By Doug Linkhart

What makes some communities better able than others to solve the tough social, political, economic, or physical challenges they face? This was a question the National Civic League set out to answer in 1986. On-the-ground research revealed a set of factors that we call civic capital– the formal and informal relationships, networks, and capacities that communities use to make decisions collaboratively and solve problems.

“A common thread in successful communities is the ongoing struggle through formal and informal processes to identify common goals and meeting individual and community needs and aspirations,” noted former National Civic League President John Parr in 1993.1

This common thread is civic capital, a term that National Civic Review authors William Potapchuk and Jarle P. Crocker once defined as “the collective civic capacities of a community, the currency supporting collaborative strategies that pursue innovative programs and forge new relationships to build a future with better results for children and families.”2

Somewhat like social capital, but not to be confused with financial capital, civic capital can be found in all sorts of communities, not just the most affluent, educated, or advantaged. While myriad other factors contribute to community progress, civic capital is the core factor identified by the National Civic League as the primary explanation for long-term community success.

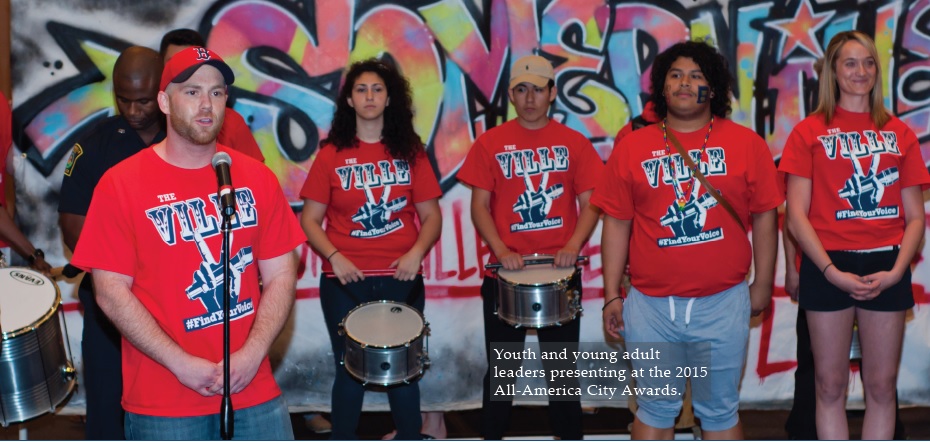

At the National Civic League, we know of many communities with an abundant supply of civic capital. The All-America City program has recognized over 500 of these communities during the past 69 years. All have varying degrees of civic engagement, collaboration, and leadership and have been able to tackle tough issues in a sustainable manner—by bringing everyone to the table and creating equity.

In January 2019 the National Civic League will release the fourth edition of the Civic Index, a self-assessment tool consisting of a set of questions that provide a framework for discussing and measuring a community’s civic capital. Since it was first developed in 1986, many communities have used the Civic Index to better understand their civic strengths and to identify gaps or areas in need of further attention, soliciting community input to create a baseline measure of their civic capital and monitor progress over time as they work to enhance their internal capacity. The Civic Index is intended to be subjective and  qualitative; how a community ranks on the index depends on the views of residents and other community stakeholders. And, importantly, the rankings by different parts of the community should not be averaged, lest the differences among various parts of the community be lost.

qualitative; how a community ranks on the index depends on the views of residents and other community stakeholders. And, importantly, the rankings by different parts of the community should not be averaged, lest the differences among various parts of the community be lost.

The full Civic Index is available from the National Civic League. This Index describes the seven components of civic capital, provides examples of each, lists the 32 questions that are used to gauge each component and provides ideas on how to use the index. What follows here is a synopsis of the seven components and their presence in various communities.

Engaged Residents: Residents play an active role in making decisions and civic affairs.

