By Steve Redburn, Barbara Dyer, and Richard Callahan

Though a societal challenge, the experience of homelessness is local, varied, and complex. Solutions must be developed community by community, tailored to individual circumstances. But essential financial resources and technical expertise exist within all levels of government, and across sectors. Addressing homelessness requires civic engagement that recognizes no one level of government or one sector alone can be effective. It calls for an intergovernmental systems and cross sectoral approach that connects funding and services across traditional public, nonprofit, and private boundaries, with leaders working collaboratively over time.

Though a societal challenge, the experience of homelessness is local, varied, and complex. Solutions must be developed community by community, tailored to individual circumstances. But essential financial resources and technical expertise exist within all levels of government, and across sectors. Addressing homelessness requires civic engagement that recognizes no one level of government or one sector alone can be effective. It calls for an intergovernmental systems and cross sectoral approach that connects funding and services across traditional public, nonprofit, and private boundaries, with leaders working collaboratively over time.

What’s Working?

Recently, the National Academy of Public Administration, (NAPA) Working Group of Academy Fellows, of which we were a part, released a report on how communities were grappling with the challenge of reducing homelessness.1 We looked for places that had some success, with the aim of understanding the intergovernmental and civic engagement dimensions of their progress. We asked: How do local, county, state, and federal players, programs, and systems support reducing the number of individuals experiencing homelessness?

We looked closely at three places:

- Houston, Texas, where since 2010, a local nonprofit, working closely with the mayor and other leaders, orchestrated the participation of more than 100 partners to deliver an integrated effort that reduced homelessness by more than 60 percent in a decade.

- Santa Clara County, California, where a strong partnership of local government and nonprofit agencies adopted a goal of housing 26,000 people between 2015 and 2025, and is making headway even as affordable housing options shrink in this wealthy, vibrant region.

- North Central Massachusetts, where local leaders—including a community foundation, a state representative, and city housing officials—partnered with the state’s housing agency to form an alliance focused on reducing homelessness. This collaboration aimed to provide immediate shelter while also developing new supportive housing and other strategies to help people secure long-term housing.

In each case, three features of civic engagement emerged. One, civic and political leaders served as catalysts for bringing communities together. Two, collaboration engaged the public, private and nonprofit sectors. Three, networks developed for integrating service delivery.

Some Recent History

Starting in the 1980s, the federal government mounted a series of bipartisan initiatives to reduce homelessness. Many efforts originated in the Stuart B. McKinney (McKinney-Vento) Act of 1987, signed during the Reagan Administration. Efforts continued in succeeding administrations, with a focus on chronic homelessness beginning in the early 2000s and later a specific focus on helping homeless military veterans.

In the 2000s, with advocacy from non-governmental groups such as the National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEM), policy goals shifted from providing emergency shelter and succor to reducing homelessness by helping people find places to live. This new housing first focus produced localized results, particularly among military veterans. Thanks in part to extra federal resources and attention, the number of homeless veterans is now less than one-half of the number in 2010. But, more recently, while progress continues in some places, homelessness has again surged.

Homelessness as an Intergovernmental Challenge

Localities bear the burden imposed by high numbers of people living outside, in cars, and other makeshift or emergency shelters. They are chiefly responsible for directly administering and helping pay for initiatives to reduce homelessness, in most cases receiving support from federal and state governments.

The intergovernmental system with federal, state, counties, districts, and municipalities does not make it easy to tackle such boundary-crossing problems. Each federal program has a distinct set of application criteria, reporting requirements, auditing processes, eligibility and use rules, and often burdensome administrative requirements. This structure is at once bewildering and drives local and state officials to focus more on the vertical dimension of compliance and reporting upward and less on generating ground-level results. Incentives and financial support are weak for building effective horizontal networks for joint action among essential actors across the intergovernmental system.

