By Mike McGrath

How can city managers facilitate the creation of deliberative, civic spaces where citizens can learn and work in more democratic and complementary ways? This was one of the questions a group of local government managers were asked to explore during a “learning exchange” at the Charles F. Kettering Foundation in Dayton, Ohio last November.

An operating research organization, the Kettering Foundation regularly holds these day-and-half conversations with members of community groups, civic associations, professions or institutions who are experimenting with different ways of strengthening democracy.

The November exchange with public managers began with a screening of a stop-motion, animated video, “The Parable of the Blobs and Squares,” narrated by the British actor Brian Blessed, whose sonorous voice would be immediately familiar to anyone old enough to remember the BBC-TV adaptation of the historical novel, I Claudius.

The “squares” were the institutional players, the government managers and nonprofit sector employees tasked with addressing difficult community challenges. These institutional players were accountable to the public for the ways they spent money, so they tended to “count stuff and measure stuff” and arrange things in an orderly fashion. But the problems they were trying to solve weren’t square. They were more “blobbish” and could not be fit into neatly arranged square packages.

So, the government squares went to the nonprofit squares with experience working with blob people, that is, the nonexpert citizens, who were closest to the blob-like problems, to better understand the nature of those challenges. In the process of doing this, however, the squares asked the blobs to write reports, attend training sessions and provide needs assessments.

In time, the report-writing blobs began to resemble the squares, thus losing the attributes that made them blobs in the first place, “their energy, grassroots connections and vitality.” But there was another way of working, “co-production.” With co-production the squares brought what they could contribute, the expertise, and the blobs provided what they understood, the context, and both contributions were equally valued.

The video was intended as a cautionary tale for well-meaning public managers, nonprofit groups and elected officials who embrace the idea of civic engagement or public participation as a strategy for building trust, gaining public support and harnessing the collective wisdom of the communities where they work. Even with the best of intentions, working with the public is a complicated business that can often fall short or even have unintended consequences.

