A new national survey finds that while many Americans feel left out of local decision-making and disconnected from their neighbors, they remain eager for better ways to participate. The findings reveal a mix of frustration, and hope about the state of civic life today.

The community survey is still live — take a few minutes to share your thoughts on local involvement and the civic innovation tools that could help make participation easier and more meaningful.

The survey, a collaboration between the National Civic League and ActiVote, a voter information and democracy app established in 2017, offers a snap shot of how residents experience and imagine civic participation today.

Responses ranged from approximately 700 to just over 900 per question. Results were weighted using ActiVote’s standard methodology, which contributed to their recognition as the eighth best pollster in the country for the 2024 election.

According to the survey, less than one in ten residents say they receive public information on time. Two-thirds believe that when decisions are made in their community, it’s “the usual suspects” who show up and dominate the process. And only 7% feel a strong sense of belonging where they live.

This mix of frustration and disconnection raises a key question: what might bring residents back in? Americans have clear ideas about how to strengthen democracy. They favor more opportunities for direct participation, such as ballot initiatives and online engagement tools; they also support citizen assemblies that bring diverse residents together to learn and make recommendations. Above all, they want to see public meetings redesigned to be more participatory, inclusive, and effective.

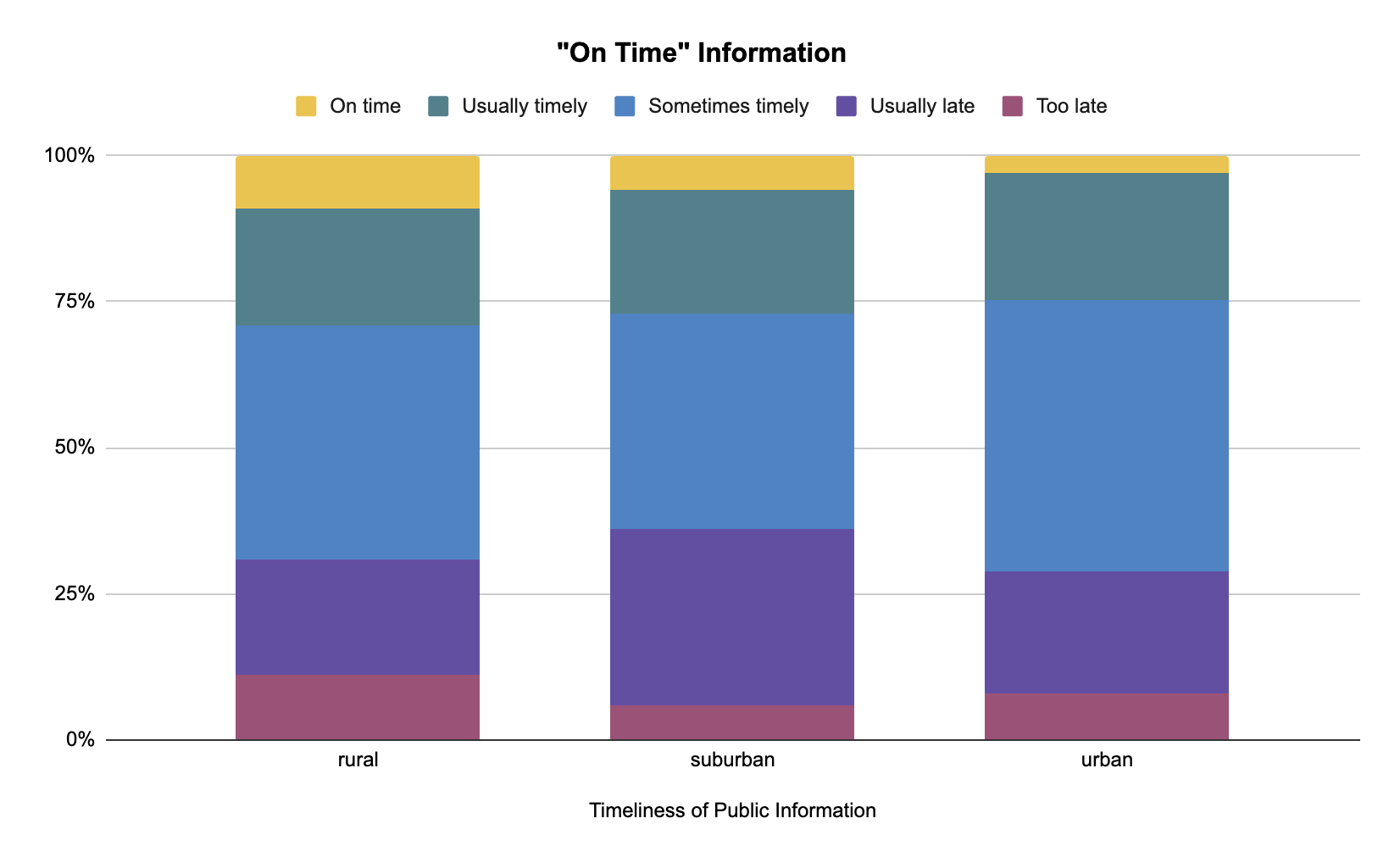

Public Information: Rarely On Time

Less than nine percent of people overall say they receive public information on time, a figure that cuts across rural, suburban, and urban communities. The sense of delay is widespread, but not felt equally everywhere.

Urban residents may have better access to information, with nearly half reporting that information is at least “sometimes timely.” By contrast, suburban respondents stood out for their frustration: more than a

