John Gastil

Different municipalities call themselves the heart of Silicon Valley, but the City of San José has the most valid claim. Smaller communities, such as Mountain View and Cupertino, have outsized roles in the valley’s history, but San José stands out as the major metropolitan hub.

The upside of being a tech hub is an ability to attract new development, such as the Google campus that will land near downtown before too long. The downsides are numerous. Digital technology jobs, for example, have driven up the cost of housing to the point that a family of four counts as “low-income” if it pulls in less than $85,000 a year.

More subtle are the expectations that come with wearing the dot.com crown. While standing at the sink in the San José airport, I heard a traveler curse: “You’d think they’d have figured out paper towel dispensers in the [expletive] Silicon Valley!”

This is more than an anecdote. An airport administrator confirmed that visitors and residents alike believe that the city’s facilities should showcase the cutting edge of digital technology. As soon as their plane touches down, passengers expect to be placing online orders at the airport café. Is such an app on its way? “Soon,” the official confided, “but not quite yet.”

I heard that refrain more than once during the four months I spent with the San José Office of Civic Innovation. Overseen by Deputy City Manager Kip Harkness, this office follows an ambitious roadmap for improving city operations. This roadmap includes everything from setting up public broadband to monitoring traffic flow and streamlining hiring procedures.

The office prioritizes projects with the biggest near-term impact, but Harkness asked me to join his team as a volunteer to help it imagine bigger changes yet to come. Meanwhile, my position as communication professor at Penn State afforded me a sabbatical year to launch a longitudinal study of online public engagement. Where better to begin such a project than the heart of the Silicon Valley?

A Shared Vision for Digital Engagement

Harkness first saw my argument about civic engagement in a white paper, which argued for building a “Democracy Machine” to reconnect citizens with public officials. The title was tongue-in-cheek, but the idea was serious.

In the U.S., we have yet to build—at any level of government—a robust online public sphere. From the earliest days of the Internet, civic innovators have dreamed of digital democracy, but the private sector has outpaced public investment in civic tech. The most ambitious private ventures to date (Brigade, iCitizen, and NationBuilder) aim to replicate partisan dynamics online, and the most visible nonpartisan sites either rely on a single philanthropist (Ballotpedia) or have chronic funding problems (Project Vote Smart).

A sustainable, deliberative, and non-commercial digital public sphere remains attainable in the U.S., but without active intervention by government and nonprofit organizations, we are more likely to become reliant on privately curated and inegalitarian public spaces.

As an alternative, I propose creating an interlinked system to exchange data across different public services and civic sites. This would not entail building a new platform. Rather, it would make existing (and future) tools interoperable and sustain their ongoing development through public funding. In this system, citizens would have the ability to move easily between civic games, prediction markets, deliberative surveys, and discussion forums because the system would connect each of those tools in a more intuitive way. Just as a Facebook identity seamlessly links data and services within and beyond that particular platform, so could a unique identifier do the same for a person’s civic experiences online. This linkage would introduce a privacy challenge akin to digital health records. Access control would need to be nuanced and granular at a level that grants users full control over their own data, which could foster heightened digital literacy and training for lay citizens.

To see how this would work, consider this scenario: In an integrated digital commons, your career as an engaged citizen might start with a few clicks on a mobile device. Spotting and reporting illegal dumping on a city street prompts an invitation to brainstorm on improving the city’s waste disposal system. That draws you into a chat on urban planning priorities, where you get to talk with city officials. You end up collaborating with fellow residents, who you met through these events, to draft a petition to revitalize a neighborhood park. All the while, your local government keeps acknowledging your suggestions, noting when problems get addressed, and offering thoughtful explanations when it cannot act on your advice.

Effective Engagement on a Google Development

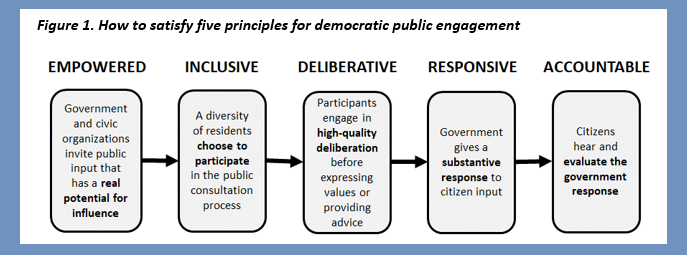

That example may sound like science fiction, but it illustrates core principles for public engagement that resonate with anyone working in government or civic reform. Figure 1 summarizes these principles and shows their sequence as part of a system of public consultation that is empowered, inclusive, deliberative, responsive, and accountable.