“The health of a democratic society may be measured by the quality of functions performed by private citizens,” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

Communities are more likely to thrive when residents, businesses, and other stakeholders play active roles in shaping decisions and taking action. The notion that “government cannot do it alone” was an important part of de Tocqueville’s message, and it is increasingly evident in times of limited resources. Activities to address particular issues are more likely to be sustainable when community members are involved in their development and implementation.

El Paso, Texas, has always enjoyed significant resident involvement in neighborhood associations and civic affairs. It has worked for the past two decades to encourage greater diversity in that participation through a Neighborhood Leadership Academy, a 20-week educational program to develop non-traditional community leaders. The city also sponsors a small grants program for neighborhood associations and has adopted a policy that requires that board and commission members include residents who will be impacted by the decisions made by those entities, particularly low-income residents, people over the age of 55, people with disabilities, and the homeless.

Inclusive Community Leadership: The community actively cultivates and supports leaders from diverse backgrounds and with diverse perspectives.

Communities with good civic capital have leaders that represent all segments of the population, along with abundant opportunities for leadership development. Such communities often have formal leadership programs and generally have a variety of boards, commissions, and community positions in which rising leaders can play a role. Most important, it should be possible for anyone to rise to a leadership position. As Martin Luther King, Jr. once said:

Everybody can be great, because everybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve…You don’t have to know about Plato and Aristotle to serve.”

Faced with a boom in newcomers from other countries, Beaverton, Oregon, has gone to extra lengths to ensure that immigrants, refugees, and communities of color are involved in decision-making. The Beaverton Organizing and Leadership Development (BOLD) identifies, engages, and trains emerging leaders from these communities and provides an in-depth orientation to city government and opportunities for engagement. BOLD has trained over 100 participants to date, with more than half of participants engaging in supplemental activities after graduating and a significant percentage taking on volunteer roles ranging from short-term to multi-year commitments.

Collaborative Institutions: Communities with good civic capital have regular collaboration among the government, business, nonprofit, and other sectors, as well as structures in place that facilitate such collaboration.

Collaboration strengthens the ability of communities to solve problems. As Bruce Katz and Jeremy Nowak discuss in The New Localism, local communities have become more powerful players in solving national issues because they have rediscovered the power of community collaboration. “Leadership by the public, the private or the civic sector alone is often not sufficient to tackle the multidimensional nature of challenges today,” write Katz and Nowak.3

In Fall River, Massachusetts, leaders recognized that no single agency could address the myriad issues facing the community’s young people. Only through collaboration and partnership could the community address such intertwined and complex issues. The School-Community Partnership (SCP) was created with the collective power of more than 30 agencies providing a variety of services to youth. The Mayor/Superintendent’s Attendance Task Force educated the community about the importance of attendance, reducing truancy. The collaboration also resulted in a new Youth of the Year award program, a Youth Violence Prevention Initiative, and a Youth Candidates Night.

Embracing Diversity and Equity: Communities with healthy civic capital recognize and celebrate their diversity. They strive for equity in services, support, and engagement.

U.S. cities and towns are becoming more diverse, and that diversity requires new strategies for civic engagement. Between 1980 and 2010, 98 percent of America’s metropolitan areas and 97 percent of micropolitan areas became more racially diverse. That diversity often leads to disparities in education, health, economic prosperity and other factors. For these communities to have sustainable prosperity, these inequities must be addressed. As shown in recent research from Katharine Bradbury and Robert Triest, greater equality of opportunity yields greater overall economic growth. Communities that involve all populations in local governance and address inequities will find longer-lasting solutions to key issues, including economic prosperity.4

In 2015, Battle Creek, Michigan, launched BC Vision, a community-driven movement for change. Stakeholders included the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, members of the faith community, workforce and economic development agencies, government, businesses, and schools—all who gathered to engage residents and discuss how to spark transformation in Battle Creek. As part of its engagement efforts, the group (BC Vision) knocked on more than 30,000 doors, participated in dozens of community meetings, and spoke with thousands of neighbors to receive input from as many people as possible. The result was an actionable, long-term economic development plan that included neighborhoods and community members who, historically, have had less access to resources that lead to prosperity.

