By Tyler Norris

Education is critical to our well-being. It opens doors to opportunity for social mobility, higher income and employment security, all of which have an impact on health status. In fact, national studies have found that people with more education tend to report being in better health, compared to people with less education.

Education’s impact on well-being not only adds to personal fulfillment, it helps to extend life expectancy and even makes the next generation healthier. On average, college graduates live at least five years longer than people who do not complete high school.

In other words, more education leads to improved intergenerational health. Yet, not everyone has the same access to educational opportunity. Educational attainment in the U.S. varies considerably across demographics. Among White adults over age 25, more than 37 percent have college degrees, compared to 23 percent of Black adults and 16.4 percent of Hispanic adults. This undercuts well-being for all in our nation.

These disparities stem from a history of discriminatory practices in institutions such as schools and housing that continue to disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities. The legacies of those practices include:

- Separation of Black and White Americans in the 20th century impacted where people lived, worked and went to school. Today, this legacy lives on through the disproportionately high number of students of color attending under-funded schools in low-income communities.

- Achievement gaps. Inequitable funding across school districts contributes to students of color in low-income communities attending schools with limited resources. Barriers families face, such as income and housing inequality, contribute to gaps in learning as well. Of the two-thirds of U.S. children who are not proficient readers by the end of third grade, 80 percent come from low-income families.

- Higher rates of discipline. Three million students — disproportionately boys of color and students with disabilities — are punished with out-of-school suspensions each year. Black students made up 15 percent of students in public schools in the 2015-2016 school year, but accounted for 31 percent of arrests on school grounds.

The obstacles many students face are systemic and embedded across the education system, from preschool through higher education. From access to quality early learning to disability accommodations to financial aid, students from low-income communities and communities of color are the most likely to get short shrift.