To give these abstract principles a more concrete meaning, I will place them in a specific context. Earlier this year, the San José City Council voted unanimously to approve selling nine publicly owned parcels to Google for $67 million. The land stretches along the Guadalupe River west of downtown and surrounds Diridon Station, the city’s regional transit hub.

Landing this “Google campus” was a huge public relations victory for Mayor Sam Liccardo. He could point to survey data and strong public support for a development that promised to bring in 20,000 jobs and raise the global profile of the city. Even so, the mayor chose not to mention the project in his 2017 State of the City address, while activists repeatedly disrupted his remarks and held a quieter vigil outside the auditorium to protest the looming arrival of “Googleville.”

Both the mayor and city manager recognized the need for public engagement on the Google development, and at considerable expense, city officials convened the (Diridon) Station Area Advisory Group (SAAG) as a primary means of gathering community input. The advisory body’s basic design aspires to satisfy five principles for effective engagement, but it can also show how the city could go farther in its future consultation via digital augmentations.

Turning to the first of the five principles, the members of the advisory group needed to be empowered to count as a democratic form of engagement. Democracy is about self-government, and the point of such a body is to give citizens a strong enough voice that they can have an impact on policy. In this case, the city authorized the advisory group to write what amounts to a community impact statement that highlights pressing needs that the Google campus might help address, along with problems it should take care not to exacerbate. By giving the SAAG the power to present a formal report to the council, the city gave it a modest chance to influence council and agencies, as they work out the details of the development with Google.

Second, the advisory group is an inclusive body in that it brings together a diversity of stakeholders—business leaders, community activists, civic organization officers, and lay residents with recent experience in public consultation. It is a credit to the city that it had little trouble recruiting participants for the board, and it has tried to keep the board accessible to a wider audience by holding the board’s principal meetings on weekday evenings, broadcasting its proceedings, and making available to the public the materials board members receive.

Third, the advisory board uses procedures to improve its face-to-face discussions, and it has a wider plan for sparking at least some citywide deliberation. For its public meetings, the board uses a team of facilitators, a clear turn-taking procedure, and sensible discussion norms that its members have followed in the sessions I observed. More important is the macro-level deliberation the board aims to promote by soliciting input from lay citizens through walking tours of the development site, open houses showing plans, plus focus groups and surveys with more representative cross-sections of the city.

Fourth, when the board wraps up its work, it should elicit a formal response from the city council, though this has not been spelled out in its charter. The mayor and others will likely have a reply to the board’s report, but the responsiveness principle stresses that these replies address directly whatever points come through in the report. Governments often fall short at this stage by giving responses that offer praise without directly addressing the trickiest bits of public input. The idea is not to accept such input without qualification but rather to clarify what suggestions can be implemented, which require study (and for how long), and which are infeasible or undesirable (and for what reasons).

The final step appears rarely in public engagement schemes, but it is the key to creating a solid feedback loop between the city and its residents. Ideally, after the advisory group would present its findings and elicit a response, the members of that group—along with a wider cross-section of San José residents—should have a meaningful opportunity to evaluate the city’s reply. That is not built into the current plan, but nothing prevents its addition in the future.

Digital Enhancements to Conventional Engagement

The San José Office of Civic Innovation does not oversee the Station Area Advisory Group, nor did I have a role in shaping its design. Even so, during the time I spent with the innovation team in City Hall, I discovered many ways the city could enhance its future public consultations using tools it already has in development.

In the long-run, this could lead to a full-fledged system for ongoing public consultation and civic engagement, but I will try to show the more incremental steps the city could take in the short-term toward such a system. Each of these steps improves existing outreach methods by better satisfying the five principles of democratic public engagement that I have enumerated.

