By Alex Renirie

Another round of divisive national elections is hurtling too-quickly towards us, and it is more evident than ever that our democracy is in a crisis of imagination. Many of us are craving the kinds of stories that show a different path forward. Not a new candidate or plea for “civility” in national politics – but a wholly new design for democracy itself. One in which new leaders are motivated by solving problems, not holding on to power at all costs. And one that looks like the multiracial, multi-generational, gender-diverse, and culturally complex country we are.

When it’s hard to find hope on the national stage, it’s worth looking to examples of fundamentally grassroots democracies. Where are people cultivating new leaders from the ground up? Where are genuine instances of collaborative governance overriding adversarial bitterness? So often, these breakthroughs are happening at the local level. And last year, the City of Petaluma, California had one of those breakthroughs.

Governments around the world are experimenting with one such design for a different kind of democracy. Lottery-selected panels, often known as Citizens’ Assemblies, are a 50-year-old democratic innovation designed to counter rampant polarization and political elitism head-on. These panels transform both who participates in decision making and how decisions get made. With over 600 examples globally, the model is gaining traction as a way for governments to deeply engage their residents in collaborative, inclusive, and wise policy decisions.

While the U.S. was an early leader in the movement for lottery-selected democracy, we’ve been surpassed in recent decades by Europe, Asia, and Latin America. But one recent example shines new light on our potential for democracy innovation.

Last year, the 2022 Petaluma Fairgrounds Advisory Panel became the most intensive lottery-selected panel process convened in the U.S. to date. In a small city with agricultural roots just north of San Francisco, 36 Petalumans helped shape the fate of one of the city’s most beloved properties, which had been mired in decades-long conflict. My team at Healthy Democracy, a small nonpartisan nonprofit based in Oregon, led the design and facilitation of that process.

But before examining Petaluma’s story in greater depth, let’s imagine for another moment what it would look like not to innovate. Obviously, the consequences are as infinitely varied as the cities in which they occur. But a few things are nearly universal.

If We Don’t Act

It’s no secret that municipalities across the country are falling prey to the same bitter, adversarial politics that dominate our national political landscape. The types of conversations that once were safe havens for neighbor-to-neighbor collaboration (or at least tolerance) are fracturing, and the dominant cultural tendency towards polarization is slipping in through the cracks. If we don’t act, this trend will continue.

And of course, the voices who dominate public conversations at both the national and local levels continue to be disproportionately white, educated, male, and middle/upper class. My colleague Felipe Rey, founder of the democracy innovation lab iDeemos in Bogotá, Colombia, illustrates it best: imagine yourself giving a tour of our world to a time traveler from the 1800s. While most aspects of our daily lives would be wholly unrecognizable (the internet, sprawling cities, not to mention artificial intelligence!), one thing would be awfully familiar: our political systems. The kinds of people who held the most power in our democracy two centuries ago are still the ones many of our public forums are built for. And no surprise, it is they who benefit most. If we don’t act, the 2100s will look like this, too.

Moreover, many movements for building political power among marginalized communities have pivoted in recent years towards protecting basic voting rights and civil liberties. And while that work is vital to patching our fraying democratic institutions, we risk leaving too little energy for creatively reimagining the basic design of more inclusive and equitable governance. In this situation, many already underrepresented members of our communities find themselves too tired, under-resourced, or even intimidated to participate in the decisions that affect all of our day-to-day lives.

If we reframed democracy as a design challenge – like designing a great urban landscape or new technology – we might notice that our current public processes are veering dangerously off course.

The U.S. public recognizes this, too. In a 2020 Pew study, 62 percent of us said that the “fundamental design and structure” of the U.S. government needs “significant changes.”1 Ignoring this call will only fuel further cycles of disillusionment, disengagement, and cynicism.

A New Kind of Democracy

Rather than letting the dominant narrative of polarization and a disaffected populace take over, let’s give the people what they want – an overhaul of democracy’s design and structure.

Among the many democratic reforms lighting a new path, lottery-selected panels have a unique appeal as wholly reimagined systems that can bolster current democratic ecosystems.

While varied in terms of size, scope, and policymaking task, these panels always combine two core elements. First, they enlist a random group of community members that reflect the demographic profile of that place. Then, this microcosm of the public is given all the tools it needs to make a thoughtful decision – extensive information, a detailed process, and substantial time. Typically, participants in these processes achieve supermajority agreement on topics that elected officials couldn’t solve by themselves. And their detailed recommendations are adopted at unusually high rates.