If even the most knowledgeable local government and civic actors find the system hard to comprehend, individuals experiencing homelessness find the task of accessing services daunting. Agencies at all government levels must help people navigate systems to obtain services appropriate to their needs. Given the challenges the intergovernmental structure presents, it is remarkable that localities have managed to construct coordinated responses. In those that we examined, civic leaders and service providers came together voluntarily and committed to common objectives, then formed influential and effective networks to deliver coordinated outreach and services to those facing homelessness.

In an attempt to address coordination and other issues, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development supported the Continuum of Care (CoC) program. Nationally, over 400 CoCs are charged with promoting a coordinated local response by nonprofit and government providers of services to homelessness, including promoting their access to mainstream federal assistance programs and establishing a Homeless Information Management System (HIMS) to support integrated planning and delivery. Although CoCs help with coordination, many lack the capacity and authority to overcome jurisdictional and functional fragmentation and conflict. Recent studies of CoCs describe their challenges in coping with surges of first-time homeless persons seeking housing and with the administrative burdens that accompany grant funding. In densely populated areas, a mobile population of those experiencing homelessness may cross multiple CoC service areas. Despite their limitations, CoCs can be important catalysts in building a more integrated and results-driven approach in many places.

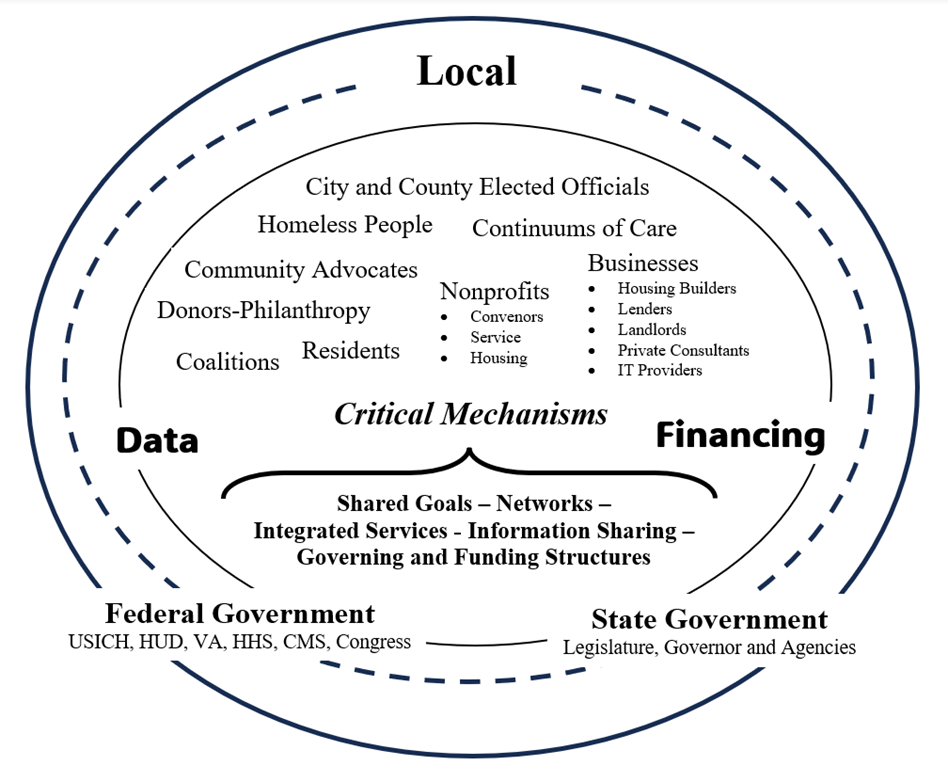

As illustrated by Figure 1, an effective response to homelessness addresses the intergovernmental system’s horizontal and vertical dimensions. Horizontally, initiatives require an integrated approach by a coalition of local actors in the public, nonprofit, and private sectors committed to shared goals and strategies, with the capacity to coordinate actions across often siloed and geographically divided programs. Vertically, effective responses engage cities, counties, districts, and regions with state and federal governments, including elected officials, in coordination with managers and staff.

