By Scott Bruun

The Affordable Care Act (or “ACA”) is now nearly 10 years old, yet the partisan rancor and widespread political mistrust that arose during that bitter debate seems as strong today as it was when the bill was signed into law by President Obama. Many Democrats saw the ACA as a guarantee for the fundamental human right of health care, while Republicans largely saw it as an afront to personal liberty and fiscal responsibility. These sentiments have changed little over the intervening decade. Yet for all the debate and animosity, then and now, there remains one aspect of the law that most members of Congress, and certainly most Americans, agree on: the need to protect coverage and access for patients with pre-existing health conditions.

Protections for coverage and assurance of access to care for the tens of millions of Americans with pre-existing medical conditions enjoy strong, bipartisan Congressional support to this day. In fact, it was uncertainty around the strength and veracity of protections for patients with pre-existing conditions that derailed Republican efforts to “repeal and replace” the ACA during 2017 and 2018, despite significant Republican majorities in both the House and the Senate and a Republican president. During the throes of this more recent debate, patient and disease groups from across the country stood united in their near unanimous opposition to any new law or change in existing law that did not clearly and unequivocally protect patients with pre-existing conditions.

Yet, for all of the state and federal health care laws designed to protect patients (including provisions within the ACA), and for all of the overwhelming bipartisan support for patients, can we say today that the millions of people in America living with pre-existing medical conditions are secure? Can we say that patients with pre-existing conditions are assured access and are safe from abuse or discrimination? The answer is an emphatic “no.”

Two decades into the 21st century, Americans with chronic or life-threatening diseases still face discrimination. The good news is that not all discrimination is intentional or malicious. Sometimes discrimination is well-intentioned but based on insufficient or outdated information. An example includes recent efforts by school districts in several states to compel all students with type 1 diabetes in a given school district to attend the same school, with the idea being that school administrators and school nurses may be better equipped to “help” students in these collective settings. The problem, of course, is that removing students from the general population and placing them in a setting solely based on disease is segregation. These students become identified and categorized by their disease, rather than as young people who also happen to have a disease. While discrimination like this should not be taken lightly, it can usually be mitigated through education and some form of legal advocacy.

A much more conscious and insidious form of modern disease discrimination happens at the institutional level. The ACA prohibits insurers from dropping or denying coverage for people with pre-existing conditions. The law does not, however, prevent insurers from exploiting or creating loopholes to essentially do the same thing. In fact, many argue that it was the insurance industry’s strong and sophisticated lobbying efforts that created many of the loopholes now being exploited to the detriment of patients.

The modern methods of disease discrimination, propelled through these legal loopholes, are many and varied. The most common are those methods used to stop or limit access to doctor-recommended medical treatments. “Step therapy,” also known as “fail first” protocols, are one such tool widely exploited by insurance companies. With step therapy, insurers require that doctors prescribe the least expensive treatment or medication first, even when that treatment course is contrary to a doctor’s best judgement for treatment of a patient. Otherwise, the insurer will reject coverage. It is only upon failure of those initial treatments that doctors can move toward prescribing treatments and medications most suitable to the individual patient’s needs and condition. The insurer clearly benefits in this situation by avoiding, or at least delaying, the need to pay for more expensive treatments.

The problem is that many chronic diseases are both aggressive and regressive. They are aggressive in that diseases can and usually do advance quickly in severity, and regressive in that the damage caused by many of these diseases is irreversible. Diseases like multiple sclerosis, lupus, Crohn’s, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis all fall into this aggressive/regressive category, and patients with these diseases (and countless others) are increasingly stuck in step therapy protocols.

Another loophole-driven impediment to access includes artificial financial restrictions. Given the growing cost of health care for all individuals, which is even more pronounced for those living with chronic conditions, many patients must rely on charitable assistance to help pay for their premiums, co-pays and deductibles. There is a longstanding tradition for this in the United States, with support typically provided by charitable nonprofits, church groups, veterans organizations, tribal associations and others.

The well-known Ryan White HIV/AIDS Foundation, formed to provide resources and support for patients and families suffering from HIV and AIDS, is an example of one such charitable support group. Yet insurers, once again, have attempted to exploit loopholes in the ACA to make it more difficult for nonprofit groups to provide, and for patients to utilize, charitable support. The effect of these polices, felt most profoundly by low-income and minority patients with immune system disorders, hemophilia rare diseases and kidney failure, are limits to treatment choices and access, forcing patients into narrower plan options or taxpayer-funded coverage.

