Democracy and citizenship continue to evolve, spurred by new threats and new opportunities. In order to exert some control over these changes, we need to understand the nature of the threats and how they developed, the shifts in how people are thinking about politics and community, and the democracy innovators and innovations that are emerging today. This series of essays, to be released weekly in advance of The Future of Citizenship: The 2023 Annual Conference on Citizenship, will help set the stage for a national discussion on where our country is headed.

By Matt Leighninger and Quixada Moore-Vissing

On all kinds of public issues, people want more choices, more information, and more of a say. In Taiwan, that general impulse found a specific outlet in 2014, after students and civic groups successfully shut down the government in protest of a pro-China trade agreement. In the aftermath of that upheaval, activists and government officials (including Audrey Tang, a civic hacker who became Taiwan’s first Digital Minister) began creating a process in which citizens could participate directly in decision-making. Over the next several years, the resulting “vTaiwan” platform has facilitated deliberation, voting, and lawmaking on issues such as the online sale of alcohol and the regulation of Uber.

The idea that citizens want chances to directly affect policy shouldn’t be surprising: all over the world, people now have myriad opportunities for self-expression and a massive array of options about what to buy, where to live, what to join, and how to connect. With so much power to choose in our private lives, is it any wonder that people want more direct forms of democracy in public life?

How governments respond to this impulse could have enormous impacts. As a whole, citizens have higher levels of education and much greater access to information than they did a generation ago, making them better able to contribute to public decision-making. But a number of other trends, from “fake news” to virtual reality, are making it more difficult for people to make sound judgements on important matters. In Taiwan and elsewhere, these conditions are raising new questions about the interactions between conscious and subconscious politics, and provoking innovators to create new combinations of thick and thin engagement.

Giving the people what they want

The official opportunities for more direct forms of democracy in the United States remain limited: 26 states allow ballot initiatives or referendums on specific policy proposals, but these are tied to regular election cycles and the process for placing an issue on the ballot requires a high degree of organization and political mobilization. In California, for example, initiatives require 365,000 signatures to qualify, and most of the issues that make it onto the ballot are ones that have been championed by wealthy individuals or advocacy groups that can afford to pay thousands of signature-gatherers. Ballot measures are often written in complicated language that voters find difficult to understand, they typically require a two-thirds majority to pass, and many legislatures have the legal capacity to modify or repeal them.

Despite these obstacles, the use of ballot measures is generally on the rise. In 2016, 71 made it to the ballot; in the 2022 election, there were 140.

