By Albert Dzur

In his teachings and writings, John McKnight, co-founder and co-director of the Asset-Based Community Development Institute at DePaul University, has echoed Alexis de Tocqueville’s appreciation of the value of healthy civic associations. As coauthor of Building Communities from the Inside Out and author of the Careless Society, he has also expressed skepticism when it comes to the role of formal government agencies and professionalized social services in care-giving and community development efforts. Much of his work has focused on the under-appreciated “assets” provided by ordinary citizens, neighborhoods and informal associations.

“Many people think democracy depends on an informed electorate,” he noted in a recent conversation with National Civic Review contributing editor Albert Dzur. “To be informed they should deliberate together—the mode exemplified by the New England town meeting. I think that kind of associational activity is important but relatively rare. I don’t think Tocqueville was thinking about associations that were deliberative, and I don’t think there were very many of them.” Most associative life, McKnight suggested, is built around groups of people who come together because they have an affinity. Their focus is less often on “what to do” than “how to do it.”

A Conversation with John McKnight and Albert Dzur

Dzur, a distinguished research professor at Bowling Green State University, began their conversation with a question about the relationship between governmental institutions and noninstitutional associations.

John McKnight: I’ve written a paper, called “Re-functioning,” and it describes how functions that are now performed by institutions have grown and grown resulting in the loss of functions from the associational sphere.1 So, questions about relationships (How shall citizens relate to government?) are, for me, not the most important questions. Instead, let’s get a map of functions and ask, “Whose responsibility is it to perform what functions?” Then we can ask the relational question. But the first question is, “Whose responsibility is it to do this or that function?”

I was just talking with a man from Holland. Up until a few years ago, he said, in our cities at 7:00 to 8:00 every morning a householder would come out with a broom and a bucket and a mop. And they would clean the sidewalks and street in front of their house. We never had street cleaners until recently. And, who runs the street cleaners? The city.

This seemed to me to be a particularly vivid example of the transfer of function. Something that each household thought was a part of their daily life had become transformed. This moved them from producer to consumer and they are arguing with the city about how often the street sweeper should come by.

That’s a very simple example of the problem of framing this question. Is the question, “How can citizens relate more effectively to government, as government cleans its streets?” Which is the way it will always be framed now: “How can you participate in helping schedule the street sweepers?” or “How much money do you want to put into street sweepers?” As against the functional question, which is “Who ought to be cleaning the streets?”

Albert Dzur: Public administrators often say, “We are interested in citizen engagement! We’ve advertised this public forum, we have it scheduled after work, we even have snacks, but no one shows up!”

McKnight: Yes. Absolutely!

Dzur: And you’re not sympathetic to their plight, are you?

McKnight: No. I’ve written another paper on what I call “precipitation.”2 This is the idea that people in government—especially city managers, mayors, top bureaucrats—can engage in a process that stimulates citizen associational action but has no boundary in terms of what the action would be. The most commonly recognized example is mini-grants.

Most mini-grants come substance free. They say, “What do you want to do?” and “How can we help you?” They are a precise example of something that is citizen generated to be productive and that is precipitated by government. I am increasingly interested in getting public officials to think much more as precipitants, rather than “co-somethings” I’m all for “co”–“co-production,” “collaboration,” all of those terms. But some of the most significant changes I have seen have come about because of government precipitating citizens’ action.

I do a webinar with Peter Block under the title, “An Abundant Community,” and we recently did one with Mike Butler, who is the police chief of Longmont, Colorado. He doesn’t think like any police officer you’ve ever met. He thinks about security first. He asks, what are the elements of security, and how do I support those elements? And then, over here, I have this element called “police,” who are the last resort, because they’re probably going to be the least effective.

The Abundant Community with Mike Butler

Broadcasting live with Peter Block, John McKnight, and special guest Mike Butler.

Posted by The Abundant Community on Tuesday, August 6, 2019

Dzur: I’ve noticed that you talk about community policing as an example of power sharing between professionals and citizens.3 It works sometimes. But it is hard for police to just be that corner piece, and sometimes community policing becomes public relations. When it works, it seems to require a kind of humility on the part of police officers: the admission that they can’t do it all themselves. You write in a similar way about schools, that there’s a kind of humility in the best schools: “We can’t do education on our own, there’s absolutely no way.” It’s difficult, however, for professionals to balance a sense of humility with a sense of public responsibility.

McKnight: Humility, yes. I think that’s right. It recognizes that I’m not the center of the world.

Dzur: Yes, absolutely.

McKnight: “What is the context in which I am operating?” is the real question for the professional. Let me go back to police. You raised a question about public relations and community policing.

Dzur: Right, that community policing can often devolve into public relations precisely because the police hang on to this idea that they’re the central actors.

