By Joel Mills

In recent years, our nation has set lofty goals to address our climate crisis while building more equitable communities. For instance, we’ve committed to achieving a net-zero emissions economy by mid-century. The countdown clock is ticking on these big goals, and we need to move quickly to achieve success. Many of our existing local policy frameworks and tools at the community level are undergoing wholesale change as we transform our physical environment. As a result, leaders working on the frontlines of this effort in our communities are facing a civic stress test as conflicts over change become a norm.

Many localities are experiencing tug of wars, civic paralyses, and political stalemates over critically important decisions with incredible consequences for our collective future. We need to reconsider how we approach our public dialogue about community change. Current community dynamics are creating enormous public costs and warped development outcomes. Regional development patterns and path-of-least resistance dynamics fuel both where development occurs and how much of it is realized, often driving gentrification, displacement, and sprawl pressures. These outcomes aren’t climate friendly, nor are they creating more equitable communities. Conflict over community change is an urgent, costly problem. We need a public conversation about how we can improve community dialogue and development outcomes across the country. Consider some of the outcomes we are observing today.

A protest against a new arena district in Alexandria reveals frustration over the lack of details in the public process.

Our Climate Crisis

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), designing more compact urban areas can cut emissions by approximately 25 percent, but between 2010-2020 suburbs and exurbs gained 2 million net domestic migrants, while the urban core lost 2.7 million. That’s the definition of sprawl, with disastrous consequences. The pandemic and work-from-home transition only accelerated this trend, particularly in our most expensive markets. In 2021, research revealed that a jaw-dropping 57 percent of existing structures in the contiguous US are located in climate hazard hotspots, yet we continue to build at disproportionate rates in our most vulnerable locations.

A climate protest in downtown Washington, DC led by university students calls on government to act.

A January, 2024 Berkeley Lab survey of large-scale wind and solar developers underscores the challenge. The survey involved professionals leading community engagement efforts in the solar and wind industry. It found that one-third of wind and solar siting applications during the last five years were canceled, with approximately 50 percent experiencing delays of 6 months or longer. The main causes for canceled projects they identified included restrictive local ordinances and zoning, grid interconnection issues, and community opposition. It was estimated that the average unrecoverable costs realized by these dynamics were $2 million per project for solar and $7.5 million for wind. Furthermore, survey respondents said that opposition is growing and becoming more expensive than it was five years ago, with projections that it will continue to grow in the next 5 years.

A survey of mayors found similar results, with respondents ranking transmission lines (41 percent) and wind turbines (33 percent) among a list of top uses that would generate the most community opposition. Recent surveys of mayors have led to eye-opening conclusions. It appears that we may already be reaching a ceiling of feasible actions under current practices. For instance, the 2022 Menino Survey of Mayors revealed “a big gap between what mayors say they wish they could do, and what they think is realistic,” reporting that mayors did not feel they had the public support to take necessary climate actions. One mayor reported that they “would be hung for going after lawn tools.”

The 2023 survey findings reinforced the key challenges, concluding that “onerous local permitting processes combined with public opposition to new infrastructure projects make it more challenging to build clean energy infrastructure.” Furthermore, a survey of mayors in 2021 discovered an alarming rise in threats to public officials, with 87 percent of local officials surveyed observing an increase in attacks on public officials in recent years and 81 percent reporting having experienced harassment, threats and violence themselves. We need a healthier conversation about community change.

Our Housing Crisis

The dramatic undersupply of housing in the United States, estimated at 4 million units, is a direct result of restrictive land use policies and the public processes that have created them. It is clear that our housing crisis is a significant contributor to systemic inequality in America. Potential first-time buyers are having to compete with global investors and wealthy homeowners. In 2021, almost one in seven homes were purchased by investors, who disproportionately impacted minority neighborhoods. The housing shortage has driven global investors and the wealthy to view housing purchases as sound investments, further constraining housing supply, driving up prices and pushing low-income families away from the American Dream altogether. The median price of a home has risen 37 percent during the past four years to reach an astounding $417,700. Our housing crisis has made it very expensive to live in the US, with inflationary pressures on basic necessities escalating the crisis further. In 2022, 42 million households across the nation were cost burdened, requiring more than one-third of their income for housing.