To use an overused analogy, it’s an arms race. Insurers look for unique and sophisticated ways to lower their costs through access restrictions. Legislators and policy makers generally look to enhance access, but the process is slow and inefficient, often resulting in a hodgepodge of state and federal rules and gaps in patient protections.

All of this speaks to the need for new models and new initiatives for patient advocacy. Individual patients and patient groups, caught between health insurers and health care policy makers, must be strategic and increasingly sophisticated in their ongoing efforts to ensure full and affordable access to care. Leveraging patient advocacy groups, patient education and mobilization, social and earned media, coalitions and legislative outreach has never been more important.

Generating community conversations: Chronic Disease Day

Luckily, strategic and sophisticated efforts to stand up for patients do not have to be expensive or overly complicated.

When crafting awareness campaigns in the past, many people looked toward models that were highly visible, required large budgets and were intended to solve an issue at the national issue. We have now learned that this approach can paralyze organizers, often preventing or impeding the development and launch of effective campaigns. A better approach, especially in our hyper-connected world, is to start small and start local.

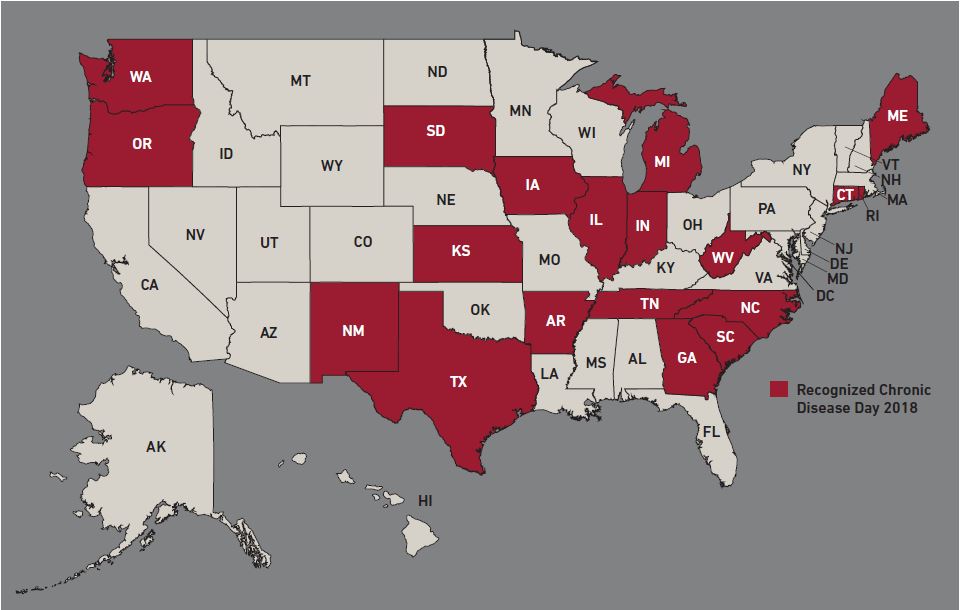

Each year, patients, providers, families and organizations (including ours) recognize Chronic Disease Day. The date, July 10 (or “7/10”), represents the seven out of 10 individuals in the United States who battle chronic conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, cancer, psoriasis and countless others. Importantly, Chronic Disease Day brings together thousands of patients, family members and friends to discuss challenges patients face when accessing care and tools that help to prevent or manage chronic disease, improve outcomes and lower overall health care costs.

While this effort was initially launched through the work of Texas-based Good Days, an organization dedicated to helping patients overcome financial barriers to care, it is only possible with the support of thousands of individuals in communities across the country. Organizations like Good Days and our own work to elevate a patient’s voice by providing them with the resources, information and support necessary to generate a community conversation around the impacts of chronic disease, while also empowering those individual patients to share personal stories and develop solutions that make health care more accessible.

Last year, over 15 states and cities recognized Chronic Disease Day, making it the largest effort yet. Armed with resources and information, advocates launched discussions in their communities both online and in person. For some participants, like Kristin Klontz, this day is confirmation that they are part of a larger disease community.

“It’s national #chronicdiseaseday and I want to give a shout out to all my fellow #ChronicIllnessWarriors!” wrote Klontz, an Oklahoma mom who battles lupus, on Twitter last year. “Battling lifelong illness is the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I’ve been through some stuff! But, together we are stronger #chronictogether.”

Building a network to support civic engagement: Ambassador Program

While one person can spark a conversation, a group effort can best ensure the dialogue has a lasting, measurable impact.

Every day, organizations like ours hear from patients who have faced significant hurdles while trying to access care. One example is attorney and patient advocate Jim Myers of Indiana, who battles polycystic kidney disease, an inherited form of kidney failure.