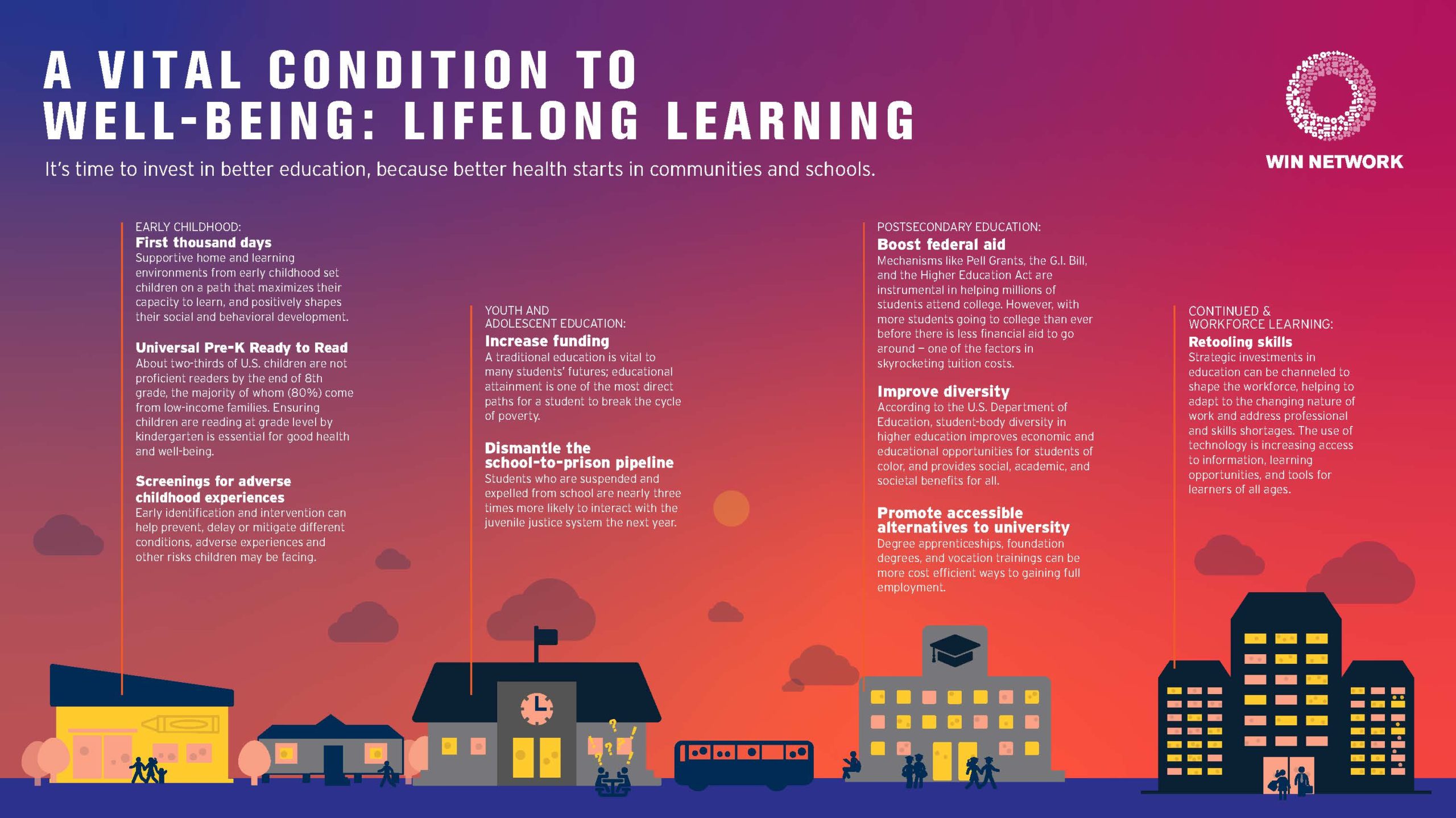

America’s education system is in desperate need of reform, and there’s a lot we can do right now. Here are some steps we need to take to dismantle barriers and ensure every student has access to quality education and, as a result, the best chance at a long and healthy life.

Increase education funding.

Every school needs funding to run properly. On average, federal funding accounts for about 8 percent of schools’ budgets, with the rest coming from state and local sources. But state funding for education took a hit across the country following the 2008 recession, and many states are still struggling to restore those budgets more than a decade later. Underinvestment in education has led to larger class sizes, underpaid teachers, and a lower quality learning experience for students.

We have to invest more in schools because access to education is vital to many students’ futures; educational attainment is one of the most direct paths for a student to break the cycle of poverty. One , looking at low-income students found that a 10 percent increase in funding per student over the course of their 12 years in public education resulted in a 10 percent increase in graduation rates and a 6 percent decrease in adult poverty rates. With that in mind, we need more equitable approaches to funding that will better support communities where local taxes are insufficient.

In New Jersey, for example, the 2008 School Funding Reform Act implemented a weighted budgeting approach to ensure every school district would receive enough funding based on the specific needs of its student body. Once the budgets for every school district were formulated and contributions from local taxes were accounted for, the state would pay the difference to ensure every district met state standards. Though this budgeting approach was not enforced under former Governor Chris Christie’s administration, Governor Phil Murphy has since signed laws to further improve the formula and passed a budget that will increase aid for 370 New Jersey school districts.

Address health equity — in schools.

Because students spend much of their time at school during the academic year, and because health concerns can lead to chronic absenteeism or difficulty learning, schools are an ideal place to provide health care to children and their families.

In Greenville County, South Carolina, a number of schools are participating in a district-wide initiative to do exactly that by bringing healthy lunch programs and health centers into schools. School-based health centers, which integrate resources like mental health professionals and nurses into schools, make students less likely to miss school and increase access to health care that may otherwise be hard to reach. So far, the district has seen 97 percent of students able to return to class after visiting the health center.

Dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline.

The school-to-prison pipeline, a trend where students are systematically pushed from the public school system into the criminal justice system, is driven by strict policies that criminalize even minor acts that break school rules. Students who are suspended and expelled from school are nearly three times more likely to interact with the juvenile justice system the next year.

More schools are replacing traditional disciplinary actions, like suspension and police referrals, with approaches centered around restorative justice. This approach uses dialogue to address the root cause of behaviors and aims to repair relationships among students and staff. At one high school in Oakland, California, putting restorative justice in place reduced suspensions by half — which meant students could stay in school to learn and thrive.

By giving students and staff the skills to discuss conflict and establishing spaces where disputes can be resolved, schools can keep students engaged in school, rather than distancing them from the education system. Studies show a focus on reconciliation rather than punishment improves academic outcomes and decreases instances of violence overall.

When every young person has access to a quality education and supportive school environment, we will see widespread positive social and behavioral development, an increasing number of pathways for students to achieve their full potential, and more students ending the cycle of poverty in their families and communities.

It’s time to invest in better education, because better health starts in schools.

Tyler Norris is CEO of Well Being Trust. From 1990-1995, he led Civic Assistance at the National Civic League.