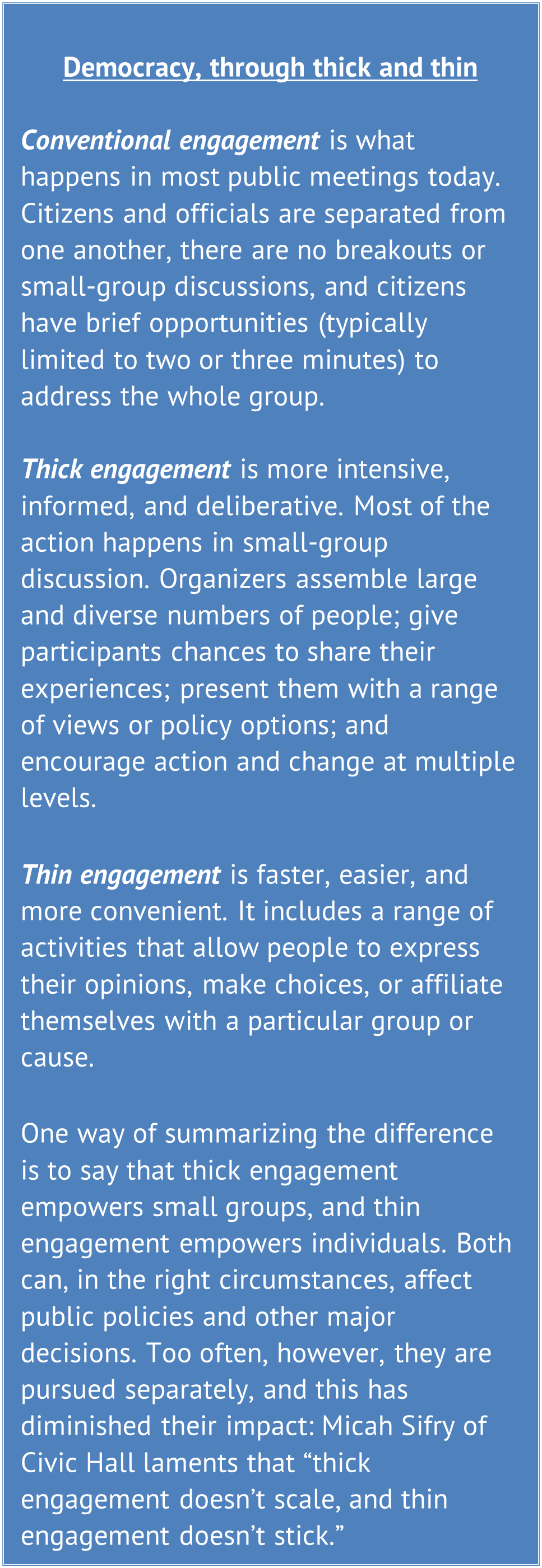

The increase in ballot measures is just one indicator of the desire for more opportunities for direct democracy. Another sign is the proliferation of formats for public engagement, from thick, deliberative processes to thin, viral social media campaigns. And some political candidates have seized on the desire of citizens for public agency: “increasing engagement” has become a common plank on campaign platforms. A candidate for Congress in San Diego made the centerpiece of his campaign a promise that he would put every major bill to a poll of his constituents; a candidate for city council in Boulder, Colorado, created an app for this function that he pledged to use if elected. Some local officials are persuaded to institute participatory budgeting because they feel it will help them get re-elected. In New York City, voters beat them to it in the 2018 election by passing a ballot measure to create a city-wide participatory budgeting (PB) process.

Manipulating Direct Democracy

The people who applaud direct democracy tend to be those who are frustrated by legislative gridlock, rancorous partisanship, and what they perceive as a general inability of government to make decisions and solve problems. Before 2016, the advocates of more direct forms of democracy seemed more numerous on the left side of the political spectrum than the right. But since the Brexit vote and the 2016 presidential election, many officials and activists on the left have become more wary of giving too much power to the people.

And while representative politics may be vulnerable to manipulation and domination by special interests, direct democracy also seems open to manipulation in a number of ways:

- Microtargeting. Observing the 2012 Obama presidential campaign, Peter Levine warned in 2013 that “In the era of digital networks, you can manipulate masses of people into doing what you want them to do by maintaining and exploiting a vast merged database of human activities, interconnections, and expressions.” Though progressives like the Obama campaign staff pioneered these methods, the rest of the world soon caught on, as Levine predicted. “Microtargeting is like using drones: it’s great if you’re the only one who has them…[we] must also consider whether these tools are a net benefit for democracy, and if not, what to do about that.”

- Fake news. A number of studies suggest that false information travels faster through social media than proven facts, not necessarily because it is incorrect but because it is unexpected and people are more likely to circulate things that surprise them. The number of people generating fake news may be small: David Lazer of Northeastern University reports that “there’s a small number of super-sharers – these are not bots, but they’re using automation to post large quantities. Only 0.1 percent – 1 in 1,000 – are responsible for 80 percent of the fake news on Twitter.”

- Virtual reality and “deep fakes.” Most fake news still takes the form of text – tweets or posts that relay inaccurate information. But increasingly, the social media landscape is now being infiltrated with incredibly realistic videos purporting to show officials, celebrities, and other public figures saying or doing things that are not real. These fictions tend to have a greater impact on citizens because video triggers emotions more than text.

- Question-answering bots. When citizens ask questions about public issues or services, the answers they get from officials, government departments, non-profit organizations, and advocacy groups are increasingly automated. Among their other uses, bots can interact with humans so realistically that people sometimes cannot tell they are talking with a machine pre-loaded with information.

Settings for using power wisely?

