By Laurel Blatchford and Tyler Norris

Everyone needs a stable, safe place to call home. Where we live has a significant impact on our physical and mental health, as well as our access to well-paying, stable jobs and community resources like parks and stores.

In fact, housing can promote good health and enhance well-being when it is within reach of public transportation, healthy foods, medical care, schools and other vital destinations. Healthy homes must also be free from hazards that can make us ill, hamper child development or even kill us, such as carbon monoxide, allergens and lead. With the right systems change, everyone can have a happy home that promotes their well-being.

Unfortunately, though humane and healthy housing is a basic necessity, it comes at a high cost and continues to be inaccessible to many.

And, in communities of color specifically, a long history of racism and disinvestment has limited people’s ability to access housing that promotes health and left many living in neighborhoods isolated from opportunity and in low-quality homes. These legacies include:

- Urban decline. After World War II and the Great Migration, many White and middle-class families moved to suburbs. And, the concurrent disinvestment in urban areas led to fewer well-paid jobs and opportunities and less funding for schools, social services, infrastructure and public safety—this also created the conditions for today’s gentrification crisis, where low-income communities are now being displaced to make way for rising urbanization.

- Housing discrimination. Redlining — refusing loans to people because of the racial demographics where they live — once prevented many Black families from owning homes and building wealth. Although the practice was banned by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, its impact persists systemically.

These historical intentional housing inequities have led to lasting health disparities that are still experienced today. For example, researchers blame about 40 percent of childhood asthma on exposure to toxins in the home — and Black children have asthma at nearly twice the rate of White children.

Affordability is deeply intertwined with healthy housing. A survey from Enterprise Community Partners’ Health Begins with Home initiative found that more than half of the 1,000 adult renters who responded had delayed some form of health care due to high costs. Those who were severely cost-burdened—paying more than half their income in housing costs—were much more likely to forgo health care than their peers. As the evidence mounts, the interdependence between health and housing cannot be ignored.

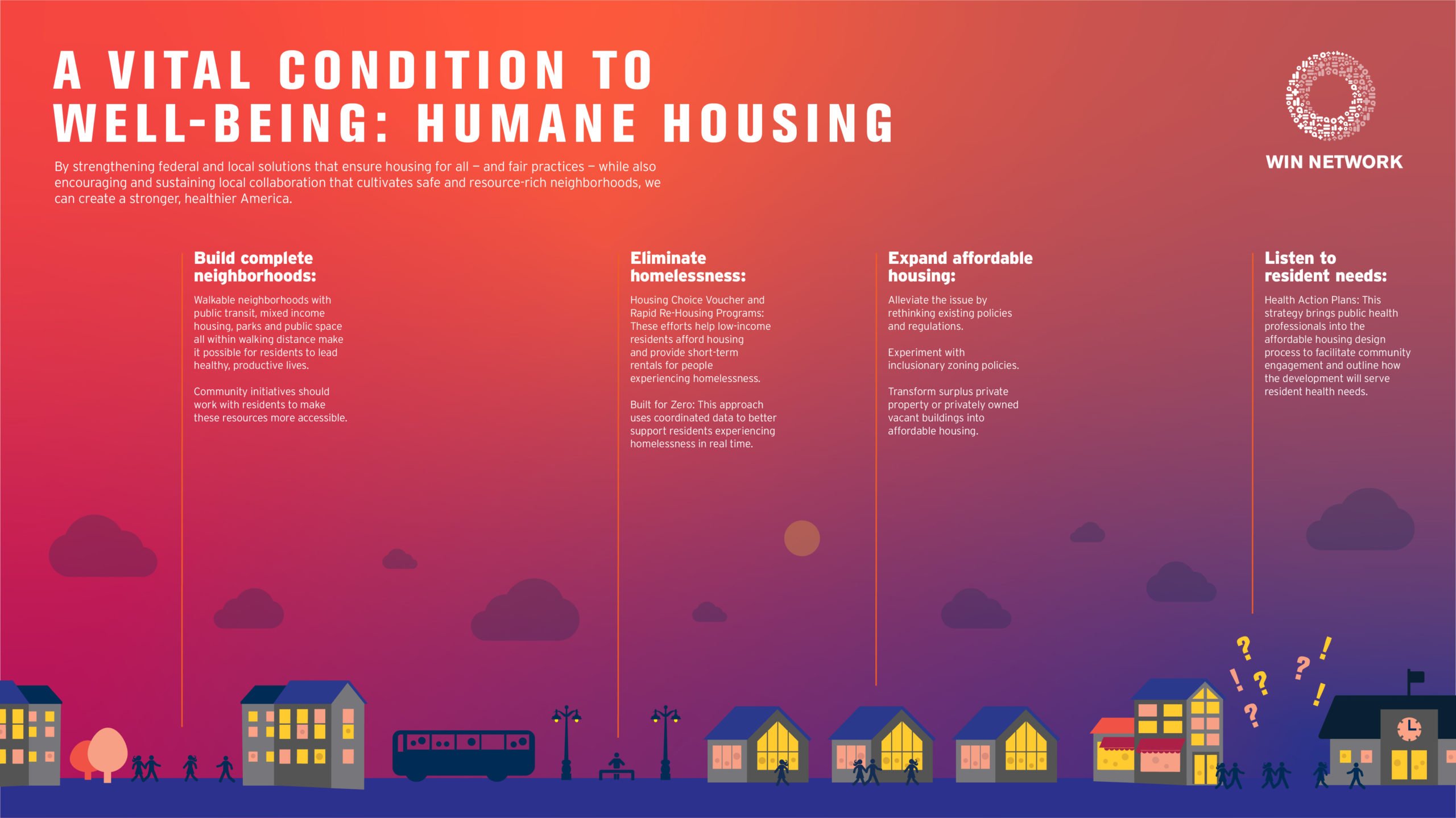

While housing issues are deeply engrained in American society, many communities are addressing these issues, leading the way with a collaborative approach, and improving health outcomes through humane housing. Their solutions include:

