By Doug Linkhart

The capacity of a community to create long-term health and well-being is much like the capacity for other public goods: it depends on the formal and informal relationships, networks and capacities that communities use to make decisions collaboratively and solve problems.

While some communities might start by creating better connections and communication among health care providers, this is only a small step in the right direction. Because health and well-being are more dependent on social, behavioral and economic factors, the involvement of residents and all types of organizations and institutions is key.

The National Civic League set out to map and measure the problem-solving capacity of communities, what we call civic capital, in 1986 using a tool called the Civic Index. This tool has been used and adjusted over the years, with the most recent edition released in early 2019. The Index lists seven components of civic capital, describing each one and offering questions for communities to consider as part of a self-assessment.

The Seven Components of Civic Capital

- Engaged Residents

- Inclusive Community Leadership

- Collaborative Institutions

- Embracing Diversity and Equity

- Authentic Communication

- Culture of Engagement

- Shared Vision and Values

This article applies these components to the capacity of a community to create health and well-being. Of particular interest is the need to address both physical health and mental well-being and look beyond direct services to the factors that underlie these conditions. This is an interest of the Well Being Trust, which lists seven “vital conditions for inter-generational well-being,”

- Basic Needs for Health & Safety

- Belonging & Civic Muscle

- A Healthy Environment

- Reliable Transportation

- Humane Housing

- Meaningful Work & Wealth

- Lifelong Learning

Similarly, it is important for communities that foster health and well-being to be attentive to the factors that most influence community health, the social determinants of health. The National Academy of Medicine estimates that only 10-20% of a person’s health is due to clinical care while the remaining 80-90% is due to social determinants of health. Healthy People 2020 lists five general categories of social determinants:

- Economic Stability

- Education

- Social and Community Context

- Health and Health Care (Access)

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

Clearly, there is much that local governance can influence within these five areas, and the seven components of the Civic Index comprise the infrastructure for doing so. What follows is a discussion of the components determining the capacity of local governance—not just government, but the full array of community stakeholders—for addressing health and well-being.

Engaged Residents

“Not about me without me” was a saying developed decades ago by organizations of people with disabilities and has been used by many communities since. In the arena of health and well-being this is particularly important since many studies show that most of a person’s health is guided by their behavior and environment, both of which can be influenced by an engaged population.

Engaging members of a community in health and well-being means reflecting their input in health plans, decision-making and program implementation. Community health assessments and plans often focus on health disparities and social determinants of health underlying those disparities. For this reason, it is particularly important to gain the active engagement of populations targeted for those improvements.

An example of resident engagement is the Southeastern San Diego Cardiac Disparities Project, which is improving the cardiovascular health of African Americans by partnering faith organizations and healthcare  providers. The project works with church congregations to develop “heart-healthy plans” to reduce heart attacks and strokes through nutrition education, exercise and health monitoring and tracking of participants’ blood pressure and weight. Some churches take a brisk “Gospel Walk” around their neighborhood once per month, returning afterwards to listen to a speaker talk about health, take their blood pressure and register their weight. This work is not only transforming the way parishioners think about their health, it is building trust among residents and health providers.

providers. The project works with church congregations to develop “heart-healthy plans” to reduce heart attacks and strokes through nutrition education, exercise and health monitoring and tracking of participants’ blood pressure and weight. Some churches take a brisk “Gospel Walk” around their neighborhood once per month, returning afterwards to listen to a speaker talk about health, take their blood pressure and register their weight. This work is not only transforming the way parishioners think about their health, it is building trust among residents and health providers.

Inclusive Community Leadership

Culturally appropriate leaders can be quite influential in fostering healthy behaviors and participation, whether it involves changing habits among teenagers or neighbors. These leaders can be role models, like the mayor of Oklahoma City who challenged himself and his community to collectively lose a million pounds, or information-providers, like the “promotoras,” community health workers used in places like Colorado to promote health among Spanish-speaking populations.