Incident Reporting as a Gateway to Deeper Engagement

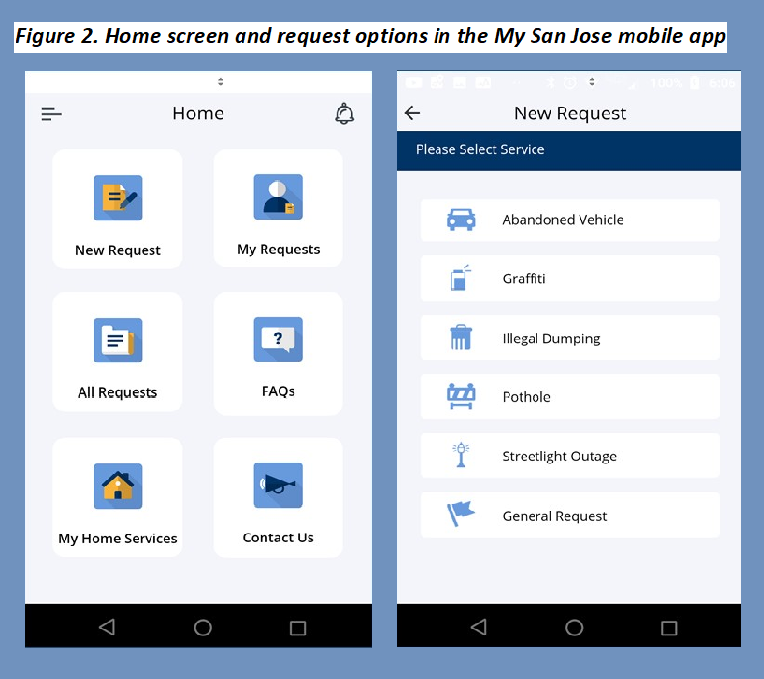

The most visible move the city has made into digital engagement is the My San Jose app. Cities around the globe have experimented with mobile tools, and San José opted to create its own custom interface. Figure 2 shows the app’s main functions, along with a list of the six options residents have for making direct requests. If a resident sees graffiti, a pothole, or anything of concern, the app makes it easy to route a photo and textual details to the right office. The city, in turn, can respond quickly—often to acknowledge the request before taking action. Residents can then use the app to see what’s in the queue, including submissions from other users who have logged incidents across the city.

The My San Jose app permits anonymous incident reporting, but to make it a more powerful tool for long-term engagement, the city could revise its interface to emphasize the importance of providing a reply email address. Without that, My San Jose has no feedback loop, which limits its potency. An anonymous option is useful, to be sure, but it should be available only for those who consciously intend to opt-out of further communication.

For those users who do provide contact information, the city began in May to close the feedback loop by asking, essentially, “How did we do?” That alone will help discern whether using My San Jose gives residents a satisfactory experience. Soon, the city will improve that feedback survey. For instance, the city could measure changes in residents’ broader confidence in the city and in themselves as active participants in governance. Over time, those indicators could rise as a direct result of the city’s responsiveness to specific resident concerns.

If this modest customer feedback loop does its job, this app could draw people into more intensive future activities on behalf of their city. Let’s say that there are three types of My San Jose users: one-timers (who lodge a single complaint but have no interest in community engagement), the nearly-active (who see the app as an easy way to help their community) and engaged residents (who already have a repertoire of regular civic activities). If My San Jose asks permission to follow up with users at a later date, a large share of those in the second and third categories might assent. The next time a consultation opportunity like the Station Area Advisory Group comes around, the city should have a large and expanding contact list at the ready.

Annual Surveys as Recruitment Tools and Accountability Mechanisms

Whether the residents who lodge complaints online embrace further engagement remains to be seen, but regardless, the city needs to augment app-based recruitment with one that reaches a greater diversity of residents. After all, those who make the effort to report abandoned vehicles and streetlight outages are a particular subgroup of the city’s residents.

There is no substitute for using random samples and targeted recruitment to ensure that the city hears from a broader cross section of the community—especially underrepresented neighborhoods. It might appear that such sampling and recruitment would put undue strain on a tight city budget.

On closer inspection, however, city offices regularly contact large numbers of residents through public meetings, correspondence, and surveys. Each of those are missed opportunities for recruitment into a broader citywide database of interested and active residents who might be called on for input on new projects, such as the Google campus, or any number of difficult issues a city must tackle.

In the case of San José, the auditor’s office could prove one place to start such an effort. City Auditor Sharon Erickson and her staff invited me to examine their annual resident satisfaction survey to explore ideas for future research. Like many of her peers across the U.S., Erickson participates in the National Citizen Survey (NCS). The NCS uses a standardized methodology for assessing residents’ attitudes toward a city, its departments, and its services. In 2017, Erickson authorized the collection of community surveys from both a random mail sample and an opt-in online portal.

