By Janine Vanderburg

A perplexing paradox persists in the United States. Throughout 2022, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data reported anywhere between 10 and 11 million unfilled jobs in the country. In my home state, the governor reported at the unveiling of Colorado’s Talent Pipeline Report that there are two jobs available for every person who is unemployed. We know that this has devastating impacts for our local and regional economies. Growth is stifled, and businesses close.

The paradox? Older workers want to work and are not being considered for open positions. Workforce development centers report large numbers of people aged 50+ seeking services. At Changing the Narrative, we hear constantly from older jobseekers who believe they are not being given a chance for open positions, and workshops that we facilitate with workforce development centers on Success Strategies for Jobseekers 50+ are always filled.

Data from AARP and others suggest that rampant workplace age discrimination may be at play.

A 2021 survey by AARP found that 78 percent of people aged 40-65 had either seen or personally experienced age discrimination in the workplace. Resume Builder surveyed 800 hiring managers across the United States and found that 38 percent of them admitted to reviewing applications with age bias. While the myth of a pandemic-related “great retirement” among older adults has permitted, research by the Schwartz Center Economic Policy Analysis shed light on what actually occurred—a “great shedding.” Older workers were forced out of the workplace; most of the so-called “retirements” happened after older workers who had been pushed out were unable to find other employment.

So why is this important? What are we missing?