Figure 1. A Framework for Homelessness Responses in the Intergovernmental Context

Source: National Academy of Public Administration Working Group on Homelessness (2024)

Within this complex context of intergovernmental and cross-sectoral efforts, the NAPA study group identified five common features across the three case studies that contributed to effective policy implementation and program development.

Five Common Features

The local choice of strategies addressed and reflected local circumstances: current political realities, policy changes, administrative arrangements, and resource limits. Despite the wide range of differences, we observed that places achieving success had incorporated the following features.

First, a catalytic group of leaders engaged in a rigorous process to define, commit to, and communicate the challenge of homelessness. This process facilitated the emergence of agreement on shared goals, objectives, and coordinated strategies.

Each case began with a process of civic engagement involving core groups of people with knowledge, authority, and reach, in various combinations of elected, nonprofit, and private leaders; public administrators; and other experts. In Central Massachusetts, for example, the Community Foundation of North Central Massachusetts was catalytic in bringing state legislative leaders, the state’s executive housing agency, the Central Massachusetts Housing Alliance, the faith-based community, the CoC, and others together to generate solutions.

Across the sites we observed, local leaders forged closer connections with all stakeholders—ranging from government officials to businesses, nonprofit organizations, and the philanthropic community. They work to communicate about the problem, their goals, and their strategy with the public. Effective communication by leaders can also address localized concerns about the siting of housing for homeless persons in a particular neighborhood.

In each case, leaders formed an informal alliance held together by a shared commitment to reducing homelessness, a joint plan of action, and a practical strategy with assigned and orchestrated roles for the various players. In Santa Clara, for example, a broad coalition of government, nonprofit, and other partners has now raised over $2 billion in local public and private funding and produced two consecutive five-year “Community Plans to End Homelessness.”

A locality’s initial choice of strategy is a critical step. Success developed from a strategy in each place that effectively responded to the specific context of local circumstances, including current political realities and administrative arrangements, funding, and policy choices that consider those realities. In each place we observed, the strategy continued to evolve, responding to changing leadership and ever-changing challenges.

Second, local leaders built broader networks of organizations to work together toward shared goals and develop coordinated and synchronized implementation.

The diversity of events and circumstances that contribute to a person becoming homeless—an eviction, job loss, an illness, an addiction, a pandemic, a natural disaster—results in a diversity of needs that must be addressed before they can move from the street into a home and remain there. Building a system that can deliver timely and effective help requires building a network. These responses span functional and geographic jurisdictions of many actors and agencies that offer one or more services, such as housing assistance, employment assistance, and health and mental health care. Responses often cross political and sectoral boundaries–no one level of government, agency, or sector can solve homelessness alone. We found that each place built a network to coordinate and align the complementary efforts of local actors.

We observed that forming effective local networks involved:

- Initiative by a neutral, trusted party with resources, such as a community foundation, convening the civic, political, and business leadership to prime the pump and coordinate among them

- Participation at the start by those with relevant expertise and authority

- Cultivating trust among participants by sharing information, joint problem-solving, and demonstrating commitment, learning from the community and developing public trust

- Adopting specific tools that facilitate practical actions to help develop housing and services options, including project financing for low-income housing, streamlined permitting, and greater efforts to increase landlord acceptance of housing vouchers.

Participants include appointed and elected officials as well as decision makers on matters as wide-ranging as land use, housing development, criminal justice, welfare, and health services. Lacking formal authority over their local partners, the federally funded CoCs have helped by building shared commitment and specific working agreements among agency partners. These networks also gathered and used data to improve processes, track results, and inform decision making.

In Houston, a broad coalition of public and private partners has designated The Coalition for the Homeless of Houston/Harris County as the lead agency since 2011 for its network, which it calls “The Way Home.”