Many recent democratic innovations combine the opportunity to vote directly on policies with settings and methods that try to ensure those powers are used wisely. In Taiwan, the vTaiwan process relies on two strategies for informed deliberation. First, the online discussion occurs on a platform called pol.is, which allows citizens to make comments on policy proposals and vote on which comments they like best. It doesn’t allow people to reply directly to comments made by others; this seems to have limited trolling and vitriolic statements. Pol.is then uses artificial intelligence to code the votes and comments and draw a map showing the clusters of people’s preferences. As the map begins to show areas of agreement and disagreement, people begin drafting comments that will win votes from both sides and close the gaps. “The visualization is very, very helpful,” Tang said in an interview with MIT Technology Review. “If you show people the face of the crowd, and if you take away the reply button, then people stop wasting time on the divisive statements.”

Some of the discussion and comments occur in face-to-face deliberations that are open to the public. People who participate online are specifically invited to these meetings, at which the areas of agreement are further explored and refined so that they can be converted into legislation. Tang wants to add further innovations to the vTaiwan process, such as virtual reality, to help people visualize the options they are considering. “The goal is to make it enjoyable to participate in the deliberative process — like watching and acting in a 3D IMAX movie,” Tang writes.

Methods for merging direct and deliberative democracy have emerged in many other countries. PB is perhaps the most widespread example. Liquid democracy, which was pioneered by a German political party as a way to involve citizens in developing the party’s platform, is now being used in other countries. Finally, there are random-sample deliberative processes tied to ballot measures, such as the citizen’s initiative review (pioneered in Oregon), citizen’s juries (used in Minnesota and other states), and the citizen’s assembly (developed in British Columbia, Canada). In those examples, residents are chosen at random to participate in a thick, intensive engagement process in which they learn about a ballot measure and consider its pros and cons. The participants then provide information and sometimes recommendations to the voters.

These innovations provide different kinds of conscious engagement in an attempt to fulfill citizens’ desire to matter. However, some observers are not convinced that direct democracy – in any form – is the wave of the future. Civic technologist Abhi Nemani points out that “not enough people are actually voting” when they are given opportunities to weigh in directly on policy issues. He considers sentiment analysis and other methods of understanding citizen preferences – subconscious governance – to be a more powerful trend, calling it “indirect direct democracy.”

Others see subconscious and conscious engagement as complementary rather than competitive forces. Jaimie Boyd, Canada’s former Director for Open Government, argues that there are “greater opportunities for direct democracy than ever before,” because social media content analysis can “make decision-making much more inclusive.” In the national public consultations run by Boyd’s office, they conducted sentiment analysis, use thin engagement platforms like OpenText Magellan to gather input, and offered thicker forms of engagement for people who wanted to get more involved. It is a multichannel approach that tries to moderate the influence of any single avenue for engagement.

Deliberation without power, power without deliberation

Despite its successes, vTaiwan has been used mainly on technology-related policies, and not on issues of broader concern. Furthermore, while some of the vTaiwan conclusions have been enacted by the legislature, others have not. This follows a familiar pattern: democratic reforms that circulate information and support deliberation often conclude with non-binding referenda or recommendations that public officials are unwilling or unable to use. Methods of engagement that ask for public input and deliberation and then do not follow through on recognizing the public’s opinions may dissuade, rather than encourage, engagement.

Meanwhile, regular elections seem increasingly vulnerable to manipulations like micro-targeting and fake news. On many referenda, voters seem unprepared to weigh the consequences of the vote; immediately after the Brexit vote, websites explaining its potential consequences received huge numbers of hits, and many Britons expressed remorse at having voted “yes” on the initiative.

If the balance of decision-making power is in fact shifting toward citizens, there are many new reasons to be concerned about their capacity to make reasonable, informed choices – and many new ways to bolster that capacity. “Direct democracy hasn’t taken off as much in the U.S. as it has in Taiwan and elsewhere,” says tech and philanthropy expert Allison Fine. “But for better or worse, it is probably on the way.”

This essay is adapted from Rewiring Democracy, a publication of Public Agenda.