By Amy B. Bloom

In August 2019, the Center for the Study of Citizenship at Wayne State University launched The Institute for Strengthening Communities, partnering with Oakland Schools, a regional educational service agency in Michigan serving 28 distinct local school districts. The premise of the Institute is this: Vital communities require informed and active citizens. Those communities are thick—located in physical space—and also relational, sustained, and rewarding. They enable people to engage with each other to accomplish that which they could not do alone. Thick communities are also defined by their opposite, thin communities, which are anonymous, ephemeral, transient, and transactional.

The Institute provided educators with training on how to use restorative practices, structured dialogue, and the deliberative process to strengthen their communities. These tools enable citizens to work together to identify and solve common problems. In the process, citizens build social capital networks and develop agency, voice, and a sense of belonging. They become more civically minded and resilient, both collectively and individually, as they decide together and act toward shared goals.

Why Focus on Schools?

The ability of community members to engage with each other in productive ways, even when they may disagree, is at the heart of democratic public life. If we want to be able to create the kinds of communities we want to live in, investment in learning the skills that enable citizens to do the work of citizens is essential. Today, however, a lack of models within the school environment is only compounded by what is amplified by the media. Talk news shows often devolve into talking points and shouting matches. Conflict tends to sell, so it is no surprise when that is what students see in the world. Cyber bullying is one by-product of not knowing how to talk. In an era of educational accountability to standardized tests, teachers and educational leaders have, to a large extent, lost their autonomy, voice, and agency. This loss makes it even more difficult for teachers to develop student autonomy, voice, and agency.

Over the years, as the accountability in education movement gained traction, schools responded in predictable ways. Focusing on what was measured (reading and mathematics), schools in Michigan lost sight of the primary purpose of public education. According to the Michigan’s teaching certificate, “The professional educator’s primary goal is to support the growth and development of all learners for the purpose of creating and sustaining an informed citizenry in a democratic society.” Yet, the accountability movement resulted in changing the purpose and shifting funding away from educating for democratic public life. In the process, schools became more disconnected from the broader communities they serve.

Let’s be clear, public schools have been under siege for over a decade. In Michigan, people “have voted with their feet” when their schools do not meet their child’s needs. Funding has dwindled. Most people who do not have children in their local school system are either disconnected, or they receive newsletters—a one-way communication strategy. Yet, public schools are place-based and have the opportunity to serve as the cornerstone of the community.

In January, 2018, the Michigan School Finance Research Collaborative completed Michigan’s first comprehensive school adequacy study, providing a roadmap to fixing Michigan’s broken school funding approach and making it fair for all students. The School Finance Research Collaborative is composed of a diverse group of business leaders and education experts from Metro Detroit to the Upper Peninsula who agree it’s time to change the way Michigan’s schools are funded. The collaborative’s public engagement committee is tasked with creating awareness and generating support for a more equitable school funding system. But simply publicizing the results of the study has not gained the traction leaders hoped. We approached members of the public engagement committee with the idea of using the deliberative process as a way to share information with the public about school funding, as people deliberated about improving public education. In this way, we obtained support from educational leaders.

Institute Structure

At its core, the Institute uses research-based practices to assist in responsible group decision-making. By focusing on community building and civic engagement through restorative circles, structured dialogue, and the deliberative process, participants experienced the power of collective decision-making by using diverse perspectives to address our most vexing shared problems.

For example, we used restorative circles as a practice of community building. Participants checked in with each other, built understanding of each other, and reflected on their learning together. In one activity, participants were asked to describe themselves with an adjective when they are at their very best. As each participant shared their strength, they learned about each other and saw the collective strength of the group.

Through the Center’s Citizen Dialogue process, participants engaged in structured dialogues about controversial issues. Applied to bifurcated issues defined by others, Citizen Dialogues are designed to peel away the layers in order to address the deeper issues that underlie a problem. There are several rounds in which each participant has up to one minute to talk. There is no crosstalk; participants are asked to make notes, so they can address an issue when they have the floor. Each Citizen Dialogue starts with one’s individual perspective on the issue and an explanation of how their experience informs their position. The final part of this process is for reflection for the individual and the good of the group.

We used several issue advisories and issue guides from the National Issues Forum Institute to engage participants in deliberative forums, allowing participants to select the issues. Once educators experienced the power of the deliberative forum, they wanted to learn more. Given that our goal was to hold deliberations around public education as a way to strengthen the school community internally and as a public institution, it was imperative that participants understood the entire deliberative process, outlined by the Charles F. Kettering Foundation.