McKnight: A lot of police, when this started, saw this as a way of getting local people to be the eyes and ears for the police. And that means you’re a voluntary adjunct to our system. And that’s also what most community outreach is to human resource organizations.

Dzur: People get fed up with being used in that way.

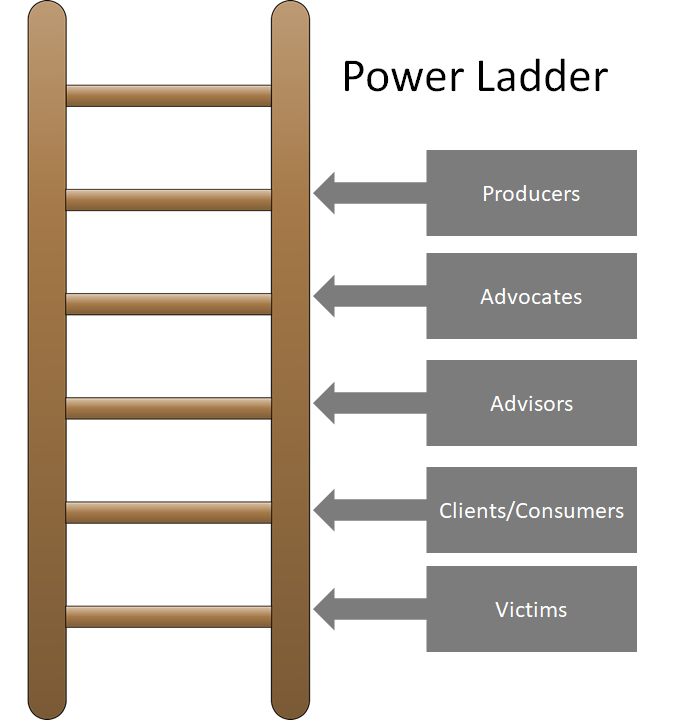

McKnight: Yes. In the ABCD materials you’ll see what’s called a “power ladder,” with five steps. If I were an administrator, and I wanted to know where I was in terms of citizen enablement, I’d look at this ladder.  On the bottom level is a community where people believe they are victims. The next step up is, “We are clients and consumers.” Because we are victims, institutions can help us, and we’ll become their clients and consumers. The next step up is to become advisors. A hospital has a “citizen advisory committee” or a city council has an “advisory committee.” The next step up is advocacy. Being an advisor means that the institution can or cannot take our advice. In advocacy, citizens have power beyond advice. That power may itself be the factor that makes your voice heard. But the implementation is still done by the institution. The top of the ladder is “producer.” I am the producer of the future. I have the power, together with other citizens to decide what is to be done, how it shall be done, and who shall do it.

On the bottom level is a community where people believe they are victims. The next step up is, “We are clients and consumers.” Because we are victims, institutions can help us, and we’ll become their clients and consumers. The next step up is to become advisors. A hospital has a “citizen advisory committee” or a city council has an “advisory committee.” The next step up is advocacy. Being an advisor means that the institution can or cannot take our advice. In advocacy, citizens have power beyond advice. That power may itself be the factor that makes your voice heard. But the implementation is still done by the institution. The top of the ladder is “producer.” I am the producer of the future. I have the power, together with other citizens to decide what is to be done, how it shall be done, and who shall do it.

Dzur: You’ve been enormously critical of professionalized institutions, which you characterize in a zero-sum way.4 The more productive work an institution does, or claims to do, the less there is for citizens to do. But the claim is part of your argument. Healthcare institutions claim to produce healthcare, but they don’t. Educational institutions claim to produce education, but they don’t. Criminal justice institutions claim to produce security, but they don’t.

McKnight: Right. That’s true.

Dzur: How do you break into those spheres of social organization and create the power ladders you are talking about, where you have an institutional attitude of humility—just to use that word again—that admits, “We cannot produce healthcare or education or security by ourselves, we can’t even come close.” How can people on the inside of institutions recognize that they have to build a better power ladder or—to use a related concept—to genuinely “co-produce” healthcare, security, education?

McKnight: I am much more focused on associational life than on institutions that want to know how to relate to these associations. So I am not a very sophisticated thinker about your question. However, you put it well in your written question; you said, “All these professionals are going to work, and they intend to do something helpful and something useful.” So, I tried to think about what might they do.

Dzur: Yes, I was thinking, on one hand, about how you are acerbically critical of professionalized institutions. Yet, at the same time, you do meet with people like Chief Butler, who sees the police as a corner piece. And even when you are being critical, I don’t think that you’ve completely given up hope that these institutional worlds—of police departments, schools, hospitals—can change.