Build complete neighborhoods

Walkable neighborhoods — complete with public transit, mixed income housing, parks and public space all within walking distance — are making it possible for residents to lead healthy, productive lives. People living in these neighborhoods are more likely to trust their neighbors, participate in community projects, and volunteer than those living in sprawling, inaccessible neighborhoods.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina displaced 400,000 people in the city of New Orleans alone, with devastating consequences for the lowest-income and most vulnerable families. Countless properties were damaged beyond repair, including four public housing complexes that housed thousands of families. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Housing Authority of New Orleans took this opportunity to start anew, using disaster recovery funding to completely redevelop the properties. Enterprise and Providence Community Housing were tapped to transform the Lafitte public housing complex into a low-density, mixed-income, walkable community called Faubourg Lafitte.

To date, the project has transformed 78 dilapidated public housing buildings into more than 500 new homes for community members and former Lafitte residents. The redevelopment process also created the Sojourner Truth Neighborhood Center, which offers services and classes for residents and the community at large. Beyond housing, the Faubourg Lafitte community is accessible by public transit and includes neighborhood amenities like a playground, a field, a fitness center, tennis courts, office space, and more. The redevelopment process intentionally created a safer, more resilient, affordable and healthy place for New Orleans residents to call home.

Complete neighborhoods don’t have to be built from scratch. In Houston, Texas, the Complete Communities initiative works with residents and leaders to improve existing neighborhoods and ensure more resources — such as transit, green space, schools, grocery stores and shops — are within reach for residents, while also remaining affordable.

So far, the city has identified 10 neighborhoods and is now engaging with residents through public meetings and small group outreach. The goal is to understand residents’ vision for their neighborhoods and create plans to bring their ideas to life. By focusing community improvements around the needs of the people living there, cities can more effectively fill the gaps in neighborhood resources.

Expand affordable housing

As urban living rises in popularity and the cost of housing soars in many parts of the country, setting aside land for affordable housing is becoming increasingly important. Properly managed, affordable housing has been found to improve mental health and physical safety and reduce health risks often found when building conditions—such as lead, asbestos and other chemicals and molds—are not well regulated.

Though there is no silver bullet for the affordable housing crisis, leaders can find innovative ways to alleviate the issue by rethinking existing policies and regulations. In St. Paul, Minnesota, the mayor approved a tax break to encourage property owners to set aside a fifth of their housing units for low-income residents. Now, the city has 770 apartments in its affordable housing program, up from 200 last year.

Many cities have experimented with inclusionary zoning policies, which similarly require developers to designate as affordable a portion of any new housing units created. Developers seeking to build only market-rate units also have the option to contribute to a fund that directly supports affordable housing development. In addition to providing more affordability without requiring additional subsidies from the government, these policies can also combat racial and socioeconomic segregation by creating mixed-income communities where residents of all income levels can belong.

Other strategies that have been implemented on the local level include transforming surplus public property or privately-owned vacant buildings into affordable homes, establishing local housing trust funds to create a dedicated source of funding for affordable housing, providing services to smaller landlords to preserve naturally occurring affordable housing, passing legislation that streamlines the development process and much more.

Every municipality has unique needs; the affordable housing strategies that work best in Boston might not be the same as the most effective policies in Omaha. Local leaders must mix, match and customize to design policies and programs that will best support affordable housing development in their communities.

Eliminate homelessness

Homelessness has been on a general decline in the U.S. over the last decade, thanks to federal, state and local efforts implementing evidence-based practices that get people quickly into housing and support them afterward.

But the rising cost of housing has hampered progress, and in many cities across the nation the number of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness has grown in recent years. Homelessness’ underlying causes — such as housing affordability, discrimination, and physical and mental health — still need to be addressed. Policies like the Housing Choice Voucher program, which helps low-income residents afford housing, and rapid re-housing programs, which provide short-term rental assistance and services to people experiencing homelessness, are vital for lifting individuals and families out of homelessness.

In Denver, Colorado, counties are joining the nationwide Built for Zero initiative to end homelessness. The initiative — which helped Abilene, Texas, reach its goal of ending veteran homelessness earlier this year — coordinates data across counties to better support residents experiencing homelessness in real time.

Listen to resident needs

Best practices in housing and health are increasingly recognizing how essential it is to not just design programs and policies with people’s needs in mind, but to actively involve them in the process. Without input from the community they hope to impact, practitioners are simply guessing at what might work best.

One powerful example: when Chicago-based community-development corporation LUCHA began renovating one of its affordable housing communities, several residents asked if the new units would have carpeted floors. Many did, and it turned out that most residents did not own vacuum cleaners, which made the floors dangerous for asthmatic children. Resident participation in the development process could have informed this basic design choice and created a healthier environment for everyone.

Far too often, feedback from impacted communities comes far too late in the process of developing a housing community or health program to effect substantive change. Enterprise and partners have begun working with developers like LUCHA to create Health Action Plans, which bring public health professionals into the affordable housing design process to facilitate community engagement and outline how the development will serve residents’ health needs.

Humane housing should be a top priority for all U.S. cities. By strengthening federal and local solutions that ensure housing for all—and fair practices—while also encouraging and sustaining local collaboration that cultivates safe and resource-rich neighborhoods, we can create a stronger, healthier America.

Tyler Norris is CEO of Well Being Trust. From 1990-1995, he led Civic Assistance at the National Civic League. Laurel Blatchford is president of Enterprise Community Partners.