By Lindsay M. Miller

In his book, The New Geography of Jobs, economist Enrico Moretti describes the change Seattle has seen in the past few decades. In the 1970s, Seattle was riddled with job loss, economic decay, and struggle. Yet, over the past thirty years, economic development fueled by public and private investment has turned the city around:

Seattle is not the same city that it was thirty years ago. Dilapidated warehouses have been rehabilitated to host scores of small startups, and smart-looking new office buildings have been erected for larger companies. The once crumbling pier and rusting docks now house Internet and software companies…A formerly seedy residential and commercial district on the northern edge of downtown has become the cool city’s new zip code, with well-designed offices and condominiums appearing every year.1

Seattle is one of the fastest growing cities in the nation and has been able to harness the influx of capital to promote future growth. As Moretti describes, places that were once derelict and impoverished have been remade into “cool” and “hip” neighborhoods that now attract newcomers due to improved amenities, a lively cultural scene, and upscale housing.

Urban Growth and Gentrification

While Seattle is not one of the global economy’s “superstar cities” like New York, London, Los Angeles, or Tokyo, it is a quickly growing city that is clearly winning in the contemporary creative economy. Cities like Seattle, Denver, New York, and Chicago have been able to recreate themselves to succeed in an economy that relies on urbanization, density, and “clustering” of talent in diverse metropolitan areas to thrive.2

Though these “success stories” should not blind us to the struggle still present in many of the urban centers across the country, cities like Seattle are important to examine for the insight they might give us on matters related to growth and social equality. Specifically, they can tell us what to look out for when a city’s economic development strategies go right.

Successful economic development and growth are worthy goals; they provide residents with stable incomes, produce a strong tax base to perform services, and allow for quality infrastructure and public amenities. Yet, unplanned growth, or planning without a strong equity lens, can produce a range of other problems, including affordable housing crises, increased homelessness, inflated cost of living, or gentrification-induced displacement of long-term residents.

Seattle’s Equitable Development Framework

Seattle is an exceptional example of a city working to manage its growth with an equitable framework so that economic vitality can be enjoyed by all its residents. Utilizing proactive civic engagement, the city has been able to encourage growth in economically struggling neighborhoods that includes the input and guidance of residents in every stage of the process. Seattle has demonstrated that when residents are included in planning and development, particularly those that have been historically excluded from planning and other local government processes, all residents can be poised to both contribute to and reap the benefits of growth.

The Beginning

Seattle’s inclusive planning process began in the 1990s when the city worked with residents in 38 neighborhoods to develop 20-year visions for how each neighborhood would grow. As part of the Seattle Comprehensive Plan initiative, the city sought to “preserve the best quality of Seattle’s distinct neighborhoods while responding positively and creatively to the pressure of change and growth.” The goal of the neighborhood plans was to ensure a “creative response” to growth that was “informed by both City expertise and local knowledge and priority-setting.”3 A coalition of residents and city leaders produced 38 independent neighborhood plans for each neighborhood with the vision of producing long-term, equitable, and sustainable development that benefited all of Seattle’s residents.4

In the 2000s, about a decade after the plans were completed, residents and city leaders became concerned with the pace of Seattle’s growth. Although the plans were intended to guide the city’s efforts for 20 years, city leaders and residents began to feel that such dramatic change necessitated an update to the neighborhood plans. Thus, in 2008, the Mayor and City Council decided it was time to revisit the plans and create official Neighborhood Plan Updates.

Neighborhood Plan Updates

The goals of the plan updates were the following:

- Confirm the neighborhood Vision,

- Refine the plan Goals and Policies to take into account changed conditions, and

- Update work plans to ensure that each community’s vision and goals were implemented with thoughtful strategies and action plans.5

The Mayor chose three plans to be updated in 2009: The Othello Neighborhood Plan, the Rainier Beach Neighborhood Plan, and the North Beacon Hill Neighborhood Plan. These neighborhoods were chosen, in part, because light rail service had been added to the neighborhoods, spurring development and private investment. Residents wanted to ensure that the development would benefit the residents of the community, create jobs, and preserve the neighborhood’s distinct character. They also wanted to ensure that development would not increase rent or housing costs so much that long-term residents would be forced to move out. In other words, the plan updates were, to some extent, a response to gentrification.

