Jon Abercrombie, who passed away last month, was an influential civic innovator who helped make Decatur, Georgia, a sterling example of participatory and deliberative democracy.

After an already-accomplished career in youth ministry and as a developer of affordable housing, Abercrombie was confronted in the 1990s with a number of painful tensions in Decatur. The community was troubled by disputes over planning and zoning, racial tensions, and homophobia. One of the more dramatic incidents was a fistfight during election campaigning between a member of the city council and the husband of the president of the local college.

In an effort to address these tensions and long-term planning questions, Abercrombie began to organize the Decatur Round Tables, a process that engaged hundreds of residents in small-group deliberations on the future of the city. He worked with visionary city manager Peggy Merriss, mayor Elizabeth Wilson, councilmember Jim Baskett, and a number of other local leaders to recruit participants, facilitate the sessions, and assemble the ideas into a plan for Decatur. The Round Tables helped the city chart the course of its development, deal with contentious issues, and become a more tightknit community

Abercrombie (second from left) working with Round Table facilitators in 1998

Decatur became a national model for participatory planning, organizing similarly intensive, large-scale efforts in 2010 and 2020. Organizations like Everyday Democracy spread the lessons learned in Decatur to other cities. Decatur won the National Civic League’s prestigious All-America City Award in 2018 and 2023. It is a beautiful community, and officials in other cities may look at Decatur today and assume that it is an easy place to engage residents in democracy; in fact, Decatur became what it is today precisely because Abercrombie and his allies engaged their neighbors in democracy.

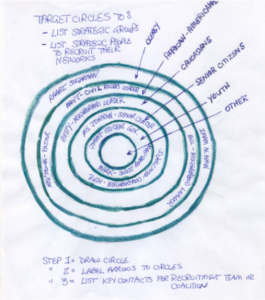

In addition to his organizing talents, Abercrombie was an accomplished artist, and he created graphical representations of some of the principles of public engagement. Tina Nabatchi and I used his depictions of recruitment funnels and community network maps (with Abercrombie’s permission) in the skills module that accompanied our textbook, Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy.

In addition to his organizing talents, Abercrombie was an accomplished artist, and he created graphical representations of some of the principles of public engagement. Tina Nabatchi and I used his depictions of recruitment funnels and community network maps (with Abercrombie’s permission) in the skills module that accompanied our textbook, Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy.

Abercrombie also invited people to contribute their own ideas to his picture: he would bring a big piece of newsprint with an outline of Decatur to community meetings, and invite people to add organizations, meeting places, neighborhood groups, and other civic assets to the map. It was participatory mapping, allowing the community to see itself and all its connections, long before civic tech made that concept cool.

Understanding the strength of those neighborly connections was a core part of Abercrombie’s genius. He believed that people should have a role in making serious public decisions and solving important public problems, but he knew that they would be more likely to participate, and would do a better job, if the experience was also friendly, gratifying, and fun. Abercrombie knew the power of art, music, food, and kids. He maintained that every city would be better off if it had a “Director of Dining, Drinking, and Dancing.”

Abercrombie was a leader who treasured the opportunity to nurture and support other leaders. Decatur won its 2023 All-America City Award on the basis of the city’s work to support youth development and leadership. I found myself interviewing a set of high school students on their experiences in the city; I told them how lucky they were to have grown up there. They looked at me and then one of them said, “Yes, Decatur is a great city! But it could be better…”

That statement would have been music to Abercrombie’s ears.