By Doug Linkhart

One of the biggest success stories of the nation’s response to COVID 19 was Alameda County, California, and its largest city, Oakland. While the country struggled to get people vaccinated and protected from infection, Alameda County and Oakland were among the best performers in the country when it comes to death rates and vaccinations, despite having a large proportion of more-vulnerable residents, including many people living in poverty.

Around the world, community trust and support were critical to minimizing the damage from COVID 19, since cooperation from the public was needed regarding vaccinations, mask-wearing, testing and isolation. Research has shown that, in countries with greater trust and civic engagement, deaths from COVID 19 were lower. And establishing that trust through civic engagement was key to the pandemic efforts in Alameda County.

By involving community leaders in decision-making and reaching out through nonprofit organizations, churches and other trusted sources of information, the county and city were able to build trusting relationships with populations that were more vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic because of structural disparities like poverty, racism and increased exposure to risks.

“The main factors in higher mortality rates revolve around lack of access to the resources and supports one needs to be healthy, like a living wage job, high-quality healthcare in your own language, provided by people who are culturally relatable whom you trust, and safe, clean, and affordable housing,” said Alameda Public Health Director, Kimi Watkins-Tartt.

And while these factors have created health disparities nationally for many people of color and people in poverty, Alameda County and the City of Oakland empowered grass roots leaders and community networks to minimize the impact of the pandemic on these communities. “Diversity is one of our assets,” said Watkins-Tartt. “We used a coalition model, using community-based organizations so that people felt more comfortable, felt good coming, and felt like ‘I’m welcome here,’” said Watkins-Tartt.

Dr. Noha Aboelata, Founding Director of the Roots Community Health Center, a clinic serving Oakland and other Bay-Area cities, agrees with the importance of community engagement, attributing the county’s success to “strong community organizations coming together early on. In our network different groups leveraged each other. Our saying was ‘Never close any door.’ We kind of leaned on each other. Everyone knew they had to pull together.”

Successful Outcomes

During the first two years of the pandemic, 2020 and 2021, Oakland was 2nd and 3rd, respectively, among the nation’s largest cities for low death rates. Alameda County, which encompasses four times the population of Oakland, with over 1.6 million people, placed in the top two percent of counties nationwide, #60 of 3,002, during the period from 2020-2022, with only 28.1 deaths per 100,000 population.

Both Oakland and Alameda County have also had high vaccination rates as a result of their communitywide outreach. In 2021, Oakland had the fourth highest vaccination rate among large cities nationally, at 85.5 percent. And, as of the end of 2022, 84 percent of Alameda County residents had received at least one vaccination, compared to 69 percent nationwide.

These successes come despite Oakland and Alameda County having a high proportion of people who were more vulnerable to COVID’s effects because of long-standing health disparities caused by social, economic and environmental factors.

As of 2022, Oakland had a population of 430,553, with an ethnic breakdown reflecting 29.0 percent white non-Latino, 15.9 percent Asian-American, 26.6 percent Latino, and 21.8 percent Black, and 6.7 percent other, with a poverty rate of 13.2 percent, compared to a national poverty rate of 11.5 percent. Alameda County, as a whole, has double Oakland’s Asian-American population, but still with only 29 percent of its residents being non-Latino white, and a poverty rate that is slightly better than the national average, at 10.1 percent.

A Focus on Equity

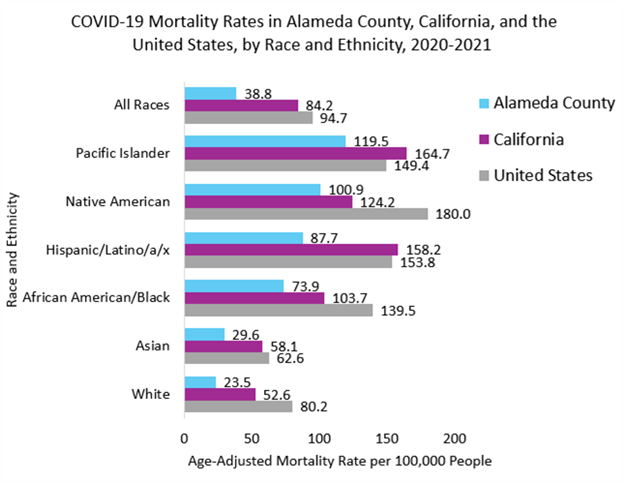

Oakland and Alameda County, like the nation as a whole, have suffered from long-standing health disparities that have aggravated the pandemic’s effect, with Black, Latino, Native American and Pacific Islander populations experiencing higher death rates from COVID 19 than whites and Asian-Americans, as shown in the chart below for Alameda County.

