Democracy and citizenship continue to evolve, spurred by new threats and new opportunities. In order to exert some control over these changes, we need to understand the nature of the threats and how they developed, the shifts in how people are thinking about politics and community, and the democracy innovators and innovations that are emerging today. This series of essays, to be released weekly in advance of The Future of Citizenship: The 2023 Annual Conference on Citizenship, will help set the stage for a national discussion on where our country is headed.

By Nick Vlahos

Across the country, there are thousands of organizations working to protect, reform, strengthen, and champion American democracy. They are taking on a wide variety of roles, including: promoting patriotism and public service; providing information on public issues; advancing civic education; supporting voters; and establishing opportunities for people to help make decisions and solve public problems. But this ecosystem of healthy democracy networks, practitioners, and funders is incredibly diffuse. Those working in the space often lack a shared vision for the future, a collective understanding of resource availability and distribution, and a common definition of what efforts fall within the bounds of “healthy democracy” work.

To address these challenges, several longtime democracy researchers and practitioners joined forces to illuminate this growing, sprawling community of organizations, networks, and fields. At the 2023 Annual Conference on Citizenship, our team will present some data visualizations from a project called Mapping America’s Healthy Democracy Ecosystem.

The project has four goals:

- Help funders and investors take stock of the organizations, networks, and coalitions working to strengthen democracy;

- Help new organizations learn about existing organizations and efforts, and help existing organizations find potential opportunities for coordination and/or collaboration;

- Give practitioners more opportunities to share best practices, identify local efforts, and learn about current and potential sources of funding; and

- Provide a bird’s-eye view of the organizations, networks, and coalitions promoting healthy democracy and how the different fields, subfields, and sectors are supported and connected.

We are six months into the project, which will produce:

- Research by engaging with prominent practitioners in the field. This research will delve into the nuanced categorization of democracy work, exploring various issues and spaces where subject matter experts and funders are working to promote healthy democracy;

- A database of 10,000+ organizations categorized by different types and goals of democracy work. The database includes non-profit organizations, philanthropic funders, coalitions, academic programs, private companies, and other groups. Our team compiled and cultivated this list of organizations from a variety of formal and informal data sources, including existing field surveys, network membership rosters, expert references, and independent research. We are including local, state, and national organizations from across the political spectrum; and

- A website that houses a user-friendly searchable database of this healthy democracy ecosystem, along with visuals demonstrating the relationships among and between democracy organizations on multiple levels, including subject matter, finances, network affiliation, and geography.

See Appendix 1 for insights into how we categorize democracy organizations and the criteria guiding the inclusion of organizations in our map. At a minimum, healthy democracy work involves direct forms of interaction with the public that strive to promote positive relationships, communication, trust, and inclusion in diverse spheres of civic life. We exclude organizations whose missions are to promote violence, hate speech, and undermine basic human rights. Moreover, we recognize that democracy-strengthening organizations might not name the term democracy as part of their work – but they nonetheless still contribute to a healthy, inclusive, and vibrant democracy.

There are two specific lenses through which we are classifying and including organizations in our database and visualizations.

1. Top-Down, Expert-Driven

As the first step in the project, we held an in-person, full-day Strategy Session in April 2023 in Washington, DC, with 25 experts in the democracy field from relevant national organizations. We hosted an affinity mapping session to develop an initial set of ten categories to capture the main fields of democracy work in America. We then got feedback on this initial list over the course of 50 semi-structured interviews with additional subject matter experts. We presented the initial categories to interviewees to learn what was missing, whether they saw their own organizations in these categories, and then iterated the list based on what we heard. In addition, we are working from a quantitative approach to test these categories with other organizations and members of the public. For example, in collaboration with the Horizons Project and the 22nd Century Conference, we fielded questions about our healthy democracy categories, receiving 79 responses from diverse organizations.

Our top-down process involves interpreting and making meaning from our data by reworking the categories we developed with experts in the field.

One of the key lessons from this approach is that navigating the lexicon of democracy can be challenging. This is largely because people holding different political ideologies use different terms to describe their work and how they engage their constituents. Certain words can trigger and deter groups from wanting to engage with one another. However, the different terms and nomenclature that are being used to describe the work of different political ideologies often has overlapping, and in some cases have similar meanings regardless of the terminology being deployed. For example, “civic knowledge” focuses on instilling patriotic values by teaching American history using primary documents – whereas “civic education” means providing information and learning experiences to equip and empower citizens to participate in democratic processes. The former is primarily used by Conservatives, and the latter Progressives, but the work itself has many overlapping ideas, practices, and resources.

In an effort to make our list of 12 top-down democracy categories reflective of groups across the political spectrum, we have attempted to frame the categories of democracy work in a relatively neutral way that encompasses organizations from the left, center, and right. See Appendix 2 for more information about our classification process.

2. Bottom-Up, Organization-Centered

The top-down expert approach to categorizing democracy has the strength of crowdsourcing a wide variety of experiences of diverse leaders and thinkers. But we recognize that not every demographic and type of democracy organization could participate in our strategic session and in our interview and survey processes. Moreover, even within the existing top-down categories, the language is broad and may not fully encompass the specific language and nuances of how organizations describe themselves. Considering these factors, we developed a parallel process to categorize democracy organizations from the bottom-up.

We created our list of bottom-up tags by sifting through organizational websites and mission statements for identifying information. We manually tagged over 500 organizations before experimenting with AI (as noted below) to expand our scope.

Our bottom-up, organization-centered approach is an inductive, qualitative research process. Rather than have experts define how organizations are categorized, we turned to how organizations describe themselves within their mission statements and programmatic objectives. We also intend on inviting organizations we have not encountered to upload their information to be included in the database, as well as redefine how we’ve tagged their organization, using nuanced, precise words to reflect their aims, ambitions, and processes.