In Longmont, Colorado a pair of local tragedies led a group of 50 community members to form a coalition called Supporting Action for Mental Health (SAM), which hosted ten Community Conversations in just ten weeks to identify, and take steps to remedy, mental health issues facing the community. SAM has taken intentional actions to ensure that mental health work is inclusive, particularly for the monolingual Spanish-speaking/Latino community and for the LGBTQ community. This includes working with ten Latino/Hispanic “cultural brokers” who are actively involved in city programs and nonprofits in the community and help guide mental health outreach and services. SAM has trained 14 instructors in mental health first aid, including monolingual Spanish-speakers and LGBTQI+ youth. These individuals have helped to host community conversations and educational workshops with hundreds of people in all.

Collaborative Institutions

Few efforts to improve health and well-being could be successful without collaboration among the government, business, nonprofit and other sectors, as well as structures in place that facilitate such collaboration. Collective impact efforts typically create formal coalitions to address issues, often with specific outcomes in mind, like changes in the numbers provided by the annual Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count reports. Such efforts may be led by the local government, a broad nonprofit agency like the United Way or a local community foundation. Two features that are often lacking, however, is the involvement of residents and the creation and maintenance of a long-lasting structure for collaboration.

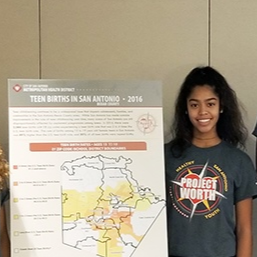

In 2010, then Mayor Julian Castro of San Antonio launched SA2020, a community-wide visioning process that identified eleven community goals tracked by 59 indicators, including reducing the county’s high teen birth  rate. The San Antonio Teen Pregnancy Collaborative was formed as a collaborative effort among public entities, community-based organizations and faith-based institutions. Since mental health is one of the underlying issues, Project Worth was created as a partnership with Communities in Schools to connect pregnant teens and teen mothers to mental health counselors. Additional intervention activities range from teen engagement initiatives like DreamSA to advocacy efforts like Health Futures of Texas’ Youth Advisory Council. Because of the targeted approach of holding each organization responsible for its own outcomes, the teen birth rate for Bexar communities is declining. Between 2010 and 2015, the teen birth rate for Latino teens, aged 15-19, went from 65.4 per 1,000 to 39.0, and the teen birth rate for African American teens, aged 15-19, also nearly cut in half from 45.6 per 1,000 in 2010 to 25.3 in 2015.

rate. The San Antonio Teen Pregnancy Collaborative was formed as a collaborative effort among public entities, community-based organizations and faith-based institutions. Since mental health is one of the underlying issues, Project Worth was created as a partnership with Communities in Schools to connect pregnant teens and teen mothers to mental health counselors. Additional intervention activities range from teen engagement initiatives like DreamSA to advocacy efforts like Health Futures of Texas’ Youth Advisory Council. Because of the targeted approach of holding each organization responsible for its own outcomes, the teen birth rate for Bexar communities is declining. Between 2010 and 2015, the teen birth rate for Latino teens, aged 15-19, went from 65.4 per 1,000 to 39.0, and the teen birth rate for African American teens, aged 15-19, also nearly cut in half from 45.6 per 1,000 in 2010 to 25.3 in 2015.

Embracing Diversity and Equity

Communities with strong civic capital recognize and celebrate their diversity. They strive for equity in services, support and engagement. This is particularly important for health and well-being, since these issues are generally experienced differently by different communities, whether by age, ethnicity, nationality, gender orientation or other factors. Using an equity lens to address each of the social determinants of health listed earlier—factors like education and economic stability—will clearly alleviate health disparities in a way that raises overall population health and well-being.

In 2004 Fremont, California, began an effort to improve the quality of life for the older adults among its large immigrant communities, which were not accessing services to the same degree as other populations. Following extensive outreach to community leaders, particularly leaders at churches, temples, mosques, and gurdwaras, Fremont’s Community Ambassador Program for Seniors (CAPS) was created.