This concept is not new; societies around the world have used lotteries to make decisions. Dating back to Medieval India and Ancient Athens, there are recorded histories of communities selecting policymaking bodies by lottery. In fact, randomness was sometimes seen as the only legitimate mode of selection; anyone with the personality to run for office was likely incentivized by ego. Randomness ensures that the people tasked with hard decisions are motivated to serve the common good – not just their own agenda.

Stakeholders and advocates then step in as advisors and information sources, whose purpose is to help panelists map the opinion landscape and identify thorny tradeoffs. Like a jury in the judicial system, panels are uniquely positioned to examine hot-button policy issues with independence and rigor. In the words of Petaluma’s City Manager, Peggy Flynn, the process is “the exact opposite of politics as usual.”

And in recent years, the modern versions of this model have taken off all over the world. A “deliberative wave”2 has crested – at the national level in France to identify climate solutions, as a state-level requirement in Victoria, Australia, for every comprehensive planning effort, and on numerous cultural and environmental topics across Brazil (just to name a few). In Paris, France and Bogotá, Colombia, lottery-selected bodies are becoming permanent fixtures of city-level governance. What if, one day, seeing everyday residents working alongside elected legislators was a core tenet of people-powered democracy?

To illustrate more fully how the process works, I will now dive deeply into the story of the Petaluma Fairgrounds Advisory Panel. The process was a highlight of my career and symbolizes an important steppingstone in the U.S. movement for deliberative democracy.

The Petaluma Fairgrounds Advisory Panel

Last year in Petaluma, the city’s leadership decided to take a bold step and try out this model on a hugely consequential local decision: the future of the valuable Sonoma-Marin Fairgrounds property, which had hosted its agricultural community, local businesses, schools, and myriad other community services for many decades. After being leased to a state fair agency for 50 years, a diverse group of residents had their first chance to reevaluate uses of the site and determine what would best serve the community as a whole.

Of course, future use of an extremely valuable city-owned property was not without its controversy. Planning for the site, mired in decades-long conflict, was at a crossroads. The city was facing growing community tension, which in many ways mirrored some of the hottest policy debates in California. How could the city meet the needs of its increasingly diverse and numerous residents while honoring the area’s rich agricultural roots? How could it preserve green space to increase climate resiliency and improve residents’ quality of life, while also addressing an out-of-control housing crisis? There was no consensus in sight.

After years of this increasing polarization, exacerbated by delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, local leaders knew that traditional engagement would only lead to more adversarial stalemates. And politics-as-usual risked continuous lack of representation among Petaluma’s BIPOC, youth, renter, and other marginalized populations.

In February 2022, the Petaluma City Council unanimously voted to try something new – and in doing so, established itself as a forerunner in the U.S. democracy innovation movement. They hired our organization, Healthy Democracy, to independently convene a panel of residents who would chart a new path forward.

Unlike typical advisory boards, this panel was made up of residents with no prior involvement with the property or with the city. They were selected by a process called a democratic lottery, in which a random cross-section of city residents was chosen to reflect predetermined demographic targets. The panel reflected the city’s demographics in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, age, educational attainment, geography, housing status, and experience of a disability. And selected panelists were provided with everything they needed to participate – stipends equivalent to a fair hourly wage, child and eldercare reimbursements, and comprehensive language services. To truly engage a representative sample of residents from all walks of life, we must actively mitigate the practical barriers that so many people face to participating in public life.

In this case, city leaders took innovation once step further by using equity-driven selection targets. Most democratic lotteries around the world establish selection targets based on equality – for instance, if 60 percent of a city’s population are renters, then renters will make up exactly 60 percent of the panel. But in this case, at the direction of Petaluma’s City Council, we over selected for more marginalized groups based on the rates they had been underrepresented in past City processes. For instance, renters were 34 percent of the Petaluma population but made up only 19 percent of past participants at events related to the General Plan update (which would include decisions related to the Fairgrounds). Therefore, their target on the Panel was adjusted up by that percentage point difference (15 percent), giving renters 49 percent of the 36 seats on the Panel. Equity-driven selection is just one way to ensure that our new democratic processes account for complex histories of exclusion in public policymaking.