For several decades, Myers has experienced and witnessed discrimination at the hands of the insurance industry, particularly as it relates to a patient’s ability to access charitable financial assistance to afford their health insurance. There is no cure for kidney failure. Instead, patients must undergo dialysis treatments to filter toxins from their blood several times each week to survive. Due to the financial and physical severity of this treatment, patients with kidney failure are eligible for Medicare before the age of 65. In part because Medicare comes with high out-of-pocket expenses for these patients, many purchase commercial insurance plans or private supplemental health plans to manage these costs.

Unfortunately, the insurance industry often targets people with this life-threatening disease, particularly those who rely on assistance from charities to pay their monthly health insurance premiums, by denying these charitable payments. In effect, the patient is either left to pay their expensive insurance premium out of their own pocket or lose their health care coverage. Why do insurers do this? It’s simple: Insurers want to avoid the expense of chronic disease patients and legal loopholes, at the state and federal level, often allow them to do so.

These experiences are all too familiar for Myers and countless other patients. While Myers and many other patients had shared their stories and raised awareness about these issues in their local communities, they were interested in collaborating and taking actionable steps to improve access to affordable, quality health care. The Chronic Disease Coalition’s Ambassador program was born out of this necessity.

This program, and others like it, provides the foundation and network essential for various types of civic engagement practices: Hosting forums, conferences and community meetings, providing resources to address unmet community needs and organizing to elicit policy changes.

When frustrated by the lack of education some doctors seemed to have around endometriosis, in just one example, three of these ambassadors came together with an objective. They wanted to decrease the delay between a patient’s initial onset of symptoms and the final diagnosis, which often ranges from three to 11 years, according to the National Institutes of Health, while also educating doctors about the patient experience.

Together, these three ambassadors developed a first-of-its-kind educational program. Under their leadership, they mobilized additional patients within the endometriosis community to support the curriculum and conduct outreach to providers to have them participate in this educational program. To date, they have confirmed participation in this program with nearly a dozen providers – a major success in a short period of time that may not have been possible without this new model for teamwork and collective grassroots action.

Empowering patients to create policy change: Living Donor Protection Act

Once awareness has been generated about an issue and a foundation for support has been built, patient advocates have a framework for successfully tackling larger issues.

This year, for example, the Chronic Disease Coalition led a patient-centered campaign in Oregon to establish protections for people interested in giving the gift of life by becoming living organ donors. Nearly 114,000 people in the United States are waiting for a lifesaving organ transplant, and 22 people die every day while on the waiting list. Not only does living organ donation decrease the wait time; organs from living donors also tend to survive longer in their new environment and result in fewer complications post-transplant.

Despite these benefits, many people are discouraged from donating for fear of losing their job while taking the time off work to donate and recover. In addition, once they have donated an organ, a perfectly healthy individual inherits a “pre-existing condition,” and may be subjected to higher health insurance premiums or have difficulty obtaining long-term care and life insurance.

With this knowledge in hand, we reached out to possible partners in the community – patients, donors, organizations and more. Together, we convened a large group of stakeholders and began outlining language that would protect future donors from workplace and insurance discrimination. In a matter of weeks, we had a drafted bill.

Moving policy through a state legislature can be a long and laborious process, but it’s made easier with the help of advocates. It’s important to know the “why” behind a cause or bill, and legislators want to hear this from those that are directly impacted in their community. With the help of patients, donors and families, we conducted outreach to key legislative offices and participated in hearings. These personal stories, engagement with legislators and recognition of the issue ultimately led the bill to pass almost unanimously through both chambers. It now awaits signature on the governor’s desk.

Big challenges, bigger hopes

The majority of adults living in the United States have at least one chronic disease or pre-existing condition, and this number is only projected to grow as our population ages. As health care costs continue to rise, insurers are increasingly looking for ways to decrease costs, often to the detriment of patients. A single organization like ours cannot directly interact with every patient in need or take on every important patient discrimination issue.

Still, we are hopeful that the growing set of available tools and techniques, combined with growing public awareness, will help patients and patient advocates everywhere organize to secure better outcomes. Through the civic engagement processes, patient advocates can educate, empower and mobilize others to create the needed changes that will positively impact our communities for years to come.

Scott Bruun, a former state legislator and long-time diabetes advocate, is executive director of the Chronic Disease Coalition. The Chronic Disease Coalition is a is a national 501(c)(6) non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring patients have access to quality, affordable care by exposing and addressing discriminatory practices and policies that create access barriers.