Concern collecting or “naming the issue” in public terms is the first step in the deliberative process. As such, it was the first task that participants undertook. Naming is critical for two reasons: it focuses on people talking with others (social networking) and allows people to describe or “name” the issue in their own terms, bringing their experiences into defining the problem. While we considered using technology in the naming phase, person-to-person concern collecting had more potential to create and expand participants’ social networks. We decided that this was more important than the quantity of the data collected.

After the first three days of the Institute, there was significant growth of participants’ agency, voice, and sense of belonging. We saw their trust in one another grow. They gained confidence in being able to engage with those who they had previously avoided. They also began to see this work as a promising approach to authentically connect their institutions to the broader communities they serve. The reflections below demonstrate the impact of the Institute in developing thick communities.

“This institute gave me hope about my deep beliefs but needed to find my people to do this work with. I am encouraged in where I hope our generations are going.”

“This did make me more hopeful about what’s possible and the work that is being done in schools and out of schools.”

“It has extended my beliefs to move to a more active role in engaging our communities.”

“[Educating for democracy] means educating our students/community so that we would want to be their neighbor. It means teaching the practices so that our students can be engaged citizens in their community through talking to their neighbors, participating in public forums, and volunteering to make their communities better.”

“Change begins with us! When we can start at the grass roots, we can close the gaps through connection and ownership (Agency, Voice, Belonging).”

An Authentic Approach to Capacity Building

The summer work set the stage for serious growth of participants’ ability to apply the training to their own contexts. Two well-resourced school districts in Oakland County, Bloomfield Hills Schools and Birmingham Public Schools, joined the Institute, along with 482 Forward and Detroit Future City. Detroit Future City (DFC) brought Citizens Dialogues to their efforts at community outreach around the Detroit Reinvestment Index through a capacity building grant from the Community Foundation of Southeastern Michigan. The result was a transformation in how DFC communicated with residents.

Instead of the traditional information session where information holders share what they know and individual listeners ask questions, we engaged community members in a Citizen Dialogue around the index. Through the dialogues, citizens found common ground and built social networks. A telling sign of this was the willingness of citizens to stay afterward to exchange contact information with people they had just met. Detroit Future City has since enlisted the Center for the Study of Citizenship’s help in using dialogue and deliberation to set the direction for their rental and homeowner compact groups in the city.

In order to create an authentic project for students to use deliberation to improve their schools, the Center partnered with USC Shoah Foundation to introduce teachers to the Stronger than Hate Challenge. The Stronger than Hate Challenge encourages students to take action to counter hate in their environment and requires a video essay of what students did to counter hate and a reflection on their impact. This project provides an opportunity for teachers to engage students in collective decision making (deliberation) in order to determine the civic action necessary to improve their school.

Prior to the Coronavirus pandemic, the culminating training of the Institute was set to occur on April 20, 2020 when participants were to facilitate both a Citizen Dialogue and a deliberation with authentic audience to hone their facilitation skills in a one-day teacher training, “How Should We Welcome Newcomers to Our Community?” Eager to prepare for this challenge, teachers at Seaholm High School sought to find unique ways to engage students in deliberative forums on public problems. They scheduled four deliberations with students and planned to use topics that would resonant with students (Land of Plenty, Bullying, and Driverless Vehicles). Watching them as they created space for deliberation by navigating their system has been nothing short of inspiring. Teachers are natural facilitators and leaders if we just give them the chance. Although these activities have been placed on hold, Institute leaders are considering using Common Ground for Action, an online platform, to continue this work.

Lessons Learned

Invest in Transformative Change: For students to be exposed to deliberative politics, transformative change within the educational system is required. Transformative change requires that educational leaders and teachers are willing (think it is important), ready (know what it is and where to use it), and able (have the support and resources) to implement democratic practices. If we want to provide opportunities for students to engage in deliberative politics, we must begin with educators, school administrators, and school boards. It is for this reason that Wayne State University’s Center for the Study of Citizenship focused its first effort on schools.