Urban residents may have better access to information, with nearly half reporting that information is at least “sometimes timely.” By contrast, suburban respondents stood out for their frustration: more than a

third said information usually arrives late, and they reported the highest share of “too late” responses.

The findings show that while timeliness is a universal concern, better communication will be essential for restoring trust and drawing more people into civic life.

Decision-Making: The “Usual Suspects”

If delayed information leaves residents frustrated, decision-making leaves them feeling excluded. Sixty-five percent of respondents said community decisions are dominated by the ‘usual suspects,’ a view consistent across age, politics, education, income, and geography.

Confidence in broad participation is low. Only nine percent of respondents said their community usually or always has good turnout in decision-making, suggesting little faith in processes being open or representative. That sense of exclusion doesn’t end at the meeting table; it extends to how people feel about belonging in their communities.

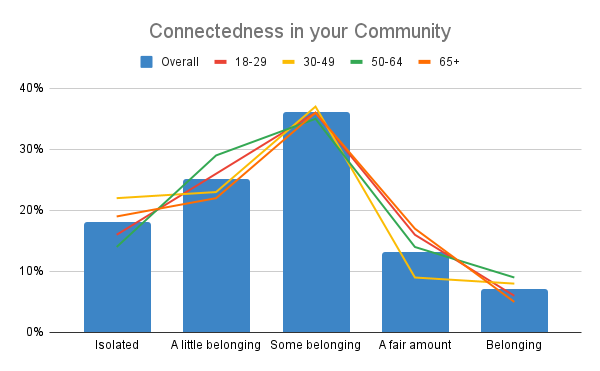

Connectedness: A Weak Sense of Belonging

Exclusion doesn’t only show up in processes. It also shapes how people feel about their community connections more broadly. Only seven percent say they feel a strong connection to where they live. By contrast, nearly half report feeling little or no connection at all, with 18 percent saying they feel isolated and another 25 percent describing only “a little belonging.”

Most fall in the middle, with 36 percent reporting ‘some belonging’ and 13 percent ‘a fair amount’ not fully disconnected, but not deeply rooted either.

The gaps are particularly clear by age. Older adults are somewhat more likely to report connection, while young adults stand out for their disconnection, with over one in five saying they feel isolated. Differences also appear across race and ethnicity. White respondents leaned toward “some belonging,” black respondents were more likely to say they felt only “a little belonging,” and Latino respondents were most likely to report a strong sense of belonging. Education plays a role as well, with college graduates somewhat more likely to feel connected than those with only a high school education.