Recognizing these disparities and the likely disproportionate effect on underserved populations, the State of California adopted an equity approach, allocating vaccinations to the least-resourced areas, and not allowing counties to reopen until they showed progress in those areas. “Measuring our equity data pushed the counties to focus resources where they were needed the most, and where they’d have the most impact,” said California State Epidemiologist and former health officer for Alameda County, Dr. Erica Pan.

Both Dr. Pan and the county acknowledge that, despite the area’s success, there are still disparities in health outcomes for different populations, but, said Kimi Watkins-Tartt, “the gaps would’ve been much greater had we not taken this approach.” Indeed, the death rates for each of the major ethnic groups in Alameda County have been well-below the national average for each group, with the death rates since the beginning for Blacks, Latinos and Asian-Americans in the county being roughly half their respective national averages.

“The extra measures we took in our COVID response were needed to combat long-standing structural factors like racism and historical disinvestment in communities of color,” said Watkins-Tartt. “During the pandemic, Latino and Black populations were more likely to face exposure to the virus through more crowded homes and jobs in essential workplaces, and less likely to have health insurance and access to timely, high-quality care. These structural inequities caused large racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates. We worked to counteract these historical disinvestments through hyper-local outreach supporting vaccination and testing in communities most affected by COVID-19.”

Source: Alameda County Health Care Services Agency, March 2024

The historic disparities in health outcomes and likely negative outcomes for many people of color have been a focus not only of the state and county, but also of community partners like the Roots Community Health Center and Umoja Health, which are among many local groups that have done extra outreach to connect with these populations.

Two Grass Roots Champions: Roots and Umoja

Founded in 2008, the mission of Roots Community Health Center is to “uplift those impacted by systemic inequities and poverty.” As the founding executive director, Dr. Aboelata credits data sharing by the county and network of service providers for helping providers focus on the communities with the greatest need.

Roots has partnered with churches, barbershops and groups like the Brotherhood of Elders Network, an “intergenerational network of men of African ancestry,” and the African American Response Circle, a “collaborative of Black-led organizations and Black community leaders whose mission is to advocate for rapid action to address the disparate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black Oakland,” to coordinate services and messaging.

Roots has partnered with churches, barbershops and groups like the Brotherhood of Elders Network, an “intergenerational network of men of African ancestry,” and the African American Response Circle, a “collaborative of Black-led organizations and Black community leaders whose mission is to advocate for rapid action to address the disparate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black Oakland,” to coordinate services and messaging.

Roots stood up the region’s first COVID testing walk-up site in April 2020, and has conducted over 47,000 COVID tests so far, including approximately 3,500 nursing encounters for advice and treatment for those who tested positive. Beginning in January 2021, Roots began administering COVID 19 vaccinations and has provided over 21,000 vaccinations since. Roots has also provided more than 15,225 COVID test kits to the community.

Dr. Aboelata points to the city and county’s collaboration with nonprofits as the key to her group’s success. “The county ‘deputized’ community groups to do contract tracing because that’s where the trust is. The same goes for testing and mask distribution.” Roots has long partnered with Black barbershops to do blood pressure checks. When the shops were shut down because of the pandemic, many of the barbers became contact tracers, keeping their income intact while waiting to reopen. Now that the pandemic has eased, Roots works with a Barbers’ Advisory Council, which helps to oversee health screenings.

Umoja Health has been another critical player in reaching people who are particularly at-risk. Like Roots, Umoja centers much of its work in Oakland, but also works with surrounding counties. Umoja’s founding director, Dr. Kim Rhoads, is the Director of Community Engagement for the University of California-San Francisco Cancer Center and was working to bring cancer education and resources to Oakland, but says she got “derailed” by the pandemic. “Our partners contacted us, asking for help with the pandemic and we basically answered the call,” starting Umoja in Summer of 2020.

Dr. Rhoads is a firm believer in the advantages of working at the community level. “People want information from their neighbors, from their friends, from their networks,” said Dr. Rhoads. “They don’t want it from institutional leadership. They don’t trust it from institutions. So, bringing resources out into the community without labels—it didn’t say public health department; it didn’t say UC San Francisco; everyone was wearing the same t-shirt with the Umoja logo, and you didn’t know who was a doctor and who was a community volunteer. It was really an epiphany for me to realize that people want to be part of the solution. They want to take action, and when they see action happening, they want to get involved.”