Until demographic weights were applied to the NCS data, neither the random sample nor the opt-in survey approximated the city’s complex demographics. In the Census Bureau’s 2016 American Community Survey, for example, 34 percent of San José residents identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, 33 percent as Hispanic, and 27 percent as White, non-Hispanic. By contrast, the plurality (45 percent) of the unweighted random sample identified as White, non-Hispanic, as did more than two thirds (68 percent) of the opt-in sample. In creating the main data file for San José, NCS statisticians reweighted each respondent such that the distribution came closer to census figures. Even so, that rejiggering had to simultaneously rebalance multiple variables, and in the end, the White population remained overrepresented.

The most obvious solution to this sampling problem is often cost prohibitive. The National Opinion Research Center and other large organizations have the means to collect representative samples, but the rigor of their methods requires expending resources unavailable to even a city as large and prosperous as San José.

An alternative approach doubles down on the opt-in survey by augmenting it with more respondents, drawn to the online survey portal via targeted recruitment in underrepresented communities. In San José, this means crossing language barriers. A majority of residents speak a language other than English at home. Thus, targeted recruitment means reaching out to neighborhoods such as East San José, where Spanish is the primary language in nearly 70 percent of some housing tracts. Another 10 percent of the city’s households speak Vietnamese at home, and the city already translates its NCS survey into these languages.

The annual survey provides a special opportunity to reach these communities because it gives respondents a chance to have their voices heard through the auditor’s official assessment. Most mail, phone, and Internet surveys have a more diffuse purpose, such as soliciting an opinion on one topic or another, with no promise of public reporting. Some of those surveys, including ones commissioned by nervous elected officials, have a transparent political purpose. This makes busy residents reluctant to give even a few minutes of their time.

Officials might fear that residents opting to complete the auditor’s survey would use it as a chance to vent. In the 2017 San José weighted results, for example, 48 percent of the random sample gave good/excellent ratings to city services, compared to 39 percent of the opt-in sample. The gaps weren’t always this large: again using demographic weights, 59 percent of those contacted at random rated San José as a good/excellent place to live, with a similar figure (54 percent) appearing in the opt-in sample.

Even if expanding the opt-in response pool elicits negative input, doing so has an upside. It demonstrates the city’s willingness to hear tough feedback and hold itself accountable. Such a city wants to serve empowered residents who know their opinions count. This can be done in the name of inclusion, even if the city can only afford an online survey portal that limits its reach to respondents completing surveys at computer terminals at home, public libraries, or community service centers.

Empowered Deliberation

As with the My San Jose app, every respondent to this survey could be invited to participate in future outreach activities. Building a growing database of concerned residents through the My San Jose app and the annual survey, however, amounts to a promise that must be fulfilled. Every time a resident marks a checkbox for further contact, a clock starts ticking. The city needs to have a plan not just for occasional consultations but for ongoing activities to provide a new opportunity for residents eager to say more. If residents get invited to participate in unspecified future activities but none appear, it can leave them feeling more alienated from their government rather than more closely connected.

Fortunately, San José has taken steps toward moving online its most intensive outreach methods. The city has experimented with participatory budgeting, and although these have mostly occurred in face-to-face events, a local software developer has helped move some of this process online. Conteneo CEO Luke Hohmann has used his company and the Every Voice Engaged Foundation to help residents grapple with budgetary and policy tradeoffs. Though San José has only begun to test the efficacy of such tools, its use of them may accelerate as officials welcome public input on the thorniest questions it faces.

To consider how this might work, let’s return to the example of the Google campus development. After the Station Area Advisory Group identifies its chief concerns, it could present those to a larger and more diverse cross-section of the resident database built through the city’s app and its various surveys. Participants would meet in small online groups to weigh alternative choices and their tradeoffs, with an eye toward seeking common ground. For precisely such purposes, Hohmann partnered with the Kettering Foundation’s digital program officer, Amy Lee, to build the Common Ground for Action (CGA) interface.

Loosely based on the National Issues Forums Institute’s public discussion program, CGA is a highly structured online deliberative forum in which four-to-eight citizens meet for one or two hours to talk through a challenging policy issue. Graphics generated in real time by the users themselves show the shifting shape of a discussion group’s common ground. By sharing personal stories and experiences, assessing three-to-four options rooted in values, and reflecting on the advantages and tradeoffs of a larger list of potential actions, the forums help participants discover where they can agree to move forward.

The surveys I have conducted after these CGA forums show that participants usually find them both challenging and satisfying. More importantly for the city, CGA forums consistently reveal more than aggregated individual judgments. Instead, they discover clear areas of common ground, reached through discussion, along with the finer points of disagreement that remain after considering the tradeoffs among alternative policy solutions.