Community Engagement

Southeast Seattle is home to some of the most diverse zip codes in the country, with over forty distinct ethnic groups and demographics that include 38 percent Asian, 28 percent black, 19 percent white, 8 percent Hispanic, and 1 percent Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.6

Extensive community engagement was utilized from day one of the plan update process with the explicit purpose of gathering input from historically under-represented communities. The city wanted to ensure that plans for each neighborhood were not just created with input from residents, but that residents were involved in the entire process of the creation and implementation of the plans.

The city used some traditional tools to engage community members, such as hands-on workshops, smaller-scale interactive meetings with community-based organizations, and online updates and questionnaires. They also utilized bicultural and/or bilingual Planning Outreach Liaisons (POLs) to connect with underrepresented communities. In the Othello neighborhood alone, the POLs hosted 43 community workshops where historically underrepresented Othello community members participated. They also created culturally-appropriate opportunities for dialogue by meeting residents where they already worked, congregated, and spent free time. The POLs included liaisons for the Somali speaking community, the Vietnamese speaking community, the African American community, the Spanish speaking community, the Chinese speaking community, and others.

The first phase of the update process included workshops where residents described what they felt made their neighborhood unique, what they valued in their community, and how they saw it changing over the following years. They described how they went about their daily lives—living, working, and playing in the neighborhood. A Healthy Living Assessment was also conducted during the first phase to focus attention on how planning for the neighborhood could improve health. These discussions helped identify some of the residents’ needs and desires for a healthy, vital community. The POLs extended this conversation into their communities throughout the year.

The initial conversations were followed by town halls where residents participated in interactive exercises to “identify gaps and opportunities” for improving the neighborhood.7 The community’s goals and desired improvements grew from this second phase of meetings.8

The final stage of the plan update process was to utilize open houses to review goals and recommendations that grew from the engagement efforts throughout the year. City leaders, POLs, and leaders of community organizations summarized the proposed plan recommendations to residents and encouraged participation beyond the planning process and into the implementation phase.

Insights from Two Neighborhood Plan Updates: Othello Neighborhood and Rainier Beach

Rainier Beach

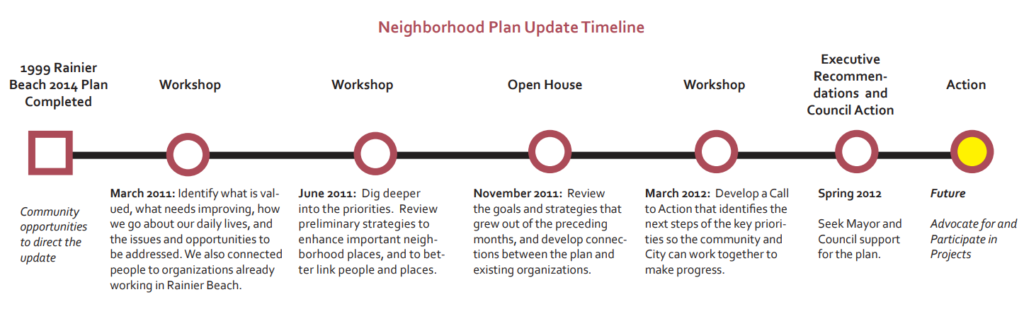

Rainier Beach’s neighborhood plan updating process utilized the following timeline:9

The Rainier Beach Neighborhood Plan Update identified the following priorities through the Healthy Living Assessment: Strong Community, Healthy People and Families, and Great Places. The plan suggested creating a shared multicultural community center to strengthen the existing culturally and ethnically diverse communities in the area by providing a space for services and cross-cultural events. A Multicultural Community Center is now being developed as part of the Othello Square project in the adjacent Othello neighborhood.

Othello Neighborhood

The Othello Neighborhood Plan Update included goals in three areas: to maintain and encourage the neighborhood’s diversity; to promote community development and a strong local economy; and to improve safety and access to educational, social, and employment opportunities.