In 2004 Fremont, California, began an effort to improve the quality of life for the older adults among its large immigrant communities, which were not accessing services to the same degree as other populations. Following extensive outreach to community leaders, particularly leaders at churches, temples, mosques, and gurdwaras, Fremont’s Community Ambassador Program for Seniors (CAPS) was created.

The CAPS program recruits and trains volunteers from the community to learn about city programs and options that are available to older adults. Since the initiation of the program, the city has trained about 250 volunteer ambassadors representing all of the city’s demographics, including Caucasian, Black, Hispanic, Indian, Chinese, Filipino and others. The ambassadors are trained to serve as liaisons between residents and various services, hold outreach events in their communities, provide education on how to access community resources and refer older adults to case managers as needed.

Authentic Communication

Healthy communities need credible, civic-minded sources of information presented in a way that residents can use. The myriad of information regarding health and well-being can be confusing, particularly to people from different cultures. With trust in government and other institutions declining, it’s important for communities to do what they can to present information in an unbiased and culturally appropriate manner.

Cornelius, Oregon found the need to change its communication styles after experiencing drastic demographic changes—going from a 70 percent white and 30 percent Latinx population to a 42 percent white and 53 percent Latinx population. In 2012, the city began a partnership with Centro Cultural to jointly co-host Spanish-speaking Town Halls to address issues of interest to Latinx community members. The city also provides all printed and online publications in Spanish and English. By creating partnerships with various Latinx organizations and churches in the county and encouraging Latinx participation on boards and commissions, the community has gathered input on issues like economic development, police reform and construction of a new library that has translated into much needed support for local programs.

Culture of Engagement

Involvement by residents, businesses, nonprofits and other stakeholders in health and well-being should be part of local culture—an expectation, not an afterthought. Some of the best methods for assuring this are showing long-term consistency in outreach to the community for each decision and plan and having a policy or requirement in place to assure engagement. As with many changes, starting a habit often leads to a change in values that becomes internalized as an expectation.

Tacoma, Washington, is one of many cities that has adopted a requirement to consider Health and Equity in All Policies. The county Health Department’s Board of Health adopted a resolution in 2016 that directs the city to consider health and equity in all their policies and decisions. An analysis tool was later created to guide managers in consulting with affected communities prior to adopting new policies or programs and examining the social, economic, and environmental costs and benefits of each action, helping to ensure equitable conditions for all populations. The city’s 2025 Strategic Plan also uses a health and equity lens in setting community goals and policies for the future.

Shared Vision and Values

Communities with a shared vision and values regarding health and well-being have a common foundation for addressing public matters. A shared vision and set of values can either come from an intentional process, like strategic planning, or be developed organically over time. In both cases, constant reinforcement is needed for long-term sustainability. It is also helpful to have a simple imperative, like “making our town the healthiest in the state” or “losing a million pounds.”