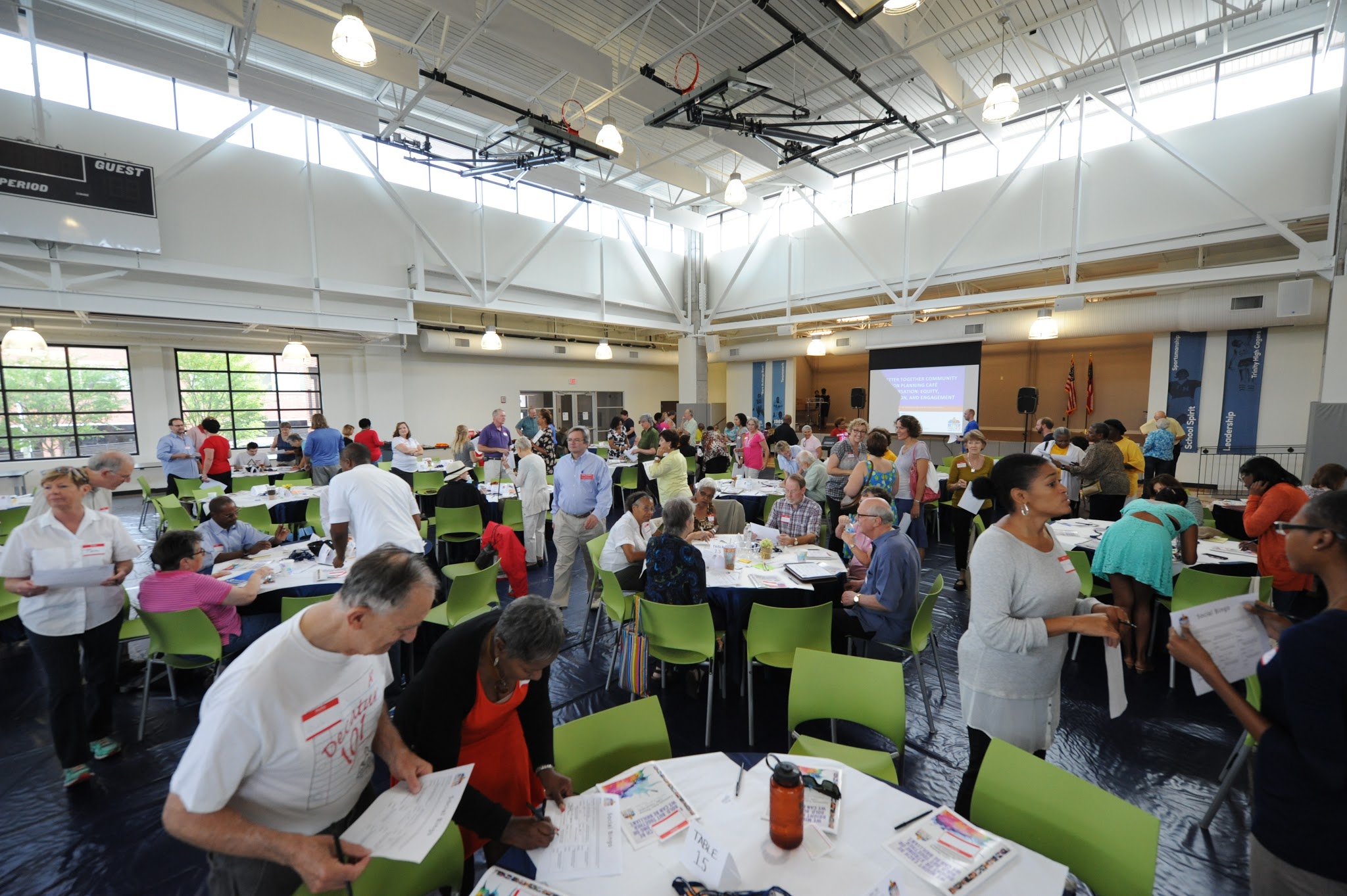

Among the participants were city managers, retired city managers, assistant city managers, deputy city managers, county managers and assistant county managers. Also participating were departmental staff, Kettering program officers, research associates and representatives of nonprofit groups such as the National Civic League that promote public engagement, democratic governance or community development.

The managers described a variety of innovations designed to build trust and engage a diverse cross-section for their communities. In one small city, the manager organized a “super hero-themed connection forum” to identify local civic leaders. More than 150 people attended, half of them appearing in the costume of their favorite super heroes.

The growing influence of technology and social media was a recurring topic of concern and interest for these public managers. For instance, one deputy city manager was tasked with looking for ways to work with the developers of social media apps to map out emergency response information during natural or manmade disasters. The effort, he suggested, was an opportunity to engage residents in new ways.

Others worried that an over-reliance on social media could undercut the face-to-face interactions that are necessary for real civic engagement to thrive. “We’re losing some of what has made the community special as more and more people opt for technology,” she said, asking, “Is our job to give people what they want, which is online platforms, or creating engagement?”

One manager spoke of using social media as a means of understanding what is going on in the community, rather than as an engagement tool per se. In his city local officials discovered a trend on social media sites—a concern over a local code enforcement issue. Seeing that the problems were out there, city staff members were able to sit down with members of the community and allay the concern.

In one city, managers were alerted by social media posts to the fact that their placement of a traffic light on one residential street had not gone well. “Commutes that would have been five minutes turned into 45 minutes,” said an assistant city manager. “When we saw the comment, we issued an apology to the community through every forum, Facebook and on our website, where we could get it out. We have spare use of social media. Less is more, the trick is knowing the right time to jump in.”

The exchanges have explored various facets of a central question that is of deep interest to both the Kettering Foundation and the National Civic League: how do public managers align their ways of working with the residents of their towns, cities and counties? As one former city manager pointed out during the most recent learning exchange, managers should not think of themselves as the “sole solution providers.” The “wicked problems” that defy technical solutions, “cannot be solved by government alone,” she said, “but the manager and staff can be a facilitative tool and get them into a space where they can talk about what we all need to solve these problems.”

The Kettering Foundation and Public Deliberation

Incorporated in 1927, the Charles F. Kettering Foundation began as a general philanthropic organization with funding priorities that reflected the interests of its founder, a prolific inventor who revolutionized the auto industry by designing the first self-starter and served as head of the research laboratory at General Motors. A champion of collaborative, interdisciplinary research teams, Kettering’s ideas about innovation and invention continue to influence the work of the foundation today.

After Kettering died in 1958, the mission of the foundation began to expand. During the 1960s and 1970s, the foundation had groundbreaking research programs on education reform, urban policy and citizen diplomacy. Over time, however, the foundation’s approach to problem-solving and democracy began to change from its focus on policy and strategy to an emphasis on public deliberation and what Kettering President David Mathews describes as “community politics.”

Drawing on classical democratic theory as well as more modern thinkers such as John Dewey, Hannah Arendt, Jürgen Habermas, and Elinor Ostrom, the foundation developed a series of ideas about citizens came together to address community problems. Community politics puts citizens at the center of public problem-solving and democratic governance.

Rethinking the Role of Professional Manager

The profession of city manager was “invented” in the early twentieth century as part of a municipal reform package designed to improve management practices, eliminate structural inefficiencies and discourage the widespread practice of graft, corruption and patronage.