These goals, identified by the community members themselves, represent a clear commitment to equitable development and what the Puget Sound Sage—a Seattle-based organization committed to justice for low-income communities of color—calls “prospering in place.” Prospering in place is identified as the “opposite of gentrification-fueled displacement, where “low-income people and families can afford to stay where they are, access the region’s economic opportunities and deepen cultural roots in their existing communities.”10

Outcomes

The City of Seattle’s work to engage communities in equitable development is innovative not just because of their extensive and transformative civic engagement efforts, but because these efforts have brought tangible projects into fruition. The projects included in the neighborhood updates are being implemented by two multi-sector organizations: the Rainier Beach Action Coalition (RBAC) and On Board Othello.

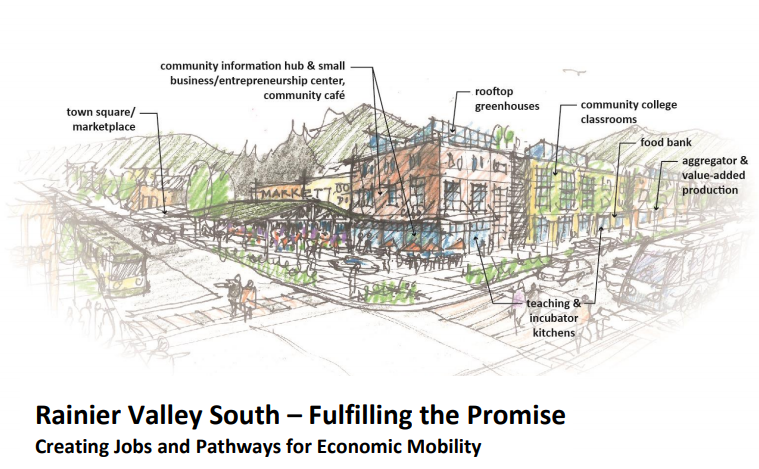

Rainier Valley South—Fulfilling the Promise

“Rainier Valley South—Fulfilling the Promise” is a coordinated action plan developed by the City of Seattle Department of Planning and Development to implement the goals in the Rainier Beach Neighborhood Plan Update.11 The action plan includes implementation plans for the following projects that are now underway:

- Food Innovation District: an area around the Rainier Beach light rail station envisioned to be a node for attracting food businesses to the neighborhood and to create pathways to livable wage employment, education, and business opportunities. It will serve as a network of uses and activities related to food business that may include a food hub, co-packing, commercial kitchens, food science, and research.

- Rainier Beach: A Beautiful, Safe Place for Youth: a community-led initiative that aims to reduce violence that affects youth in the Rainier Beach neighborhood. It works to identify and address the place-based causes of youth victimization and crime by engaging the Rainier Beach community, Seattle Police, community-based organizations, businesses, and schools. It also works to implement non-arrest interventions by utilizing research from the George Mason University’s (GMU) Center for Evidence-Based Crime Prevention Policy.

- Beer Sheva Park improvements: The planning and design process for improvements to Beer Sheva Park in the Rainier Beach neighborhood was informed by extensive community involvement. The planning and design stage has been completed and improvements are now underway.

Othello Neighborhood

- Othello Square Development Project: an equitable development project planned for the largest plot of undeveloped land in the neighborhood. It will offer over 200 units of cooperatively owned and mixed-income apartments, affordable retail space, an early learning center, a public high school, a business incubator, a health clinic, and a multicultural center. It will support more than 350 living-wage jobs, preserve small businesses, and nurture entrepreneurship among community members of color.12

- Multicultural Community Center: Part of the Othello Square project, the Multicultural Community Center will serve as a cultural home and vital service center for over 10,000 immigrants, refugees, people of color, and other community members in Rainier Valley.