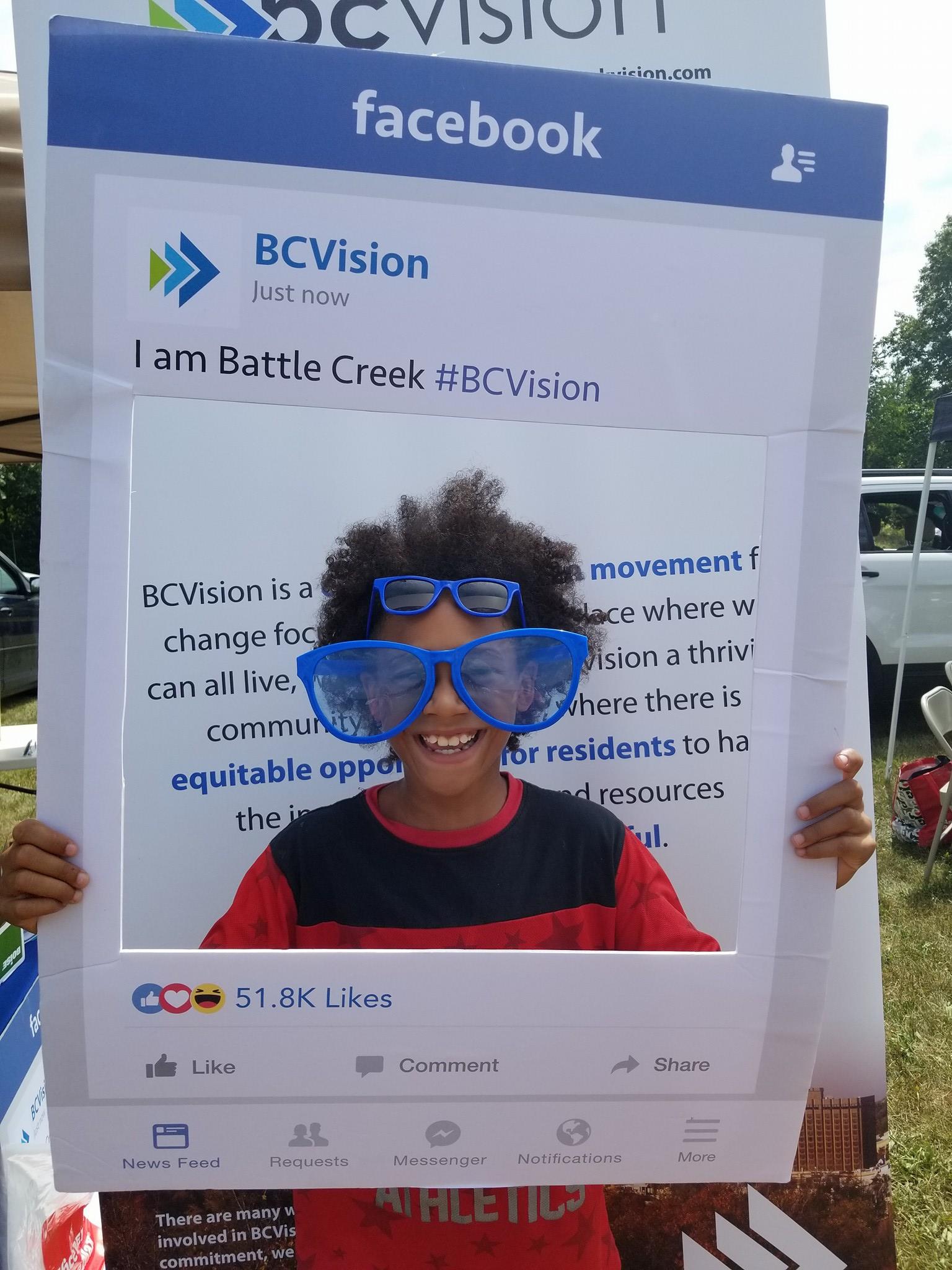

In 2015, Battle Creek, Michigan, launched BC Vision, a community-driven movement for change. Stakeholders included the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, members of the faith community, workforce and economic development agencies, government, business and schools, who gathered to engage residents and discuss how to spark transformation in Battle Creek. As part of its engagement efforts, the group (BC Vision) knocked on more than 30,000 doors, participated in dozens of community meetings, and spoke with thousands of neighbors to receive input from as many people as possible. The result was an overall goal to “create a thriving community where there is equitable opportunity for all community members to have the income, education and resources they need to be successful.” A variety of projects in local schools, city departments and nonprofit agencies were spawned by this vision to create better health, wellness and safety.

Summary

Civic capital for health and well-being doesn’t always assure actual outcomes. Many of the factors underlying these goals still lie in the hands of the individual. At the same time, by engaging the full community in work to combat the social determinants of health and creating a vision and culture of collective purpose, we can create better health and well-being one community at a time.

Doug Linkhart is president of the National Civic League.