The U.S. Constitution was silent on the question of how cities should be governed, so in the absence of any models, municipal reformers set out to create a new one. The model that emerged was partly based on the modern corporation. The city council was like the board of directors, and the city manager served the role of corporate executive.

As it happened, the first major urban municipality to accept the new model was Dayton, Ohio, home of the Kettering Foundation. Before the change, however, Dayton’s partisan government was thought to be ineffectual, the city deeply in debt. The new model seemed to offer a more competent future.

The city improved its health department with free nursing and medical inspection. Parks and playgrounds were upgraded. Outside experts were consulted to deal with everything from traffic management to sewer maintenance. A nonpartisan civil service commission was established, along with citizen advisory boards. The city’s budget deficit was eliminated.

Professionalism and expertise, however, did not solve all of Dayton’s problems. By the early 1960s, the city was facing the same set of vexing challenges found in other major urban centers, a deindustrializing economy, job and population loss from suburban flight, high crime and unemployment rates, poorly performing schools and growing racial tensions.

Dayton leaders responded to these challenges by enacting new set of reforms, including the creation of an office of ombudsman and a system of priority boards to ensure greater levels of citizen participation in problem solving and decision-making. Other communities began to experiment with similar innovations.

Fort Wayne, Indiana, for example, opted for a decentralized administrative system known as “Community Oriented Government.” Los Angeles developed a formal structure of neighborhood councils. Seattle experimented with neighborhood-generated capital improvement projects. Sarasota County, Florida created a nonprofit organization to sponsor regular citizen dialogues about pressing local issues.

These experiments reflected a growing recognition that the challenges facing communities were so complex and the policy choices so value-laden and contentious, that forming a workable consensus required a more rigorous approach to public engagement than the usual practice of saving thirty minutes on the council or zoning commission agenda for “public comment” at the end of a long meeting. City managers began to see their roles as more than experts and technical problem-solvers. They were also facilitators, conveners and participants in an open-ended conversation about the future of their communities.

These experiments reflected a growing recognition that the challenges facing communities were so complex and the policy choices so value-laden and contentious, that forming a workable consensus required a more rigorous approach to public engagement than the usual practice of saving thirty minutes on the council or zoning commission agenda for “public comment” at the end of a long meeting. City managers began to see their roles as more than experts and technical problem-solvers. They were also facilitators, conveners and participants in an open-ended conversation about the future of their communities.

“Local governments across the country and around the world are moving beyond the typical emphasis on voting and the ‘public comment’ hearings of the past toward finding effective ways to get citizens involved and working to foster civic culture and infrastructure,” note James Svara and Janet Denhardt in a whitepaper for the Alliance for Innovation. “These efforts require a great deal of creativity, energy and commitment to succeed, but the effort appears to be worth it: research has shown that effective citizen engagement can foster a sense of community, engender trust, enhance creative problem solving, and even increase the likelihood that citizens will support financial investments in community projects.”1

Wicked Problems

One of the helpful concepts that participants in the Kettering learning exchanges have been exploring is the idea of “wicked problems,” that is, the problems that defy technical solutions and top-down administrative approaches to decision-making. The term was coined by urban planning professors at the University of California, Berkeley, Horst W. J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, in the early 1970s, a time of declining trust in public institutions.

The professional’s job, they wrote, had once been viewed as “solving an assortment of problems that appeared to be definable, understandable and consensual. He was hired to eliminate those conditions that predominant opinion judged undesirable. His record has been quite spectacular, of course; the contemporary city and contemporary urban society stand as clean evidences of professional. The streets have been paved, and roads now connect all places; houses shelter virtually everyone; the dread diseases are virtually gone; clean water is piped into nearly every building; sanitary sewers carry wastes from them; schools and hospitals serve virtually every district; and so on.”2

Technical approaches to problem-solving were not as successful in addressing complex societal problems for which there was no collective understanding of or agreement on the nature of the problem. Crime, for instance, could be viewed as “not enough police, too many criminals, by inadequate laws, too many police, cultural deprivation, deficient opportunity, too many guns,” etc.

Without an agreed upon definition of a problem, how could there be an obvious solution? What’s more, the growing diversity of communities meant that there was a plurality of “publics” pursuing an array of sometimes conflicting goals. How could a planner plan, when there is no agreement on the nature of the problem, much less a solution?