Authentic Communication: Healthy communities need credible, civic-minded sources of information presented in a way that residents can use.

The quality of information and communication in a community dramatically impacts its civic health. Authentic communication is more than just the presence of trusted, civic-minded news-gathering entities (though that is critical). In communities that prioritize authentic communication, organizations provide information in multiple ways to meet the needs of residents, including through face-to-face meetings, print, and social media. In these communities, residents can have effective, two-way communication with nonprofits, the city, and other key institutions in their own language and preferred style, with the expectation that, when they share their questions, comments or concerns, they will receive an appropriate response.

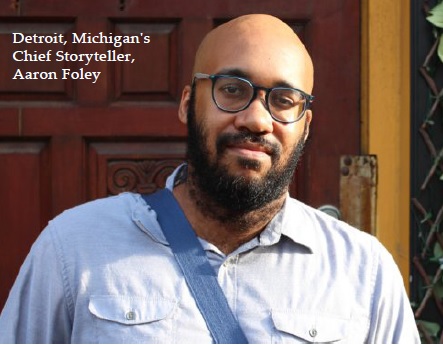

Detroit, Michigan, supplements news from local media with its own “chief storyteller.” Aaron Foley, a veteran African American journalist and Detroit native, helps provide residents with a fuller picture of their own community by providing context and depth to people’s understanding of the real Detroit through video and other multimedia, multiplatform efforts. As Foley explains:

“I make it my mission to spotlight a lot of different communities that don’t normally get mainstream media coverage. So we’re talking about our LGBTQ communities, our Muslim communities, and our immigrant communities and also, people of color, period.”

Culture of Engagement: Involvement by residents, businesses, nonprofits, and other stakeholders in every aspect of civic affairs should be part of local culture—an expectation, not an afterthought.

De Tocqueville marveled at how Americans formed associations for “the smallest undertaking,” saying that citizens stood ready to tackle any need. Communities with a strong culture of engagement work to listen to, and learn from, residents in ongoing conversations and leverage those insights to shape the way programs are designed, administered, and executed. Developing such a culture requires consistent behavior over time, such as always consulting with various groups prior to addressing a particular challenge. It also involves making room for others to lead, take action, and get credit.

Involvement in civic affairs is a way of life in Rancho Cordova, California, a city of more than 70,000 residents that was designated an All-America City in 2010. The Cordova Community Council works with the city and the chamber of commerce to organize activities throughout the year, including holiday celebrations and parades, an annual Community Volunteer Awards event, an annual Kids Day in the Park, and the Rancho Cordova Fest that celebrates the different cultures represented in the city. The Council also holds community meetings on occasion regarding issues facing the community and sponsors the Mayor’s State of the City address, an evening event that typically draws over 300 people. Community Council members also volunteer in a variety of capacities, from working on city committees and neighborhood beautification efforts to cleaning debris from storm gutters.

Shared Vision and Values: Communities with shared values and civic pride have a common foundation for addressing public matters.

A shared vision and set of values can either come from an intentional process, like strategic planning, or be developed organically over time. In both cases, constant reinforcement is needed for long-term sustainability. Many areas engage in community visioning processes; the key to developing a shared vision and values is to reach all parts of the community and end with a simple, memorable vision or slogan, like “the city of brotherly love.” A collectively-held vision and set of shared values can also come from a collectively-defined culture and sense of civic ownership that might result in statements like “that’s not how we do things here” or “the (city’s name) way.”