Both approaches involve degrees of subjective interpretation, but the bottom-up approach takes key terms directly from the source, i.e., the organization. In this way, we have been able to find interesting overlaps with our categories decided by experts, and yet significant differences between them. On the other hand, by grounding our categorization based on the organizations, we discover that the democracy ecosystem is vast and reflects work and terms beyond what the expert categorization process initially captured.

That said, having a larger list of democracy categories poses its own set of challenges, not least because a greater number of categories in democracy runs the risk of making it more difficult to visualize connections between organizations engaged in similar work. In addition, a bottom-up list means that categories of democracy work must always remain as a living, breathing set that will change depending on the new organizations being added, and where existing organizations are going.

Of course, there are significant overlaps between a top-down and bottom-up approach, and many of the types of organizations that have been categorized by the bottom-up approach will easily relate and overlap across many of the top-down categories. In any case, what becomes visible is that the field of democracy work can benefit from different types of methodological categorization, both top down and bottom up: trusted sources of leadership on the one hand, and straight from the sources/webpages of organizations on the other hand.

So far, we have identified 53 bottom-up categories. The list is not exhaustive as it continues to evolve just as we discover new organizations (see Appendix 2). In some instances, there is 1-to-1 alignment between the two sets of categories, but they also don’t necessarily coincide in several other cases, nor should they. But what both tables do at least offer is a contrast between a refined and an expansive view of how democracy organizations are being identified in our database and, consequently, within our visualizations.

Database and Visualization

We have over 10,000 organizations housed in an Airtable database with organizations coded by both top-down and bottom-up categories. The entries include each organization’s mission statement, website, network membership, location, presence(local/regional/national), and Form 990 financial information for the last several years. One challenge is that large amounts of data require more than a manual approach to inputting select information one-by-one. This is why we are experimenting with Generative AI to help us fill out our data set with any missing organizational information (e.g. website, location, mission statement, etc.) and help assign top-down and bottom-up categories. Nonetheless, we acknowledge there are shortcomings of using AI, and we continue to use human screening to counter potential inconsistencies.

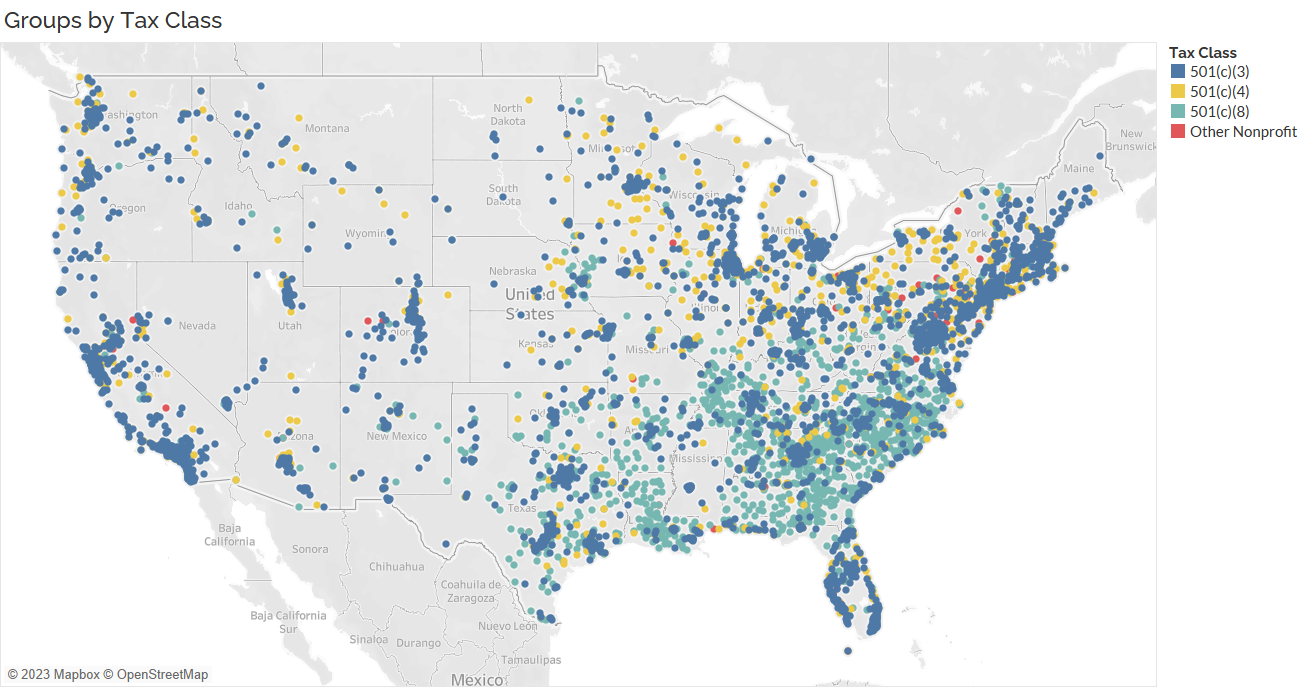

Our ecosystem will include visualizations based on geography, funding streams provided to different types of democracy work, as well as networks and coalitions. Below is a geographic visualization that maps all organizations within our database, using zip codes gathered from IRS tax filings. Users can zoom in to find local organizations as well as dive into local networks. Our database initially started with national organizations and in the next phase of this work we will continue to gather community level organizations, in addition to encouraging groups to add themselves.

Figure 1: Geographical Location of Organizations by Tax Class and Zip Code

Team

| Matt Leighninger | Carolyn Lukensmeyer | Rachel Fersh | Hala Harik Hayes | Nick Vlahos |