In all three localities, the network determined what problem they would solve, set clear, actionable goals with joint strategies, and sought to learn from their efforts. They balanced the urgency to make immediate progress with the desire to achieve longer-lasting results. As networks formed out of necessity to address a pressing problem, they resembled emergency responders that come together after a disaster rather than long-standing public/private authorities designed to endure stable staffing and financing. The advantage of dynamic networks is that they are flexible, nimble, and creative. The disadvantage is that they must eventually confront questions regarding their future management and sustainable financing.

Third, the network delivered timely integrated services appropriate to the needs of each person who is homeless or facing homelessness.

Effective delivery requires aligning local efforts with federal and state programs so homeless individuals and families receive tailored services and support unique to the circumstances of each. A comprehensive and tightly knit network is required to deliver timely integrated packages of housing assistance and other services. The national nonprofit Community Solutions works with over 100 localities to help organize homeless response systems that include dedicated providers such as CoCs but are broader–incorporating agencies from intersecting sectors, for example health and mental health, in an integrated effort to both prevent and reduce homelessness. They help localities overcome structural barriers to providing orchestrated services to the homeless population.

Because there is no authority capable of assigning roles and directing the services required in each place and for each homeless person, government leaders and service agencies must broker agreements among independent providers that define the delivery model. It’s a challenge to provide integrated services through a distributed network without a designated authority responsible for orchestrating delivery, but the places we looked at developed agreements among government and non-government actors to collaborate in ways that support integrated services appropriate to each person’s needs.

In a decentralized and fragmented system, getting the right services to a homeless person requires someone who specializes in helping individuals access the aid they need. Whoever plays this broker or navigator role must have the skills and tools to reach out to and understand the needs of homeless persons; they must form professional relationships to connect them, when ready, with sources of housing assistance and other services needed for them to move from the street. The role of the navigator/services broker/integrator needs to be clearly defined. It may be played by various local agency staff and funded from multiple sources. If the role is not adequately filled, local delivery efforts may falter.

Housing assistance is central to any strategy to head off homelessness or reduce the number living on the streets or in emergency shelters. Local Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) are critical actors; they administer public housing and portable housing vouchers that help people rent private apartments. Integrating PHAs’ work with other service elements of integrated delivery to reduce homelessness illustrates the broader challenge of designing an integrated services strategy.

Many local service systems cannot provide people without homes sufficient access to housing assistance linked to supportive services. Administrative and other barriers reduce access by homeless persons with disabilities to income support for which they are eligible, including Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). This income would help pay for housing and may provide eligibility for Medicaid-funded aid in securing housing and other support. The ability to close the access gap also depends on the priority local PHAs give to the homeless population for longer-term housing assistance.

The emphasis on prevention emerged and grew over time in both the Houston and Santa Clara cases. Effective delivery of preventive services to those most at risk depends first on understanding the social processes that may lead to the street—including youth aging out of foster care, those returning to their communities after incarceration, those fleeing abusive relationships, and newly arrived migrants without local contacts—then having a method to identify individuals within these larger flows who are most at-risk and provide those people with appropriate interventions. Our assessment is that designing cost-effective preventive efforts stretches the capabilities of many localities.

Fourth, they shared data, analyzed to inform planning, prioritization, and tracking of assistance to homeless persons.

Developing systems to generate person-centered data helps ensure integrated, timely delivery of services appropriate to each person’s situation. Data collection can support evidence-driven decisions with person-centered, comprehensive, and real-time data facilitates local actors making needed adjustments that address gaps in their delivery system. Those working to prevent and reduce homelessness need to access and analyze high-quality data to inform their actions. Data about housing—such as supply and cost trends of occupied, available, and planned housing—suggest where to focus future action.

Some jurisdictions have built the capacity to link and analyze individual-level data, which gives them insight into the dynamics of homelessness, helping them better target and coordinate service delivery. It also gives them a more powerful tool to measure outcomes and evaluate impacts than can be had with only aggregated and not legally protected data. As one might expect of a place known as the Silicon Valley, Santa Clara has used data to gain a deeper understanding of the root causes of homelessness there.