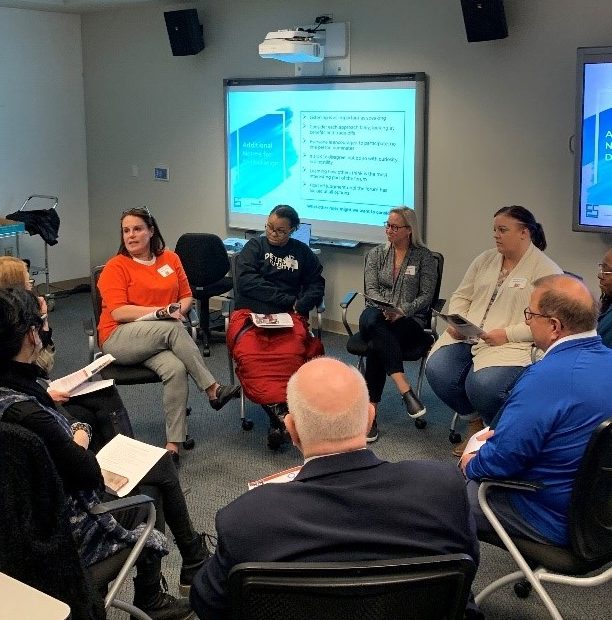

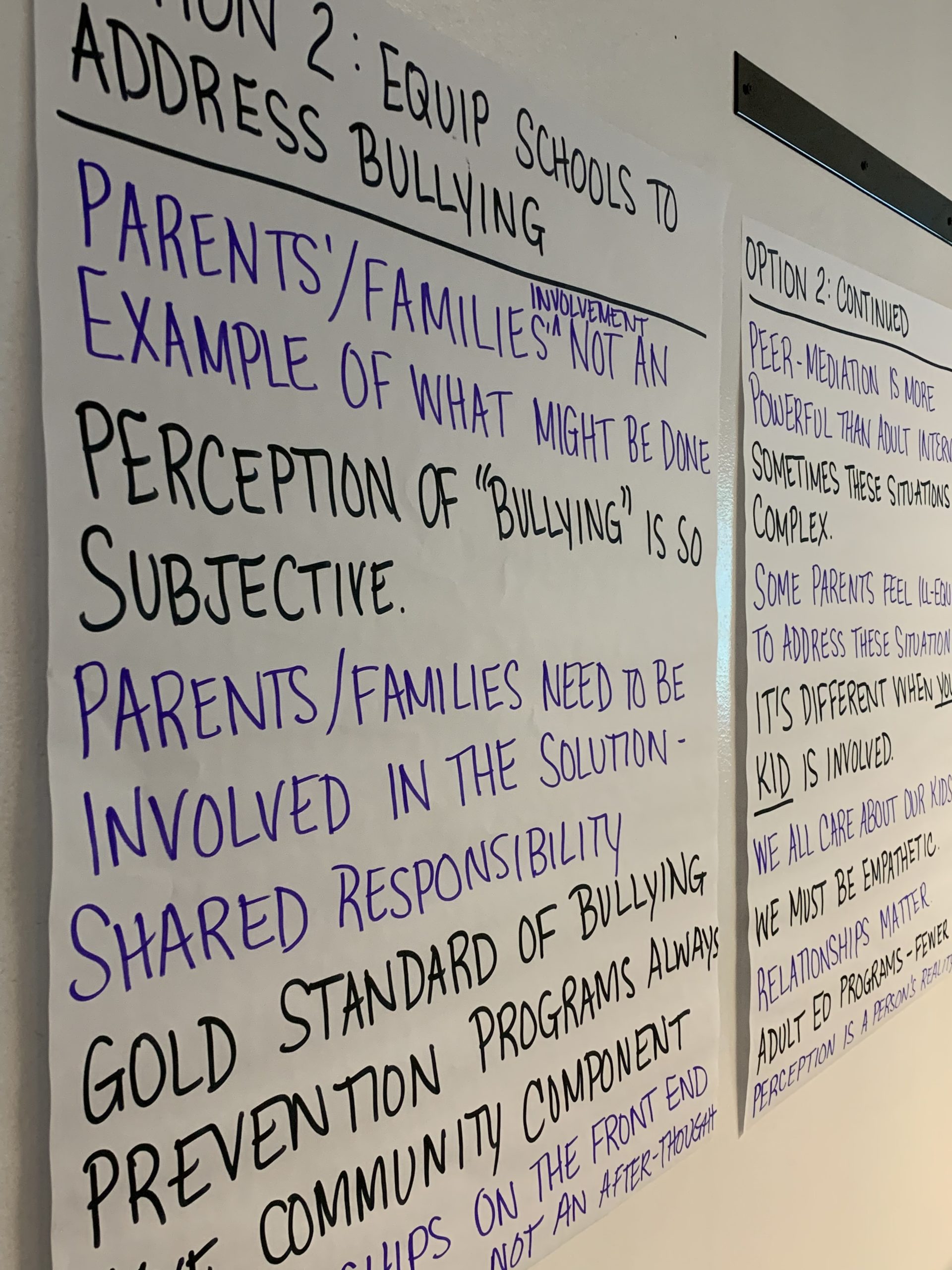

Build a Diverse Team: We sought teams from districts that included at least two teachers, a building leader, central office personnel, and at least one board member. From there, we asked teams to add members that might lead to new perspectives. The combination was powerful. Teachers, administrators, and board members found common ground and constructed new approaches to perennial problems by learning how certain policies impact others in the school system. This combination created social connections and social capital as teams worked together as equals and learned the value of each other’s perspectives. In one school, we had English, mathematics, science, and Spanish teachers join in. The  team of six became a team of 16. This allowed us to engage them in a deliberation around bullying that resulted in educators identifying additional actions they could take to improve the school’s approach to bullying behavior.

team of six became a team of 16. This allowed us to engage them in a deliberation around bullying that resulted in educators identifying additional actions they could take to improve the school’s approach to bullying behavior.