To see how San José can use a tool like CGA, consider digital privacy—an issue the city faces that involves non-obvious tradeoffs. If the city refrains from collecting and storing resident email addresses, this helps keep such information private—unreachable by careless city employees or unscrupulous actors who might hack into a city database. On the other hand, residents want timely warnings when there are public safety hazards, such as the flood that caught many residents off guard in 2017.

Beyond such emergencies, residents may want to stay connected to their government—and give up that small bit of privacy—for other reasons. They may want to hear directly from the city when it considers development projects and other policies that would have a direct impact on their lives, and they don’t want the city spending exorbitant amounts of money on public outreach, such as mass mailings and media buys.

The Office of Civic Innovation is investigating public attitudes around this issue because it wants to establish a city policy that balances the need for privacy with the direct benefits and system-wide efficiencies integrated data can provide. Ideally, the city could elicit informed judgments after drawing residents into deliberation through an interface such as the CGA.

At a minimum, the city could commission a deliberative survey that works through concrete scenarios, such as an imminent flood or a proposed rezoning, which lay out real tradeoffs that residents can understand. Such a survey would ask residents where to strike a balance between two or more values they hold, for instance, safety and privacy. Answers to these questions could be followed by prompts that underscore tradeoffs, as in “remember that if you get more X, you get less Y,” to test the robustness of respondents’ judgments.

Engagement for the Long Term

As I argued earlier, the point of these interventions—the app, surveys, and online discussions—is not to elicit more one-way input but to establish a feedback loop. The city will succeed in integrating these tools only if it follows up the input it receives, gives substantive responses to residents’ observations and policy advice, then gives them a chance to evaluate that response.

Once again, this requires a modicum of courage on the part of public officials. The faint of heart will be pleased to learn that exposing a city to scrutiny can boost public trust. Harvard Business School professor Ryan Buell made this argument in a 2017 white paper, which shows what happens when governments show residents how a city works and invite them to understand its challenges. Buell and his colleagues call this “surfacing the submerged state.” A series of experiments they undertook in Boston suggest that ongoing engagement can improve residents’ attitudes toward public officials by drawing the public and its government closer to one another.

In this regard, San José is on the right trajectory. After reviewing the city’s engagement toolkit and officials’ aspirations, I independently reached the same conclusion as staff in the mayor’s office—that the future may be a personalized “digital dashboard” for residents and city officials. On such a site, residents can see new opportunities to speak up, as well as evolving city responses to past engagements. Officials can see live public feedback and respond directly to engaged communities, whose input is channeled through deliberative processes.

If implemented thoughtfully, this should streamline the city’s outreach efforts, rather than creating a new administrative burden. If connected with the social media tools residents are already using, this could make their engagement easier and more rewarding for residents as well.

All this may happen soon in San José, but not quite yet. Even so, the time has come for conducting real experiments with the tools at hand to see how far they can take cities willing to innovate.

John Gastil is a professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and Political Science at Pennsylvania State University and a Senior Scholar at the McCourtney Institute for Democracy.

Further Reading

Buell, Ryan, Ethan Porter, and Michael Norton. 2017. Surfacing the submerged state: Operational transparency increases trust in and engagement with government. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper 14-034.

Dubow, Talitha, Axelle Devaux, Christian Van Stolk, and Catriona Manville. 2017. Civic engagement: How can digital technologies underpin citizen-powered democracy? Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation and Corsham Institute.

Gastil, John. 2016. Building a Democracy Machine: Toward an integrated and empowered form of civic engagement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School of Government. (available online)

Gastil, John, and Sascha D. Meinrath. 2018. “Citizens and policymakers together online: Imagining the possibilities and taking stock of privacy and transparency hazards.” Computer 51(6): 30–40.

Gordon, Eric, and Paul Mihailidis (eds.). 2016. Civic media: Technology, design, practice. MIT Press.

Howard, Philip N. 2015. Pax technica: How the Internet of Things may set us free or lock us up. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Noveck, Beth Simone. 2015. Smart citizens, smarter state: The technologies of expertise and the future of governing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sandoval-Almazán, Rodrigo, J. Ramon Gil-Garcia, Luis F. Luna-Reyes, Dolores E. Luna, et al. 2012. “Open government 2.0: citizen empowerment through open data, web and mobile apps.” In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, pp. 30–33.