Increased technical support for those places can facilitate modern data standards for individual and real-time data, more user-friendly technology, and deeper investments in the human capacity to manage data would serve the interest of more significant equity across places and increase their ability to use local data to learn and to target outreach and services.

Using data to track individuals as they have contact with multiple agencies and to support integrated service delivery raises another layer of issues regarding data security and personal privacy. These issues might be overcome by offering localities models for data sharing and use that have been shown to address them successfully.

Fifth, local leaders work to create or strengthen governance and financing structures that can sustain and improve local efforts over time.

In the places we examined, initial successes were driven by talented, committed leaders who brought together local and regional actors across jurisdictional divides to forge informal, effective working relationships around a common objective. Initial informal voluntary networks eventually shifted to formalized structures to sustain momentum and withstand inevitable changes in leadership and funding over time.

As they formalized their working relationships, localities continue to rely on funding to support their long-term strategies and operations. This need for sustainable funding calls for an intergovernmental approach. Initial efforts to sustain funding for the future have taken different forms. Just as developing plans and strategies and then implementing them must engage the whole community, so too must the responsibility for funding be shared. As major funders of local services, states and the federal government can play important roles by ensuring the financial sustainability of local efforts.

While essential, formalizing and sustaining these coalitions is tough to do. The places we examined are each struggling with this challenge. Beyond the three case studies, the largest numbers of individuals experiencing homelessness are in large metropolitan areas. For example, in Los Angeles County, with over 10 percent of the US homeless population, a new effort is underway to form a consolidated organizational structure. Voters there have just approved a .25 cent sales tax increase dedicated to homelessness and low-income housing. Many other places will be watching this effort closely and will draw lessons from it.

The five features described above, although presented here as a sequence, are nested layers of continuous activity. Each feature interacts with the others in specific mutually reinforcing ways. For instance, as the players gained experience with the delivery model, they identified gaps to fill by bringing new members to the network. Data drawn from experience became the basis for a common understanding of the problem, consensus around goals, and continuous improvement in the execution of strategies.

Conclusion

Across the United States, the pressure is mounting to develop effective strategies to reduce homelessness. Local, state, and federal governments along with nonprofit and private leaders continue to explore what they can do together, to learn from each other’s experiences and overcome barriers to practical intergovernmental approaches to reducing homelessness. We came together as a NAPA Working Group to observe some successes, spark conversation, raise important questions, and contribute to practice. But it is catalytic civic and public sector leaders who are working tirelessly to build the coalitions and to create the strategies and implementation networks that will ensure that the experience of homelessness in America becomes rare and fleeting.

Steve Redburn worked for 20 years in the Office of Management and Budget, where he was senior career executive leading staff responsible for advising on policy, management, and budget for housing and urban development. He is Professorial Lecturer in the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration, George Washington University, teaching graduate courses on the federal government’s budget process and institutions.

Barbara Dyer is Senior Fellow and Research Affiliate at MIT Sloan’s Institute for Work and Employment Research, where she had been Senior Lecturer and Executive Director of the Good Companies, Good Jobs Initiative. Before MIT, she served 18 years as president & CEO of the Hitachi Foundation following leadership roles in federal and state policy research and development.

Rich Callahan is a Professor at the University of San Francisco. He is also a Founder and Partner in TAP International, a consulting firm for training, analytics and program evaluation. He is an elected Fellow and on the Board of Directors of the National Academy of Public Administration. His research, teaching, and consulting focus on strategies and leadership behaviors that are effective in complex and dynamic environments in the public and nonprofit sectors.

Sources

1 Working Group of the National Academy of Public Administration. 2024. Reducing Homelessness in the United States: An Intergovernmental Challenge. National Academy of Public Administration. Accessed November 18, 2024. https://napawash.org/standing-panel-blog/reducing-homelessness-in-the-united-states-an-intergovernmental-challenge.