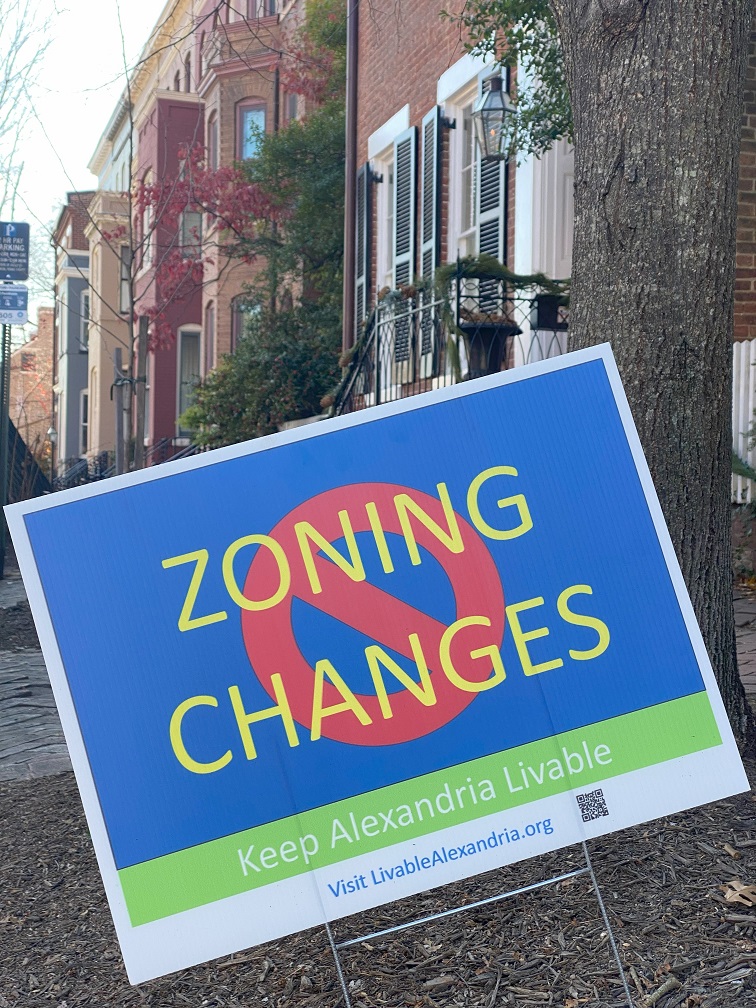

A yard sign in Alexandria, Virginia expresses opposition to the City’s “Zoning for Housing” reforms.

Rents have seen a similar spike, with half of US renters now cost burdened. An affordability migration is underway as people flee housing costs in high-cost markets for more affordable living, thereby driving housing shortages in new communities and creating ripple effects across the country. Many communities face conflict and community opposition that stall major developments and policy changes that would support greater housing supply and affordability. NIMBYs have not only become common shorthand for community opposition, but they’ve also become one of the few issues of bi-partisan concern.

Democratic governor Gavin Newsom famously declared that “NIMBYism is destroying the state” of California, while Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin has expressed frustration that “folks fight tooth and nail to stop almost any development, and we’ve just got to recognize that you can’t complain on one side about not having enough supply and then go lay in the road in order to stop all development.” At the local level, housing conversations are being described in dramatic terms. As one resident of Arlington, Virginia, observed, “It has become this huge community issue – neighbors against neighbors. I mean, it has gotten quite ugly.”

A yard sign in Washington, DC decries a redevelopment proposal to turn public facilities into a mixed use site with more housing.

The Corrosive Impact of Politicization & Conflict

In 2024, the Edelman Trust Barometer finds there is “decline of trust in the institutions responsible for steering us through change and towards a more prosperous future.” The overriding context for most public work today is characterized by pervasive mistrust, and the majority of practitioners have yet to adapt their processes to this reality. Currently, much of what passes for public participation in the field today is producing processes and outcomes that are antithetical to our democratic intent and are having a corrosive impact on our civic infrastructure while yielding few benefits to society.

The lack of technical expertise in deliberative processes, or visible work toward building that capacity, is a major challenge in our profession. Traditional public process designs have overly relied on limited representation and simple input and feedback mechanisms that are no longer sufficient to meet public expectations or create awareness and understanding of our choices. The resulting conflicts and mistrust are having profound impacts. There is a growing narrative of civic decline. In many cases, poorly designed public processes fail to meet public expectations for meaningful participation, causing civic frustration and conflict and a resulting loss of trust. A smaller, less-representative public leads to more dominance of the conversation by extreme voices and narrow interests, which causes a decline of civil dialogue and increasing politicization of the issues. This can lead to personalization of the conflict and vilification of public leaders or representatives of opposing positions.

As it continues to build, a state of distrust and endemic conflict can begin to take hold, often leading to public sector retreat on both issues and public participation itself. In some cases, government begins to actively fear the public, leading to the cannibalization and dismantling of democratic infrastructure and the circumscribing of public opportunities for involvement as local leaders try to stem conflict and regain a sense of control. For instance, some cities have dismantled neighborhood council systems in recent years as they became politicized, less representative, and served as a breeding ground for more extreme neighborhood activism rather than a mechanism for public voice and collaboration.

In addition, multiple jurisdictions in recent years have been accused of skirting open meeting laws or holding secretive backdoor deliberations about important developments or circumscribing public opportunities for participation in an effort to short circuit potential opposition and community backlash. This results in less trust or appetite for participatory processes, which ironically feeds the further development of the cycle. In extreme cases, civic anger can reach a tipping point where community and social capital suffer severe and lasting damage and civic infrastructure requires wholesale change in order to avoid the loss of faith in democratic institutions and the loss of participatory traditions. It has never been more apparent that our civic health and trust in institutions is inextricably linked to our capacity to solve our greatest challenges.

Reason for Hope

A yard sign in Washington, DC expresses support for new development and housing to address the regional housing crisis.

There are hopeful signs that public opinion is shifting toward support of dramatic action. A majority of Americans (55 percent) support their local government setting goals to create ”15-minute cities” with compact urban form. A third of Americans are now “alarmed” by climate change, and two-thirds of citizens would like to see more government action to address it. A survey last year found that 74 percent of Americans are concerned about the lack of affordable housing in their community and only 26 percent feel their voice is being heard on the issue. Less than 40 percent of respondents feel that local (37 percent) and state (35 percent) policymakers are taking the issue seriously. We simply need to use mechanisms at the local level to facilitate better dialogue about community change. Current challenges compel us to re-examine practice and consider important new innovations in the field that are combining civic deliberation and public decision-making, updating legal frameworks and addressing governance gaps to produce better outcomes. To improve our outcomes, we will need a new civics. This may be the greatest opportunity we face as civic leaders to engage our citizens in the critical public choices we face. There is a groundswell of popular support to have a new conversation about our communities. It is an opportunity that we should seize.

Joel Mills is Senior Director of Communities by Design at The Architects Foundation