Community Cornerstones Program

In 2011, the City of Seattle was awarded a $3 million Community Challenge Grant by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to work on priorities identified in the neighborhood plan updates. Community Cornerstones is the resulting grant-funded program that brought together multiple City departments, financial institutions, and other partners to implement a new model for equitable development in the Southeast Seattle light rail station areas. The three community development strategies that the program focuses on are the following: an Equitable Transit-Oriented Development (ETOD) Loan Program, a commercial stability strategy to stabilize and grow local businesses, and a plan to build the Othello Square Multicultural Community Center.13

Conclusion: Equitable Development as a Tool to Address Urban Poverty

Gentrification is a hot topic in city planning, public administration, race and ethnic studies, and social justice more broadly. It is, in part, a result of decades of discrimination, inequitable urban policy, and income disparities that drive an ever-deepening wedge between whites and communities of color. Rightfully so, gentrification spurs strong reactions, particularly from those in fast-growing cities that are most at risk of losing, or not benefiting from, rapid urban change.

Although gentrification seems to dominate the media coverage of equity issues in urban centers, it is actually a relatively infrequent occurrence. In a study of high-poverty neighborhoods in 51 metropolitan areas, only five percent of neighborhoods gentrified. Much more common is the spread and proliferation of chronic, high-poverty neighborhoods in which 75 percent of residents are people of color.14 Thus, Seattle’s challenges related to rapid growth are significant, yet relatively uncommon when compared to challenges facing the majority of U.S. cities.

Despite the fact that gentrification is relatively rare, it catches our attention. This is because gentrification is a result of what so many urban centers—and many low-income communities—want: strong local economies, more and better jobs, and public investment to improve quality of life. Gentrification occurs when neighborhoods improve, even on relatively objective measures like access to public transportation, quality of public space, and walkability.

Because of this, urban poverty often seems insurmountable; poor neighborhoods need investment, but investment leads to gentrification. Much like the mythical monster Hydra—a serpentine creature with many heads—for every head we cut off, two more grow in its place.

Yet urban poverty need not be the beast that will never die. We must talk about gentrification not to prevent urban growth, but to ensure that growth is carefully planned with particular attention to social and racial equity. Equitable development—as exemplified by the City of Seattle—can be one of the tools we use to end urban poverty for good.

Lindsay M. Miller is a Robert H. Rawson, Jr. Fellow at the National Civic League. She holds a Master of Social Sciences in Social Justice and is completing her Master of Public Administration at the University of Colorado Denver. She would like to thank Robert Scully, Senior Planner of Equitable Development for the City of Seattle, for his thoughtful contributions and feedback on this article.

1 Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: Mariner Books, 2012), 71.

2 Richard Florida, The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can Do About It (New York: Basic Books, 2017).

3 “Othello Neighborhood Plan Update,” City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development, Jan. 2010, available at https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/OPCD/Vault/Othello/OthelloNeighborhoodPlanUpdate.pdf.

4 “Neighborhood Planning,” City of Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, available at https://www.seattle.gov/neighborhoods/programs-and-services/neighborhood-planning.

5 “Othello Neighborhood Plan Update.”

6 “Rainier Valley South—Fulfilling the Promise: Creating Jobs and Pathways for Economic Mobility,” City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development, Nov. 2013, available at https://clerk.seattle.gov/public/meetingrecords/2014/cbriefing20140331_3c.pdf.

7 “Othello Neighborhood Plan Update.”

8 Ibid.

9 “Rainier Beach Neighborhood Plan Update,” City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development, March 2012, available at https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/OPCD/OngoingInitiatives/RainierBeach/RainierBeachNeighborhoodPlanUpdate.pdf.

10 Ubax Gardheere and Lauren Craig, “Community-Supported Equitable Development in Southeast Seattle,” Puget Sound Sage, Feb. 2015, available at https://pugetsoundsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CommunitySupportedEquitableDevelopment.pdf.

11 “Rainier Valley South—Fulfilling the Promise.”

12 “Othello Square,” https://othellosquare.org/.

13 “Community Cornerstones,” City of Seattle Office of Housing, Jan. 2013, available at https://clerk.seattle.gov/~public/meetingrecords/2013/cerrr20130416_4a.pdf.

14 Joe Cortright and Dillon Mahmoudi, Lost in Place: Why the Persistence and Spread of Concentrated Poverty—Not Gentrification—Is Our Biggest Urban Challenge (Portland: City Observatory, 2014), available at https://cityobservatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/LostinPlace_12.4.pdf.