Dr. Rhoads is a firm believer in the advantages of working at the community level. “People want information from their neighbors, from their friends, from their networks,” said Dr. Rhoads. “They don’t want it from institutional leadership. They don’t trust it from institutions. So, bringing resources out into the community without labels—it didn’t say public health department; it didn’t say UC San Francisco; everyone was wearing the same t-shirt with the Umoja logo, and you didn’t know who was a doctor and who was a community volunteer. It was really an epiphany for me to realize that people want to be part of the solution. They want to take action, and when they see action happening, they want to get involved.”

Umoja Health is a group of multi-sectoral partners whose mission is to build coalitions with the capacity to achieve health equity. The coalition connects people to resources and services, rather than serving as a health service provider or clinic. And, working with other groups in the county, Dr. Rhoads believes in a decentralized approach. “Black people are dispersed,” she said, “so the model for delivering services has to match that, and it also has to be decentralized, and so we started providing services in very curious places…We asked people where we should come. We wanted to show up where people already are—parking lots, stores, community events.” In September 2020, Umoja Health modeled the first pop-up services for COVID-19 testing and vaccination in Alameda County.

Churches were another vehicle for contacting people and represented a trusted source of information. “Faith leaders were important to us,” Dr. Rhoads said. “We knew people would listen to them. But initially, the churches weren’t ready, thinking this was going to be a short-term problem,” but once one of the small churches worked on COVID 19, other, larger, churches joined in, integrating messages about the pandemic in Zoom prayer circles and bible studies and setting up drive-through and walk-through testing sites serviced by Umoja Health. This care was followed by daily wellness calls to check on symptoms and recommend people to go to the doctor or emergency room. Umoja Health volunteers also provided groceries, transportation and other services to support isolation for those with the disease, to mitigate the spread and help them with self-care.

One of the other ways in which Umoja Health and its partners reached people was door knocking, using local residents as credible messengers to knock on their neighbors’ doors. “We used neighbors to do surveys, rather than academic researchers. We created partnerships with organizations that already have relationships with community,” said Dr. Rhoads. And, in so doing, the groups used a relational, rather than transactional, approach, which in turn has led to more sustainable community trust.

Focus on the Unhoused

From the beginning, Oakland, Alameda County, and the state focused many services on unhoused populations since they were often at-risk of contracting and spreading COVID 19. Much of this attention centered on providing non-congregate housing, with the Governor setting a goal of 15,000 rooms in hotels and other settings to be made available to the unhoused.

Within a nine-day period in March 2020, the state, in partnership with Alameda County, contracted with two hotels and a nonprofit agency to provide on-site services for 59 people initially. (Soon after, those two sites filled 391 rooms at capacity). Nearby counties added hundreds more beds in March and April, along with mobile testing, vaccination, and other services to alleviate symptoms.

Alameda County’s Office of Homeless Care & Coordination was named the point agency for homelessness services for the county and was “the first agency in the state with non-congregate housing for homeless residents with COVID or that were at highest risk to isolate them from others,” according to Alameda County Health Care Services Agency Director Colleen Chawla.

Oakland City Councilmember Dan Kalb credits services provided by the city and county for minimizing the pandemic’s effect on the unhoused, including food distribution, masks, and hand sanitizer, adding that a moratorium on evictions helped keep the number of unhoused people from rising.

Community Partnerships: Their Usual Approach

Watkins-Tartt is quick to point out that the county has always worked with community agencies, not just during COVID 19. “We have contracts with 45 community-based organizations with which we’ve had relationships since before the pandemic,” she said. “So, we were able to quickly work together around COVID.”

From its network of nonprofit partners, the county established a COVID Vaccine Community Advisory Group (CAG) early on, which included not only nonprofits, but also schools, cities, and individual residents. The CAG “helped shape and guide how we rolled out vaccines throughout Alameda County,” said Watkins-Tartt. “When the federal government wanted to set up the Coliseum for vaccines, community partners, including Dr. Rhoads, altered the plans to better fit the residents’ needs, as well as plans for mobile units. We vaccinated a lot of people and that was really because of the input from community partners.”

How We Integrate the Community Advisory Group (CAG) Across Vaccine Planning Efforts

Co-Chairs

Co-Chairs

Kimi Watkins-Tartt, Alameda County Public Health Director

Nestor Castillo, Public Health Commission/University Lecturer

Greg Hodge, KHEPERA Consulting/Brotherhood of Elders Network

Dr. Aboelata credits the city and county with a high degree of civic engagement, saying that the city council holds hybrid meetings and works with the community on homelessness and other issues and the county works with the community on other issues like mental health and crime prevention. An example is the county’s contracts with nonprofits for the delivery of mental health services and housing. Finally, she said, it was helpful to have the collaboration of the Oakland Unified School District and supporters like the East Bay Community Foundation, saying “the funders really stepped up, and we were fortunate to have that.”