Taken together with the findings on timeliness and decision-making, a pattern emerges. Fewer than one in ten say public information arrives on time, two-thirds say the same small group dominates decisions, and nearly half feel little or no belonging at all.

Barriers to Involvement

Even when residents want to take part in local decision-making, many feel unable to do so. Nearly half cited lack of time as the biggest barrier, and another 37 percent doubted that their involvement would make an impact — revealing both structural and trust-related challenges.

These barriers echo earlier findings: when information is late, decisions feel dominated, and belonging is weak, residents assume their voices won’t matter. The result is a participation paradox — people want a voice, but the system feels inaccessible, unimpactful, and closed off.

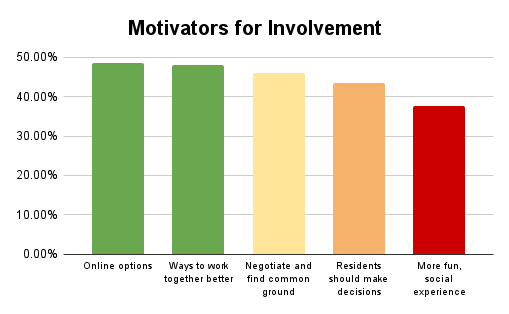

What Would Encourage Participation

Despite these barriers, residents are clear about what might draw them back in. Nearly half said they would be more likely

to get involved if leaders and residents could work together more directly. This reflects a desire for partnership and co-decision making, not just opportunities to comment on decisions already made. Another 48 percent pointed to digital options, underscoring the importance of lowering the barriers of time and logistics by making participation easier and more flexible.

Fewer people were motivated by the prospect of more enjoyable meetings with food, music, or social activities. Just 37 percent said those kinds of enhancements would make them more likely to participate. The lesson is that while enjoyable elements might help, the real motivators are substance and accessibility. Residents want engagement that matters and formats that fit into their lives.

Fewer people were motivated by the prospect of more enjoyable meetings with food, music, or social activities. Just 37 percent said those kinds of enhancements would make them more likely to participate. The lesson is that while enjoyable elements might help, the real motivators are substance and accessibility. Residents want engagement that matters and formats that fit into their lives.

New Civic Engagement Models

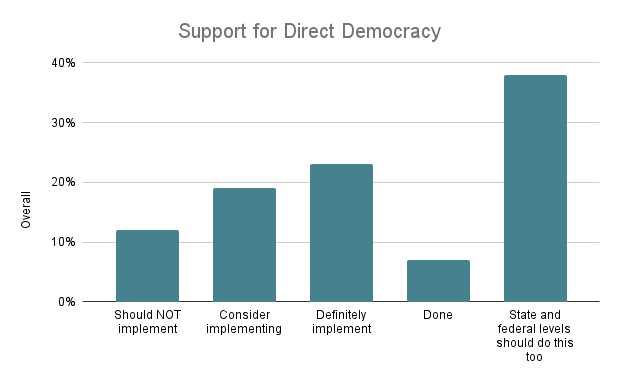

If residents feel shut out of current processes, they are also eager to reimagine how engagement might work. The survey revealed strong support for new and existing models of civic participation, though some stood out more than others.

Direct democracy, allowing residents to vote directly on policy issues, was one of the most popular ideas. (Only some states allow direct democracy via ballot initiatives and referenda; its use in local democracy varies dramatically. It is not a part of our federal governance model.) Sixty-one percent said they would like to see it implemented in some form, and enthusiasm was especially high among younger and lower-income respondents.