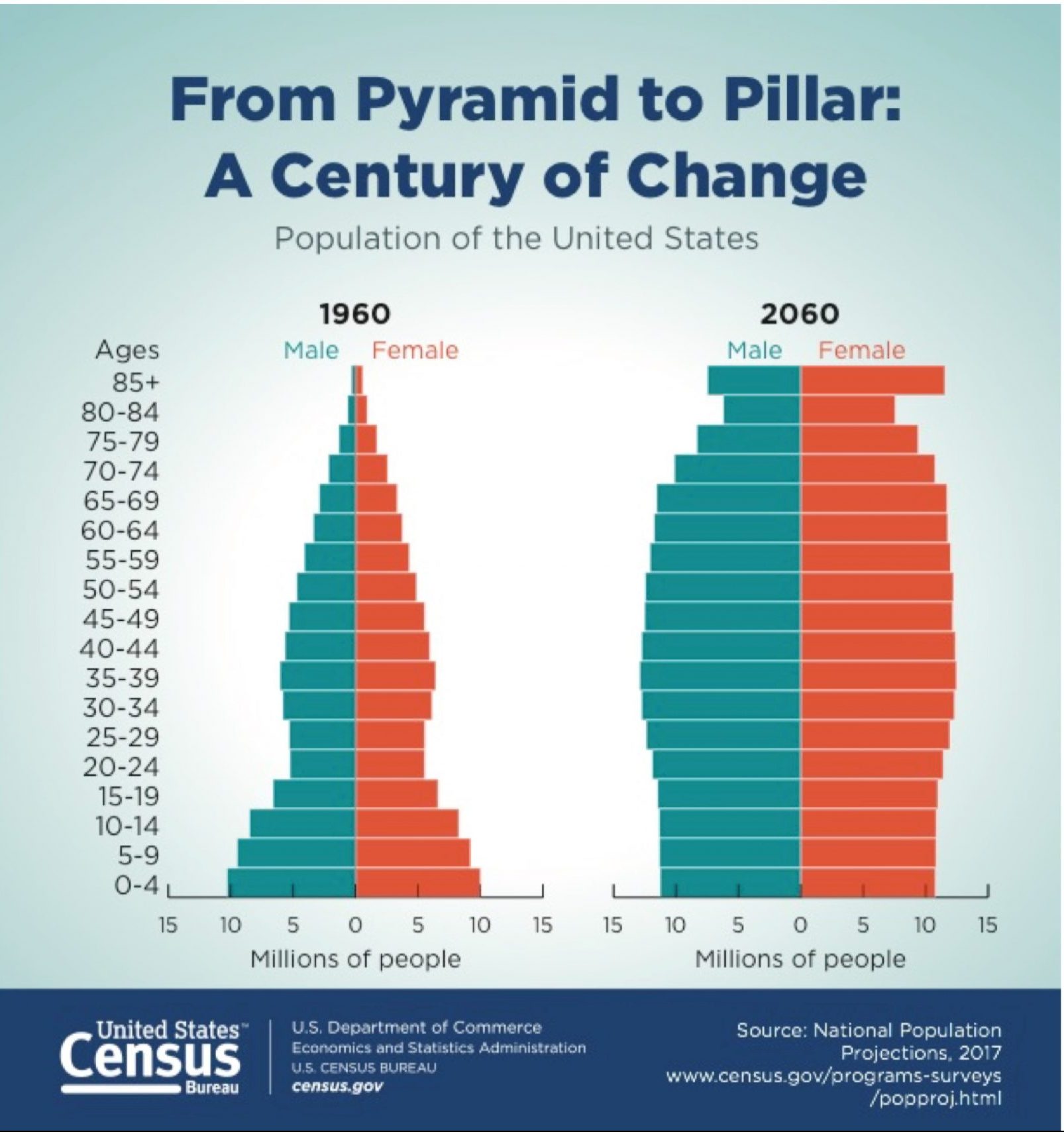

The world is aging and changing. Graph 1, published by the U.S. Census Bureau, shows how the population of the United States is shifting. In 1960, we had a population pyramid, with a large number of younger people tapering up to a very small number of older people. In 2060, by contrast, it’s projected that we will see relatively equal numbers of people across the age span.

Graph 1

This is a massive demographic shift, which requires a new way of thinking about what the workplace looks like. It is not going to be a race to see who can attract the most young people. We have to learn how to accommodate older people, and not just accommodate older workers, but think about what kinds of opportunities this shift could provide for us.

Unfortunately, many of our current policies and practices are tailored to that 1960 pyramid. The government defines the prime working age as between the ages of 25 and 54. Normal retirement age is considered to be 62 or 65. For the most part, we look at education and higher education as being front-loaded, rather than upskilling across the lifespan. All those things are going to have to change.

We know that people are staying in the workforce longer. Before COVID-19, approximately 20-25 percent of people aged 65 and over—and 250,000 people aged 85 and over—were in the workplace. Every survey that has looked at the question has found that significant percentages of Americans intend to work beyond what has been considered typical retirement age.

Yet many of our policies do not accommodate those realities. So, I would encourage everyone to ask:

- What are the opportunities for all of us, knowing that people are living longer, and that many people want to and can continue to work?

- What can we do with that built-up expertise and insight that older adults have, and how can we use that to benefit our workforce?

The biggest barrier to reaping these benefits is ageism. Ageism is prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination against people based on age. It can be directed against younger people as well as older. But we know that when directed at older people, ageism has incredibly harmful effects, not only for older people, but also on our communities and the economy.

This prejudice can be as simple as saying, “I really don’t like having old people around,” or Mark Zuckerberg’s “Younger people are just smarter.”

Stereotyping is making assumptions about what people can and can’t do: “Those older people, I just don’t think their skills are up to date, and they’re not what we need right now.” And the common assumption that older people are digitally incompetent persists, despite all the mounting evidence to the contrary.

Discrimination can take place at all stages in the workplace. It can take place in recruitment and hiring, when we use online advertising to target only people of younger ages. It can look like a job description that calls for “digital natives,” or that says we only want people who have less than three years of experience. Once someone is on the job, it can take the form of denying people the opportunity to participate in new training initiatives, or actually pushing someone out.

A study by the Urban Institute that was released at the end of 2018 showed that 56 percent of people who entered their 50s in the United States with stable employment were pushed out or laid off, and only 10 percent of them ever recouped financially. Older women and people of color, if they are laid off, tend to experience much longer periods of unemployment before they’re able to return to the workforce.

