status as a factor in student transfer requests, a measure which helps counter the role inter- and intra-district transfers otherwise play in increasing school segregation.

Attendance zones and feeder patterns constructed to ensure racial and economic diversity: Persistent housing inequities and residential segregation continue to pose a significant hurdle to school integration, but school zones need not be set in stone. In 2016, The Century Foundation identified 38 school districts that had intentionally redrawn attendance boundaries, which define the geographic areas in which students must live to attend specific schools, to increase socioeconomic diversity.

One example comes from the Unit 4 School District in Champaign, Illinois, which periodically redraws the geographic attendance zones for its two high schools to reflect changing neighborhood demographics and ensure both racial and socioeconomic parity. This, combined socioeconomic-aware controlled choice elementary enrollment policies and accompanying elementary-to-middle feeder patterns support full K-12 school integration.

In Connecticut, Stamford Public Schools draws its attendance zone boundaries so that in any given school the share of “educationally disadvantaged” students who qualify for free- or reduced-price lunch, live in public housing, or are English language learners is within 10 percent of the district average.

Expanded public school choice for families through inter-district, magnet, and charter offerings: In Minnesota, the Burnsville-Eagan-Savage Independent School District prioritizes placement in magnet schools for low-income students, an effort that has helped bring 96 percent of schools within 20 percent of the overall district poverty rate. In Rhode Island, Blackstone Valley Prep Mayoral Academy — a charter network enrolling students from communities across the northern part of the state — reserves at least 50 percent of seats for low-income students, resulting in broad integration across socioeconomic, racial, linguistic, and disability status.

In Connecticut, Hartford Public Schools offers special enrollment opportunities for both intra-district and inter-district students, the former at schools in neighboring suburban districts and the latter in themed non-magnet public schools within Hartford limits. In their 2016 reporting, The Century Foundation identified 25 districts with magnet schools that considered socioeconomic status in their admissions processes, including Duval County Public Schools in Florida and New Haven Public Schools in Connecticut, and one district — Santa Rosa City Schools in California — with a centralized charter school admissions policy that reserved seats for at-risk students in schools with below-average enrollment.

But school integration is more than the doing away of all-white or all-Black schools or achieving demographics that adequately mirror, or even surpass, the racial diversity of a community. As policymakers work to diversify student enrollment, education leaders at all levels, including those working in school and district administration, need to understand that true integration is not simply about student demographics. Integration involves the many facets of school life that shape the student experience, including staff representation, curricular content, disciplinary practices, academic tracking, and overall school climate.

Evidence for Improving Health and Racial Equity

The public health impacts of racial and socioeconomic school integration are realized through improvements in three key metrics: educational attainment rates for low-income students and students of color, racial attitudes for students of all backgrounds, and social capital.

Graduation rates: High school graduation is a stark predictor of health and well-being across the lifespan. Compared to high school and college graduates, adults who do not complete high school are at higher risk of poor health and are more likely to die prematurely from preventable conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and stroke. Dropout rates are significantly higher for students in racially and economically segregated schools than in integrated schools.37

Research has consistently shown that students in racially and socioeconomically integrated schools — regardless of family background — perform better on standardized tests than their peers in schools with concentrated poverty, and that the achievement and graduation gaps between Black and Latinx students and their white peers are markedly smaller in mixed-income versus high-poverty schools.38 In contrast, the negative academic impacts of racially segregated schools on Black students have been documented as early as first grade, and overall achievement for Black students is lower in highly segregated schools even after controlling for income.39

Racial attitudes: A growing body of literature links racism to poor physical and mental health outcomes for communities of color, and a growing number of jurisdictions are responding with declarations of racism as a public health crisis. Successful efforts to address the crisis hinge on recognition of racism at both the individual and systems levels and across ages. Research demonstrates that children living and educated in racially segregated settings are at greater risk of developing racial stereotypes than their peers in racially diverse settings, and that white students represent the group currently most likely to learn in segregated settings.40 However, children educated alongside peers from multiple racial and ethnic groups, regardless of their own racial and ethnic background, hold fewer discriminatory attitudes and prejudices and are more likely to develop cross-racial relationships. They are also more likely to live and work in diverse settings five years after high school graduation.41 While such benefits are documented at all educational levels, results are strongest for integration efforts undertaken in the earliest grades before children have a chance to internalize racist attitudes.42

Social capital: When wealth is concentrated in just a subset of schools, so, too, is access to power through social networks. While compensatory spending serves to equalize government spending in schools, school integration redistributes not only funding but also access to the language and culture of the middle-class and white society — the gatekeepers to opportunity after high school. This social element is crucial for Black and Latinx students as they consider both higher education and employment, given the racial bias embedded in the selection and retention practices of each.

While Black students made up 13 percent of the undergraduate population in 2018, they represented 29 percent of the student body at four-year private for-profit colleges, which lead to both lower earnings and higher debt for students than at public institutions. In contrast, only 8 percent attended an elite research institution.43 44Meanwhile, Latinx students were concentrated in public institutions and were overrepresented (27 percent of students) in two-year degree programs.45 In the workplace, there has been little to no change in hiring discrimination against Black and Latinx applicants in nearly three decades.46 Diverse school settings facilitate access to the connections, recommendations, and social knowledge Black and Latinx students need to access, let alone thrive in, historically and predominately white spaces of power.

Racial and socioeconomic school integration has proven to be one of the most powerful strategies to improve outcomes for students of all backgrounds. Following the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, significant efforts to integrate schools occurred for only about 15 years nationwide, but this period is associated with perhaps the most equitable education, economic, and health outcomes for Black Americans in U.S. history. During this time, Black individuals experienced dramatic improvements in educational attainment, earnings, and health status (improvements that did not come at the expense of their white peers) with length of exposure to integration and strong school funding correlated with increasingly better outcomes in adulthood.

Such benefits were cross-generational, reaching not just those individuals who attended desegregated schools, but also their children; in addition, many of these benefits transcended race, with improvements in academic and broader life for white Americans, as well. In short, while some have argued that Brown-era school integration policies failed, the failure can instead be traced to an inability to prioritize integration over time.

Feasibility

Such deprioritization of integration efforts can be traced to concentrated efforts by white communities and their legislators to maintain segregated systems, and this localized resistance remains a considerable barrier to school integration. Attendance zones provide a concrete example: While cities and states have the opportunity to use geographic attendance zones as a force for integration, most districts — especially those experiencing rapid changes in racial demographics — draw them in ways that intentionally recreate and even heighten residential segregation. Even when school boards implement school zones that supersede residential segregation — an act that is more common with left-leaning boards — white residents tend to undermine the opportunity for integration by pulling their children from the public school system. Such undermining takes the form of both individual and collective choices, with 71 communities making an attempt to secede from their local school district between 2000 and 2016.47 White families with means will always hold an inordinate amount of power over the success of voluntary school integration plans, but efforts to capture and potentially leverage the buy-in of these families stand a chance to dramatically reshape outcomes for students of all backgrounds.

ENDNOTES