Citizen Dialogues Are A Good First Step: Since the Citizen Dialogue process is easy to teach, it works well in classrooms. Teachers report that selecting the students that talk the most for the role of facilitator seems to increase participation of all members. The protocol heightens students’ listening skills and contributes to building voice and a sense of belonging among group members. Citizen Dialogues can be mapped onto social-emotional learning core competencies and lay the groundwork for a deeper dive, which is deliberation.

Introduce Deliberation as a Means of Collective Problem-Solving: Educators and educational leaders saw value in all aspects of the deliberative process, from concern collecting to action. Deliberation fosters social-emotional learning, creates agency, voice, and a sense of belonging among participants. Significantly, it provides an authentic way for students to engage in multi-generational learning and holds promise for connecting schools as public places to their broader community.

The Deliberative Process Strengthens Our Schools and Our Communities: In order to create the kind of communities we want to live in, schools need to be proactive in connecting to the broader community. Schools have become transactional institutions to many. Schools leaders are eager to find ways to build support for public schools. Dialogue and deliberation provide authentic opportunities for students to engage with the public and support intergenerational learning. The use of dialogue and deliberation with the broader community can build social capital and civic engagement with people who may not be naturally connected with the school. Dialogue and deliberation allow schools to learn from community members, as well as community members from one another.

Outcomes and Impact

After the three-day kickoff last summer, we saw movement on almost every measure as participants became more ready, willing, and able to implement restorative and democratic practices. Since restorative and democratic practices are processes that teach social emotional core competencies, we also measured participants’ understanding of social-emotional learning. At the beginning of the Institute only 20 percent of participants strongly agreed with the statement, “I understand how restorative, dialogue and deliberative practices support students developing social emotional learning.” By the end of the three-day kickoff, 100 percent of participants strongly agreed with this statement. Likewise, participants response to the statement, “I am able to use restorative, dialogue, and deliberative practices to support students developing social emotional learning” grew from 30 percent neither disagree or agree and 70 percent somewhat agree to 100 percent strongly agree.

We saw similar growth with participants’ understanding of agency, voice, and sense of belonging, and how restorative and democratic practices support students in developing them. With respect to agency, only 10 percent of participants agreed with the statement, “I am able to use restorative dialogue, and deliberative practices to support students developing agency” at the beginning of the Institute. After three days of training, that number soared to 91 percent strongly agree and 9 percent agreeing. With respect to voice and sense of belonging, the percentages grew to 100 percent strongly agree on every measure.

We then sought to measure the connection between social-emotional learning, agency, voice, and belonging and civic health. By the end of the three days, 100 percent strongly agreed that improving students’ and their own social-emotional learning, agency, voice and belonging will enable them to become thoughtful, active, and compassionate citizens.

Conclusion

Taken together, restorative practices, dialogue, and the deliberative process are essential tools for self-government. They build agency, voice, and a sense of belonging to something bigger than ourselves. They are processes that improve the civic health of communities by enabling citizens to:

- Forgive and repair harm among community members and to remain in good standing in our community among our neighbors;

- Listen and find value in different perspectives in how our neighbors see and define a problem;

- Develop a willingness to engage to find common ground with those whom we disagree; and

- Act with others for a common purpose that will improve our world.

That is what living together is all about. If we want to prepare the next generation for democratic public life, students need to see people engage in these types of democratic practices. Providing educators with the skills to engage in dialogue and deliberation not only holds promise of intergenerational learning for a community but can also improve people’s faith in a public institution – their public school.

(Author’s Note: Marc Kruman, Director of the Center for the Study of Citizenship and Professor of History at Wayne State University, provided critical support for the Institute and editorial support for this article. The Institute was made possible by the hard work of Julie McDaniel-Muldoon, Safety and Well-Being Consultant at Oakland Schools, and Kelly Carey, Curriculum Production Consultant at Oakland Schools. Michael Yocum, Oakland Schools Assistant Superintendent, and Steven Snead, Supervisor of Curriculum and Assessment at Oakland Schools, also provided support and encouragement for the Institute.)

Amy Bloom is a research scholar-in-residence at Wayne State University’s Center for the Study of Citizenship and a former social studies consultant for Oakland Schools