At the same time, the Economist Intelligence Unit in conjunction with AARP did a study that found that the cost to the U.S. economy in 2018 of age discrimination in the workplace was $850 billion in lost productivity, and of that, $44 billion was the cost specifically to the tech sector. Looking forward to 2050, the projection is that the tech and automotive sectors have the most to lose, and on the other hand, potentially the most to gain, if there are active efforts to recruit and retain older people in our workplaces.

Ageism: Underlying Beliefs

So why is this discrimination going on? Frameworks Institute did a study on how people think about aging and ageism in America. They found that a lot of the ageism that we see is a result of deeply embedded cultural models or patterns of thinking that we have about aging itself, and about older people.

The first cultural model is the conflict between an idealized view of aging and the perceived reality. The idealized view is what I call the “pharmaceutical ad version,” where we’re on the beach holding a glass of champagne; it’s a time of self-sufficiency and leisure. The perceived reality of aging, on the other hand, is basically the idea that it’s a time of decline, loneliness, and dependence; it’s all about loss. This widely-held view totally ignores what experts know, which is that as we age, there is an enormous opportunity for contribution to our communities, our workplaces, and our economy.

The second cultural model is called “us versus them.” In this case, we see older people as pitted against younger people in the workforce, and more broadly in the community, in a competition for resources. This sounds like, “If older people stay in the workplace, they’re taking jobs away from younger people.” This belief ignores all the economic studies that show that the reverse is true: the longer people stay in the workforce, the better for everyone on a macro level, in terms of overall economic growth.

Individualism is a very strong theme, certainly, in America. It’s the idea that if someone isn’t doing well as they get older, it’s their fault. They didn’t make the right choices. In the workplace, it sounds like, “If Judy had just kept up with her skills…” In reality, studies have shown that older workers are much less likely to receive opportunities for ongoing training and upskilling than younger workers.

The final cultural model is this idea of nostalgia. In the good old days, the economy was stable, we had pensions and social security was solvent. The challenge of this particular line of thinking is this: If we’re thinking about the good old days, we’re not able to think innovatively about the opportunities presented by an aging demographic. What would be the opportunities if we had people with a lot of experience and expertise who could work on some of our problems?

Strategies to Reduce Ageism

The good news is that there are effective strategies that we can deploy to not only reduce ageism overall, but also to address workplace age discrimination.

Research from the Global Campaign to Combat Ageism and other sources points the way to effective strategies to reduce ageism. These include:

- Fostering intergenerational connection. This can take place in K-12 and higher education, and it can certainly happen in the workplace. In the same way that exposure to any group that is different from the group that you identify with creates increased awareness and understanding, fostering intergenerational connection is very effective in reducing ageism.

- Educating people about ageism and implicit bias. In the workplace, we can train hiring managers, supervisors, and others on implicit bias, i.e., bias that we have and may not be aware of. Research shows that when managers are trained in implicit bias and are shown how to recognize it, this can help to stop bias in its tracks. This training must be embedded; it can’t be simply a one-off workshop but must be reinforced over time.

- Reframing our image of the older worker. Part of what we need to work on, instead of just relying on myths and stereotypes, is looking at the reality of aging, and viewing the older worker as a valuable source of insight, experience, connections, and resilience. Research shows that older workers are very motivated to learn, though we may learn in different ways. We are also very motivated to exceed expectations, and have higher degrees of engagement in the workplace, which can lead to productivity gains. On average, older workers have better communication skills and other soft skills. We know that older workers tend to be very loyal, and on average have four times the tenure of younger workers. We also know that as we get older, our “crystallized intelligence”—knowledge that comes from past experience and learning—grows, which can be an incredible asset to workplaces.