Dr. Rhoads also feels that residents need long-term connections to providers. “People are used to transactional relationships in which professionals come into the community for a while with a specific agenda and then leave. Our goal was to establish year-round, non-transactional community engagement, and what that means is that we’re here even if there is no research study to do, we are here if you need a helping hand, or you need resources. Just reach out to us and we’ll do what we can; we’ll reach into our treasure-trove of resources and try to connect people to what they need.”

The county’s collaboration with nonprofits and residents was part of a foundation built into a 10-year visioning plan created in 2008, according to County Board of Supervisors member Keith Carson. “Collaboration intensified” following adoption of the plan, which “mandated cooperation with community groups, including neighborhood associations, nonprofits, labor, the League of Women Voters and others.”

Supervisor Carson said that the county’s visioning process was led by a futurist who foresaw a disaster like COVID 19, and helped the county prepare. “We created a system of two-way communication with residents that provided a platform for success,” said Carson. “Connecting with people who had lived experience, and continuously reevaluating how we’re interacting with residents created credibility so that we could best meet the needs of our residents.”

Having COVID 19 mandates in place was also a factor in helping Oakland and Alameda County achieve their goals, though this was also the case for many other locations nationwide. The state had vaccination mandates early-on for health facilities and the city adopted a mandate for city workers. Councilmember Kalb spearheaded passage of an ordinance in January 2022, long before other cities had done so, requiring proof of vaccination for visits to indoor public facilities and events. Oakland also worked with other cities in the region to be the first community in the nation to issue stay at home orders.

In the end, however, what distinguished the community and helped fuel their success was collaboration and trust. “There are incredible community champions in the county that have done terrific work,” said Dr. Pan, the state epidemiologist. And that work was built on a strong foundation of trust.

The Bigger Picture

A survey of local governments early in the pandemic lauded the nimble work of cities and counties, which to some extent relied on a playbook geared toward weather disasters. The study’s authors stressed the importance of collective efforts to address disasters, saying “collaboration for community benefits requires boundary spanning and inclusiveness—carrying out public purposes by engaging a wide net of participants—public, private and nonprofit.”

Several writers and studies have shown that countries with greater public trust, equity and social capital had fewer deaths from COVID-19. These are three of the ingredients of civic capital, a community’s capacity to solve problems and thrive. Civic capital is a key factor not only for community health, but for most quality of life measures we care about.

Jay S. Kaufman, a professor of epidemiology at McGill University, recently wrote in the New York Times that countries with lower COVID 19 deaths have been “distinguished by high levels of political cohesiveness, social trust, income equality and collectivism, like New Zealand, Taiwan, Norway, Iceland, Japan, Singapore and Denmark.” Although he included a caveat that these countries are also wealthier, wealth alone doesn’t seem to determine infection rates, which are quite high in wealthy countries like the U.S., U.K. and Luxembourg.

Kaufman cites a study published in late 2020 by researchers at Canada’s McGill and Carleton Universities that looked at COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries, concluding that income inequality, confidence in public institutions and civic engagement all contributed to reducing mortality. The study said that income inequality was a factor largely because of the prevalence of low-income workers in jobs likely to increase exposure to COVID-19. Confidence in public institutions was key to following testing, masking, and other mandates.

The positive aspects of civic engagement cited in the Canadian study relate back to the positive benefits of “social capital derived through civic engagement,” according to the report, as shown in various studies by the authors and other researchers. The authors say that this social capital is particularly helpful during a difficult time like the pandemic, when an appeal to people to work for the common good is part of the solution.

The relationship between civic engagement and the effects of pandemics or other disasters is also evident in a recent European study that showed that public trust is greater when governments are transparent, and people have an opportunity to be engaged. While this may seem self-evident, there have been few studies showing the correlation. And a finer detail of the study’s results is that transparency alone does not necessarily inspire trust; that trust is greatest when members of the public have an opportunity to participate in government decision-making.

The importance of civic engagement shown in the European study is likely a major reason for trust in local government remaining high, even as trust in the federal government has fallen. Particularly in the past 20 years, local governments have worked hard to increase transparency and community partnerships by working collaboratively with nonprofits and residents.

Alameda Public Health Director Watkins-Tartt emphasizes the importance of community engagement, saying that “being able to get at the neighborhood level to reach people and to create safety and access to services were critical to reach populations that were more vulnerable.” And that kind of focused effort has been important during a pandemic that has had uneven effects across populations, particularly for places like Oakland and Alameda County that have relied on the power of community for their success.

Doug Linkhart is President of the National Civic League and a former Executive Director of Denver’s Department of Public Health and Environment (formerly Department of Environmental Health).