McKnight: Among the professions, the one I’ve dealt with most often over the years is in the “developmental disabilities” field. They don’t have many large institutions left. They now have mostly smaller systems—group homes, independent living centers, that kind of thing. The turnover rate for new employees is a third of them leave every year.

Now, why do people go into that field? If you ask the people who’ve been around it for a while, they’ll all agree, “We draw from the community people who want to care.” And what happens is that within a year, a third of these people discover that they’re in the wrong place. They want to care, but they are in a structure that so violates their sense of what they would do if they wanted to care that they leave.

If I were talking with a group of professionals, the real institutional questions might be, “How can you reduce the turnover in people who want to care? How can they be fulfilled so that you were a support unit for their care?” I would like to have more people in those systems who genuinely care, who can manifest their care.

To a professional in any field, I would say: never leave any client without knowing two things about them personally. Number one, what is the real context they come from? And number two, what gifts, talents, and abilities do they have? You won’t know those two essentials unless you’re a listener rather than a prescriber.

So those two things I think would guide them into a different relationship and conceptual understanding: “I am here with this person who comes from a neighborhood where a lot of people still take care of one another. How can I not get in the way?”

In Devon, England they have an initiative going in which doctors do what they call social prescribing. The doctor is recognizing the context the person is in and actually writes a prescription that might say, “Because you have a dog and there are three associations of dog lovers in your community, I prescribe that you get to know about them and become involved with at least one.”

Social prescribing is a recognition of context. Gifts and assets are a way of understanding what capacities people have to be actors in their own health. And you don’t get either of those if you don’t listen.

In Illinois, the most common thing that gets you up before a medical ethics board is you’ve become “involved with the client.” But that’s what I’m talking about! Becoming involved with a client! And it’s seen as “anti-professional.” Although, I do know professionals who operate in this manner. Robert Mendelsohn was a great doctor, who lived in my neighborhood. He was the first medical director of Head Start and a total heretic. The first thing he would do when patients came in was to say, “Well tell me about this.” He would get their version of what’s wrong. And the second question would be, “What would your grandmother say you should do about that?” That’s his opening. I respect what you think is wrong and I respect the community from which you come—I respect their judgment about what to do about it.

Dzur: It’s interesting because in my experience, some of the best trained and most intelligent professionals are clever enough to know they have their limits. And so, they listen.

McKnight: They may not always be humble but they’re not arrogant.

Dzur: To conclude our conversation, I’m curious about your optimistic spirit. You’re tough-minded and realistic and you see all the bad things that other people see, but it strikes me that you’ve got a very positive view of American democracy and I wonder what you hold your hopes on these days.

McKnight: I am an optimistic person. It’s hard to be hopeful these days, but I think I am just that way. How’d I get that way, I’m not sure.

Dzur: Are there things in the world that confirm that optimism from time to time?

McKnight: I have a particular set of experiences. My first job was as a neighborhood organizer in Chicago. Saul Alinsky was the godfather of neighborhood organizing at that time and when I got out of university I started work under his umbrella. I spent a long time out in neighborhoods. He’d get the neighborhood organization to set aside a fund to pay an organizer before he’d send an organizer in. They had to have like $20,000 in the bank before he’d send an organizer in. The first thing we had to do was what he called “one-on-ones;” they still call them this. We’d spend an hour in discussion with people in the neighborhood. Not just the leaders—the aldermen and the ministers—but the rest of the people. And we would spend 3 to 6 months doing 6 one-on-ones a day before anything else happened.

From Alinsky’s point of view, and he was probably right, we knew more about the popular will and mind of that community than any people who were called “leaders.” I think very few people have that experience, in depth, except people who carry on this trade.

When you do that, you can’t help but be optimistic. It told me who we are. I’m not saying people are good, but in fact I’ve never met people I’ve thought were really bad. And I think that experience probably accounts for my standpoint. I’m always referencing anything anybody tells me with what I learned there—what I know about the nature of people, particularly if you will approach them as though they are the authority.

You use the word “humility.” If you were an authority in a city government who had humility, you’d treat a neighbor as though they had the authority.

Dzur: Or at least the capability of sweeping off their own stoop.

McKnight: Right. It’s not a theoretical thing with me. I spent years knowing what the 32 householders on that block believe in, are committed to, and, because I was an Alinskyite, what they’re angry about.

1 McKnight, John. 2019a. “Re‐functioning: A New Community Development Strategy for the Future.” Unpublished manuscript on file with author.

2 McKnight, John. 2019b. “A Guide to Government Empowerment of Local Citizens and Their Associations.” Unpublished manuscript on file with author.

3 McKnight, John. 2017. “The Educating Neighborhood: How Villages Raise their Children.” Connections: An Annual Journal of the Kettering Foundation: 15-22.

4 McKnight, John. 2013. “The Four-Legged Stool.” Dayton: Kettering Foundation Press.