“Wicked problems have no technical solutions, primarily because they involve competing underlying values and paradoxes that require either tough choices between opposing goods or innovative ideas that can transcend the inherent tensions,” writes Martin Carcasson, founder and director of the Center for Public Deliberation at Colorado State University. “Addressing them well also often requires adaptive change—changes in behavior or culture from a broad range of potential actors—that neither the expert nor adversarial processes tend to support.”3

Public Deliberation

One way for people to make those adaptive changes was through a process of public deliberation. What some have described as the “deliberative democracy” movement grew out of critique of adversary democracy (Jane Mansbridge) and “weak” forms of democracy (Benjamin Barber). The Kettering Foundation was instrumental in creating the National Issues Forums, a network of facilitators and host that held regular deliberative forums on important national issues.

Another author whose ideas were highly influential was Daniel Yankelovich, a pioneer of public opinion research and a founder of Public Agenda, a nonprofit research and public engagement organization in New York City. In his book, Coming to Public Judgment, Yankelovich made a distinction between “public opinion,” the surface thoughts reflected in popular opinion polls, and “public judgment” a deeper and more meaningful understanding that “exists once people have engaged an issue, considered it from all sides, understood the choices it leads to, and accepted the full consequences of the choices they make.”

Public deliberation is a process in which groups of people with difference perspectives and experiences come together to talk through their ideas about policy choices and important public problems. The process of coming to public judgment through deliberation is as much about an examination of values and feelings as it is about facts or rational arguments.

Complementary Production

Elinor Ostrom was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize for Economics and author of the ground-breaking study, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. She and her husband, Vincent, conducted extensive research of the governance of finite natural resource systems, discovering that informal mechanisms for discouraging waste or overuse were often more effective than government regulation or management by private owners.

Ostrom also did research on local government agencies and the relationship between scale and effective service delivery. In looking at police departments in Southern California, for instance, she challenged the widespread assumption of experts that consolidating police services improved the delivery of public safety services. On the contrary, some of the smaller city police departments were more effective than consolidated departments. Police officers in these smaller forces could be more closely connected to members of the community.

She coined the phrase “co-production” to describe the ability of citizens to be directly involved in the provision of goods and services usually associated with governments. “Obviously skilled teachers, police officers, medical personnel, and social workers are essential to the development of better public services,” she wrote.

Ignoring the role of children, families, support groups, neighborhood associations, and churches in the production of these services means, however, that only a portion of the inputs to these processes are taken into account in the way that policy makers think about these problems. The term ‘client’ is used more and more frequently to refer to those who should be viewed as essential co-producers of their own education, safety, health and communities. A client is a name for a passive role. Being a co-producer makes one an active partner.4

Kettering has taken the idea of co-production and adapted it to its ideas about community politics. “Complementary production” is a related but slightly different concept. Complementary production is when citizens develop their own initiatives to accomplish tasks or goals that government or formal nonprofit organizations can’t do. The impetus for initiating these projects does not come from government or some formal nonprofit organization, but these more spontaneous or autonomous efforts may serve to complement the work that government officials or nonprofit professionals are already doing.

A Learning Community

Most, if not all, of the public managers who have participated in the Kettering learning exchanges are seeking new and innovative ways of putting grassroots democracy and public participation are front and center in the policy-making, planning and problem-solving efforts of their cities, counties and departments.

Seeing civic engagement or public participation as a process or set of procedures that can be implemented through public projects or permanent structures such as neighborhood councils or priority boards, however, can raise a new set of questions about the role of citizens in communities. These structures can be invaluable. They can foster a culture of engagement in a community, especially when they are well-facilitated, well-attended and conducted or maintained over a lengthy period of time. They provide civic spaces for citizens to interact, think and communicate.

But engagement projects can also become stale or unproductive if the culture of the community is not changed from one that views engagement as strategy rather than as an expectation or standard mode of operation. We have discovered through programs such as the All-America City Award and our learning exchanges with Kettering that some communities have developed a “culture of engagement” which reflects to an unusual degree an engaged citizenry and flexible institutions and managers who find ways of aligning their policies or ways of working with the complementary actions of citizens and community groups.

Civic culture doesn’t spring up overnight, the result of a one-time only engagement process that inspires citizens to be more active or institutions to be more receptive. Nor is it the automatic result of structural innovations aimed at decentralizing local decisions-making with neighborhood councils or priority boards, though these may be valuable in promoting participation. Civic culture arises in communities where multiple efforts to address community problems with engagement have taken root and become part of the locality’s character or way of doing business.

Mike McGrath is Editor of the National Civic Review.

1James Svara and Janet Denhardt, Connected Communities, Alliance for Innovation whitepaper, 2010, p. 5.

2 Horst W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4 (1973), 156.

3 Martin Carcasson, “Tackling Wicked Problems Through Deliberative Engagement,” Colorado Municipalities, October 2013, p. 9.

4 Elinor Ostrom, “Covenanting, Co-Producing, and the Good Society,” PEGS Newsletter, Volume 3, Number 2, p.8.