- Advancing age-inclusive policies and laws. There are specific policy solutions that can help address workplace age discrimination. One is strengthening age discrimination laws, on a federal and state level, so that they are on a par with other forms of workplace discrimination laws. We can let our elected representatives know that we support proposed legislation to add an Older Workers Bureau within the U.S. Department of Labor. We can champion legislation like what New York and Connecticut did to remove graduation dates and other age-identifiers from job applications. Currently, it is illegal to ask job applicants their age, but not their high school graduation dates, which for most of us are a proximate for our age. And within our own communities and states, we can ensure that policies supporting talent pipeline development and use of workforce development funds include people of all ages, not just younger people.

But the idea here is not to just hire older workers instead of younger ones. The real benefit comes when we have intergenerational teams. We know that when we have age diversities, similar to when we have teams that are racially, ethnically, and gender diverse, then we have improved team problem-solving and improved creativity. And we know that intergenerational teams increase both productivity, and over time, profitability as well.

What can you do in your workplaces and in your communities?

There are some very specific and concrete actions you can take to reduce the impacts of ageism in your workplaces and in your communities. First, include age in diversity, equity, and inclusion policies. This pushes people to consider what equity for people of all ages would actually look like in the context of your company, and we all know “what gets measured, gets done.” This does not have to be a stand-alone effort: Many of the actions you may take to encourage DEI overall also apply to age.

Use age-friendly language and images in recruitment materials. If all the images are of younger people, or if you are asking for high school graduation dates or saying, “We want less than X years of experience,” those are a code telling older people, “We really don’t want you to apply.” There has also been a lot of discussion recently about bias that is built into algorithms, and this is really important to look at if you’re using algorithm-based application screening mechanisms. Finally, to refute the myth that older people don’t have current skills, use skill-based assessments.

There are other actions that can be taken to reduce the impact of ageism in the workplace itself. One of the best examples of this approach is BMW in Germany. BMW was faced with the question of what would happen if a large number of people retired at the same time. For a relatively modest sum of money, they basically went around and asked people, “What would it take to keep you here?” And some of the things turned out to be really simple: instead of standing all day, maybe we could have high stools and flexibility in our work hours. Interestingly, out of the various workplace adaptations that were attractive to older people, some of them were specific to getting older, and some of them were the kinds of things that make a business attractive to anyone at any age.

Investing in training and upskilling across the talent pipeline is another way to reduce the impact of ageism. Instead of making the assumption that new arrivals get trained and people who are deemed promising get trained and move up in the company, ensure that at every point across talent pipelines, training opportunities are available. Research has demonstrated that older adults value and prize ongoing learning opportunities.

Deliberately encourage reciprocal mentorship. A study released by AARP showed that 70 percent of younger people actually wanted mentorship and considered it valuable, and older people also had a desire to mentor. But, we want to take that one step further and realize that any organization can benefit when they encourage people to learn from each other.

Going beyond what happens in the workplace, we also need to think about the whole ecosystem, and look at policy. It is very important to foster education and training across the lifespan. Institutions of higher education have a strategic business imperative to consider older students as part of their target audience. In the United States, workforce development programs have historically been seen as being for younger people. There is now a push to encourage workforce development programs to look at older workers. We can begin to collect data on people in the workforce aged 65 and over. Too often, data is missing about this population, which allows policymakers to make decisions based on stereotypical assumptions that older people don’t want to work or are not interested in ongoing upskilling. These are all opportunities for advocacy within your communities.

So, it’s not just within your organization, but pushing the ecosystem around you as well to upskill older people. Ultimately, the change we’re trying to drive is this big idea that we can start looking at older people in multi-generational workplaces as a source of innovation that can drive our organizations forward, especially in times of great flexibility and uncertainty.

Janine Vanderburg leads Changing the Narrative, the leading effort in the U.S. to change the way people think, talk and act about aging and ageism through evidence-based strategies, strategic communications, and innovative public campaigns. She chairs The Encore Network and serves on the board of the Center for Workforce Inclusion Labs.