San Antonio, Texas, conducted one of the more extensive visioning processes, launching the SA2020 initiative in 2010. Through a series of public meetings, online chat sessions, and surveys, nearly 6,000 residents helped develop a framework, define community results and identify measures of success. The first SA2020 report was released in 2011, with updates occurring every few years since that time. To guide the strategy into implementation, SA2020 became an independent, non-profit organization and a collaboration among the City, 133 non-profits, seven major corporations, the San Antonio Area Foundation, and United Way. Of the 61 indicators currently being tracked, 70 percent are trending better today than they were in 2010. This includes progress toward high school graduation rates, per capita income, health care access, teen birth rate, and diabetes rate.

Bringing It All Together: Three Cities with Civic Capital

In looking for concrete example of communities with abundant civic capital, three communities come to mind: Longmont, Colorado; Somerville, Massachusetts; and Dubuque, Iowa. All three have won recognition as All-America Cities, whose main criteria is the use of civic engagement to build thriving, equitable communities. And all three have the long-term capacity for problem-solving and community-building that create a good quality of life for all residents.

Longmont, Colorado

Longmont, Colorado, has invested in civic capital by creating a comprehensive engagement plan, engaging Spanish-speaking residents, supporting residents to take action in their own neighborhoods, and developing inclusive leadership opportunities. Beginning with a neighborhood leadership program in the 1990’s, the city revamped its outreach efforts in the early 2000’s to ensure neighborhood input on all city actions.

Longmont, Colorado, has invested in civic capital by creating a comprehensive engagement plan, engaging Spanish-speaking residents, supporting residents to take action in their own neighborhoods, and developing inclusive leadership opportunities. Beginning with a neighborhood leadership program in the 1990’s, the city revamped its outreach efforts in the early 2000’s to ensure neighborhood input on all city actions.

While Longmont’s population is 26 percent Latino, this population was often missing in city outreach efforts. The city began hosting focus groups reflecting the demographics of Longmont in age, gender, income, race and education level, working with Latino advocacy groups to reach residents at social service outlets, festivals, teen mom support groups, and various chamber of commerce events. The city also put into place a bilingual policy to hire and train city workers in Spanish. The city helps build capacity by providing grants to fund improvement projects and events that explore the benefits of knowing your neighbors, leading to safer, healthier neighborhoods. Longmont has worked to provide leadership opportunities to the full diversity of its residents, providing training programs and scholarships to increase involvement among people of color on boards and commissions. In addition, the local school district has a leadership and participation training program that has more than 2,000 participants, winning a national award from IAP2 in 2014.

Somerville, Massachusetts

In Somerville, civic engagement isn’t just a strategy; it’s an integral part of the fabric of the community. As Somerville has changed from a largely white, working- and middle-class community to a dynamic, diverse, and vibrant urban hub of arts and innovation, so has the need to communicate and engage with a diverse constituency. Today, Somerville is an eclectic mix of blue-collar families, young professionals, college students, artists, and recent immigrants from countries as diverse as El Salvador, Haiti, and Brazil. One-third of residents are foreign born, and more than 52 languages are spoken within the public schools.

The city engages residents in numerous ways, from traditional town hall meetings to making data readily available to residents through its ResiStat initiative and utilizing their feedback to inform future policy. The city’s 20-year comprehensive plan, “SomerVision,” was developed through a three-year community process that incorporated the ideas of hundreds of residents, businesspeople, local organizations, and key stakeholders. It contains more than 40 strategic goals for Somerville’s future and serves as the basis for planning and community development projects and policies.

In 2013, the City of Somerville expanded its non-English language outreach with SomerViva!, its immigrant outreach program, which consists of native speakers of Spanish, Portuguese, Haitian Creole, and French who serve as liaisons between the city and the largest immigrant communities. The city also provides leadership and other training programs for residents of all income, education, and age levels, including a program for Latino immigrants called Gente Ponderos (Emerging Leaders). This leadership skills program is conducted in Spanish for Latino residents and teaches how decisions are made within local government and how residents can help shape those decisions through advocacy.