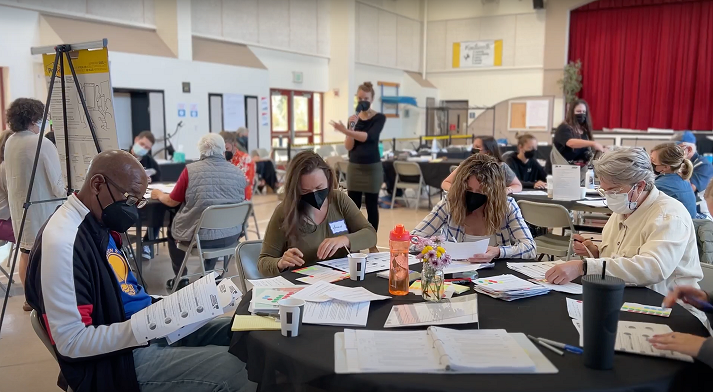

Panelists then met over five weekend sessions, examining many perspectives and policy proposals, before delivering their recommendations to the Petaluma City Council in the summer of 2022. Over the course of their 90 hours together, panelists were tasked with tackling an undeniably complex planning question. They heard from dozens of presenters on the topic, which were selected in part by an independent stakeholder committee and in part by panelists themselves. Panelists hosted a listening session with the broader community and reviewed surveys that collected ideas from the public. Based on their own Guiding Principles, prioritized criteria that should guide future planning on the site, the panel finally coalesced around three detailed visions for the property – including cross-cutting supermajority recommendations.

The process was guided by a team of professional moderators and took place mostly in rotating small groups. This allowed panelists themselves to fully own the process – taking over governance functions of the project and collaborating intensively to craft every word of their recommendations. While collaboration is an innate human drive, it often needs cultivating to overcome the forces of today’s political climate. In this process, panelists spent hours building their internal capacity for critical thinking, mitigating power imbalances in group settings, and practicing collaborative problem solving. This is more than some of our elected officials will ever receive on how to work together. And it made the Petaluma panelists incredibly capable stewards of this important decision. Since then, the group has remained involved in local decision making on this and other topics.

In the words of two Petaluma panelists:

“My experiences have been not only getting to know other Petalumans but getting to know and understand how democracy works or could work in a more functional way.” –Jared, panelist

“Being inclusive of all of our demographics and being able to sit and listen and appreciate what is needed for the community has been beneficial not just for me as a resident for 11 years in Petaluma but I think for the whole community.” – Mary, panelist

And it has become clear that the impact wasn’t only felt by panelists. The wider community saw value in the lottery-selected process at high rates. In a survey of the wider Petaluma community later conducted by a committee of panelists, over 74 percent of the 226 residents surveyed said they were aware of the panel’s work. And 52 percent said they thought the recommendations would have an impact on the final development of the fairgrounds.3

In the end, the panel’s supermajority recommendations were backed by broad community support. Even previously adversarial community members bought into the process and expressed appreciation to the panel for identifying win-win land use recommendations. In the words of former Petaluma Mayor, Teresa Barrett, “It has been a huge commitment, and it was a big leap into another way of working together… This process seems to move to collaboration from competition and I think that’s the only way we move forward.”

Getting “unstuck” and moving forward collaboratively is what so many of our local democracies need to thrive.

Where Next?

When it comes to planning our neighborhoods – let alone health care or foreign policy – we must practice a different way of doing democracy. We must not let our capacity for community decision making atrophy.

Lottery-selected democracy is no panacea, but it’s an example of complex design that directly counters many of the threats facing our democracy today. It guarantees representation of many identities rather than relying on those who have the time, confidence, and resources to show up. It fosters collaboration more concretely than one-directional community engagement. And it fundamentally shifts power to communities – by equipping residents with the forum, time, and tools to act as decision makers.

If our goal is to protect community-scale collaborative infrastructure, we need to rediscover and continuously improve creative tools for decision making. We can’t continue using the same methods hoping that new people will show up or a wholly new outcome will be achieved. And no one can be expected to upend our fractured systems without good processes that encourage us to do so.

At Healthy Democracy, we are deeply inspired by cities like Petaluma that are courageously experimenting with new democratic practices. The future of this model on the U.S. stage is ripe with possibility – who will innovate next?

Alex Renirie is Program Co-Director for Healthy Democracy.