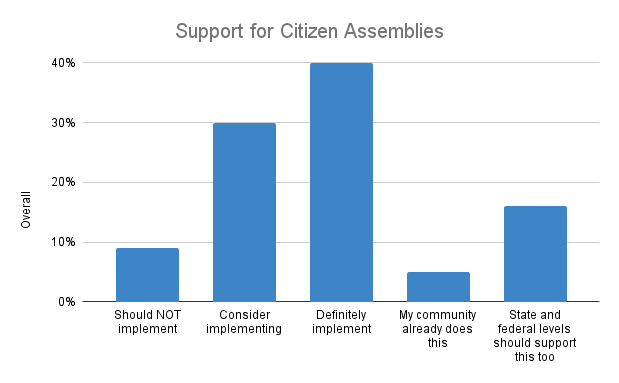

When asked about local governance structures, respondents expressed more enthusiasm for citizen assemblies than for neighborhood councils. Assemblies, which bring together a randomly-selected group of residents to deliberate on issues, earned support from 61 percent of respondents, compared with 48 percent for councils. The difference suggests that while neighborhood councils feel familiar, assemblies are viewed as a more innovative and inclusive approach, an alternative to the “usual suspects” dynamic that many say dominates decision-making today.

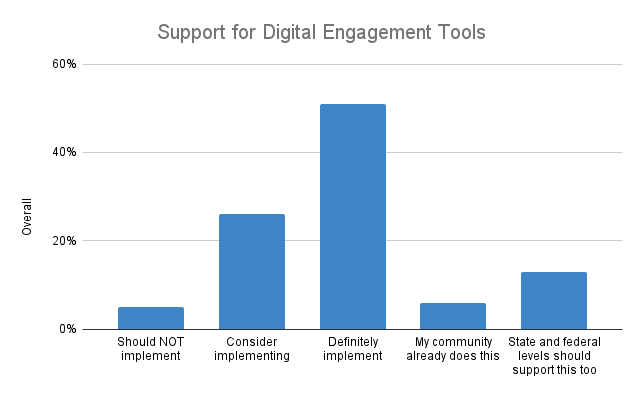

Two of the most widely supported ideas were digital participation tools and community survey panels. Roughly seven in ten respondents favored digital tools, and two-thirds supported survey panels—both with minimal opposition and broad bipartisan backing. These options cut across age, income, and education levels, making them among the most accessible and least polarizing reforms. Taken together, they show a clear appetite for engagement methods that are practical, flexible, and inclusive—tools that fit into busy lives and provide meaningful ways for residents to be heard.

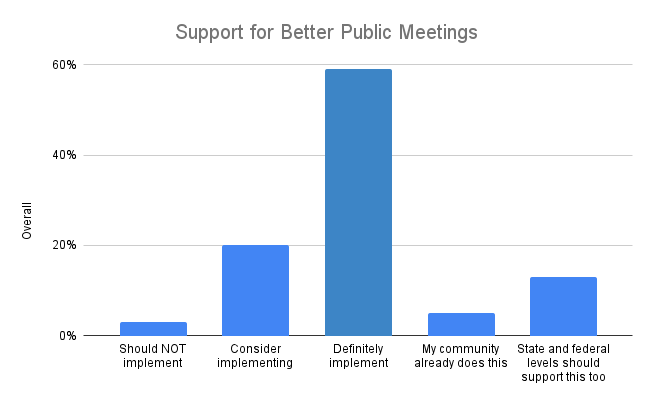

But the clearest message came from responses about public meetings themselves. More than three-quarters of respondents said meetings should be improved, making it the most widely supported reform of all those tested. Unlike abstract or experimental approaches, the demand for better meetings speaks directly to people’s lived experience. Meetings are where frustrations about timeliness, exclusivity, and impact converge and improving them is seen as the single most important step local governments can take.

Together, these results highlight a path forward. Residents are open to bold ideas like direct democracy and citizen assemblies, but they are especially eager for practical reforms that make participation easier, more accessible, and more impactful. Fixing the basics, timely information, inclusive meetings, opportunities for real collaboration, may be the surest way to rebuild trust and strengthen civic life.