Dubuque, Iowa

Civic engagement has played a major role in helping Dubuque, Iowa, recover from a collapsed economy in the late 1970s and 1980s. Beginning with Envision 2000, a visioning process involving over 5,000 citizens, Dubuque established and accomplished goals to redevelop their industrial river basin, develop new amenities like a river walk and water park, and attract new businesses. A follow-up process, Envision 2010, resulted in 10 Big Ideas for addressing service and infrastructure needs, many of which have now been achieved, thanks to the work of a committee of over 100 volunteers working to make the ideas a reality.

Civic engagement has played a major role in helping Dubuque, Iowa, recover from a collapsed economy in the late 1970s and 1980s. Beginning with Envision 2000, a visioning process involving over 5,000 citizens, Dubuque established and accomplished goals to redevelop their industrial river basin, develop new amenities like a river walk and water park, and attract new businesses. A follow-up process, Envision 2010, resulted in 10 Big Ideas for addressing service and infrastructure needs, many of which have now been achieved, thanks to the work of a committee of over 100 volunteers working to make the ideas a reality.

In 2006 the city created Sustainable Dubuque, a city council–adopted, community-created, and citizen-led initiative that spans topics such as energy use, clean air and water, healthy living and healthy local foods. With leadership from the Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque, community residents became engaged in a variety of efforts to improve sustainability that made a measurable difference in water use and other indicators. A similar effort in 2012 engaged local residents in improving grade-level reading, an effort for which the city received an All-America City designation that year.

In 2012 the city increased its civic resources by hiring their first Community Engagement Coordinator and beginning a citizen academy named City Life, with particular outreach to the city’s immigrant community. This office also helped create Inclusive Dubuque, a collective impact model involving more than 50 network partners whose goal is “to have a community where people feel respected, valued, and engaged.” The initiative collects data on diversity and equity regularly and has created an Equity and Engagement Toolkit for use by city agencies and other organizations to use in helping the city be a welcoming place.

Summary

Civic capital doesn’t always assure that a community will be prosperous or that residents will be happy. As Hampton, Virginia, City Manager Mary Bunting, says:

“Engagement never guarantees that everyone will be happy with the result. That utopia doesn’t exist. However, engagement does produce better decision-making and, more importantly, better feeling about the process used to make decisions. When residents know they have (and how) to make a choice to influence decision-making, they inevitably feel better about it.”

At the same time, our experience with communities during the past 125 years of the National Civic League’s existence and the 70 years of recognizing All-America Cities is that communities that have the qualities measured by the Civic Index are more able to address difficult issues, withstand challenges, and maintain a high quality of life. Because so many issues facing communities disproportionately affect certain populations within a city, inclusion and equity are particularly important in assuring the well-being of the community as a whole.

Nearly a hundred years ago, Justice Louis Brandeis, a one-time member of the League’s executive committee, called states “laboratories of democracy.” That mantle has now been passed to the local level as cities, counties, towns, and other local communities innovate and create regional or national networks to tackle such issues as climate change, health, education and economic prosperity.

At the same time, local governments cannot solve problems on their own. As Bruce Katz points out in The New Localism, community problem-solving depends on “multi-sectoral relationships,” with government often serving as a convener or catalyst. What happens next depends on the civic capacity of the particular locality. It is the communities with civic capital—the full engagement and collaboration of its residents, businesses, nonprofits, and other stakeholders—that have the resources and persistence to successfully address difficult issues and build a sustainable future.

Click here for a copy of the new revised Civic Index.

Doug Linkhart is president of the National Civic League.

1 John Parr, “Civic Infrastructure: A New Approach to Improving Community Life,” National Civic Review, Summer 2008, 18.

2 Jarle P. Crocker, Jr. and William Potapchuk, “Exploring the Elements of Civic Capital, National Civic Review, Fall 1999, 175.

3 Bruce Katz and Jeremy Novak, The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive in the Age of Populism, 2018.

4 K. Bradbury and R. Triest, “Inequality of Opportunity and Aggregate Economic Performance,” Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, May 2016, 178-201.